Abstract

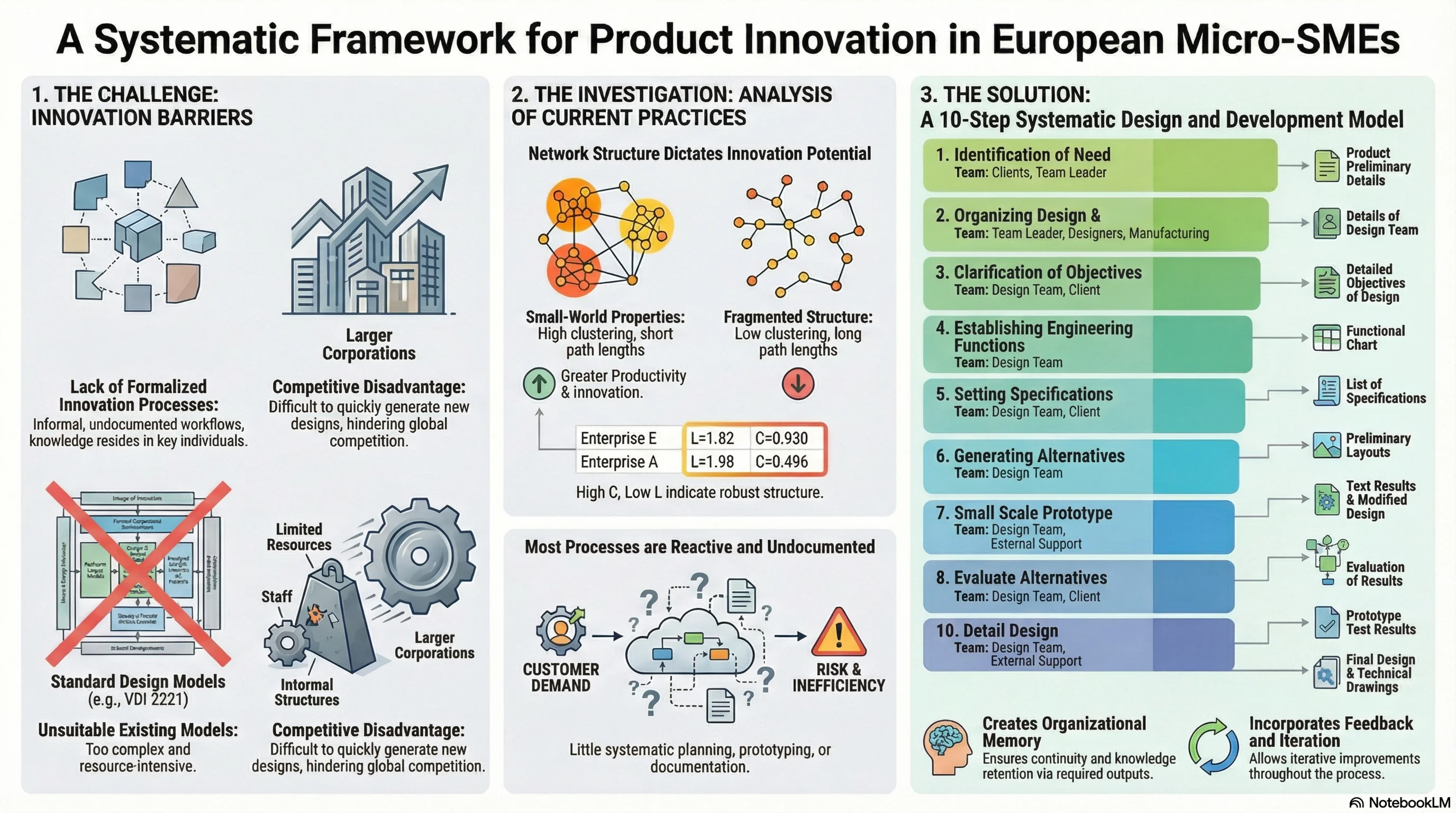

A methodical approach is created in this study to aid SMEs across Europe (Turkiye, UK, Belgium, Italy) in their product and process development endeavors. Methods and processes that must be followed are examined and streamlined, starting from the point of client contact, and ending with establishment of a pilot production line. This study provides strategies to help technicians and engineers create excellent product designs. Though most of the concepts and methods it will produce are anticipated to be applicable to the design of all types of goods, its primary focus is on the engineering-related aspects of product design. The formulation of problems and the conceptual and embodiment phases of design are the main topics of this work. It will support designers in SMEs with problem identification, explanation, and generation and assessment of solutions. To understand their approach and issues, a thorough search in this field is conducted, along with interviews with multiple SMEs. Additionally, to ascertain the SMEs’ network architecture and how their technical employees interact inside these organizations in a way that supports the creation of new products. This will demonstrate these SMEs' advantages or strengthen their creative positions in the face of global competition.

Highlights

- Micro-scale industrial enterprises often lack formalized design processes and documented workflows, which significantly hinders their innovation capacity and competitive resilience compared to large-scale corporations.

- Analysis shows that "small-world" network structures, marked by high clustering and short path lengths, correlate with higher productivity and stronger innovation capacity in micro-enterprises across Europe.

- A novel 10-step systematic framework tailored for micro-SMEs streamlines product development and builds "organizational memory" through documentation, ensuring business continuity during personnel changes.

1. Introduction

The development of novel products and production processes represents both an indispensable and rewarding undertaking for ensuring the sustainability of competitive enterprises. Rapid technological advancement, the proliferation of computer-based applications, and improved communication capabilities collectively facilitate the introduction of products within markedly shortened timeframes. Although large-scale corporations have successfully adopted concurrent engineering practices to expedite product development, micro and certain small-scale industrial enterprises face persistent difficulties in generating new designs or modifying existing products under compressed cycles, thereby limiting their ability to compete with larger counterparts in the sector.

The aim of this research is to develop a systematic framework that enables accelerated and strategically oriented product and process design and development tailored to micro-scale industrial enterprises, while simultaneously examining the organizational network structures of individuals employed in such firms across Europe (Turkey, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and Italy). Spanning from the conceptual design stage to the establishment of a pilot production line, the requisite processes and techniques will be examined and refined. The proposed framework is intended to enable micro-scale firms to implement innovative design strategies more rapidly and efficiently.

While extensive research exists on product development methodologies and network structures for small, medium, and large enterprises, there is a significant lack of tailored systematic frameworks for micro-scale industrial enterprises (those with fewer than 10 employees). These enterprises often lack formalized design processes, documented workflows, and structured internal or external networks, which hinders their innovation capacity and competitive resilience. Existing models (e.g. VDI 2221, concurrent engineering) are not directly applicable due to resource constraints, limited technical staff, and informal organizational structures. Moreover, although the benefits of small-world network structures are well-documented for larger firms, their applicability and impact on micro-enterprises remain underexplored.

