Abstract

This study systematically investigates the efficacy of nano-silica (NS) and nano-alumina (NA) in mitigating the detrimental effects of low-temperature curing (5 °C) on concrete performance through a multi-scale experimental approach. Macroscopic tests revealed that an incorporation of 2 % NS or 1 % NA not only optimized compressive strength under standard curing but also effectively counteracted the strength reduction induced by low-temperature curing. Microstructural analysis using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), and Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) revealed that both nanomaterials improve performance by densifying the pore system, speeding up the hydration process, and encouraging the generation of more calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) at the expense of calcium hydroxide (CH). Notably, 1 % NA yielded superior microstructural improvement compared to 2 % NS, achieving comparable mechanical enhancement at a 50 % lower dosage. The findings indicate that nano-alumina, owing to its higher efficiency and cost-effectiveness, presents an ideal admixture for producing durable concrete in cold-region applications.

Highlights

- Nano-Alumina (NA) achieves comparable mechanical enhancement at half the dosage (1%) of Nano-Silica (2%), demonstrating superior efficiency.

- Both 2% NS and 1% NA significantly mitigate the strength loss of concrete cured at 5°C, with NA showing near-complete performance retention.

- 1% NA induces exceptional pore structure refinement, reducing total porosity by 44% (to 7.5%), far exceeding the effect of 2% NS.

- NA excels in early-age strength via enhanced nucleation, while NS provides sustained strength gain through prolonged pozzolanic reactions.

- The findings position nano-alumina as a transformative, cost-effective admixture for enabling year-round concrete placement in cold regions without thermal curing.

1. Introduction

To overcome the performance limitations of conventional concrete in sustainable construction, this study explores engineered composite materials enhanced through nanotechnology. As a fundamental material in modern infrastructure, concrete demands continuous advancement via innovative additives to meet growing demands for sustainability and energy efficiency. Breakthroughs in nanomaterial synthesis have facilitated the mass production of functional particles such as nano-silica (NS) and nano-alumina (NA), which exhibit exceptional potential for microstructural optimization through pore-filling effects and pozzolanic reactions [1-3]. Extensive research [4-7] demonstrates that nanoparticle incorporation increases matrix density by 18-25 % via physical pore refinement and chemical C-S-H gel formation, significantly enhancing mechanical strength and durability under standard curing conditions (20±2 °C). Recent comprehensive reviews, such as by Adesina [8], have further systematized the mechanisms of various nanomaterials, including NS and NA, highlighting their role in developing next-generation sustainable infrastructure.

China’s cold regions present particularly challenging environments for civil engineering projects, characterized by two key climatic parameters: (1) monthly mean temperatures of –10 to 0 °C during the coldest month, and (2) annual periods of 90-145 days with mean daily temperatures ≤ 5 °C. These conditions create widespread permafrost and seasonally frozen ground zones, where persistent suboptimal thermal conditions significantly impact construction materials. For experimental purposes, we established three thermal regimes: subzero (< 0 °C), low-temperature (0-10 °C), and ambient (10-25 °C) conditions. The selection of 5 °C as our experimental threshold aligns with internationally recognized standards for construction materials in cold climates [9, 10]. Low-temperature conditions markedly deteriorate concrete performance by slowing early-age hydration kinetics and impairing mechanical strength development [11-13]. Additionally, such conditions exacerbate workability issues, elevate cracking susceptibility, and increase electric flux and chloride permeability [14-19]. These adverse effects extend to modified concrete systems. For example, silica fume – incorporated cementitious composites (10 % dosage) exhibit reduced compressive strength under low-temperature curing [20, 21]. while limestone powder-modified cementitious materials demonstrate some strength enhancement under similar conditions [22]. The accurate prediction and optimization of material behavior in such demanding environments requires advanced computational approaches [23-26].

Previous research has extensively explored the hydration behavior of cement-based materials, including those incorporating nanomaterials, under standard curing conditions [27-29]. Studies have shown that the addition of various metal oxide nanoparticles – for instance, SiO2, TiO2, ZrO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, and Fe3O4 – can markedly improve the performance of concrete when cured at ambient temperatures [3, 30-33]. While our previous research [34, 35] confirmed the performance enhancement of SiO2 and Al2O3 nanoparticles in concrete under standard curing conditions, their effectiveness in low-temperature environments requires further investigation. Although preliminary studies like Zhang et al [36] have begun to explore the acceleration of hydration kinetics by NS at low temperatures, a systematic and comparative investigation into the synergistic effects and efficiency of both NS and NA under prolonged low-temperature curing (5 °C) is still lacking. Furthermore, the application of multi-scale modeling approaches [37] to understand these phenomena remains an open area of research. Existing studies provide preliminary evidence of this potential: Wang et al. [38] observed that nano-silica accelerates the hydration kinetics in cement paste at reduced temperatures, triggering immediate transition to the acceleration phase while bypassing the typical induction period. This process generates substantial ettringite and C-S-H gel formation during early hydration, resulting in microstructural refinement that compensates for cold-weather strength reduction.

However, a critical challenge in harnessing the full potential of nanomaterials is their inherent tendency to agglomerate due to high surface energy and van der Waals forces. This agglomeration can severely counteract the benefits of nano-reinforcement by creating weak points and inhomogeneities within the cement matrix, ultimately compromising the mechanical properties and durability of the composite. To mitigate this issue and ensure material consistency, effective dispersion strategies are paramount. These typically include physical methods, such as optimized ultrasonic dispersion to break apart agglomerates, and chemical approaches, such as the use of surfactants or surface treatments to improve nanoparticle stability in suspensions. The efficacy of these dispersion protocols, particularly under the constrained kinetics of low-temperature curing, requires thorough investigation to ensure uniform distribution and maximal performance enhancement.

