Abstract

Some factors influencing the accuracy of the 30 % and SRSS rules commonly used to combine the effects of individual seismic components, are studied. For MDOF systems and earthquake loading the rules underestimate the axial load, but reasonably overestimate the shears. The rules are not always inaccurate in the estimation of the response for correlated components and totally uncorrelated (principal) components are not always related to an accurate estimation. The rules are not always associated to an inaccurate estimation for large values of the correlation of the individual effects (), and small values of ρ are not always associated to principal components and to an accurate estimation. Only for uncorrelated harmonic excitations and elastic behavior of SDOF systems, the individual effects are not correlated, and the rules properly estimate the combined response. It seems like that the rules were developed by using SDOF systems. Thus, the accuracy of the rules varies with the response parameter, the location of the structural element, the model of the structural system and the level of deformation. All these factors should be considered while estimating the combined response according to the rules.

1. Introduction

In routine simplified analyses, structural responses are estimated by applying each component one at a time and then their effects are combined in many different ways. The commonly used procedures are the 30 percent (30 %) and the Square Root of Summation Squares (SRSS) combination rules. Many codes around the world like International Building Code [1] and The México City Code [2] consider these combination rules. The codes, however, do not explicitly state the applicability of these rules: it is not specified the type of structures (simple or complex systems) to be considered or if the rules can be applied to both, elastic and inelastic behavior. It is not specified either if the individual responses produced by each component should be collinear or non-collinear.

The ways of combining the individual effects of the seismic components have been a topic of interest to the civil engineering profession. Penzien and Watabe [3] stated that the three components of an earthquake are uncorrelated along a set of axes generally denoted as principal axes. Rosenblueth [4] stated “lack of correlation of the principal accelerograms insures that responses are also uncorrelated”. Smeby and Der Kiureghian [5] observed that, for response spectra analysis of linear structures, when the two horizontal principal components are not along the structural principal axes, the effect of correlation is small. Newmark [6] and Rosenblueth and Contreras [7] proposed the Percentage Rule to approximate the combined response as the sum of the 100 % of the response resulting from one component and some percentage () of the responses resulting from the other two components. To combine the two horizontal components, Newmark [6] and Rosenblueth and Contreras [7] suggested to be 40 % and 30 %, respectively. Many other studies can be found in the literature [8-10]; however, most of them were limited to elastic analysis applied to single degree of freedom (SDOF) systems or to simplified plane concrete frames with a few stories connected by rigid diaphragms. They did not consider the inelastic behavior of the structural elements existing in actual 3D structural systems and the appropriate energy dissipation mechanisms. In another investigations, Reyes-Salazar et al. [11, 12], by using nonlinear time history analysis of complex multi-degree of freedom (MDOF) systems, observed that both the 30 % and the SRSS rules could underestimate the combined response and that the energy dissipation mechanisms should be considered as accurately as possible. However, realistic structural systems, the effect of correlation of the earthquake components on the accuracy of the rules, were not considered in these studies.

The specific issues addressed in this study are: a) to estimate the accuracy of the commonly used combination rules for complex MDOF systems for elastic and inelastic behavior and for collinear an non-collinear response parameters and b) the accuracy of the rules for simplified systems and loading condition.

2. Methodology

2.1. Structural models

The 3- and 9- story buildings considered in the SAC steel project [13], are used in this study to address the issues raised earlier. They will be denoted hereafter as Models 1 and 2, respectively. The beams and columns sections are given in Table 1. Additional information for the models can be obtained from the report [13]. In this study, the steel buildings are modeled as complex MDOF systems. The accuracy of the rules is also studied for equivalent SDOF systems. One equivalent SDOF model is considered for each steel building. They will be denoted hereafter as Model 1E and Model 2E. The natural period, damping ratio and the yielding strength are selected to be the same for the SAC and the equivalent SDOF models.