SMEs constitute a fundamental component of both the economic structure and the social fabric of a country. However, most of the existing research relies on proxy indicators of performance and examines rather broad determinants influencing SME outcomes [1].

Micro-scale industrial enterprises face an urgent necessity to develop systematic product and process development approaches to compete more effectively with large-scale corporations in global markets. This manuscript aims to support micro-scale firms in enhancing their organizational structures so that they can strategically adapt to rapidly advancing technologies. Furthermore, the study intends to implement a form of technological auditing, through which information concerning firms’ strategies for new product development, their learning mechanisms, innovative frameworks, internal and external linkages, and developmental processes will be systematically gathered. Such an audit will emphasize the knowledge, competencies, and expertise that differentiate a firm from its competitors and enable it to attain strategic objectives. The influence of this auditing process on firms’ innovation performance is assessed, as well as the feasibility of its application. Previous investigations within the manufacturing sector demonstrate that fewer than 10 % of firms have acquired substantial capabilities in innovative product and process development by leveraging emerging technologies. This finding suggests that only a limited proportion of firms secure a position among global industry leaders with respect to the advancement of novel technologies, products, and processes, underscoring the competitive gap faced by smaller enterprises [2], [3].

1.1. Review of existing design methods

Although the discrete phases of design have typically been examined in isolation, accounts of the overall process, particularly regarding the complex interplay of creativity, analysis, experimentation, evaluation, and related elements provide a compelling vantage point for understanding its dynamics. Consequently, design research and strategies for enhancing design are partitioned in a manner comparable to diagrams of the design process, which divide the activity into blocks representing its distinct phases or dimensions [4].

The advancement of design activities is primarily guided by heuristic knowledge, drawing upon prior experience and commonly accepted rules of thumb, though such approaches provide no definitive guarantee of success. Various models have been proposed to conceptualize the design process. According to Cross [5], the fundamental stages of design comprise four key steps: exploration, generation, evaluation, and communication. Another model, proposed by Crilly, has four stages: problem analysis, conceptual design, scheme embodiment, and detailing. “Problem analysis” is comparable to the “exploration” stage of the model in question [6].

Six steps more comprehensive prescriptive model: programming, data collection, analysis-synthesis, development, and communication. There are three stages: the executive, creative, and analytical phases [7]. Some rather complex models have been offered in the literature, but they usually tend to obscure the main activities by directing too much attention on numerous details and tasks [8]. Pahl and Beitz, on the other hand, propose a reasonably comprehensive model that integrates multiple steps [9]. Similarly, Hubka introduces a highly detailed model [10], in which the design process is decomposed into clearly identifiable stages to achieve near-optimal solutions in the most cost-effective manner.

The VDI, the German association of professional engineers, issues numerous directives in this domain. Among them is Systematic Approach to the Design of Technical Systems and Products (VDI 2221). This document promotes a structured, transparent, and rational methodology that remains independent of any specific industrial sector. The framework incorporates seven phases: defining and clarifying the assignment, determining functions and their interrelations, exploring solution concepts and their combinations, decomposing the problem into feasible modules, generating layouts for essential modules, finalizing the comprehensive layout, and formulating production as well as operational guidelines.

By addressing administrative, technical, and financial considerations during the early stages, Levitt introduced the concept of total design [11]. His framework aimed to guide the entire product development process by offering a structured orientation. Within this model, the design core is constrained by the product specifications derived from the overall design activity plan. Emphasizing the solution-oriented character of design, Conceptualizing the design process is only evaluative and analytical forms of design activity are compatible with inductive and deductive reasoning [5].

The outcome of the assessment procedure is a conclusion that none of the available alternatives adequately fulfill the design specifications. Under such circumstances, the designer seeks novel concepts yet may realize that the analytical results from the prior evaluation do not substantially aid in identifying designs closer to the intended objective. The inability of the evaluative stage of design to guide or constrain the creative phase causes the process to operate in an open-loop manner, which does not readily converge on a favorable design option. Since there are no universal principles enabling designers to appraise design options and select effective solutions without extensive study or expertise, promising designs are sometimes rejected, and the design process may require additional time to achieve an acceptable outcome [12].

1.2. Literature review of network structures

In recent years, increasing attention has been directed toward examining the spatial dynamics of innovative activities and their implications for economic agglomeration. This focus is particularly pronounced in studies investigating clusters of small and medium-sized enterprises operating within technology-intensive industries. Growing acknowledgment that variations in regional economic performance and development are influenced by a constellation of determinants and resources, including intellectual assets, qualified labor, and institutional and organizational structures, has generated a revitalized focus on spatiality and territorial context. Empirical evidence indicates that the dissemination of new knowledge transpires more efficiently among geographically proximate actors. Crucially, the circulation of knowledge can only be realized through human interaction and the temporary mobility of workers. The primary factor attracting firms into concentrated groups, and the fundamental condition for the enduring dynamism of innovation clusters, is the integration of networking with learning derived from interaction. These clusters promote the circulation of knowledge through user and producer connections, officially and unofficially collaborations, the transfer of skilled professionals among firms, and the establishment of new ventures originating from existing research institutions enterprises and universities.

The capacity to find and keep robust social networks and communication channels constitutes a prerequisite for firms to gain access to localized reservoirs of knowledge and competencies. Within the framework of an innovation system, an extensive body of scholarship on innovation clusters has evolved. This perspective has approached innovation as a dynamic process shaped by interactions among diverse actors. This highlights that firms engage in innovation within interconnected environments, framing innovation as a collective rather than solitary process. Accordingly, an analysis of innovation clusters would be inadequate without incorporating insights from the social network perspective.

Through the analytical instruments and methodologies derived from social network analysis and graph theory, it becomes essential to model and empirically evaluate the various network effects assumed to be fundamental to the effective functioning of clusters, particularly by applying the small-world approach.

A substantial body of academic research highlights the significance of understanding organizational network structures for assessing how decisions influence overall organizational performance. Rather than being dictated primarily by formal hierarchies, patterns of coordination and operational processes are shaped predominantly by informal relational networks, including those of communication, information exchange, and problem-solving. Moreover, the complexities inherent in product development underscore the indispensability of sustained interactions within such networks. A persistent tension exists between the processes of knowledge creation and knowledge diffusion. This challenge can be addressed through a network topology commonly referred to as the small-world structure [13], [14]. Such networks simultaneously exhibit a high degree of clustering while maintaining relatively short path lengths between agents [15].