While NS and NA have demonstrated significant improvements in concrete performance under standard curing conditions, their effectiveness in low-temperature environments remains insufficiently explored. This study presents a systematic investigation of nano-modified concrete cured at 5 °C, with comprehensive evaluation of: (1) mechanical performance, (2) microstructural evolution, and (3) hydration product formation. The findings provide critical data to support the application of these nanomaterials in cold-region construction while advancing fundamental understanding of their low-temperature behavior.

The novelty of this research lies in its direct comparative assessment of NS and NA efficiency under prolonged low-temperature curing, unequivocally identifying nano-alumina as the superior modifier due to its ability to achieve equivalent mechanical enhancement at a 50 % lower dosage – a finding with significant practical and economic implications for cold-region construction.

This study systematically investigates the efficacy of nano-silica (NS) and nano-alumina (NA) in mitigating the detrimental effects of low-temperature curing (5 °C) on concrete performance through a multi-scale experimental approach. The findings not only advance the fundamental understanding of nanomaterial behaviors in cementitious systems under constrained thermal conditions but also provide practical solutions for durable concrete production in cold-region construction, which aligns perfectly with the journal’s scope on sustainable infrastructure and innovative construction materials.

2. Experimental program

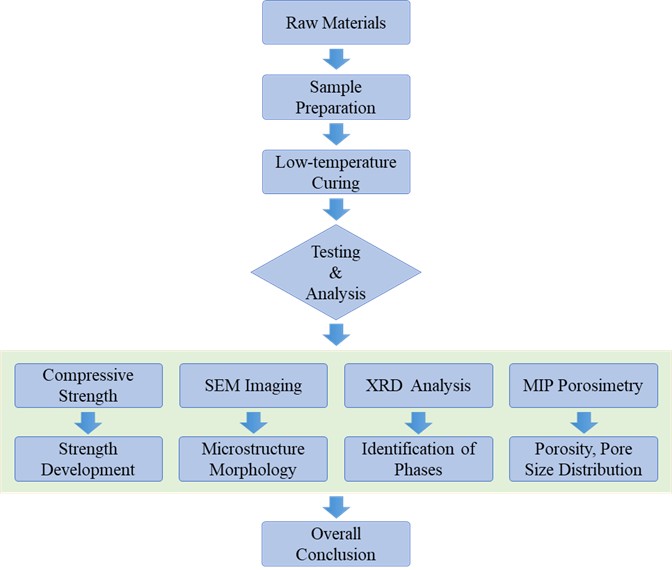

A series of experimental tests were conducted to evaluate the mechanical properties and microstructural characteristics of the cement-based materials, with the overall procedure outlined in the flowchart presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1Graphical abstract of the experimental design

2.1. Raw materials

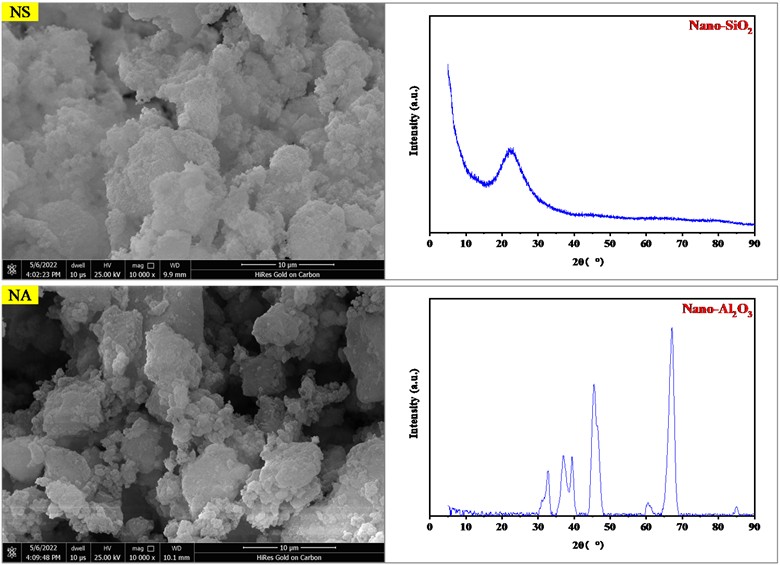

The P.O 42.5 ordinary Portland cement used in this study was supplied by Gansu Qilianshan Cement Group and conforms to the Chinese national standard GB 175-2007 [39]; its chemical composition is provided in Table 1. Fine and coarse aggregates consisted of natural river sand (maximum size < 4.75 mm, bulk density of 2.69 g/cm3, silt content 1.0 %) and crushed stone (particle size 5-20 mm, apparent density 2.85 g/cm3, clay content 0.6 %), respectively, both complying with specification JGJ 52-2006 [40]. A polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer with a water reduction rate of 25 % was added at a dosage of 1 % by weight of the cementitious materials. NS and NA with particle sizes less than 20 nm were obtained from Suzhou Yuante New Material Co., Ltd, China. The characterization data for these nanomaterials are presented in Fig. 2 and Table 2.

Table 1Chemical component of cement.

Chemical material | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | K2O | TiO2 | SO3 | Loss | |

Mass ratio (%) | 69.89 | 17.30 | 3.14 | 3.76 | 2.09 | 0.64 | 0.18 | 2.25 | 2.78 |

Table 2Properties of NS and NA.

Item | Purity | Specific surface area | Diameter | Density |

NS | 99.9 % | 220±20 m2/g | 20 nm | 0.10 g/cm3 |

NA | 99.9 % | 160±20 m2/g | 20 nm | 0.10 g/cm3 |

Fig. 2SEM micrographs and XRD patterns of NS and NA

2.2. Mixture proportions

Table 3 outlines the concrete mixed proportions designed with a constant water-binder ratio (/ = 0.4). NS or NA was incorporated as partial cement replacement at levels of 0 % (OPC control group), 1 % (designated as NS1 or NA1), 2 % (NS2 or NA2), and 3 % (NS3 or NA3). All mixes included 1 % superplasticizer by weight of the cementitious materials. Corresponding mortar specimens were prepared using identical proportions without aggregates, while paste samples (/ = 0.4) included OPC (0 %), NS2 (2 % NS), and NA1 (1 % NA) formulations for comparative analysis.