Table 1Beam and columns sections for the SAC models

Model | Moment resisting frames | Gravity frames | |||||

Story | Columns | Girders | Columns | Beams | |||

Exterior | Interior | Below penthouse | Others | ||||

1 | 1\2 | w14x257 | w14x311 | w33x118 | w33x118 | w14x68 | w18x35 |

2\3 | w14x257 | w14x312 | w30x116 | w30x116 | w14x68 | w18x35 | |

3\roof | w14x257 | w14x313 | w24x68 | w24x68 | w14x68 | w16x26 | |

2 | –1 | w14x370 | w14x500 | w36x160 | w36x160 | w14x193 | w18x44 |

42737 | w14x370 | w14x500 | w36x160 | w36x160 | w14x193 | w18x35 | |

42769 | w14x370 | w14x500 w14x455 | w36x160 | w36x160 | w14x193 w14x145 | w18x35 | |

42798 | w14x370 | w14x455 | w36x135 | w36x135 | w14x145 | w18x35 | |

42830 | w14x370 w14x283 | w14x455 w14x370 | w36x135 | w36x135 | w14x145 w14x109 | w18x35 | |

42861 | w14x283 | w14x370 | w36x135 | w36x135 | w14x109 | w18x35 | |

42893 | w14x283 w14x257 | w14x370 w14x283 | w36x135 | w36x135 | w14x109 w14x82 | w18x35 | |

42924 | w14x257 | w14x283 | w30x99 | w30x99 | w14x82 | w18x35 | |

42956 | w14x257 w14x233 | w14x283 w14x257 | w27x84 | w27x84 | w14x82 w14x48 | w18x35 | |

9/roof | w14x233 | w14x257 | w24x68 | w24x68 | w14x48 | w16x26 | |

2.2. Earthquake loading

To study the responses of the models comprehensively and to make meaningful conclusions, they are excited by twenty recorded earthquake motions in time domain with different frequency contents, recorded at the following stations: Fun Valley, Reservoir 361; Convict Creek; Cerro Prieto; Parkfield, Joaquin Canyon; Olympia Hwy Test Lab; Utilities Bldg, Long Beach; El centro, California; Centerville Beach, Naval Facility; Gilroy Array Sta No 4; Olympia Hwy Test Lab; Castaic-Old Ridge Route; Long Valley Dam; El Centro-Imp Vall Dist; Palo Alto; UCSB Goleta FF; Parkfield Fault Zone 14; Chihuahua; Canoga Park, Santa Susana; Ferndale, California; Indio, Jackson Road. The predominant periods of the earthquakes vary from 0.11 to 0.66 sec. The earthquake time histories were obtained from the Data Sets of the National Strong Motion Program (NSMP) of the United States Geological Surveys (USGS).

2.3. Loading cases

In order to meet the objectives of the study, several seismic and harmonic load cases need to be considered. Recorded horizontal time histories will be denoted as normal components. When they are transformed to uncorrelated components following the procedure suggested by Penzien and Watabe (1975) they will be denoted as principal components. The symbols and will indicate that the structures are excited by the normal components, and and will indicate that the principal components are used instead. Hence, the notation (, ) indicates that the structure is excited by the first and second normal components applied simultaneously to the N-S and E-W directions of the structure, respectively. Similarly, the notation (0, ) indicates that the structure is excited by only the first principal component acting along the E-W direction. The following particular load cases are considered:

Case 1: (, ); Case 2: (, ); Case 3a: (, 0); Case 3b: (0, ); Case 4a: (, 0) and Case 4b: (0, ). Similarly, another four cases of analysis are considered when the principal components are applied, they are Case 5: (, ); Case 6: (, ); Case 7a: (, 0); Case 7b: (0, ); Case 8a: (, 0) and Case 8b: (0, ). Thus, for two structures, twenty earthquakes, eight cases, and considering the responses to be elastic and inelastic, a total of 640 analyses of complex MDOF structures under seismic loading are required. For any response parameter (axial loads or base shear), the reference response for normal components, denoted hereafter as , is considered to be the maximum response of Cases 1 and 2. Similarly, the reference response for the principal components, , is considered to be the maximum response of Cases 5 and 6.