2. Assessment of existing design procedures among micro-scale enterprises

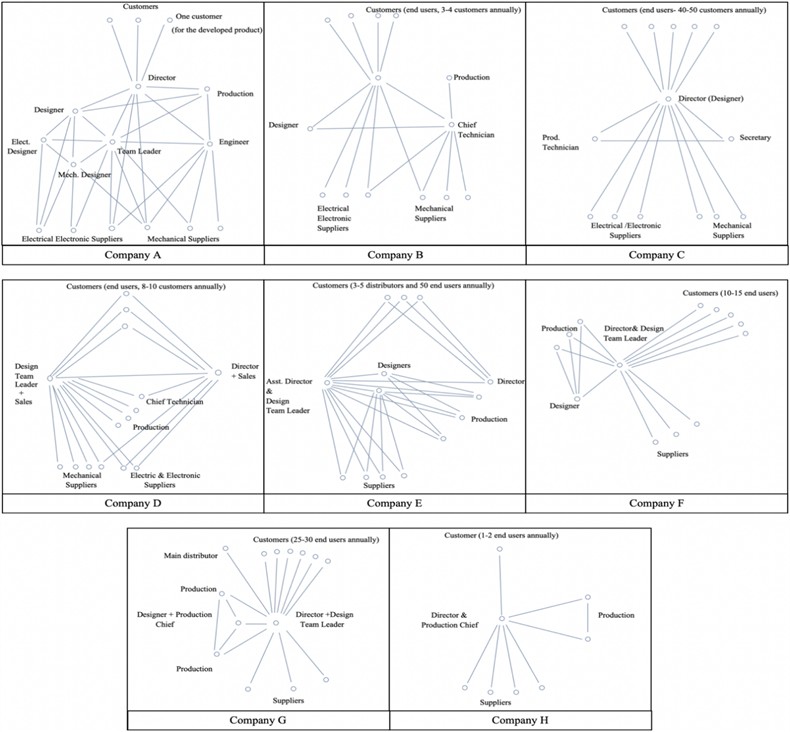

Product development approaches of micro-scale enterprises within the European industrial sector are examined through interviews conducted with eight firms situated in organized industrial zones. These enterprises employ fewer than ten individuals, thereby conforming to the definition of micro-scale Enterprises. Through interviews with the selected firms, comprehensive information regarding their product development phases is acquired.

Initially, the firms were asked to complete survey forms. Following this, the information gathered from interview records served as the basis for a structured question-and-answer session aimed at eliciting more comprehensive insights into their product development practices. The investigation centered its attention on key operational dimensions, including talent management and workforce allocation, temporal organization and strategic roadmaps, the sequence and substance of project execution phases, integrated communication frameworks, iterative model fabrication, and the systematic recording of procedural workflows.

2.1. Product/process design and development processes in enterprises

In this section, the findings derived from comprehensive focuses group interviews and questionnaires are synthesized, and parallels are drawn with design development methods employed by both small and large enterprises.

Table 1 presents the product and process development practices of the Enterprises [16]. Further concise information regarding the firms and their respective development resources is elaborated in the subsequent sections.

2.1.1. Enterprise A

Enterprise A engages in the manufacture of hospitality service equipments. The distribution of personnel is as follows:

– Secretary.

– Production (1 White-collar, 5 Blue-collar).

– Design team (1 White-collar, 3 Blue-collar).

– Enterprise director (White-collar, technical background).

The product and process development strategy of Enterprise A is presented in Table 1. The firm’s product design and enhancement activities are largely shaped by customer requirements. In addition, spontaneous market opportunities and improvements to existing products are integrated into the Enterprise’s development practices. The Enterprise director plays a central role in promoting products in both domestic and international markets, while systematically gathering customer feedback and monitoring potential market opportunities.

Table 1Product/Process design and development activities of enterprises

Enterprises | Project title | Product/process development factor | ||

Customer demand | Immediate market prospects | Development on current product | ||

Enterprise A | Market equipment | + | ||

Food equipment | + | + | + | |

Enterprise B | Production of water bottles | + | ||

Enterprise C | Endoscopic camera manufacturing | + | ||

Enterprise D | CNC turret lathe | + | + | |

Enterprise E | Wood shaping machine | + | ||

Wood Shaping machine radial | + | + | ||

Enterprise F | Plastic injection molds | + | ||

Aluminum die casting molds | + | |||

Enterprise G | Food pumps manufacturing | + | + | |

Enterprise H | Steel profile manufacturing machine | + | ||

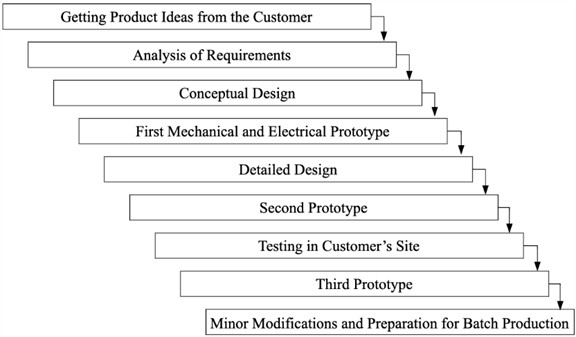

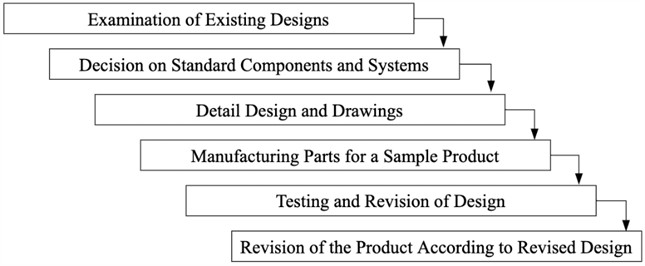

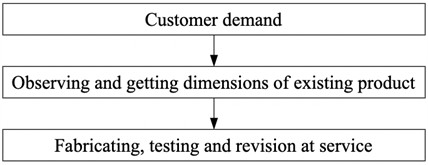

Based on the conducted interviews and investigations, the stages of product design and development within Enterprise A can be illustrated as in Fig. 1. The organization collaboratively collects ideas with the customer. Prior to the detailed design phase, several conceptual designs are generated in accordance with the requirements. Multiple prototypes are produced at successive stages of design, with necessary revisions and modifications applied. Following the evaluation of the final prototype, several samples are typically produced for field testing during the pilot production stage, which simultaneously serves as preparation for subsequent batch production [16].

Fig. 1Product/process development stages of Enterprise A

2.1.2. Enterprise B

Enterprise B specializes in the manufacture of water bottle production machinery. The organizational structure of employees is as follows:

– Secretary.

– Production (2 technicians, 3 workers).

– Design team (1 White-collar).

– Enterprise director (White-collar, technical background).

