Abstract

Physical exercise promotes benefits for people with chronic kidney disease, but little has been investigated on the effects of strength training using the blood flow restriction method. The objective is to present the intervention protocol with strength physical exercise associated with the RFS method for people with stage 3 CKD and to report the benefits in the hemodynamic scope and personal satisfaction after 4 weeks of exposure to physical exercise. The study is an intervention protocol proposed to be developed over 12 weeks, with 9 exercises, in people with CKD-3, on 3 days a week lasting 50 minutes. The participants were divided into groups with low load, with high load and group with blood flow restriction and hemodynamic variables (blood pressure and heart rate) and affective satisfaction in relation to the proposed exercise were measured. Forty people aged 58±8.9 years were recruited, of which 30 participated in the intervention. Regarding satisfaction, the high-load group presented better results (2.8 to 3.5) (0.035); and for blood pressure, the blood flow restriction group showed significance in systolic pressure (0.034). It is concluded that after 4 weeks of intervention with a strength training protocol aimed at blood flow restriction, there are trends of improvements in systolic blood pressure levels, and affective sensations were improved after the end of the exercise sessions.

Highlights

- Development of a strength training protocol with and without flow restriction to evaluate the hemodynamic effect over 4 weeks in pacientes with kidney chronic disease.

- There were tendencies to improve systolic blood pressure levels when using the blood flow restriction method.

- However, when evaluating the effective satisfaction of the training, even though there were clinical improvements when using the method, training with a high load can show significant changes.

- It is hoped that over the course of 12 weeks, the period of validity of the research, new benefits can be reported for its use in other training environments that are not exclusively clinical and scientific.

1. Introduction

Physical exercise has been used as an essential non-pharmacological resource to improve morphological, physiological, and behavioral parameters and physical performance in numerous treatments for clinical conditions, chronic diseases, and health problems [1], [2]. In addition, the regular practice of these activities has been shown to improve adherence to and the effects of treatments for diseases with more severe interventions such as cancer, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, mental disorders, stroke, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [3].

CKD can be characterized as a progressive, irreversible, and chronic loss of kidney function [4]. The stages of the disease's evolution are determined by the loss of the kidneys' ability to filter solutes, corroborating the development of more advanced stages of the disease that require renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and/or transplantation) [5]. However, before this time, the conservative phase of treatment allows people to regulate the disease through physical activity, dietary restrictions, a reduction in risky behaviors (excessive use of alcohol and tobacco), as well as the use of medication to control glycemic, inflammatory and blood pressure parameters [6], [7].

However, even though research has been done on the impact of physical exercise on this population [8], levels of physical activity are still below those recommended, for example, by the Physical Activity Guide for the Brazilian Population and the World Health Organization [9], [10]. Taking strength and aerobic exercise into account, studies have shown an improvement in functional capacity (strength and respiratory conditioning), glycemic levels, hemodynamics, kidney function, metabolic aspects (body mass, body mass index, body composition), perceived quality of life and well-being [11]-[13].

Recently, strength training has been associated with the blood flow restriction (BFR) method to verify beneficial changes in healthy populations. BFR causes an environment of hypoxia in muscle tissue, inducing metabolic stress due to the internal acidity of the muscle triggered during training, which in turn corroborates an increase in hormonal expression for recovery and regeneration of muscle tissue [14], [15]. In this sense, benefits such as increased muscle strength [16]; hypertrophy [17], [18], regulation of blood pressure increase [19]; changes of 40 % and 60 % of VO²max in aerobic exercise protocols [20]; and hematological, biochemical and hormonal parameters [21].

For the CKD population, some recently reported benefits include metabolic and blood pressure gains, increased dynamic strength, improved functional capacity, vascularization for arteriovenous fistulae, regulation of autonomic function, slowing the decline in GFR, changes in endothelial function, vascular conductance and venous compliance and inflammatory markers (IL-18, IL-10, IL-5, TNF-alfa vasopressin, F2-isopropane, NO2 and angiotensin 1-17) [22]-[28].

The aim of this text is to present the intervention protocol with strength training associated with the RFS method for people with stage 3 CKD and to report the benefits in terms of hemodynamics and personal satisfaction after 4 weeks of exposure to exercise.

2. Methos and materials

2.1. Type of study

The proposed intervention protocol is part of the research project “Chronic effects of strength training with blood flow restriction on glomerular function, functional capacity and perceived quality of life of people with chronic kidney disease” approved by the ethics committee of the Professor Alberto Antunes University Hospital of the Federal University of Alagoas (CEP-HUPAA/UFAL) under protocol number 7.159.681/2024. The study was registered on the Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry Platform (REBEC) under the number RBR-7bt6dxb.

2.2. Population and sample

The population was made up of adults and elderly people of both sexes with CKD. The sample consisted of people of both sexes, aged between 35 and 75 years, with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) between 59 and 30 ml/min/1.73m2 treated at the nephrology services of the Professor Alberto Antunes University Hospital (HUPAA).

The sample calculation was carried out using the UNESP-BAURU calculator (estastistica.bauru.usp.br/calculoamostral/ta_ic_proporcao.php), adopting a 95 % confidence interval and a sampling error of 5 %, with an estimated proportion of people with CKD prevalence with GFR between 59 and 30 ml/min/1.73m2 in the HUPAA urinary system service between January and July 2024, totaling the effective number of 197 patients, considering it as a finite population.