3. Accuracy of the rules for MDOF systems and Earthquake loading

3.1. Accuracy of the rules

According to loading Case 3 and the 30 % combination rule, two possible combined responses can be calculated for normal components; they are and , where and are defined as the responses produced for Cases 3a and 3b, respectively. The larger of the two combined responses when normalized with respect to the reference response () defined earlier will give a random variable defined as . Following exactly the same procedure for Load Case 4, can be calculated. The combination of both cases ( and ) and 20 earthquakes give a total of 40 sample points, which will be denoted by the random variable . Considering principal components and excitations given by load Cases 7 and 8, 40 sample points are similarly generated, it will be denoted as the random variable . Plots for the and parameters for each earthquake are developed, but are not shown, only the fundamental statistics are given below. The statistics of and are summarized in Columns 3 through 6 of Table 2. The results clearly indicate that, for the case of axial load, on an average basis, the 30 % combination rule underestimates the combined axial load by about 10 % and that the uncertainty associated with the estimation is too large in some cases. However, for base shear, unlike the case of axial load, both rules reasonably overestimate the combined response, the overestimation is about 10 %. The uncertainty in the estimation is much larger for axial load than for base shear. The observations made for the normal components are essentially identical to that of principal components. It should be noted that interior and exterior columns oriented in the north and south direction of the perimeter frames were considered.

Normalized response parameter similar to those of the 30 % rule are also estimated the SRSS rule. The corresponding random variables are denoted as and for normal and principal components, respectively. The statistics are summarized in columns 7 through 10 of Table 2. The major observations made for the 30 % rule for axial loads and base shear also apply to this rule. These results indicate that for complex MDOF systems, there is a certain degree of correlation between the effects of individual components of earthquakes, even for the case of uncorrelated components. Statistic similar to those of elastic behavior are also developed for inelastic behavior but are not shown. All the observation made for elastic behavior essentially remain the same for inelastic behavior. The only additional observation is that the uncertainty in the prediction significantly increases for axial load.

Table 2Statistics for Rn,30, Rp,30, Rn,SRSS and Rp,SRSS for MDOF systems and earthquake loading, axial load and interstory shear, elastic behavior

Model | Location | 30 % rule | SRSS rule | Sample size | |||||||

Normal | Principal | Normal | Principal | ||||||||

Mean | COV | Mean | COV | Mean | COV | Mean | COV | ||||

1 | Axial load | INT-NS | 0.89 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 0.16 | 0.87 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 0.15 | 40 |

EXT-NS | 0.87 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.22 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 0.83 | 0.20 | 40 | ||

GRAV | 1.00 | 0.16 | 1.02 | 0.14 | 1.01 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 40 | ||

INT-EW | 0.92 | 0.16 | 0.93 | 0.17 | 0.85 | 0.17 | 0.93 | 0.17 | 40 | ||

EXT-EW | 0.89 | 0.23 | 0.86 | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.21 | 0.85 | 0.20 | 40 | ||

ALL | 0.91 | 0.19 | 0.91 | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 200 | ||

Shear | ST3 | 1.12 | 0.07 | 1.08 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.09 | 1.10 | 0.08 | 40 | |

ST2 | 1.12 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.08 | 1.14 | 0.10 | 1.12 | 0.08 | 40 | ||

BASE | 1.10 | 0.09 | 1.10 | 0.07 | 1.12 | 0.10 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 40 | ||

ALL | 1.12 | 0.08 | 1.09 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.10 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 120 | ||

2 | Axial load | INT-NS | 0.91 | 0.15 | 0.88 | 0.22 | 0.89 | 0.13 | 0.87 | 0.22 | 40 |

EXT-NS | 0.87 | 0.14 | 0.84 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.14 | 0.88 | 0.09 | 40 | ||

GRAV | 1.01 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 0.10 | 40 | ||

INT-EW | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.87 | 0.23 | 0.85 | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0.24 | 40 | ||

EXT-EW | 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 0.10 | 40 | ||

ALL | 0.90 | 0.14 | 0.90 | 0.16 | 0.89 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 0.16 | 200 | ||