Collaboration between the design and the production teams are limited. Externally manufactured components are often defective. The technical drawings are transferred to external manufacturers without undergoing a joint evaluation by both the production and design units.

The product/process development strategy adopted by Enterprise B is presented in Table 1. Customer demand primarily directs the activities of product development and improvement. Consequently, the improvement of products currently in production is grounded in customer requirements. Although the director monitors market opportunities and systematically gathers information, the development of products in response to immediate market opportunities proves challenging. The creation of such machines necessitates substantial financial investment, extended research and development efforts, and a highly competent design and production team capable of gathering information and carefully monitoring market conditions.

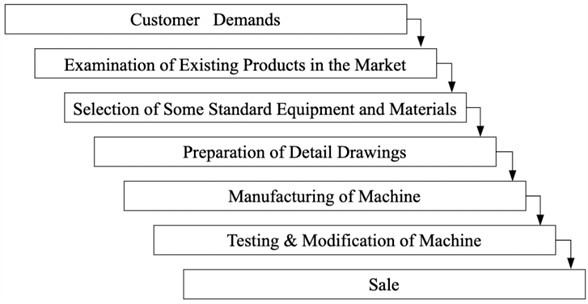

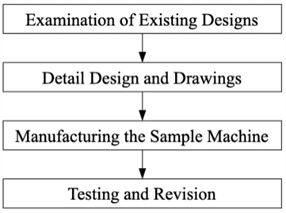

Enterprise B implements a sequential design process as illustrated in Fig. 2. As the Enterprise manufactures relatively large machines individually, the possibility of producing a prototype or a sample product is almost nonexistent. For this reason, the Enterprise initiates manufacturing directly after completing the technical drawings. Certain standard equipment and materials can be procured during production. Fig. 2 further demonstrates that product testing is conducted on the final manufactured product, although numerous tests are carried out during various stages of production [16].

Fig. 2Product/process development stages of Enterprise B

2.1.3. Enterprise C

Enterprise C specializes in the production of endoscopic cameras for the medical industry. The enterprise was founded by the director, who holds a Ph.D. in Electronic Engineering. The organizational structure of the Enterprise is as follows:

– One secretary.

– One technician.

– Director.

In total, the Enterprise employs three individuals, all working on a full-time basis. The two additional personnel at Enterprise C possess qualifications from high school and vocational training institutions.

The director systematically observes global market opportunities, as presented in Table 1, which outlines the product development strategy of Enterprise C. He subsequently formulates and improves the product in alignment with customer demand. The feedback received from customers is incorporated provided that the product development process does not necessitate substantial revisions or replacement of parts.

The Enterprise lacks an effective quality control mechanism for both its production processes and the supplied components. Alongside product development activities, it is essential for the Enterprise to establish a comprehensive quality control strategy addressing not only in-house production but also the parts procured from external suppliers.

Enterprise C employs an abbreviated sequence of product/process development and improvement stages, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The organization determines the product to be developed through an examination of market opportunities. Subsequently, the director procures the required standard equipment and materials. All mechanical components are produced by external firms without the provision of part drawings. The prototype is then assembled and subjected to testing. Ultimately, the procedure concludes with a limited batch production intended for commercial distribution [16].

Fig. 3Product/process development stages of Enterprise C

2.1.4. Enterprise D

Enterprise D specializes in the manufacture of CNC Turret Lathes. The distribution of personnel across the Enterprise departments is as follows:

– Enterprise director (White-collar, technical background).

– Production (1 technician, 5 workers).

– Design team (3 Blue-collar).

Distinct from the other firms interviewed, the director of Enterprise D primarily administers general management and coordinates financial matters. Although the director is not directly engaged in product or process development, consultation on developmental and improvement issues is carried out with him when necessary.

Enterprise D manufactures conventional turret lathes while simultaneously developing CNC turret lathes for the domestic market (Table 1). Furthermore, the Enterprise seeks to expand into international markets with the introduction of the new “CNC Turret Lathe.” The leader of the design team, who is also an Enterprise shareholder and the director’s brother, is a technician. He is responsible for managing product and process development, production, and procurement. When critical issues arise, he provides information to and consults with the director. Enterprise D implements its design methodology as outlined in Fig. 4 [16].

2.1.5. Enterprise E

The core production line of Enterprise E consists of wood-shaping machinery. The firm systematically examines existing designs available in the market as part of its operational approach. The distribution of roles and responsibilities within the Enterprise is outlined as follows:

– Enterprise director (Blue-collar, technical background).

– Design Team Leader (White-collar, family member).

– Design Team (2 Blue-collar, technical background).

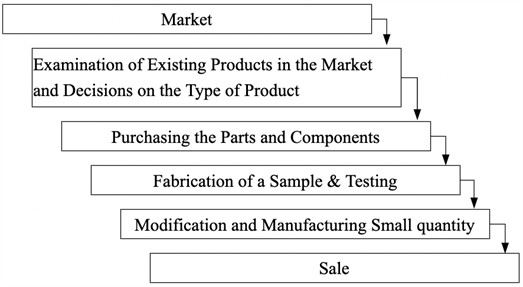

– Production (White-collar, 5 Blue-collar).

Enterprise E manufactures wood shaping machines and has recently developed a model capable of cutting along two radial axes. The product development strategy of Enterprise E is presented in Table 1. This innovation, termed the radial wood shaping machine, operates with equivalent capacity yet accommodates larger dimensions. In order to develop this product, the Enterprise initially acquired and examined existing market samples, followed by the design of an enhanced model. The firm employed high-quality components and incorporated additional features to improve usability and serviceability. The design team leader exercises full authority over the product development department. The Enterprise adheres to the design methodology illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4Product/process development stages of Enterprise D

Fig. 5Product/process development stages of Enterprise E

Enterprise E employs a straightforward product development process as illustrated in Fig. 5. Following the assessment of existing designs, the design team chooses the standard components and produces the detailed drawings. Subsequently, the production department fabricates a prototype, conducts testing, implements the necessary modifications, and initiates batch production [16].

2.1.6. Enterprise F

The primary products of Enterprise F are plastic injection molds and aluminum die-casting molds.

The organizational structure of Enterprise F is as follows:

– Enterprise director (White-collar, technical background).

– Design team leader (Enterprise director).

– Design team (1 Blue-collar, technical background).

– Production (3 Blue-collar).