Table 3Mix proportion of concrete (kg/m3)

Sample | W/b | Cement | NS/NA | Water reducer | Sand | Aggregate |

OPC | 0.4 | 440.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 678.0 | 1106.0 |

NS1/NA1 | 0.4 | 435.6 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 678.0 | 1106.0 |

NS2/NA2 | 0.4 | 431.2 | 8.8 | 4.4 | 678.0 | 1106.0 |

NS3/NA3 | 0.4 | 426.8 | 13.2 | 4.4 | 678.0 | 1106.0 |

2.3. Sample preparation

The experimental procedure followed three key phases: (1) Mixture preparation began by dissolving the superplasticizer in water (10 min stirring), followed by 30 min ultrasonic dispersion of NS/NA nanoparticles to create a stable suspension (Fig. 3). This suspension was then combined with dry ingredients (cement, sand, aggregate) and mixed for 1 min to achieve homogeneity. (2) Specimen fabrication involved casting: 100 mm3 cubic concrete samples for compressive strength testing, Φ50×60 mm3 mortar cylinders for MIP/SEM analysis, and 40×40×160 mm3 paste prisms for XRD/TGA characterization (Fig. 4). (3) Curing regime consisted of demolding after 12 hours, with subsequent curing under either standard conditions (20±2 °C) or low-temperature environment (5±0.2 °C in sealed bags, Fig. 5).

Fig. 3Ultrasonic disperser and resulting suspension. Photo taken by Dr. Yapeng Wang on February 22th, 2024 at the Experimental Laboratory Building of Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Fig. 4Photographic images of concrete, mortar, and cement paste specimens. Photo taken by Dr. Yapeng Wang on March 26th, 2024 at the Experimental Laboratory Building of Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Fig. 5Schematic and actual view of the low temperature curing chamber (5 ± 0.2 °C). Photo taken by Dr. Yapeng Wang on March 27th, 2024 at the Experimental Laboratory Building of Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences

2.4. Testing methods

2.4.1. Compressive strength measurement

The compressive strength of the concrete was measured at curing ages of 3, 7, 14, and 28 days in accordance with the Chinese standard GB/T 50081-2019 [41]. Testing was performed on triplicate 100 mm3 cubic specimens under displacement control at a constant loading rate of 0.5 MPa/s. The obtained strength values were subsequently multiplied by a size correction factor of 0.95.

2.4.2. Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP)

Following 28 days of curing, cylindrical mortar samples (Ф8×10 mm3) were extracted by coring and immediately immersed in ethanol to stop the hydration process. Before analysis, the specimens were dried in an oven at 60 °C to eliminate residual moisture without altering the microstructure, in accordance with reference [42].

2.4.3. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis

Hydration products were characterized using powdered cement paste samples (28-day curing) scanned from 5-90° 2 (0.02 °/s scan rate) with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer equipped with Cu-Kα radiation.

2.4.4. Scan electron microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure of the cement mortar was examined using SEM after 28 days of curing. Sample preparation involved drying at ambient temperature, followed by sputter coating with a thin gold layer at the paste-aggregate interface to enhance conductivity. The treated specimens were then scanned under SEM to observe morphological and microstructural features.

2.4.5. Statistical analysis

All macroscopic test results, including compressive strength and porosity, are reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) derived from three independent measurements. Statistical comparisons between group means were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc test applied for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at a p-value of less than 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Compressive strengths of concrete samples at different curing ages

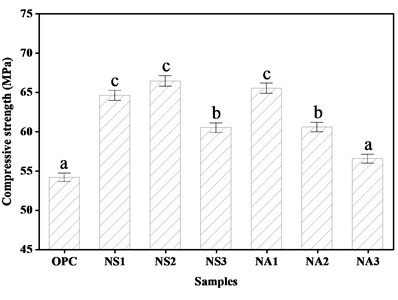

Fig. 6 presents the 28-day compressive strength of ordinary Portland cement concrete (OPC) and nano-modified concrete incorporating nano-silica (NS1-NS3) or nano-alumina (NA1-NA3). Notably, OPC exhibited the lowest compressive strength among all specimens. The strength evolution of nano-modified concretes displayed distinct trends: NS-modified concrete showed an initial strength enhancement followed by a decline with increasing NS content, while NA-modified concrete exhibited a monotonic strength reduction as NA dosage increased. Specifically, NS2 (2 % NS by cement weight) and NA1 (1 % NA by cement weight) achieved peak strength values, exceeding OPC by 23 % and 21 % respectively. This demonstrates that optimal nanomaterial incorporation ratios exist for strength enhancement – 2 % for NS and 1 % for NA by cement mass. Based on these findings, OPC, NS2, and NA1 were selected for subsequent comparative analysis of low temperature curing performance.

Specifically, the NS2 and NA1 mixes demonstrated optimal compressive strength, reaching 66.4 MPa and 65.5 MPa, respectively. Both values were significantly greater than those of the plain OPC group (54.2 MPa) ( 0.01). However, no statistically significant difference was observed between the NS2 and NA1 groups ( 0.05). In contrast, the compressive strength of the NS3 mixture was markedly lower than that of NS2 ( 0.05), suggesting that nanoparticle agglomeration at elevated dosages adversely affects mechanical performance.