Thus, using a power of 0.8 as a measure, considering a significance level of 5 %, and an effect size of 0.25, to analyze 4 groups, taking 4 measurements in each of them, with a correlation rate between measurements of 0.5, a sample of 35 subjects was estimated. Estimating a sample loss, 5 participants were added, giving a final number of study members of 40 subjects.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

The study included people with CKD who lived in the city of Maceió and the metropolitan region of Alagoas, Brazil; signed a Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF); and did not have the following clinical conditions: people who do not have neurodegenerative or infectious diseases (HIV with detectable active viral load and systemic lupus erythematosus); symptomatic heart failure according to the New York Association Heart (NYAH) criteria; sepsis in the last 12 months; hepatitis C and B under treatment; coagulation dysfunction or signs of thrombophlebitis; surgery in the last 3 months; severe arrhythmia, angina or cerebrovascular or cardiovascular disease; pulmonary congestion or peripheral edema; previous surgery or vascular access in the upper limbs; participants with an Ankle Brachial Index (ABI) between 0.91 and 1.30.

Participants were excluded from the study if, after starting the intervention period, they were affected by any hypokinetic or osteoarticular disease or cardiovascular events; if they had medical recommendations to leave the study; if they did not attend more than 85 % of the sessions planned for the intervention; or if they had personal needs or wishes to withdraw from the research.

2.4. Randomization

The participants were allocated to 4 groups: 1) Low-load strength training associated with the blood flow restriction method (GRFS); 2) Low-load strength training (GBC); 3) High-load strength training (GAC); 4) No strength training.

The groups were matched on gender, activity level, stage 3 sub-classifications and different levels of quality of life and functional capacity.

2.5. Blood flow restriction method

The method of restricting blood flow consists of extending an external compression around the proximal region of the limbs (upper and lower) using pneumatic cuffs. During training, sufficient pressure is applied to restrict muscular venous return, usually in the range between 30 and 70 % of millimeters of mercury identified from the insonation pulse based on the measurement of systemic blood pressure. This measure also allows for the existence of blood bundles for muscular arterial inflow [29].

Compression can be performed continuously (without removing the cuff) or intermittently (with the cuff removed) after performing a series of each exercise. Thus, after removing the compression device, reperfusion is physiologically manifested, aimed at renewing and recovering muscle tissue (a product of reperfusion ischemia), responsible for an increase in blood supply with high metabolic concentrations [30].

In addition, the RFS method uses a low load, usually estimated at between 20-30 % of 1RM, which, due to the use of comprehension, allows similar responses to training with loads of between 70-80 % of 1RM. Normally, strength training protocols use 4 sets of 30-15-15-15 repetitions per exercise.

2.6. Intervention protocol

The physical intervention was carried out in the weight training room of the Institute of Physical Education and Sport (IEFE) of the Federal University of Alagoas (UFAL) between September 23 and October 19, 2024, corresponding to 12 sessions in 4 weeks.

The training sessions took place on 3 days a week, lasting 30 to 40 minutes in the morning and/or afternoon, and were designed by the researcher and collaborators. Although the participants’ training schedule was scheduled in advance, there was the possibility of changes due to medical commitments, clinical procedures, or the participants' personal commitments.