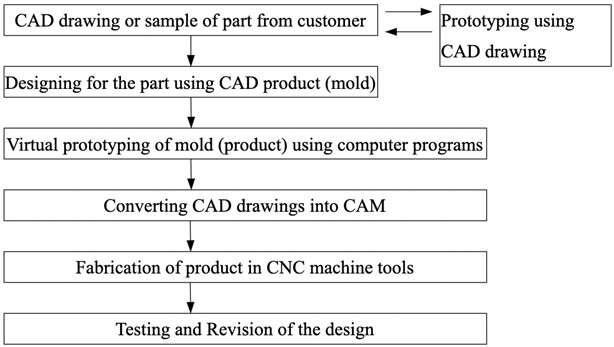

In Enterprise F, as the director assumes the role of designer, he exercises full authority over the design process. The designer assisting the director primarily prepares CAD drawings, while the director independently delivers the final decision. The product design activities of Enterprise F are determined exclusively by customer demand, as indicated in Table 1. Based on the client’s request, either a CAD drawing or a sample component is obtained. Subsequently, the corresponding mold is designed and manufactured. In this Enterprise, each product is treated as unique, and for every individual product a complete design and development procedure is carried out.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, when mold production is considered, the Enterprise follows a design procedure that diverges slightly from conventional product design stages. Upon completion of the final CAD drawing of the part, the design phase is concluded, and virtual prototyping is undertaken. In cases where a physical sample of the part is available, reverse engineering methods are applied. Using a three-dimensional coordinate measuring machine, the part is measured and subsequently transformed into a CAD model. Since production is limited to a single unit, physical prototyping is not a viable option. Therefore, after the virtual prototype is generated, the product is manufactured directly using CNC machining centers. The manufactured components are assembled and tested, with necessary revisions performed if discrepancies with the original sample are detected. Historically, no documentation had been maintained for the products; however, the Enterprise has more recently adopted the practice of creating a dedicated file for each product and recording the entire design and manufacturing history [16].

Fig. 6Product/process development stages of Enterprise F

2.1.7. Enterprise G

Enterprise G specializes in the manufacture of food pumps. The Enterprise personnel structure is as follows:

– Enterprise director (Blue-collar, technical background).

– Designer & Production Chief (Blue-collar, technical background).

– Production (2 Blue-collar).

The product design and development approach of Enterprise G is presented in Table 1. The director established the business three decades ago, at the age of fourteen. Initially, the Enterprise focused on producing fuel pumps for gas stations. Subsequently, the firm began to receive contracts for the manufacture of food pumps. The director systematically observed operational products in industrial plants and examined market samples, leading the Enterprise to initially replicate similar products. At present, the firm designs and manufactures pumps of greater capacity, specifically adapted for liquid foods characterized by high viscosity and challenging pumping requirements.

Fig. 7 presents the stages of product design. The Enterprise follows a straightforward design and development process since the designed product does not demonstrate substantial differences from the existing product available in the market [16].

Fig. 7Product/process development stages of Enterprise G

2.1.8. Enterprise H

The product of Enterprise H consists of machines for manufacturing square and rectangular cross-sectional tubes.

The list of employees:

– Enterprise director (Blue-collar, technical background).

– Production (2 Blue-collar, technical background).

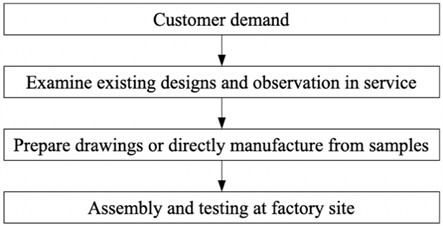

Enterprise H does not engage in formalized product development activities. The company specializes in producing large-scale machines customized to meet specific customer requirements, as summarized in Table 1. Its business activities are restricted to the domestic market, with the product preparation phase typically spanning 2-3 months.

Overall, by examining products available in the market and gathering dimensional data, the primary frame of the machine is designed, followed by the integration of standardized components with custom-fabricated elements on the main frame. Completing the product from initial conception to finalization generally requires approximately 6 to 8 months. Although a formalized product development procedure is not in place, the Enterprise observes the fundamental stages of product design and development, as illustrated in Fig. 8 [16].

Fig. 8Product/process development stages of Enterprise H

2.2. Integration of the product development and improvement processes of examined firms

Obtaining coherent responses from Enterprises for this investigation proved highly challenging. Firms appeared reluctant to disclose any substantive information. The principal insights derived from these inquiries are summarized as follows:

– The Enterprises generally perform certain conventional stages of new product development. However, these processes are often retained solely within the minds of specific individuals in the organization. They are neither systematic nor explicitly articulated and remain undocumented.

– Enterprise A demonstrates a comparatively stronger position regarding new product development. Nonetheless, fewer than 10 % of enterprises within the micro-scale category exhibit comparable characteristics. The remainder align more closely with Enterprises B and C. In the second phase of interviews, five additional micro-scale firms, designated D through H, were examined. The design behaviors of these firms closely resemble those of Enterprises B and C. While Enterprises D and E approximate a fully connected network structure, their design practices nonetheless require greater systematic organization.

– These firms lack organizational memory that could support them during crises, such as the departure of a critical team member. This deficiency is clearly reflected in their internal and external network diagrams. Certain individuals occupy key nodes within the network, and the removal of such nodes could precipitate significant network failure. Recovery would be prolonged due to the absence of adequate documentation.

3. Small-world network structure measurements of enterprises

The rigorous definition of a simple graph is an ordered pair , where stands for the set of vertices and for the set of edges. Each element of establishes a link between and its end-vertices, which are an unordered pair of different vertices from [30].

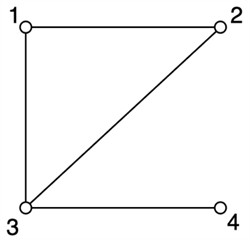

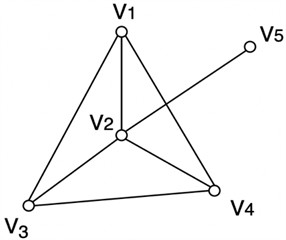

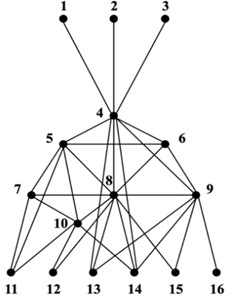

In this context, the elements of are called edges. An edge connects two vertices, its end-vertices. In graphical illustrations, vertices are represented as points, while edges are depicted as lines. For example, a graph with {1, 2, 3, 4} and is illustrated in Fig. 9 [17].

Let be a graph. The degree of a vertex is defined as the number of edges incident to . The neighborhood of a vertex is the set of all vertices adjacent to . Consequently, , as illustrated in Fig. 10. For the given graph, the cardinalities of the neighborhoods are:, and [16].

Fig. 9A diagram of graph

Fig. 10Set of neighbors of a graph

Another fundamental principle: the sum of all vertex degrees in a simple graph equals twice the total number of edges. The sum of degrees of all vertices is 14 and number of edges is 7 in Fig. 10.