Shear | ST10 | 1.12 | 0.06 | 1.08 | 0.07 | 1.12 | 0.08 | 1.09 | 0.05 | 40 | |

ST9 | 1.12 | 0.05 | 1.09 | 0.07 | 1.13 | 0.07 | 1.09 | 0.06 | 40 | ||

ST8 | 1.13 | 0.05 | 1.09 | 0.07 | 1.13 | 0.07 | 1.09 | 0.06 | 40 | ||

ST7 | 1.12 | 0.06 | 1.09 | 0.07 | 1.13 | 0.07 | 1.09 | 0.06 | 40 | ||

ST6 | 1.12 | 0.07 | 1.10 | 0.06 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.05 | 40 | ||

ST5 | 1.11 | 0.07 | 1.10 | 0.06 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.07 | 40 | ||

ST4 | 1.12 | 0.07 | 1.11 | 0.06 | 1.15 | 0.09 | 1.10 | 0.07 | 40 | ||

ST3 | 1.13 | 0.07 | 1.12 | 0.05 | 1.15 | 0.09 | 1.11 | 0.07 | 40 | ||

BASE | 1.14 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.05 | 1.16 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 0.06 | 40 | ||

ALL | 1.12 | 0.06 | 1.10 | 0.06 | 1.14 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.06 | 360 | ||

3.2. Correlation between individual effects

The basic assumption of the SRSS rule is that there is no correlation between the horizontal components. It is implicitly assumed that if there is no correlation between the accelerograms, the corresponding effects will also be uncorrelated. The degree of correlation between the individual effects of the horizontal components and the effect of correlation on the accuracy of the rules are now discussed. The correlation coefficients () are estimated for Models 1 and 2, for normal and principal components, for elastic and inelastic behavior and for collinear (axial load) and non-collinear (base shear) response parameters. However, the results are not given, they are only conceptually discussed. It is found that normally recorded components may be highly correlated and that the ρ valuessignificantly vary from one earthquake to another and from one element to another. Most of the values can be considered negligible (smaller than 0.25). For many cases however, the correlation is significant. Values of larger than 0.5 are observed in many cases. It is observed that the rules are not always inaccurate in the estimation of the combined response for large values of . On the other hand, small values of the coefficients are not always related to an accurate estimation of combined response. The implication of this is that there may be other factors that influence the accuracy of the combination rules.

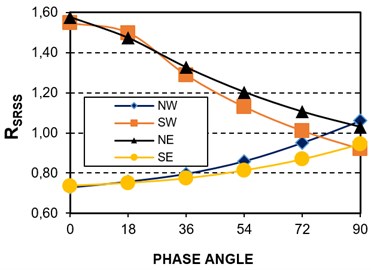

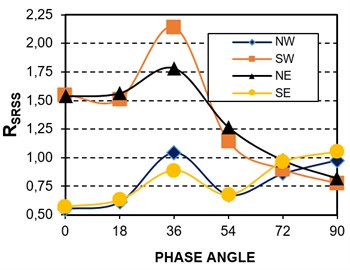

4. Accuracy of the rules for SDOF systems and harmonic loading

The accuracy of the rules and the correlation coefficients for the equivalent SDOF systems subjected to horizontal harmonic acceleration of the base is now discussed. The and parameters are used for this purpose. They are essentially the same as and , but now harmonic loading is used instead. As for the case of MDOF systems and earthquake loading, results for axial load and base shear, elastic and inelastic behavior and Models 1E and 2E were obtained. Typical valued of for the axial loads on columns of Model 1E are presented in Figs. 1(a) and 1(b) for elastic and inelastic behavior, respectively. In the horizontal axes the phase angle between the horizontal components is considered. It is shown from the results that for elastic SDOF systems and harmonic loading, the 30 % and SRSS rules may underestimate or overestimate the combined axial load for correlated components. For uncorrelated components, the rules accurately estimate the elastic axial load. However, for inelastic behavior, the rules may underestimate or overestimate the combined axial load even for uncorrelated components. The combined base shear is reasonably overestimated practically in all the cases. Thus, the level of underestimation or overestimation of the rules vary with the level of correlation of the components, the type of response parameter, the location of the structural member under consideration and the level of structural deformation.