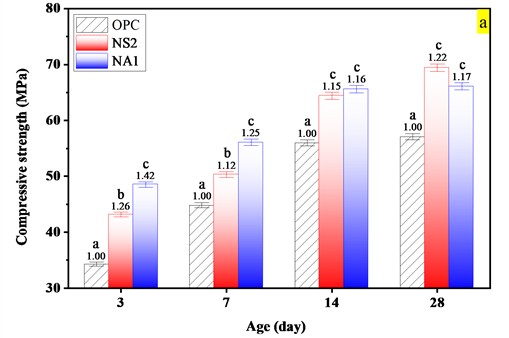

Fig. 628-day compressive strength of the samples (mean ± SD)

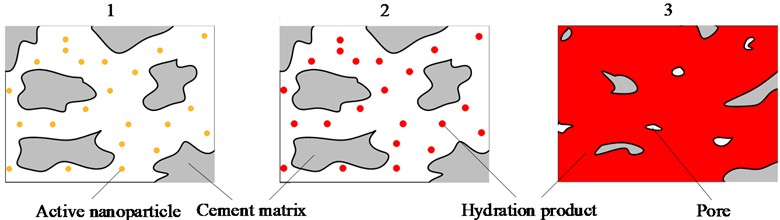

Fig. 7(a) demonstrates the compressive strength evolution of OPC, NS2 (2 % nano-silica), and NA1 (1 % nano-alumina) under 5°C curing, revealing three key trends: (1) All specimens exhibited age-dependent strength gain with declining growth rates; (2) NS2 and NA1 consistently surpassed OPC across curing ages (NA1: 1.42×, 1.25×, 1.16×, 1.17× vs OPC at 3/7/14/28 days; NS2: 1.26×, 1.12×, 1.15×, 1.22×), with NA1 dominating early strength (3-14 days) and NS2 excelling at 28 days; (3) The temporal divergence originated from nanomaterial-specific mechanisms – NA1’s sub-100 nm particles (160±20 m2/g surface area) accelerated early hydration via C₃A nucleation [43, 44], achieving 42 % strength boost at 3 days, while NS2’s sustained enhancement (22 % at 28 days) derived from dual pore-filling effects and prolonged pozzolanic reactions forming secondary C-S-H. Both nanomaterials enhanced crack resistance through interfacial bonding, yet excessive dosages triggered agglomeration due to high surface energy (NS: 160±20 m2/g), counteracting compactness gains.

Under low temperature curing conditions, both the NA1 and NS2 mixes exhibited significantly higher compressive strength than the OPC control at all testing ages ( 0.05 at 3 days; 0.01 at 7, 14, and 28 days). At the 3-day mark, NA1 showed a distinct early-age advantage over NS2, with a statistically significant strength difference ( 0.05). By 28 days, however, the difference between NA1 and NS2 was no longer statistically significant ( 0.05), suggesting that the pozzolanic reactivity of NS2 gradually matched the early performance of NA1 over time. Fig. 8 corroborates these mechanisms, showing NS/NA nanoparticles acting as nucleation cores to radially distribute hydrates, suppress CH/AFt crystal growth, and homogenize C-S-H distribution, ultimately yielding denser matrices through synergistic physical filling and chemical hydration modulation.

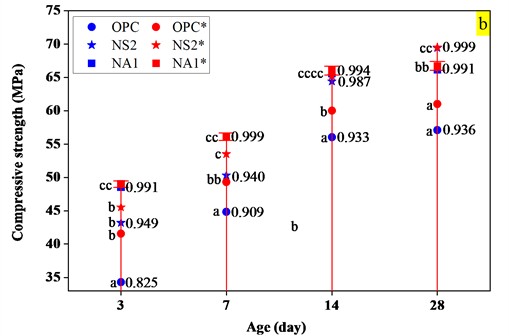

Fig. 7(b) contrasts the compressive strength of OPC, NS2, and NA1 under standard (20±2 °C) and low-temperature curing (5 °C), revealing three critical insights: (1) All specimens exhibited temperature-dependent strength reduction at 5 °C, with OPC showing the most pronounced decline (3 d: 0.825×; 28 d: 0.936× vs standard curing), whereas NA1 maintained near-equivalent performance (3 d: 0.991×; 28 d: 0.991×) and NS2 displayed progressive recovery (3 d: 0.949× → 28 d: 0.999×); (2) The minimal strength variance between curing regimes for NA1 (< 1 %) and NS2 (< 6 %) highlights their exceptional low-temperature adaptability compared to OPC (6.4-16.7 % loss); (3) NA1’s superior consistency across ages positions it as the optimal low-temperature concrete solution. This thermal resilience stems from nanomaterial-mediated hydration acceleration: NS/NA’s high surface energy (160-200 m2/g) counteracts low-temperature-induced hydration retardation [45] by enhancing nucleation efficiency (> 40 % dormant period reduction [14]) and sustaining secondary reactions (e.g., NS2's pozzolanic CH consumption). Notably, the prescribed dosages (2 % NS, 1 % NA) balance agglomeration risks and reactivity, achieving stable strength development while enabling year-round concrete placement – a breakthrough for cold-region construction engineering.

Fig. 7Development of compressive strength with curing age (*Curing temperature: 20 °C, mean ± SD)

Fig. 8Schematic illustration of the hydration mechanism of Portland cement incorporating active nanoparticles