Within small-world network theory, two critical topological characteristics are emphasized: the average path length and the clustering coefficient . The small-world phenomenon is characterized by a low , typically scaling logarithmically with node count, and a significantly elevated , surpassing values expected in equivalent random graphs [18].

Formally, the average path length is defined as in Eq. (1):

In the second stage of network analysis, the clustering coefficient is computed. A high degree of clustering, also referred to as transitivity, indicates an increased likelihood that two vertices will be directly connected when they share a common neighbor. Within the context of social networks, this corresponds to the idea that two individuals are more likely to know each other if they both have a mutual acquaintance.

For any given node , the local clustering coefficient, , is defined as the ratio of the number of actual connections between the neighbors of to the total number of all possible connections among those neighbors [31]. Since the maximum number of potential links between the neighbors of node is given by , the expression in Eq. (2) naturally follows:

The global clustering coefficient is then given in Eq. (3):

A high clustering coefficient implies, in the context of social networks, that two of an individual’s friends are also likely to be friends with each other. This reflects a high degree of redundancy within the network. In the case of a complete graph , the clustering coefficient is trivially equal to 1.

The neighborhood of a set of vertices is defined as the collection of all vertices adjacent to at least one element of the set, excluding the set itself. For a single vertex , the neighborhood of is denoted by . The induced subgraph on , written as , has vertex set , and its edge set consists of all edges with both endpoints in . We denote by the number of vertices and by the number of edges in . The clustering coefficient of vertex is then expressed as shown in Eq. (4) [19], [20]:

Equivalently, the local clustering coefficient of a vertex can be expressed as the ratio of the number of existing links among its neighbors to the maximum possible number of such links.

For a graph , the clustering coefficient is defined as the average of the local clustering coefficients of all its vertices and is denoted by , or more concisely . The upper extreme value arises precisely when is composed of several disjoint complete graphs of identical order, each with vertices such that every vertex has degree . Conversely, the lower extreme value is obtained when contains no triangular substructures [21].

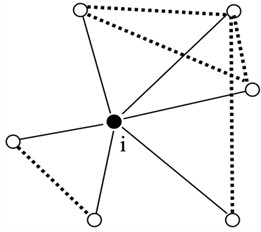

Consider Fig. 11, which represents the immediate neighborhood of a vertex in a given network. Vertex has six adjacent vertices, indicated by solid lines in the figure. Hence, the number of possible neighbor pairs is given by 1/2 * 6 * 5 = 15. Among these, five pairs are directly connected, shown by dotted lines. The local clustering coefficient of vertex is therefore defined as the ratio of these connected pairs to the total possible pairs, i.e., 5/15. The overall clustering coefficient of the network is then obtained by averaging this measure across all n vertices.

In Fig. 11, only five out of the fifteen possible connections among the neighbors are realized (illustrated by dotted lines). For a fully connected graph, where each vertex is linked to every other the clustering coefficient takes the value . By contrast, in random graphs the probability that any two vertices are connected is given by , where represents the average degree and denotes the number of vertices [22]. Consequently, in a random network the clustering coefficient is expressed as , which typically assumes a very small value for the ranges of and observed in real-world networks. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that in such cases the clustering coefficient of real-world graphs is significantly larger than [22], [23].

The relevance of analyzing organizational network structures as a means to evaluate how decision-making influences organizational performance has been widely emphasized in the literature of social sciences and management [24].

Fig. 11The central vertex i and its six neighbors

3.1. Calculation of network measurements

Network measures are employed to determine significant structural properties, including the characteristic path length and the clustering coefficient, for the examined firms by utilizing both internal and external network systems as illustrated in Fig. 12. In this section, the network metrics are computed for Enterprise A. The characteristic path length L and the clustering coefficient C are derived according to Eq. (1) and Eq. (4) for illustrative purposes.

Fig. 12Internal and external network system of Enterprises

As illustrated in Fig. 13 (the numbered representation of Fig. 12 concerning Enterprise A), the network consists of 16 nodes and 32 links. Beginning with the path from 1 to 4, followed by 2 to 4, … (in accordance with Eq. (1)), and by enumerating the minimum number of edges between each pair of nodes, we obtain a total of 237 minimum path lengths across the network. If the nodes were fully interconnected, this value would be calculated as be 1/2 * 16 * 15 = 120. Consequently, the mean path length among nodes is determined as 237/120 = 1.98 [16]

Fig. 13Internal and external network structure of Enterprise A (nodes are numbered)

The computation of the cluster coefficient relies on Eq. (4) and Fig. 13. Node 1 possesses only node 4 as a neighbor; therefore, when the link between node 1 and node 4 is eliminated, no connections remain. Consequently, . In a similar manner, . Node 4 has nodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, and 14 as neighbors. If the links connecting node 4 to its neighbors are excluded, only 9 connections remain among these neighbors out of the possible 1/2 * 9 * 8 = 36 regular connections between nodes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, and 14. Therefore, = 9/36 = 0.25. Continuing in this manner, we obtain 16/30 = 0.5, 8/12 = 0.667, 10/12 = 0.834, 24/90 = 0.267, 14/42 = 0.335, 12/30 = 0.4,6/6 = 1,= 2/2 = 1, 6/6 = 1, 8/12 = 0.667, 2/2 = 1, and = 0. Accordingly, based on Eq. (4), the overall value is 7.95/16 = 0.496.

Accordingly, for Enterprise A, the characteristic length of the network is 1.98 and the clustering coefficient is 0.496. These values indicate the properties of a small world network, allowing us to infer that the Enterprise demonstrates innovative and productive tendencies. The characteristic path length and the clustering coefficient of all Enterprises are determined by applying Eq. (1) and Eq. (4) in the same manner as for Enterprise A. The outcomes of these calculations are presented in Table 2 [16].

Table 2Computed network parameters for the enterprises examined

Enterprise | Characteristic path length, | Cluster coefficient, |

A | 1.98 | 0.496 |

B | 1.98 | 0.224 |

C | 1.88 | 0.04 |

D | 1.74 | 0 |

E | 1.82 | 0.93 |

F | 1.92 | 0.063 |

G | 1.92 | 0.2 |

H | 1.75 | 0.226 |

The characteristic path length and the clustering coefficient constitute significant parameters for innovative networks. Networks of firms that reflect innovativeness and productivity should display a characteristic path length that is minimized and a clustering coefficient that approaches the value of 1. Based on our empirical analysis, as presented in Table 2, the characteristic path length is observed to be below 2, while the clustering coefficient ranges between 0 and 0.93. Enterprises A and E exhibit a structure resembling the small-world type. These firms demonstrate relatively strong collaborations among internal agents as well as diverse relational pathways to external customers and suppliers.