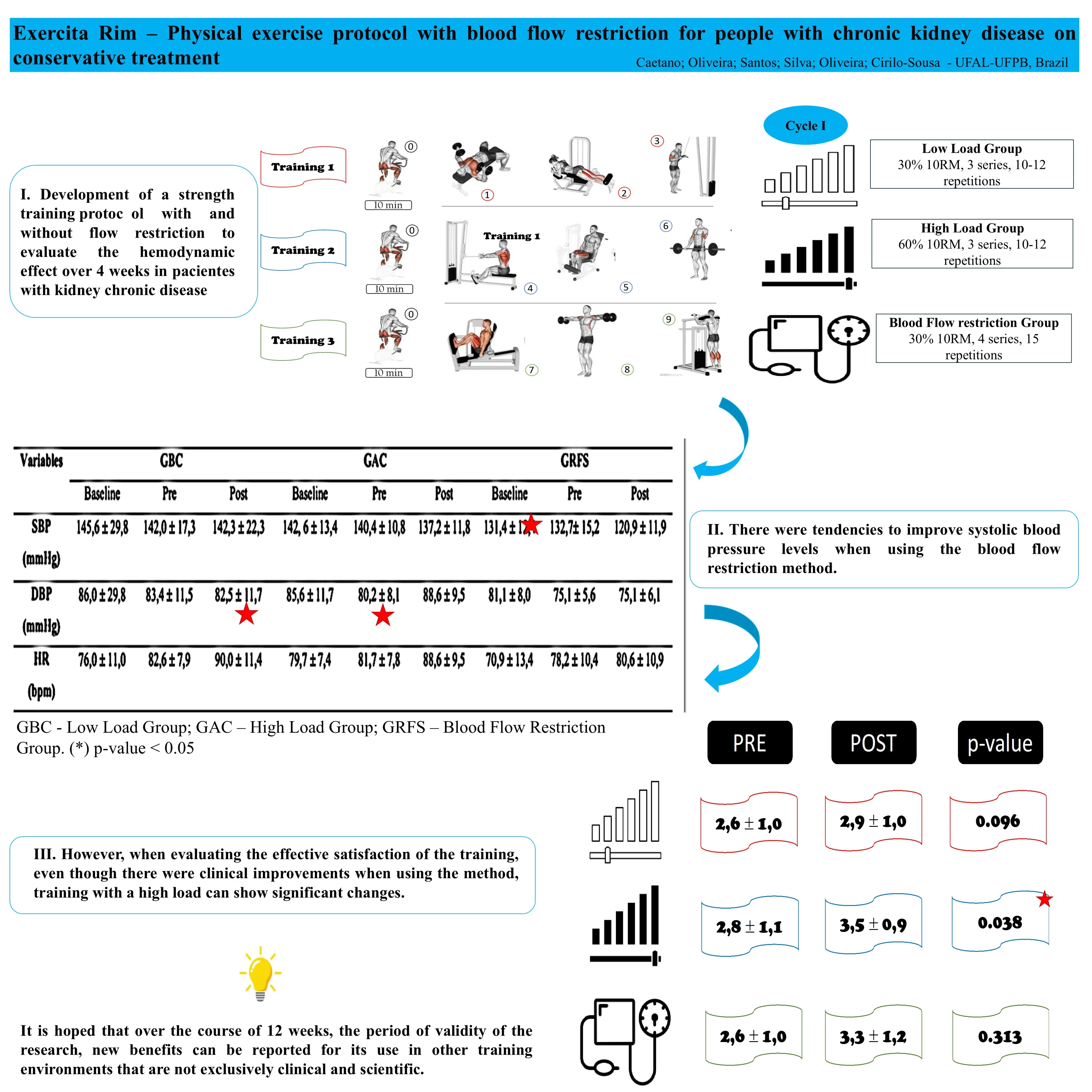

Fig. 1Proposed strength exercise training protocol for people with CKD-3. Source: (0) cycle ergometer; (1) bench press with dumbbells; (2): bilateral flexor table; (3) triceps on pulley with straight bar; (4) low row with straight bar; (5) bilateral extension chair; (6) barbell curl; (7) bilateral 45° Leg Press; (8) lateral raise with dumbbells; (9) standing calf raise on machine

The protocol consisted of 6 (six) exercises, namely: bench press with dumbbells, bilateral knee extension (extension chair), triceps on pulley with straight bar, seated row with straight bar, bilateral knee flexion (flexor table), barbell curl, hip flexion (45° leg press on machine), lateral raise with dumbbells and vertical calf raise on machine. The distribution of these exercises can be seen in Fig. 1.

In addition, before and after the training session, stretches were performed (unilateral elbow flexion behind the back, unilateral standing knee flexion; hip flexion with the hands; and hip flexion on the backrest) lasting 20 seconds each movement and then a warm-up on the cycle ergometer (model MS-160) for 10 minutes at a level 1 control intensity. One level will be added every 3 weeks of the protocol. However, there was no speed control.

The training protocol was designed in 4 progression cycles, as shown in Table 1. This text reports the results of this first cycle only.

Table 1Training progression cycles

Groups | Cycle I 1st to 3rd week | Cycle II 4th and 6th week | Cycle III 7th and 9th week | Cycle IV 10th and 12th week | ||||||||

Series | N rep. | Load (10RM) | Series | N rep. | Load (10RM) | Series | N rep. | Load (10RM) | Series | N rep. | Load (10RM) | |

GRFS | 4 | 15 | 30 % | 4 | 15 | 30 % | 4 | 15 | 30 % | 4 | 15 | 30 % |

GBC | 3 | 10-12 | 30 % | 3 | 10-12 | 35 % | 3 | 8-10 | 40 % | 3 | 10-12 | 40 % |

GAC | 3 | 10-12 | 60 % | 3 | 10-12 | 70 % | 3 | 8-10 | 80 % | 3 | 10-12 | 80 % |

The GRFS performed 4 sets of each exercise, with 15 repetitions and a load of 30 % 10RM. There was an adjustment to the blood flow restriction value at week 7 after a reassessment of the auscultatory pulse. The blood flow restriction was made conditionally, with 50 % of the arterial occlusion pressure (AOP)/insonation pressure and performed continuously. The GBC in the 1st cycle (1st to 3rd week) performed exercises in 3 sets of 10-12 repetitions, with 30 % 10RM. The GAC in the 1st cycle (1st to 3rd week) performed exercises in 3 sets of 10-12 repetitions with 60 % 10RM.

In all groups, after the 6th week there will be a new evaluation of the 10RM test to adjust the load to be applied from the 7th week onwards.

In addition, in the intervention groups, the exercises were timed using a digital metronome model DIGIPOM (version 1.2.0), emitting digital sound in the indigo theme, with a rhythm of 2 beats in 2/4-time, equivalent to 48 beats per minute.

BP and HR were measured before and after each session throughout the intervention period.

During the intervention session, the effects of the intensity of the exercise on the patient were measured using the Borg Subjective Perception of Effort scale (PSE-BORG). The instrument consists of a scale that serves as a tool to identify and measure the sensation of effort perceived during a physical task [31]. The adapted BORG scale is divided into 5 indices: Zone 1 – weak (< 70 % of effort); Zone 2 – moderate (70-80 % of effort); Zone 3 – moderate to intense (80-85 % of effort); Zone 4 – intense/very intense (85-90 % of effort); Zone 5 – exhaustion (> 90 % of effort).