3.2. Pore structure properties at 28 days

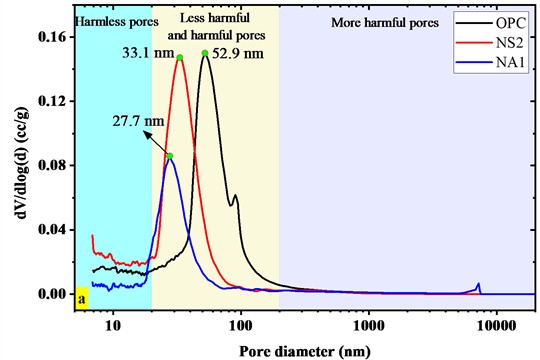

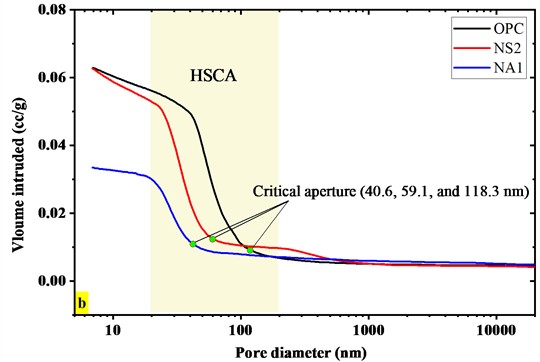

Fig. 9 delineates the pore structure evolution in OPC, NS2, and NA1 cement mortars through mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), revealing three critical nanomaterial effects: (1) Selective pore refinement: NS/NA preferentially modifies sub-200 nm pores, particularly reducing less-harmful (20-50 nm) and harmful (50-200 nm) pore volumes compared to OPC, as evidenced by differential curve shifts in Fig. 9(a); (2) Peak aperture optimization: The most probable pore diameters decrease sequentially from 52.9 nm (OPC) to 33.1 nm (NS2) and 27.7 nm (NA1), demonstrating NA1’s superior pore-narrowing capability despite lower dosage (1 % vs 2 % NS); (3) Critical threshold reduction: Cumulative intrusion curves (Fig. 9(b)) confirm drastic critical aperture reductions: 118.3 nm (OPC) → 59.1 nm (NS2) → 40.6 nm (NA1), indicating progressive conversion of macro-pores (> 200 nm) to meso/micro-pores through nanoparticle-driven pore-filling and hydration product redistribution. This microstructural densification correlates with NA1’s exceptional performance efficiency, where half the nanomaterial dosage (1 % vs 2 %) achieves 23 % greater critical aperture reduction than NS2. Mechanistically, the differential efficacy originates from NA's higher surface reactivity (Al2O3 vs SiO2) [4], enabling more effective nucleation site formation and calcium aluminate hydrate stabilization, thereby preferentially sealing transition zone pores (20-50 nm) that dominate permeability [46]. These findings establish quantitative guidelines for nanomaterial selection in pore structure engineering.

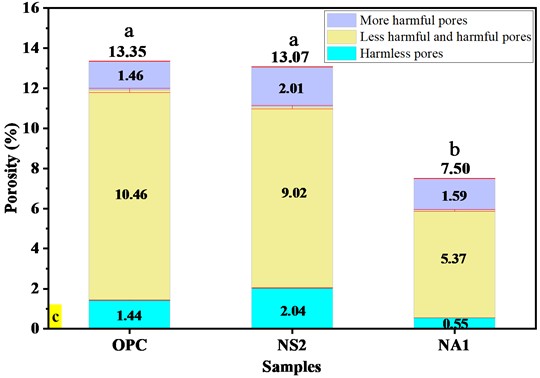

Fig. 9(c) quantifies the porosity evolution, revealing NA1’s exceptional microstructural refinement with 7.5 % total porosity versus 13.35 % (OPC) and 13.07 % (NS2). The porosity reduction in NA1 primarily targets critical pore categories – less-harmful and harmful pores, decreasing their combined volume from 10.46 % (OPC) to 5.37 %, compared to NS2’s marginal 1.42% reduction. The divergence stems from fundamental nanomaterial behaviors: (1) Hydration modulation: NA’s Al2O3 actively participates in early C₃A hydration [19], generating 25-30 % more hydration products to fill transition zone pores under low-temperature curing; (2) Dispersion efficacy: Despite NS’s higher specific surface area (200 vs 160 m2/g), its 2 % dosage exceeds the 1.5 % agglomeration threshold [30], creating localized voids (+0.8% porosity) that offset pore-filling benefits; (3) Crystal regulation: NA suppresses CH crystal growth (< 0.5 μm vs OPC's 2-3 μm) through epitaxial nucleation, whereas NS’s delayed pozzolanic reaction allows partial macropore (> 200 nm) retention. Crucially, NA1 counters the typical low-temperature pore coarsening effect [19], reducing dominant pore size range from 50-500 nm (baseline) to 20-100 nm through dual-phase refinement: 62 % decrease in > 200 nm pores and 40 % increase in < 50 nm pores. This paradigm shift demonstrates nano-alumina’s unique capability to reverse thermal degradation mechanisms in cementitious systems. As quantified in Fig. 8(c), the NA1 mixture exhibited a remarkably lower total porosity of 7.5 %, which was significantly different from both OPC (13.35 %) and NS2 (13.07 %) ( 0.001 for both comparisons). The difference in total porosity between the OPC and NS2 groups was not statistically significant ( 0.05), suggesting that while 2 % NS improved strength, it did not significantly alter the overall porosity compared to the control, likely due to agglomeration issues.

Fig. 9Pore structure characteristics of cement mortar (mean ± SD): a) pore size distribution; b) cumulative intrusion curve; c) total porosity

3.3. XRD analysis

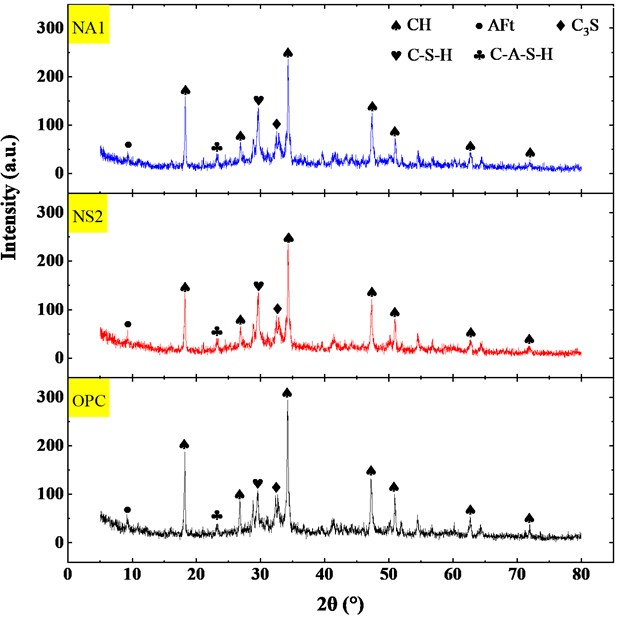

Fig. 10 displays the XRD patterns of OPC, NS2, and NA1 cement pastes cured at low temperature, offering key insights into the evolution of hydration products. All mixes showed identical phases – portlandite (CH), ettringite (AFt), calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), and calcium aluminate silicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) – along with residual C3S peaks of similar intensity, confirming that curing at 5 °C did not lead to anomalous crystalline formation. The CH diffraction peak intensities were similar in NS2 and NA1, suggesting comparable CH consumption with 2 % NS and 1 % NA incorporation under low-temperature conditions. Notably, NA exhibited a more efficient nano-effect at low temperature, achieving a similar performance to NS at half the dosage.