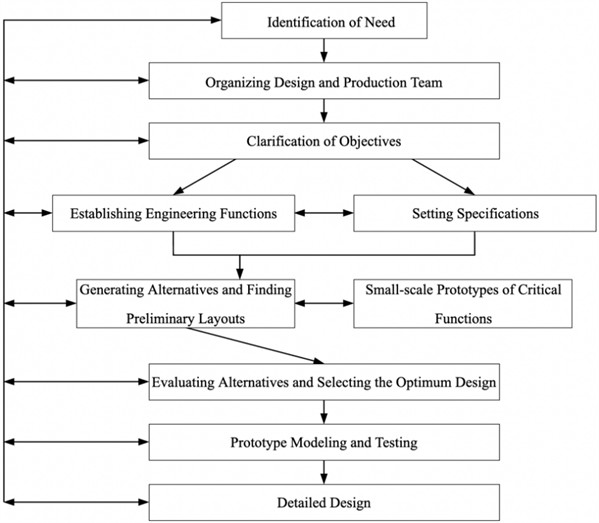

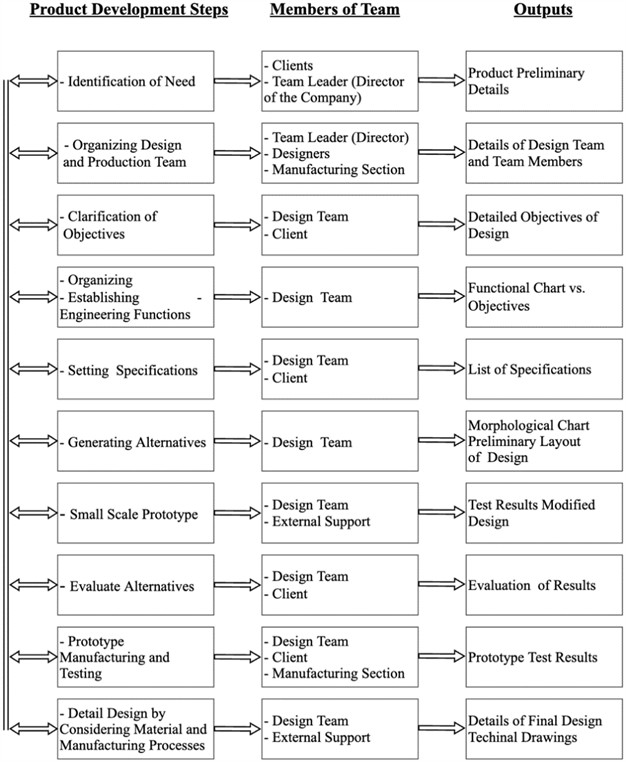

4. Developing a new product/process design system for micro scale industrial enterprises

The interviews and investigations carried out with enterprises extended over a period exceeding one year. During this timeframe, eight enterprises, designated A through H, were examined in detail. In addition, collaboration was established with more than fifteen other enterprises to obtain broader insights into their approaches to product design and development activities. Based on the comprehensive information gathered, a fundamental design methodology was constructed by analyzing a set of criteria specifically developed to guide micro-scale enterprises. This structured framework for product design and development is intended to support and streamline the product development processes of such enterprises.

The proposed framework not only shortens the overall duration of product development but also assists enterprise staff in strengthening internal communication while fostering greater efficiency throughout the development cycle. The flowchart illustrating the sequential stages of this framework is provided in Fig. 14. It presents the essential stages and strategies to be adopted by micro-scale enterprises and incorporates ten core design steps adapted from existing design models. These steps have been adjusted to reflect the operational and employment characteristics of micro-scale enterprises, with parallel stages indicating processes that can be executed concurrently.

Fig. 14Flowchart of proposed product/process design and development steps

Fig. 15 illustrates the proposed framework for product design and development. At each stage, both the responsible participants and the corresponding outputs are explicitly identified. The framework is characterized by the inclusion of a feedback mechanism that functions across intra- and inter-organizational levels. Furthermore, the conclusion of every stage necessitates the articulation of a specific output, thereby ensuring that the overarching goals of effective product design and development in micro-scale enterprises are systematically achieved.

In this model, the product design and development process begins with the identification of needs and concludes with the preparation of the detailed design. Transitions between stages may involve multiple iterations. At the end of each phase, team members systematically document the outcomes, which are then consolidated into a formal record. Such documentation holds particular importance for micro-scale enterprises. In cases where a design team member is unavailable, the records serve as a structured guide that ensures continuity of the process. Moreover, the documentation acts as a long-term reference, granting the enterprise access to the historical trajectory of product design and development activities.

Fig. 15Proposed product design and development model

5. Conclusions

A wide range of design methodologies has been proposed to enable the systematic and efficient development of new products with the aim of strengthening competitiveness. However, these approaches are primarily suited to small-, medium-, and large-scale enterprises, where the workforce typically includes at least five to ten engineers. By contrast, micro-scale enterprises often employ only one or two engineers or in some cases none at all which creates substantial difficulties in product development and in sustaining competitive advantage. The methodologies currently available are not tailored to their structural constraints, and no viable alternatives have yet been formulated to adequately address their needs.

This research introduces a novel methodology designed to support micro- and small-scale enterprises in the development of new product designs. The proposed framework can be employed both for the creation of entirely new products by firms with no prior design experience, and for the redesign of existing products. For example, a firm producing car brake shoes may wish to develop brake pads for axial brakes, or alternatively, may seek to build upon an earlier design by replacing conventional brake pads with a computer-controlled braking system that retains elements of the prior configuration. Similarly, incremental product modifications such as adapting specific characteristics of brake shoes to meet customer expectations can also be effectively managed through this methodology.

Analysis of the internal and external network configurations of several examined enterprises revealed patterns resembling the “small-world” type of network. Nevertheless, significant variation exists across firms in their approaches to product development and organizational structure. As network configurations move closer to the small-world model, enterprises tend to display higher levels of productivity and stronger innovation capacity. To draw robust conclusions, further examination of a larger set of enterprise networks is required; nonetheless, this study provides an initial step in that direction.

Despite the proliferation of product design methodologies, micro-scale enterprises remain underserved by existing models, which presume larger teams and more formalized processes. This study identifies this gap and responds by developing a tailored framework that integrates structured design steps with an analysis of organizational network properties. The aim is not only to streamline product development in resource-constrained settings but also to enhance innovation through improved internal and external collaboration mechanisms.

Future research should extend beyond the micro-scale enterprises of European industrial regions to encompass broader inter-firm network structures and to compare these dynamics with those observed in innovative industrial clusters worldwide. Such comparative analyses may reveal structural impediments that constrain product development capacities in specific contexts. As innovation emerges and diffuses through networks of communication and collaboration among firms, the configuration of these networks particularly those linking micro-enterprises with small- and medium-sized enterprises warrants careful examination. A deeper understanding of these structures is essential for strengthening innovation capability and improving productivity across organizational ecosystems.