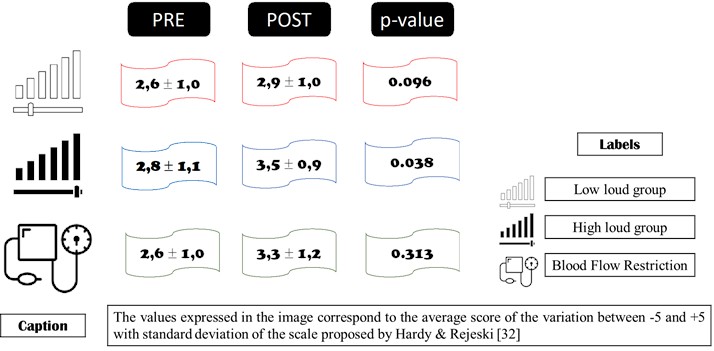

Finally, the scale of affective feelings for physical exercise was measured, as proposed by Hardy & Rejeski [32]. The scale identifies the participants' state on a continuum ranging from –5 (very bad), –4, –3 (bad), –2, –1 (fairly bad), 0 (neutral), +1 (fairly good), +2, +3 (good), +4 to +5 (very good). The scale was applied to the participants by oral questioning during each day of training, always before the start of the protocol and after the end of the session of all the exercises proposed for the day. The final result was expressed as the average (before and after) of all the sessions carried out by the participants over four weeks.

2.7. Measures evaluated

In the study is evaluating behavioral, morphological, functional capacity, blood and urinary measurements.

– Behavioral measures: semi-structured questionnaire with questions regarding age, gender, level of education, skin color, level of education, marital status, use of tobacco, alcohol and other drugs, associated diseases and level of CKD stage; level of physical activity with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [33]; level of sarcopenia, SARC-F [34]; perceived discomfort questionnaire [35]; perceived quality of life SF-36 [36]; level of fatigue, Piper scale [37]; level of mood, POMS [38].

– Morphological measurements: weight, height, body mass index (BMI), waist, hip, arm, leg and calf circumferences, body composition (tetrapolar bioimpedance).

– Functional capacity measures: hand pressure dynamometry; 6-minute walk test; sit and stand test; forearm flexion test; sit and reach test; Time Up and Go (TUG) test; and reach behind the back test [39], [40].

– Neuromuscular measurements: 10-repetition maximum (10RM) test, validated 1-repetition maximum (1RM) test protocol [41]-[43] for the exercises bench press with dumbbells, bilateral knee extension (extension chair), pulley triceps with straight bar, seated row with straight bar, bilateral knee flexion (flexor table), barbell curl, hip flexion (45° leg press on the machine), lateral raise with dumbbells and vertical calf raise on the machine.

– Blood and urine measurements: non-fasting glycemia, urinalysis (color index, urobilinogen, glucose, ketone bodies, bilirubin, protein, nitrite, pH, hemoglobin and leukocytes), renal (serum creatinine, Cystatin-C, microalbuminuria), muscle damage (CK and Aldolase), thrombotic risk (D-dimer) and cellular inflammation (IL-6) were carried out by private laboratory DILAB (Maceió, Alagoas, Brazil).

These measurements were taken one week before the start of the intervention with the training protocol and will be repeated in the week immediately after the end of the entire study, scheduled for 12 weeks.

As this text aims to present only the training protocol developed for this population, as well as its possible hemodynamic effects after 4 weeks of use, the data referring to behavioral, morphological, functional capacity, blood and urinary measurements will not be discussed in this article and will be saved for a future opportunity. The intention of revealing the existence of these measures was only to demonstrate the other monitoring that is being carried out for the safety and follow-up of the participants.

3. Results and Discussion

The intervention involved 40 adult and elderly individuals with stage 3 CKD undergoing conservative treatment at a high-complexity hospital in the city of Maceió/Alagoas, Brazil. Of these, 21 were men (52.5 %) and 19 were women (47.5 %) with an average age of 58 ± 8.9 years. In terms of social aspects, the majority were self-classified as brown (45 %), married (62.5 %), not working (65 %) and with low levels of schooling (57.5 %).

In terms of health behaviors and lifestyle, the participants were hypertensive (87.5 %), non-diabetic (62.5 %), non-users of tobacco (70 %) and alcohol (52.5 %) and reported having no other associated disease (55 %). In terms of physical activity levels, the group had low levels of physical activity and were classified as insufficiently active and/or sedentary (60 %).

Attendance at training sessions was 80.8 % for GBC, 76.9 % for GAC and 91.7 % for GRFS. The reasons for absence ranged from medical appointments, micro-surgical procedures, pain, tiredness, and lack of money to pay for travel to the intervention environment. Table 2 shows the results of the means and standard deviations of the hemodynamic measurements at baseline, before and after the intervention.

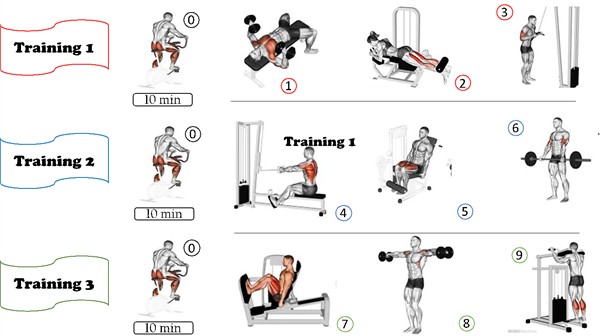

Table 2Hemodynamic measurements at baseline, before and after the physical exercise protocol for patients with CKD-3 in 12 sessions over 4 weeks

Variables | GBC | GAC | GRFS | ||||||

Baseline | Pre | Post | Baseline | Pre | Post | Baseline | Pre | Post | |

SBP (mmHg) | 146,6 ± 29,8 | 142,0 ± 17,3 | 142,3 ± 22,3 | 142,6 ± 13,4 | 140,4 ± 10,8 | 137,2 ± 11,8 | 131,4 ± 12,4 | 132,7 ± 15,2 | 120,9± 11,9 |

DBP (mmHg) | 86,0 ± 29,8 | 83,4 ± 11,5 | 82,5 ± 11,7 | 85,6 ± 11,7 | 89,2 ± 8,1 | 88,6 ± 9,5 | 81,1 ± 8,0 | 75,1 ± 5,6 | 75,1± 6,1 |

HR (bpm) | 76,0 ± 11,0 | 82,6 ± 7,9 | 90,0 ± 11,4 | 79,7 ± 7,4 | 81,7 ± 7,8 | 88,6 ± 9,5 | 70,9 ± 13,4 | 78,2 ± 10,4 | 80,6 ± 10,9 |

Source: authors, 2024. Legend: SBP – Systolic Blood Pressure; DBP – Diastolic Blood Pressure; HR – Heart Rate; GBC – Low Load Group; GAC – High Load Group; GRFS – Blood Flow Restriction Group | |||||||||

For SBP, the GRFS group showed the greatest drop in blood pressure levels from baseline to after the exercise protocol (11.9 mmHg), although this was not statistically significant ( 0.101).

For diastolic blood pressure, the GRFS group had the biggest drop (6.0 mmHg), but with only a trend towards a significant difference (0.082). However, when the measurements are compared only over the 4-week intervention period, as shown in Table 3, a statistical difference can be seen for SBP in the GRFS (0.034) and HR for the GBC (0.006) and GAC (0.034).

Table 3Comparison of hemodynamic measurements before and after the exercise protocol for patients with CKD-3 in 12 sessions over 4 weeks (paired T-test) (N= 30)

Variables | GBC | GAC | GRFS | |||

p-value | Cohen’s d | p-value | Cohen’s d | p-value | Cohen’s d | |

SBP (mmHg) | 0.922 | –0.032 | 0.249 | 0.390 | 0.034* | 0.791 |

DBP (mmHg) | 0.556 | 0.193 | 0.512 | 0.216 | 0.824 | 0.072 |

HR (bpm) | 0.006* | –1.128 | 0.034* | –0.782 | 0.099 | –0.582 |

Source: authors, 2024. Legend: SBP – Systolic Blood Pressure; DBP – Diastolic Blood Pressure; GBC – Low Load Group; GAC – High Load Group; GRFS – Blood Flow Restriction Group. (*) p-value < 0.05 | ||||||

Finally, heart rate increased in all groups. The GBC showed the greatest increase (6.6 bpm), but in all groups the data revealed a statistically significant difference: GBC (0.014), GAC (0.001) and GRFS (0.037).

When we looked at satisfaction (Fig. 2) after the intervention protocol, the GAC showed a statistically significant difference (0.038) in the improvement in perceived satisfaction. However, it is worth mentioning that all groups showed an increase in affective satisfaction with the proposed training.

As for the effects after the training sessions, the blood flow restriction group reported a reduction in swelling, localized pain, and an improvement in physical disposition as positive results. On the other hand, cramps, tingling sensations and pressure behind the neck were reported as adverse effects.

Fig. 2Affective satisfaction with the physical exercise protocol in people with CKD-3 in 12 sessions over 4 weeks. Source: authors, 2024.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, and systemic arterial hypertension (SAH) are considered underlying diseases for the onset and progression of CKD [44]. There is already evidence that an increase in blood pressure is associated with a decrease in the number of nephrons because of fewer renal glomeruli [45]. The arterial system is made up of high-pressure tubes that transport substances, including O2, to all parts of the body. Thus, blood pressure is nothing more than ventricular contraction from the combined effects of arterial blood flow per minute as opposed to peripheral vascular resistance [46]. When there is a stiffening of the vessels due to debris in the arterial wall which leads to an increase in peripheral flow resistance because of nervous hyperactivity and/or alterations in renal function, this characterizes the existence of SAH. Therefore, due to the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system regulated by the kidney glands, SAH ends up having an immediate impact through morphological and debilitating changes in the kidneys' glomerular filtration activities.

One of the main measures in conservative (non-dialytic) treatment for people with CKD is the use of drugs to control blood pressure levels (beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers), as well as the reduction and/or elimination of smoking and the introduction of regular physical activity, as a non-pharmacological strategy to keep SAH conditions somewhat under control. For stage 3, which is the subject of this analysis, non-diabetics should have blood pressure levels between 140/90 mmHg and diabetics between 130/80 mmHg [47].

Regular physical activity promotes an increase in endothelial function, leading to a decrease in cellular inflammation and an increase in pro-inflammatory substances in the adipocyte, as well as a decrease in oxidative stress and intestinal dysbiosis [48]. In terms of SAH, the responses will be linked to intensity, but in general, they corroborate an increase in vasodilation in the muscles being trained, providing a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance [46]. However, the prevalence of regular physical activity practice at the levels recommended by the WHO and the Brazilian Guide to Physical Activity Practice [9] - above 150 minutes per week of aerobic activity - is still low in this population, at around 60-70 %, regardless of the stage they are at [49]-[51].

In any case, intervention studies with aerobic exercise and strength exercises have been divided in terms of results, although few have specifically evaluated this variable in patients undergoing non-dialysis treatment. While some studies have shown low evidence in blood pressure levels, but good results in increasing functional capacity and fasting glycemia [8], [52]; others have shown a decrease in SBP and DBP, and satisfactory changes in HR [53]. In addition, the variability of the types of intervention – high-intensity interval training, electrical stimulation of muscles, association with nutritional supplementation and use of the RFS method – has proved to be additional strategies in the incorporation of physical exercise in this population [11]

For strength training associated with BFR, few studies have looked at hemodynamic changes as primary outcomes. In association with strength training, some findings indicate that there are no changes in peak SBP when investigating increases in vessel diameter [28]; a decrease in blood pressure, redox balance and the bioavailability of nitric oxide, an essential substance for regulating vasodilation and vasoconstriction [25]; and an increased risk of D-dimer levels (> 500 ng/mL) after 4 hours of exercise in people on hemodialysis, increasing the chances of thrombosis, which is extremely associated with peripheral vascular resistance [24]. In the use of aerobic exercise, no risks of vascular stress and harmful pressure changes were found with RFS [54].

Thus, there is a need to expand research into hemodynamic responses to exercise training associated with RFS, so that aspects related to intensity, RFS measurements and exercise frequency can build safer parameters for the CKD population. Logically, the short period of analysis of this protocol is a limitation for analyzing the results in a broader way, but it may indicate promising results to come from a longer-term intervention.

4. Conclusions

After 4 weeks of intervention with a strength training protocol, there were tendencies to improve systolic blood pressure levels when using the blood flow restriction method. However, when evaluating the effective satisfaction of the training, even though there were clinical improvements when using the method, training with a high load can show significant changes.

It is hoped that over the course of 12 weeks, the period of validity of the research, new benefits can be reported for its use in other training environments that are not exclusively clinical and scientific.

References

-

D. C. Nieman, Exercise and Health: Exercise Testing and Prescription. (in Portuguese), São Paulo: Manole, 2011.

-

Vieira and A. A. V., Physical Exercise and its Benefits in the Treatment of Diseases. (in Portuguese), Rio de Janeiro: Atheneu, 2015.

-

V. Raso, J. M. A. Greve, and M. D. Polito, Pollock: Clinical Physiology of Exercise. (in Portuguese), São Paulo: Manole, 2013.

-

“KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the avaluation and management of chronic kidney disease,” Kidney International Supplements, Vol. 105, No. 45, 2024.

-

O. M. Akchurin, “Chronic kidney disease and dietary measures to improve outcomes,” Pediatric Clinics of North America, Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. 247–267, Feb. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2018.09.007

-

“Chronic kidney disease: diagnosis and prevention,” (in Portuguese), Brazilian Society of Nephrology, Apr. 2020.

-

“What does conservative treatment of chronic kidney disease mean?” Brazilian Society of Nephrology, Dec. 2021, https://www.sbn.org.br/orientacoes-e-tratamentos/tratamentos/tratamento-conservador/.

-

F. Villanego et al., “Impact of physical exercise in patients with chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis,” Nefrología, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 237–252, May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nefro.2020.01.002

-

“Physical Activity Guide for the Brazilian Population,” (in Portuguese), The Ministry of Health, Brazil, 2021.

-

F. C. Bull et al., “World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour,” British Journal of Sports Medicine, Vol. 54, No. 24, pp. 1451–1462, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

-

T. J. Wilkinson, M. Mcadams-Demarco, P. N. Bennett, and K. Wilund, “Advances in exercise therapy in predialysis chronic kidney disease, hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation,” Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension, Vol. 29, No. 5, pp. 471–479, Jul. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1097/mnh.0000000000000627

-

F. Mallamaci, A. Pisano, and G. Tripepi, “Physical activity in chronic kidney disease and the EXerCise introduction to enhance trial,” Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Vol. 35, Mar. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa012

-

H. Noor, J. Reid, and A. Slee, “Resistance exercise and nutritional interventions for augmenting sarcopenia outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a narrative review,” Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, Vol. 12, No. 6, pp. 1621–1640, Sep. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12791

-

H. C. Dreyer, S. Fujita, J. G. Cadenas, D. L. Chinkes, E. Volpi, and B. B. Rasmussen, “Resistance exercise increases AMPK activity and reduces 4E‐BP1 phosphorylation and protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle,” The Journal of Physiology, Vol. 576, No. 2, pp. 613–624, Oct. 2006, https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113175

-

T. M. Manini and B. C. Clark, “Blood flow restricted exercise and skeletal muscle health,” Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 78–85, Apr. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1097/jes.0b013e31819c2e5c

-

M. S. Cirilo-Sousa, A. F. P. Caetano, C. L. M. P. França, J. A. Oliveira, P. A. M. Dantas, and P. H. M. Lucena, “Blood flow restriction: clinical aspects, evidence, and scientific innovation in the use of the method,” (in Portuguese) in Doing and Thinking about Science in Physical Education, Recife: EDUPE, 2025, pp. 473–496.

-

N. Ishii, H. Madarame, K. Odagiri, M. Naganuma, and K. Shinoda, “Circuit training without external load induces hypertrophy in lower-limb muscles when combined with moderate venous occlusion,” International Journal of KAATSU Training Research, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 24–28, Jan. 2005, https://doi.org/10.3806/ijktr.1.24

-

G. C. Laurentino et al., “Strength training with blood flow restriction diminishes myostatin gene expression,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 406–412, Mar. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e318233b4bc

-

M. Krzysztofik et al., “Resistance training with blood flow restriction and ocular health: a brief review,” Journal of Clinical Medicine, Vol. 11, No. 16, p. 4881, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164881

-

J. P. Loenneke et al., “Effects of cuff width on arterial occlusion: implications for blood flow restricted exercise,” European Journal of Applied Physiology, Vol. 112, No. 8, pp. 2903–2912, Dec. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-2266-8

-

M. L. Sousa, F. P. Silva, J. C. G. Silva, A. F. P. Caetano, H. L. Miranda, and M. S. Cirilo-Sousa, “Analysis of the effects of physical training with blood flow restriction on hormonal, biochemical, and hematological levels: a systematic review,” (in Portuguese), Revista de Medicina (Ribeirão Preto), 2025.

-

R. Rus, R. Ponikvar, R. B. Kenda, and J. Buturović‐Ponikvar, “Effects of handgrip training and intermittent compression of upper arm veins on forearm vessels in patients with end‐stage renal failure,” Therapeutic Apheresis and Dialysis, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 241–244, Jun. 2005, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1774-9987.2005.00263.x

-

N. Rolnick, I. V. Sousa Neto, E. F. Fonseca, R. V. P. Neves, T. S. Rosa, and D. C. Nascimento., “Potential implications of blood flow restriction exercise on patients with chronic kidney disease: a brief review,” Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 81–95, Apr. 2022, https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.2244082.041

-

H. L. Corrêa, L. A. Deus, D. C. Nascimento, N. Rolnick, R. V. P. Neves, and A. L. Reis, “Concerns about the application of resistance exercise with blood-flow restriction and thrombosis risk in hemodialysis patients,” Journal of Sport and Health Science, Vol. 13, pp. 548–558, 2024, https://doi.org/1016/j.jshs.2024.02.006

-

H. L. Corrêa et al., “Low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction prevent renal function decline: The role of the redox balance, angiotensin 1-7 and vasopressin,” Physiology and Behavior, Vol. 230, p. 113295, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113295

-

L. A. Deus, R. V. P. Neves, H. L. Corrêa, A. L. Reis, F. S. Honorato, and V. L. Silva, “Improving the prognosis of renal patients: the effects of blood flow-restricted resistance training on redox balance and cardiac autonomic function,” Experimental Physiology, Vol. 106, pp. 1099–1109, 2021.

-

I. B. Silva, J. B. N. Barbosa, A. X. P. Araújo, and P. E. M. Marinho, “Effect of an exercise program with blood flow restriction on the muscular strength of patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized clinical trial,” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, Vol. 28, pp. 187–192, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2021.06.022

-

J. B. Barbosa et al., “Does blood flow restriction training increase the diameter of forearm vessels in chronic kidney disease patients? A randomized clinical trial,” The Journal of Vascular Access, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 626–633, Apr. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/1129729818768179

-

M. S. Cirilo-Sousa and G. Rodrigues Neto, Blood Flow Restriction Physical Training Methodology. (in Portuguese), João Pessoa: Editora Ideia, 2018.

-

Y. Takarada, H. Takazawa, and N. Ishii, “Applications of vascular occlusion diminish disuse atrophy of knee extensor muscles,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, Vol. 32, No. 12, pp. 2035–2039, Dec. 2000, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200012000-00011

-

A. C. E. Silva et al., “Borg and OMNI scales in exercise prescription on a cycle ergometer,” (in Portuguese), Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria e Desempenho Humano, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 117–123, Feb. 2011, https://doi.org/10.5007/1980-0037.2011v13n2p117

-

C. J. Hardy and W. J. Rejeski, “Not what, but how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise,” Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 304–317, Sep. 1989, https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.11.3.304

-

S. Matsudo, “International physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ): validity and reproducibility study in Brazil,” (in Portuguese), Atividade Física and Saúde, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 6–18, 2001.

-

A. J. Cruz-Jentoft et al., “Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis,” Age and Ageing, Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 16–31, Jan. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169

-

I. Kuorinka et al., “Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms,” Applied Ergonomics, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 233–237, Sep. 1987, https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-x

-

R. M. Ciconelli, M. B. Ferraz, W. Santos, I. Meinão, and M. R. Quaresma, “Brazilian-Portuguese version of the SF-36. A reliable and valid quality of life outcome measure,” (in Portuguese), Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 143–150, 1999.

-

J. C. Bahia, C. M. Lima, M. M. Oliveira, J. V. Guimarães, M. O. Santos, and D. D. C. F. Mota, “Fatigue in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy,” (in Portuguese), Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia, Vol. 65, No. 2, Oct. 2019, https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.rbc.2019v65n2.89

-

D. Mcnair, M. Lorr, and L. Droppleman, Manual for the Profile of Mood States. San Diego: Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1971.

-

R. E. Rikli and C. J. Jones, “Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults,” Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 129–161, Apr. 1999, https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.7.2.129

-

R. E. Rikli and C. J. Jones, “Functional fitness normative scores for community-residing older adults, ages 60-94,” Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 162–181, Apr. 1999, https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.7.2.162

-

E. P. L. Vieira, A. D. V. Deserto, E. D. Alves Júnior, and J. L. Gurgel, “Reproducibility of the 10-rep max test in older women,” (in Portuguese), Acta Fisiátrica, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 184–189, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2317-0190.v29i3a182604

-

E. P. L. Vieira, A. D. V. Deserto, E. D. Alves Junior, and J. L. Gurgel, “Reproducibility of the 10 RM strength test in young female university students,” (in Portuguese), RBPFEX – Revista Brasileira de Prescrição e Fisiologia do Exercício, Vol. 14, No. 94, pp. 1014–1023, 2020, https://doi.org/https://www.rbpfex.com.br/index.php/rbpfex/article/view/2325

-

R. M. R. Dias, A. Avelar, A. L. Menêses, E. P. Salvador, D. R. P. Silva, and E. S. Cyrino, “Safety, reproducibility, confounding factors, and applicability of 1-RM tests,” (in Portuguese), Motriz, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 231–42, 2013.

-

L. K. Aguiar, R. R. Prado, A. Gazzinelli, and D. C. Malta, “Factors associated with chronic kidney disease: epidemiological survey from the national health survey,” (in Portuguese), Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, Vol. 23, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720200044

-

G. Keller, G. Zimmer, G. Mall, E. Ritz, and K. Amann, “Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 348, No. 2, pp. 101–108, Jan. 2003, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa020549

-

W. D. Mcardle, F. I. Katch, and V. L. Katch, Exercise Physiology: Nutrition, Energy, and Human Performance. (in Portuguese), Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 2017.

-

“Clinical guidelines for the care of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the Unified Health System,” (in Portuguese), Ministério da Saúde, Brasília, 2014.

-

D. Pongrac Barlovic, H. Tikkanen-Dolenc, and P.-H. Groop, “Physical activity in the prevention of development and progression of kidney disease in type 1 diabetes,” Current Diabetes Reports, Vol. 19, No. 7, pp. 40–48, May 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1157-y

-

A. F. P. Caetano, F. A. N. Alves, K. M. S. França, A. V. F. Gomes, and J. C. F. Santos, “Stage of chronic kidney disease and its associations with physical activity level, quality of life, and nutritional profile,” (in Portuguese), Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física e Saúde, Vol. 27, p. e0253, 2022.

-

A. F. P. Caetano, F. A. N. Alves, K. M. D. S. França, A. V. F. Gomes, M. J. C. Oliveira, and J. C. F. Dos Santos, “Level of physical activity in chronic kidney patients and correlations with nutritional profile and quality of life,” (in Portuguese), Revista Contexto and Saúde, Vol. 23, No. 47, p. e12984, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.21527/2176-7114.2023.47.12984

-

A. F. P. Caetano, “Physical activity and chronic kidney disease: observational studies and experience reports,” (in Portuguese), Home Editora, Belém, Feb. 2024, https://doi.org/10.46898/rfb.d9cada0f-9fec-422f-84cd-de4fb95d5ca9

-

F. C. Barcellos et al., “Exercise in patients with hypertension and chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial,” Journal of Human Hypertension, Vol. 32, No. 6, pp. 397–407, Apr. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-018-0055-0

-

T. A. Ikizler et al., “Metabolic effects of diet and exercise in patients with moderate to severe CKD: a randomized clinical trial,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 250–259, Oct. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2017010020

-

M. J. Clarkson, C. Brumby, S. F. Fraser, L. P. McMahon, P. N. Bennett, and S. A. Warmington, “Hemodynamic and perceptual responses to blood flow-restricted exercise among patients undergoing dialysis,” American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology, Vol. 318, No. 3, pp. F843–F850, Mar. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00576.2019

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The people with chronic kidney disease who agreed to participate in this study; to Prof. Dr. Gustavo Araújo for supporting the provision of space for the investigation; and to the Federal University of Alagoas for granting study leave to make the research viable.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Antonio Filipe Pereira Caetano: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation. methodology, project administration, resources, validation, visualization, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing. Janyeliton Alencar De Oliveira: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing-original draft preparation. Camila Fernandes Pontes Dos Santos: investigation, writing-original draft preparation. Amaro Wellington Da Silva: formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft preparation. Michelle Jacintha Cavalcante Oliveira: investigation. Maria Do Socorro Cirilo Sousa: conceptualization, investigation, supervision, writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The proposed intervention protocol is part of the research project “Chronic effects of strength training with blood flow restriction on glomerular function, functional capacity and perceived quality of life of people with chronic kidney disease” approved by the ethics committee of the Professor Alberto Antunes University Hospital of the Federal University of Alagoas (CEP-HUPAA/UFAL) under protocol number 7.159.681/2024.

The study was registered on the Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry Platform (REBEC) under the number RBR-7bt6dxb.