Weaker diffraction peaks were observed for AFt, C3S, C-S-H, and C-A-S-H across all samples, though discernible variations remained. The highest residual C3S content was found in OPC, followed by reduced levels in NS2 and NA1, indicating enhanced hydration in nano-modified mixes. While low temperature generally retarded hydration, both NS and NA mitigated this effect. No notable differences in AFt content were detected among the specimens. Importantly, the C-S-H and C-A-S-H diffraction signals were stronger in NS2 and NA1 than in OPC, implying greater formation of these gels – particularly with 2 % NS and 1 % NA producing comparable amounts. These gels contribute to pore refinement, increased density, and improved compressive strength, consistent with the mechanical performance results presented in Section 3.1.

Fig. 10XRD patterns of cement paste with and without NS/NA at 28 days

3.4. SEM analysis

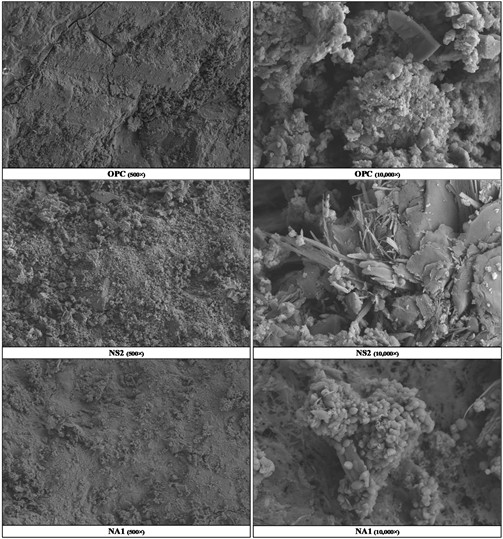

Fig. 11 presents SEM micrographs at 500× and 10,000× magnification, comparing the microstructural development of OPC, NS2, and NA1 samples cured at 5 °C. At lower magnification (500×), surface characteristics such as particle distribution, cracking, pores, and voids are observable. Both NS2 and NA1 exhibit superior surface integrity compared to OPC, showing relatively smooth surfaces with fewer cracks. The NA1 mix displayed the densest and most uniform morphology, whereas NS2, though generally flat, contained scattered loose particles. In contrast, the OPC surface appeared rough and disrupted by intersecting cracks, indicating poor microstructural coherence.

At higher magnification (10,000×), pore structure and microcracking became more distinct. The NA1 specimen showed the fewest pores and microcracks, followed by NS2, and then OPC with the most pronounced porosity. This refinement is attributed to the combined pozzolanic and filler effects of nano-additives, though some agglomeration of NS was observed at the higher dosage. Low temperature curing impeded hydration in plain OPC, leading to loosely bound particles and insufficient gel formation. The incorporation of NS or NA mitigated these effects, promoting a denser and more cohesive microstructure after 28 days. However, agglomeration at higher NS content resulted in localized inhomogeneity.

Overall, the SEM observations align with trends in compressive strength, MIP porosity, and XRD results, confirming that both nanomaterials – particularly NA at 1 % dosage – effectively enhance microstructural density, mechanical performance, and likely durability under low-temperature conditions.

Fig. 11SEM images of OPC, NS2, and NA1 samples at magnifications of 500× and 10,000×

4. Theoretical significance and practice

4.1. Theoretical significance

Our results provide novel insights into the synergistic mechanisms by which NS and NA co-influence the hydration process of cementitious systems. Specifically, we postulate that NS primarily acts as a nucleation site for C-S-H gel, accelerating early hydration, while NA preferentially reacts with calcium hydroxide and sulfate ions to promote the formation of stable AFm phases, thereby reducing porosity and enhancing later-age microstructural stability. The observed microstructural refinement, evidenced by MIP and SEM, challenges the existing model that these nanoparticles function merely as fillers and suggests a new role for hybrid NA-NS systems in simultaneously optimizing kinetics and long-term pore structure. Collectively, these findings contribute to a more fundamental and predictive understanding of how hybrid nano-additives can be used to tailor the properties of composite cement materials.

4.2. Industrial practice

The prospects for the industrial integration of this technology are multifaceted, encompassing scalability, economic and environmental benefits, specific applications, and necessary future steps. Translating this lab-scale research into industrial practice requires solving challenges related to the cost-effective, large-scale dispersion of nanoparticles and ensuring their safe handling. Although the initial cost may increase, the significant improvement in early-age strength offers economic advantages by enabling faster formwork removal and shortening construction schedules, while the enhanced durability extends service life and improves sustainability. This technology shows promise for high-value applications such as precast concrete elements, where high early strength boosts productivity; high-performance repair mortars that require rapid strength development and superior durability; and structures in aggressive environments, which benefit from a densified microstructure and reduced permeability. Successful implementation will depend on developing standardized guidelines, carrying out full-scale pilot projects in collaboration with industry partners, and conducting a comprehensive life-cycle assessment (LCA) to confirm the economic and environmental benefits.

5. Conclusions

In alignment with the objectives stated in the introduction, this study demonstrates that incorporating 2 % NS or 1 % NA effectively mitigates low-temperature (5 °C) curing-induced degradation in concrete. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

1) Conventional concrete suffers significant mechanical degradation when cured at 5 °C, exhibiting a 15-17 % loss in early strength (3 days) and a 6.4 % reduction in 28-day strength. This impaired performance stems from markedly retarded hydration – evidenced by a 40-50 % slower dissolution rate of C3S – accompanied by microstructural coarsening, which shifts the pore size distribution toward a more harmful dominant range of 20-200 nm.

2) NA1 achieves near-complete strength compensation (28 d: 0.991× vs. standard-cured OPC) via a dual-phase optimization mechanism. In contrast, NS2 exhibits progressive strength recovery (28 d: 0.999×), primarily driven by sustained pozzolanic consumption of CH and subsequent formation of secondary C-S-H. More notably, NA1-modified concrete fundamentally alters low-temperature failure modes, achieving a 44 % reduction in total porosity (from 13.35 % to 7.5 %) – far exceeding the 1.42 % reduction observed in NS2. This is accompanied by reduced surface crack density, due to enhanced C-A-S-H/CH interfacial reinforcement, and a shift in phase assemblage with lower CH and higher C-S-H content. Collectively, these microstructural modifications significantly enhance compressive strength and refine the pore structure of concrete under low temperature curing conditions.

3) The dosage-performance matrix (2 % NS vs. 1 % NA) establishes nano-alumina as the superior low-temperature modifier, delivering equivalent mechanical performance with a 50 % reduction in additive content. This breakthrough facilitates year-round concrete placement in cold regions (5 °C) without thermal curing, significantly reducing construction costs by eliminating heating and insulation requirements.

This study unveils a novel paradigm for low-temperature concrete technology: nano-alumina, at a mere 1 % dosage, outperforms the microstructural refinement achieved by 2 % nano-silica. This breakthrough in efficiency challenges conventional dosage strategies and positions NA as a transformative admixture for year-round concrete placement in cold climates, promising to attract broad interest from the international engineering community.

Although this study confirms the performance enhancement of nano-SiO2 and nano-Al2O3 under low-temperature curing, several practical aspects must be addressed to ensure successful industrial adoption. Future efforts should focus on optimizing large-scale dispersion techniques to prevent agglomeration and ensure mix uniformity, assessing the health and safety risks associated with handling nanomaterials—particularly airborne exposure during batching – and conducting full life-cycle assessments (LCA) to evaluate environmental impacts such as embodied energy and long-term durability. Collaboration with concrete producers and regulatory bodies will be essential to develop guidelines that facilitate safe, scalable, and sustainable implementation.

References

-

F. Sanchez and K. Sobolev, “Nanotechnology in concrete – A review,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 24, No. 11, pp. 2060–2071, Nov. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.03.014

-

L. P. Singh, S. R. Karade, S. K. Bhattacharyya, M. M. Yousuf, and S. Ahalawat, “Beneficial role of nanosilica in cement based materials – A review,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 47, pp. 1069–1077, Oct. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.05.052

-

A. H. Shekari and M. S. Razzaghi, “Influence of nano particles on durability and mechanical properties of high performance concrete,” Procedia Engineering, Vol. 14, pp. 3036–3041, Jan. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.07.382

-

M.-H. Zhang and H. Li, “Pore structure and chloride permeability of concrete containing nano-particles for pavement,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 608–616, Feb. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.07.032

-

Y. X. An, “Effect of nano materials on durability of high performance concrete,” Advanced Materials Research, Vol. 742, pp. 220–223, Aug. 2013, https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.742.220

-

S. Xu et al., “Environmental resistance of cement concrete modified with low dosage nano particles,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 164, pp. 535–553, Mar. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.188

-

S. D. Anitha Selvasofia et al., “Study on the mechanical properties of the nanoconcrete using nano-TiO2 and nanoclay,” Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 50, pp. 1319–1325, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.08.242

-

A. Zhang et al., “Durability effect of nano-SiO2/Al2O3 on cement mortar subjected to sulfate attack under different environments,” Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 64, p. 105642, Apr. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105642

-

“Guide to cold weather concreting,” American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills, MI, ACI 306R-16, 2016.

-

“Specification for winter construction of building engineering,” China Architecture and Building Press, Beijing, China, JGJ 104-2011, 2011.

-

R. Liu, H. Xiao, J. Liu, S. Guo, and Y. Pei, “Improving the microstructure of ITZ and reducing the permeability of concrete with various water/cement ratios using nano-silica,” Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 444–456, Aug. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-018-2872-5

-

M. Husem and S. Gozutok, “The effects of low temperature curing on the compressive strength of ordinary and high performance concrete,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 49–53, Feb. 2005, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2004.04.033

-

L. Soriano, J. Monzó, M. Bonilla, M. M. Tashima, J. Payá, and M. V. Borrachero, “Effect of pozzolans on the hydration process of Portland cement cured at low temperatures,” Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 42, pp. 41–48, Sep. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.05.007

-

Z. Zhang, Q. Wang, and J. Yang, “Hydration mechanisms of composite binders containing phosphorus slag at different temperatures,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 147, pp. 720–732, Aug. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.202

-

L.-H. Yang, Z. Han, and C.-F. Li, “Strengths and flexural strain of CRC specimens at low temperature,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 906–910, Feb. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.06.094

-

W. G. Sun, L. J. Liu, Q. H. Wu, and J. P. Feng, “Experimental research on hydration heat temperature of concrete box girder in low-temperature environment,” Applied Mechanics and Materials, Vol. 470, pp. 1045–1050, Dec. 2013, https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.470.1045

-

F. Karagöl, R. Demirboğa, M. A. Kaygusuz, M. M. Yadollahi, and R. Polat, “The influence of calcium nitrate as antifreeze admixture on the compressive strength of concrete exposed to low temperatures,” Cold Regions Science and Technology, Vol. 89, pp. 30–35, May 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2013.02.001

-

S. Kazemi Esfeh, H. Rong, W. Dong, and B. Zhang, “Experimental investigation on bond behaviours of deformed steel bars embedded in early age concrete under biaxial lateral pressures at low curing temperatures,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 303, p. 124419, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124419

-

L. Zhang et al., “Performance buildup of concrete cured under low-temperatures: use of a new nanocomposite accelerator and its application,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 335, p. 127529, Jun. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127529

-

B. Persson, “Long-term effect of silica fume on the principal properties of low-temperature-cured ceramics,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 27, No. 11, pp. 1667–1680, Nov. 1997, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-8846(97)00147-6

-

J. Liu, Y. Li, Y. Yang, and Y. Cui, “Effect of low temperature on hydration performance of the complex binder of silica fume-portland cement,” Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 75–81, Mar. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11595-014-0870-2

-

D. P. Bentz, P. E. Stutzman, and F. Zunino, “Low-temperature curing strength enhancement in cement-based materials containing limestone powder,” Materials and Structures, Vol. 50, No. 3, Apr. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-017-1042-6

-

E.-S. M. El-Kenawy et al., “Sunshine duration measurements and predictions in Saharan Algeria region: an improved ensemble learning approach,” Theoretical and Applied Climatology, Vol. 147, No. 3-4, pp. 1015–1031, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-021-03843-2

-

M. Mahmoud, “A review on waste management techniques for sustainable energy production,” Metaheuristic Optimization Review, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 47–58, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.54216/mor.030205

-

K. Khaled and M. K. Singla, “Predictive analysis of groundwater resources using random forest regression,” Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Metaheuristics, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 11–19, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.54216/jaim.090102

-

E.-S. M. El-Kenawy, N. Khodadadi, S. Mirjalili, A. A. Abdelhamid, M. M. Eid, and A. Ibrahim, “Greylag goose optimization: nature-inspired optimization algorithm,” Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 238, p. 122147, Mar. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122147

-

J. Stroh, M.-C. Schlegel, W. Schmidt, Y. N. Thi, B. Meng, and F. Emmerling, “Time-resolved in situ investigation of Portland cement hydration influenced by chemical admixtures,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 106, pp. 18–26, Mar. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.097

-

Q. Hu et al., “Direct three-dimensional observation of the microstructure and chemistry of C3S hydration,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 88, pp. 157–169, Oct. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2016.07.006

-

X. Lu, Z. Ye, L. Zhang, P. Hou, and X. Cheng, “The influence of ethanol-diisopropanolamine on the hydration and mechanical properties of Portland cement,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 135, pp. 484–489, Mar. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.191

-

C. Wang et al., “Research on the influencing mechanism of nano-silica on concrete performances based on multi-scale experiments and micro-scale numerical simulation,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 318, p. 125873, Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125873

-

Z. Liu, B. Lou, D. M. Barbieri, A. Sha, T. Ye, and Y. Li, “Effects of pre-curing treatment and chemical accelerators on Portland cement mortars at low temperature (5 ℃),” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 240, p. 117893, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117893

-

A. Joshaghani, M. Balapour, M. Mashhadian, and T. Ozbakkaloglu, “Effects of nano-TiO2, nano-Al2O3, and nano-Fe2O3 on rheology, mechanical and durability properties of self-consolidating concrete (SCC): An experimental study,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 245, p. 118444, Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118444

-

C. Li et al., “Influencing mechanism of nano-Al2O3 on concrete performance based on multi-scale experiments,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 384, p. 131402, Jun. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131402

-

C. Li et al., “Effects of nano-alumina on Portland concrete at low temperatures (5 ℃),” Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 20, p. e02922, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e02922

-

C. Li et al., “Modified cementitious materials incorporating Al2O3 and SiO2 nanoparticle reinforcements: An experimental investigation,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 19, p. e02542, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02542

-

C. Liu, C. Li, D. Chen, S. Fan, and Q. Zhang, “Effect of nano-silica on concrete properties under low-temperature environment,” (in Chinese), Journal Science Technology and Engineering, Vol. 25, pp. 3813–3820, 2025.

-

G. Liu et al., “Strength predictive models of cementitious matrix by hybrid intrusion of nano and micro silica: Hyper-tuning with ensemble approaches,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 26, pp. 1808–1832, Sep. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.07.222

-

S. Wang, L. Jian, Z. Shu, J. Wang, X. Hua, and L. Chen, “Preparation, properties and hydration process of low temperature nano-composite cement slurry,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 205, pp. 434–442, Apr. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.02.049

-

“Common Portland Cement,” China Standards Press, Beijing, China, GB 175-2007, 2007.

-

“Standard for technical requirements and test method of sand and crushed stone (or gravel) for ordinary concrete,” China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, China, JGJ 52-2006, 2006.

-

“Standard for test methods of concrete physical and mechanical properties,” China Architecture and Building Press, Beijing, China, GB/T 50081-2019, 2019.

-

“Pore size distribution and porosity of solid materials by mercury porosimetry and gas adsorption-part 1: Mercury porosimetry,” China Standards Press, Beijing, China, GB/T 21650.1-2008, 2008.

-

B. Han et al., “Nano-core effect in nano-engineered cementitious composites,” Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, Vol. 95, pp. 100–109, Apr. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.01.008

-

G. Land and D. Stephan, “Controlling cement hydration with nanoparticles,” Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 57, pp. 64–67, Mar. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2014.12.003

-

J. Liu, Y. Li, P. Ouyang, and Y. Yang, “Hydration of the silica fume-Portland cement binary system at lower temperature,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 93, pp. 919–925, Sep. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.05.069

-

Z. Zhang, J. Zhou, J. Yang, Y. Zou, and Z. Wang, “Understanding of the deterioration characteristic of concrete exposed to external sulfate attack: Insight into mesoscopic pore structures,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 260, p. 119932, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119932

About this article

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support for this study from the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Corporation of China (Grant No. 5200-202230098A-1-1-ZN).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Yapeng Wang: conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft preparation. Guoyu Li: conceptualization, funding acquisition. Chunqing Li: methodology, writing-review and editing. Jizhong Gan: validation. Dun Chen: formal analysis. Hang Zhang: investigation. Miao Wang: data curation. Xu Wang: data curation. Yan Zhang: validation. Liyun Tang: formal analysis.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.