References

-

S. Slávik, N. Jankelová, I. M. Hudáková, and J. Mišún, “Determinants of the growth of Small and Medium Enterprises,” Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 480–497, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2023.11.2(32)

-

T. Kastelle and J. Steen, “Are small world networks always best for innovation?,” Innovation, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 75–87, Dec. 2014, https://doi.org/10.5172/impp.12.1.75

-

T. Kastelle and J. Steen, “New methods for the analysis of innovation networks,” Innovation: Management, Policy and Practice, Vol. 12, 2010.

-

A. Feyzioglu and A. K. Kar, “Axiomatic design approach for nonlinear multiple objective optimizaton problem and robustness in spring design,” Cybernetics and Information Technologies, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 63–71, Mar. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1515/cait-2017-0005

-

N. Cross, Engineering Design Methods: Strategies for Product Design. John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

-

N. Crilly, “Creativity and fixation in the real world: A literature review of case study research,” Design Studies, Vol. 64, pp. 154–168, Sep. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2019.07.002

-

V. Carneiro, B. Rangel, J. Lino Alves, and A. Barata Da Rocha, “The path to integrated project design (IPD) through the examples of industrial/product/engineering design: a review,” Digital Innovations in Architecture, Engineering and Construction, pp. 167–196, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32425-3_7

-

D. C. Wynn and P. J. Clarkson, “Process models in design and development,” Research in Engineering Design, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 161–202, Jul. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00163-017-0262-7

-

G. Pahl, W. Beitz, J. Feldhusen, and K.-H. Grote, “Engineering design,” in Mrs Bulletin, London: Springer London, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84628-319-2

-

V. Hubka, Principles of Engineering Design. Elsevier, 2015.

-

K. Simmonds, “Marketing as innovation the eighth paradigm,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 23, No. 5, pp. 479–500, May 2007, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1986.tb00433.x

-

N. Cross, Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023.

-

C. Phelps and M. A. Schilling, “Interfirm collaboration networks: the impact of small world connectivity on firm innovation,” Academy of Management Proceedings, Vol. 2005, No. 1, Aug. 2005, https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.2005.18783570

-

B. Uzzi, L. A. Amaral, and F. Reed‐Tsochas, “Small‐world networks and management science research: a review,” European Management Review, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 77–91, Dec. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.emr.1500078

-

B. Malerba, Clusters, Networks and Innovation. Oxford University PressOxford, 2005, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199275557.001.0001

-

E. Kuşak, “Development of a product design system for micro scale industrial companies and investigation of their network structures,” Marmara University, 2009.

-

C. Grabow, S. Grosskinsky, J. Kurths, and M. Timme, “Collective relaxation dynamics of small-world networks,” Physical Review E, Vol. 91, No. 5, May 2015, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.91.052815

-

S. Ameli, M. Karimian, and F. Shahbazi, “Time-delayed Kuramoto model in the Watts-Strogatz small-world networks,” Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, Vol. 31, No. 11, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0064022

-

M. Nasrolahzadeh, Z. Mohammadpoory, and J. Haddadnia, “Small-world networks propensity in spontaneous speech signals of Alzheimer’s disease: visibility graph analysis,” Scientific Reports, Vol. 15, No. 1, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88947-9

-

R. Zhang and B. Zhu, “A multiobjective evolutionary algorithm for optimizing the small-world property,” PLOS ONE, Vol. 19, No. 12, p. e0313757, Dec. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0313757

-

Y. Shao, “Graph-enhanced learning and optimization for real-world applications,” The Florida State University, 2025.

-

S. Boccaletti et al., “The structure and dynamics of networks with higher order interactions,” Physics Reports, Vol. 1018, pp. 1–64, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2023.04.002

-

S. Bazzaz Abkenar, M. Haghi Kashani, E. Mahdipour, and S. M. Jameii, “Big data analytics meets social media: A systematic review of techniques, open issues, and future directions,” Telematics and Informatics, Vol. 57, p. 101517, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101517

-

L. Deng and S. Liu, “Unlocking new potentials in evolutionary computation with complex network insights: a brief survey,” Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, Jun. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-025-10307-7

-

G. G. Calabrese and A. Manello, “Firm internationalization and performance: evidence for designing policies,” Journal of Policy Modeling, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 1221–1242, Nov. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2018.01.008

-

S. Chowdhury et al., “Botnet detection using graph-based feature clustering,” Journal of Big Data, Vol. 4, No. 1, p. 14, May 2017, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-017-0074-7

-

E. Souzanchi Kashani and S. Roshani, “Evolution of innovation system literature: Intellectual bases and emerging trends,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 146, pp. 68–80, Sep. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.05.010

-

S.-W. Kwon, E. Rondi, D. Z. Levin, A. de Massis, and D. J. Brass, “Network brokerage: an integrative review and future research agenda,” Journal of Management, Vol. 46, No. 6, pp. 1092–1120, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320914694

-

S. Majhi, M. Perc, and D. Ghosh, “Dynamics on higher-order networks: a review,” Journal of The Royal Society Interface, Vol. 19, No. 188, Mar. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2022.0043

-

A. K. Naimzada, Networks, Topology and Dynamics: Theory and Applications to Economics and Social Systems. Springer Science and Business Media, 2008, pp. 978–3.

-

E. Ravasz, A. L. Somera, D. A. Mongru, Z. N. Oltvai, and A.-L. Barabási, “Hierarchical organization of modularity in metabolic networks,” Science, Vol. 297, No. 5586, pp. 1551–1555, Aug. 2002, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1073374

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ahmet Feyzioglu: conceptualization, methodology development, investigation, data analysis, and manuscript writing. Ahmet Feyzioğlu also served as the corresponding author and oversaw the overall research process. Eyyup Kuşak: conducted SME interviews and data collection in Belgium, contributed to the analysis of regional product development practices, and provided feedback on the manuscript. Abdulkerim Kar: conducted SME interviews and data collection in Turkey, contributed to the identification of technical challenges in SMEs, and assisted in drafting specific sections of the manuscript. Donatella Santoro: conducted SME interviews and data collection in Italy, contributed to exploring SME network architectures, and provided insights into regional engineering practices. Leonardo Piccinetti: provided strategic input from Ireland, contributed to understanding global competition factors, and reviewed the manuscript for alignment with the study’s goals. Trevor Uyi Omoruyi: conducted SME interviews and data collection in England, contributed to the analysis of technical employee interactions within SMEs, and provided editorial suggestions to refine the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.