Fig. 3Accuracy of the SRSS rule for SDOF systems and harmonic loading, Model 1E

a) parameter, elastic behavior

b) parameter, inelastic behavior

5. Conclusions

Some factors influencing the accuracy of the commonly used 30 % and SRSS combination rules to combine the effects of individual seismic components are studied and, on light of the results, the accuracy of these rules as well as the influence of the correlation of the components and the correlation of the individual effects () on the accuracy are calculated. The accuracy of the rules is also estimated for equivalent SDOF systems and harmonic loading. Results indicate that for MDOF systems and earthquake loading the rules underestimate the axial load, but reasonably overestimate the shears. The rules are not always inaccurate in the estimation of the response for correlated components and totally uncorrelated (principal) components are not always related to an accurate estimation. The rules are not always associated to an inaccurate estimation for large values of , and small values of are not always associated to principal components and to an accurate estimation. For SDOF systems, elastic behavior and highly correlated harmonic components, both rules may underestimate or overestimate the axial load depending on the location of the structural element under consideration, while for components with low correlation, both rules properly estimate the axial load; for inelastic behavior, the rules may underestimate the axial load even for uncorrelated components, indicating that the elastic response of structures subjected to dynamic loading may be quite different than that of the inelastic response. Only for uncorrelated harmonic excitations and elastic behavior of SDOF systems, the individual effects are not correlated, and the rules properly estimate the combined response. It seems like that the rules were developed by using SDOF systems. Thus, the accuracy of the rules varies with the response parameter, the location of the structural element, the model of the structural system and the level of deformation. All these factors should be considered while estimating the combined response according to the mentioned rules.

References

-

International Building Code (IBC). International Code Council, Falls Church, VA, 1993.

-

Normas Técnicas Complementarias de Diseño por Sismo. Reglamento de Construcciones del Distrito Federal, Gaceta Oficial del Distrito Federal, México City, 2004.

-

Penzien J., Watabe M. Characteristics of 3-dimensional earthquake ground motions. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics, Vol. 3, 1975, p. 365-373.

-

Rosenblueth E. Design of Earthquake Resistance Structures. Pentech Press Ltd., 1980.

-

Smeby W., Der Kiureghian A. Modal combination rules for multi-component earthquake excitation. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics, Vol. 13, 1980, p. 1-12.

-

Newmark N. M. Seismic design criteria for structures and facilities, Trans-Alaska pipeline system. Proceedings of the U.S. National Conference on Earthquake Engineering, 1975, p. 94-103.

-

Rosenblueth E., Contreras H. Approximate design for multi-component earthquakes. Journal of Engineering Mechanics Division ASCE, Vol. 103, 1977, p. 895-911.

-

Bisadi V., Head M. Evaluation of combination rules for orthogonal seismic demands in nonlinear time history analysis of bridges. Journal of Bridge Engineering, Vol. 16, Issue 6, 2011, p. 711-717.

-

Mackie K. R., Cronin K. J. Response sensitivity of highways bridges to randomly oriented multi-component earthquake excitation. Journal of Earthquake Engineering, Vol. 15, Issue 6, 2011, p. 850-876.

-

Tsourekas A., Athanatopoulou A. Evaluation of existing combination rules for the effects caused by three spatial components of an earthquakes. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, Vol. 17, Issue 7, 2013, p. 1728-1739.

-

Reyes-Salazar A., Juarez-Duarte J. A., López-Barraza A., Velázquez-Dimas J. I. Combined effect of the horizontal components of earthquakes for moment resisting steel frames. Steel and Composite Structures an International Journal, Vol. 4, Issue 3, 2004, p. 189-209.

-

Reyes-Salazar A., López-Barraza A., López-López L. A., Haldar A. Multiple-components seismic response analysis – a critical review. Journal of Earthquake Engineering, Vol. 12, Issue 5, 2008, p. 779-799.

-

State of the Art Report on Systems Performance of Steel Moment Frames Subjected to Earthquake Ground Shaking. SAC Steel Project, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Report FEMA 355C, 2000.

Cited by

About this article

This paper is based on work supported by La Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa (UAS) under Grant PROFAPI-2012/148. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors.