Abstract

Strength degradation of steel structures due to corrosion is a significant durability concern globally, particularly in industrial environments where exposure to harsh conditions accelerates material deterioration. This study investigates the impact of long-term atmospheric corrosion on the mechanical properties and load-bearing capacity of circular hollow section (CHS) steel columns. The specimens dismantled from a substation structure exposed to an urban industrial environment for 30 years were subjected to tensile and axial compression experiments to analyze corrosion-induced deterioration. This research explores the correlation between corrosion rate and degradation of mechanical properties, such as yield strength, ultimate strength, and elasticity. A novel Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model is proposed to predict the remaining service life of corroded steel structures by integrating the effects of corrosion on these critical properties. Experimental results revealed a significant reduction in yield and ultimate strength due to uniform corrosion, with a direct linear relationship between the bearing capacity degradation and material loss. This study provides a crucial tool for engineers and infrastructure planners in managing the lifecycle of steel structures exposed to harsh environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

Steel circular hollow columns are extensively utilized in offshore platforms, wind turbine towers, and in electrical substation structures due to their high strength, favourable toughness, and superior strength-to-weight ratio. However, these structures are particularly vulnerable to corrosion, a frequent and inevitable consequence of prolonged exposure to the harsh and corrosive conditions inherent to industrial environments [1-4]. The urgency of this problem is magnified in the context of developing smart cities, where critical infrastructure is expected to be not only resilient but also intelligent and interconnected. The vision of 6G-enabled smart cities involves hyper-connected networks of sensors and systems for real-time governance, public safety, and resource management [5]. Furthermore, the proliferation of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), such as intelligent transportation networks, relies on a robust physical framework [6-7]. The structural integrity of core components like steel columns in substations and transmission towers is therefore foundational; their failure would disrupt not only power but also the digital ecosystems and data-driven services that define a modern smart city.

Under conditions of elevated air humidity and high concentrations of chloride (Cl−) and sulfate (SO2) ions, the corrosion rate of structural components accelerates significantly [8]. This accelerated corrosion of load-bearing members can lead to a reduction in their mechanical properties, posing a serious risk to the structural integrity and safety of structures [9]. Corrosion induces material loss, resulting in a reduction in the thickness of structural components, which in turn significantly compromises their mechanical properties and diminishes their load-bearing capacity [10-13].

The detrimental impact of corrosion on structural integrity is twofold. Firstly, uniform corrosion leads to a general thinning of the member wall, reducing the cross-sectional area and thus the overall load-bearing capacity. Secondly, and often more critically, localized pitting corrosion acts as a potent stress concentrator, initiating fatigue cracks that can drastically reduce the structure’s fatigue life under cyclic loading, such as that induced by wind vibrations or operational stresses [14-15]. While anti-corrosion coatings offer initial protection, they are not permanent. Long-term exposure and environmental factors can damage these coatings, allowing a water film to form on the steel surface and initiate electrochemical corrosion [16-19].

The primary structural components in substation frameworks are steel circular hollow sections (CHS) columns [20]. Corrosion significantly reduces their ultimate bearing capacity, thereby compromising the overall safety of the steel structures [21-24]. However, analysis of the mechanical properties of certain types of CHS columns under specific corrosion modes remains limited. A systematic evaluation of the bearing capacity deterioration and performance of corroded CHS columns holds substantial scientific and engineering value. The most widely employed research method for investigating the correlation between steel corrosion depth, corrosion rate, and exposure duration is the natural exposure corrosion test, wherein metal specimens are exposed to natural atmospheric conditions. This approach effectively captures the relationship between the corrosive environment, exposure duration, and the resulting degree of corrosion, providing valuable insights into real-world corrosion behaviour. Larrabee conducted one of the most comprehensive atmospheric corrosion rate studies, spanning 15.5 years and involving 270 types of engineering steels. The findings demonstrate that the corrosion resistance of high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels is significantly impacted by their chemical composition and the surrounding environmental conditions. This suggests that optimizing these factors can substantially enhance the durability of HSLA steels [25]. Honglun conducted a 30-year atmospheric exposure study on a steel structure, concluding that Q235 steel corrodes more rapidly in outdoor environments compared to other steels, primarily due to higher humidity and salt content. Conversely, sheltered conditions were found to reduce the corrosion rate, underscoring the critical role of environmental factors in determining the corrosion resistance of steel [26]. Wang tested carbon steel and low-alloy steel corrosion in urban air for one year. This concludes that low-alloy steels outperform carbon steels in resisting atmospheric corrosion due to certain alloying elements. It emphasises the need to select suitable steel compositions for specific environmental conditions to enhance durability and reduce corrosion-related degradation [27]. Da-Ning tested the influence of a corrosive environment on carbon steel corrosion over nine years. The study concludes that long-term atmospheric corrosion significantly affects the metals in structures, with steel being the most susceptible [28]. Although the natural exposure corrosion test has a high accuracy, it is time-consuming, and it is not possible to analyse the mechanical properties of a particular configuration in a short period.

Many studies focused on accelerated corrosion and simulated corrosion. Cinitha performed axial compression tests on corroded round steel pipe specimens using the accelerated corrosion method and found that yield and ultimate strengths were drastically reduced [29]. Wang employed machining to manufacture penetrating circular hole flaws on round steel pipes to study the effects of evenly distributed and randomly distributed pitting defects on their axial compressive bearing capacity [30]. Qu performed local corrosion and axial compression tests on fixed-length round steel pipes by outdoor periodic spraying and found that corrosion duration affected ultimate bearing capacity more than stiffness [31]. Nazari used a finite element model-based semi-empirical formula to predict the relationship between round steel pipe corrosion and axial compressive bearing capacity and discussed the variation of bearing capacity degradation when the corrosion depth ratio, diameter/thickness ratio, slenderness ratio, and hoop size are changed by one variation [32]. Ahn studied the residual bearing capacity of inclined steel pipes with local corrosion that was mechanically processed and considered the full and semi-ring corrosion conditions [33]. The rectangular corrosion area was tilted 45° to demonstrate the effect of the corrosion angle in different environments. Rajabipour examined the size determinants of the plastic zone near corrosion holes in a finite element analysis of round steel pipes with pitting and axial compression [34]. Zhang confirmed that a corroded round steel pipe has drastically reduced load-carrying capacity [35]. While these studies can provide better insights into the impact of corrosion on the structure’s mechanical properties, their lack of natural exposure to corrosion prevents them from illustrating the progression of corrosion from mild to severe stages [36-39].

Predicting the remaining life of steel transmission towers involves various methodologies that assess structural integrity, environmental factors, and material degradation. Peng proposes a fuzzy reliability evaluation method that establishes a reduction model for foundation resistance over time. This model allows for the determination of remaining service life based on reliability thresholds validated through specific engineering cases. Usman presents a method that combines condition assessments and corrosion hazard data to predict the remaining life of lattice steel towers. Their approach employs a scoring method and survival function analysis, demonstrating its applicability in maintenance planning. Ma introduces a regression neural network model for online monitoring of insulator deterioration, which indirectly influences the transmission tower’s remaining life. This model enhances risk assessment through real-time data analysis.

Research into corrosion effects has often relied on accelerated testing or simulated corrosion (e.g., machined pits) to study capacity degradation. While these methods provide valuable insights, they frequently lack the fidelity to replicate the progressive, complex morphology of natural corrosion, particularly the stochastic nature of pitting. Furthermore, a significant portion of the existing literature and assessment models focus on the residual strength under static loading conditions. Many existing models for predicting the remaining life of corroded structures, such as those applied to pipelines, are predominantly based on probabilistic methods or stress analysis under idealized conditions. These approaches often possess key limitations: They are frequently calibrated for uniform corrosion and may neglect the severe, localized stress concentration effects of pitting corrosion, which is a dominant failure initiator in many atmospheric exposures. Models are often validated under constant-amplitude loading, raising questions about their accuracy and conservatism under the complex, dynamic loading spectra (e.g., from wind vibration, seismic events, or operational transients) that structures encounter in service. There is a notable scarcity of methodologies specifically developed and validated for key structural elements like welded joints in CHS columns, which are hotspots for both corrosion and fatigue damage.

The primary innovation of this study lies in the development of a Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model that moves beyond conventional geometric-based assessments. While existing models, such as the one proposed by Adasooriya and Siriwardane [1] for bridges, often rely on probabilistic data or stress concentration factors derived from idealized pit geometries, they frequently overlook the direct and measurable degradation of the material’s intrinsic mechanical properties (yield strength, ultimate strength) due to long-term corrosion. This paper introduces a novel damage factor, the Material Degradation Coefficient (), which is empirically derived from tensile tests on naturally corroded specimens. Our model directly integrates this coefficient to predict the time-dependent decay of load-bearing capacity, offering a more physically grounded and material-specific approach to remaining life estimation for structural steel components.

This study aims to bridge these identified gaps by developing a more robust methodology for assessing corroded steel CHS columns, with a specific focus on axial load-bearing capacity and its implications for remaining service life. The objectives of this paper are threefold: To experimentally and numerically investigate the degradation of mechanical properties in CHS columns subjected to natural exposure corrosion, explicitly considering the material loss and stress concentration effects associated with the resulting corrosion morphology. To develop and validate high-fidelity Finite Element (FE) models, calibrated against experimental data from axial loading tests, that can accurately simulate the behaviour of corroded members under axial compression. To propose and demonstrate a novel, integrated methodology for estimating the remaining service life of corroded steel structures. This method moves beyond conventional approaches by systematically incorporating the measured reduction in mechanical properties due to actual corrosion damage, providing a more physically grounded and reliable prediction tool for engineers. By focusing on the axial performance of CHS columns under realistic corrosion damage and linking this directly to a service life estimation framework, this work provides a targeted contribution to the assessment and maintenance of critical steel infrastructure.

2. Experimental program

2.1. Preparation of specimens

In this study, eight circular hollow columns were selected, including one intact specimen and seven specimens exhibiting varying degrees of corrosion. These columns were extracted from the Zhenyang substation. This structure had been subjected to atmospheric corrosion for 30 years, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The substation columns were fabricated from Q235 mild steel, a material commonly used in construction, with its chemical composition detailed in Table 1. The steel tube columns studied in this paper, which had undergone 30 years of corrosion, were all in normal service at a substation. The corrosion these columns experienced was primarily uniform atmospheric corrosion. Although some localized corrosion was also present, it was generally concentrated at the ends of the components. During sampling and test preparation, these end sections were typically cut off and removed. Each specimen had a nominal length of 410 mm, an external diameter of 100 mm, and a designed thickness of 3 mm; however, the measured thickness varied depending on the extent of corrosion.

Fig. 1Zhenyang 220kV substation’s corroded steel columns

Table 1Chemical composition of Q235 steel

Elements | C | Mn | Si | S | P | O | N |

Conc. (%) | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.025 | 0.02 | 0.015 | 0.0015 |

Over the decades, environmental factors contributed to the progressive corrosion of the steel pipes. The corrosion primarily affected the external surfaces of the pipes, while the internal surfaces remained largely intact. The outer surface of the steel pipes exhibited uniform corrosion, leading to the formation of a reddish-brown rust layer. This layer, a direct consequence of industrial weathering, is indicative of prolonged exposure to aggressive environmental conditions typical of industrial regions.

2.2. Environmental conditions of the substation

The substation is situated in Yancheng, Jiangsu province, China, an area that has experienced substantial environmental and climatic changes over the past 30 years, driven by rapid industrialization, urbanization, and changing climate patterns. The substation is likely to experience specific challenges due to these environmental factors, particularly concerning corrosion. The city has faced challenges with air pollution, including particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and ozone (O3). Studies have shown that pollutant levels generally peak during winter months; the environmental characteristics of Yancheng are given in Table 2. Air pollution, primarily from industrial emissions and vehicle exhaust, combined with the city’s climatic conditions, leads to occasional severe acid rain.

Table 2Weather conditions at the Zhenyang substation location over the last 30 years

Avg. temp. in summer (°C) | Avg. temp. in winter (°C) | Avg. humidity in winter (%) | Avg. humidity in summer (%) | Avg. rainfall (mm) | Avg. wind speed (m/s) |

30 °C-31 °C | 3 °C-7 °C | 62 %-66 % | 80 %-86 % | 38 | 2.8 m/s-3.7 m/s |

2.3. Corrosion rate

The rust layer on the corroded specimens was dark brownish-yellow, with the outer layer being loose and easily peeled off. The zinc anti-corrosive paint on the intact specimens and the rust from the corroded specimens were removed following international standards, using a solution composed of 50 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl), 3.5 g of hexamethylenetetramine, and distilled water at room temperature. After cleaning, the specimens were dried before measuring the thickness loss with a standard ultrasonic thickness gauge.

This study used a new Single-Point Differential Measurement (SPDM) method to measure the average corrosion depth of corroded specimens. The average corrosion depth is calculated by directly comparing the initial thickness with the corroded thickness at the key points and averaging the results. Compared with traditional thickness measurement methods, the core idea of the SPDM is to perform a differential operation between two measurements of the same point under different times or conditions, or between a single measurement and a fixed reference value. This approach effectively eliminates systematic errors and environmental interference (such as temperature drift and zero-point offset), thereby accurately extracting changes or absolute values of the target physical quantity. It achieves a good balance between usability and accuracy, making it well-suited for rapid and reliable assessment. The average corrosion depth for each specimen was determined from ten-point measurements taken across the corroded surface area. Each specimen’s average corrosion depth (Dc) is calculated as follows:

For each point, the local corrosion depth is determined by subtracting the post-exposure thickness from the initial thickness: , where represents each measurement point. The SPDM technique provides a simple yet effective way to measure the average corrosion depth of a specimen. By focusing on a few strategically chosen points and using straight forward thickness measurements, this method offers a balance between ease of use and accuracy, making it an excellent choice for quick assessments or situations where simplicity is key.

2.4. Tensile specimens

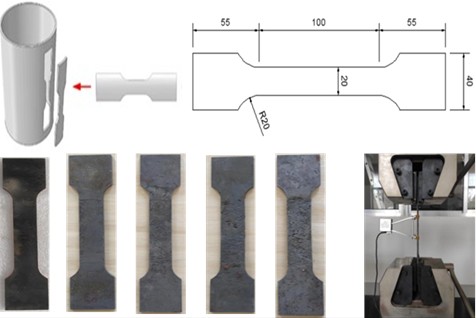

For tensile experiments, a total of 16 specimens were prepared from the corroded steel columns, the rust was cleared by a physical method. Tensile specimens, including fourteen corroded and two uncorroded, were cut into standard samples for tensile testing following GB/T228.1-2021. The corroded tensile specimens were directly extracted from the corroded column sections of the field-retrieved columns, thus their material degradation reflects authentic service conditions. The dimensions of the conventional tensile coupon, 210 mm long, 20 mm wide, and thickness varied as per corrosion depth, made of Q235 steel shown in Fig. 2. The unidirectional tensile test of the steel specimens was conducted using a 100 kN capacity electronic universal testing machine (CMT5105).

The engineering stress is calculated using the minimum cross-sectional area, which was measured at the fracture location after testing using a digital Vernier calliper, and the corresponding minimum cross-sectional area was established. A gauge line was drawn 25 mm from the centre point on both sides of the front and back sides of the specimen, and its purpose was to obtain the elongation after the break of the specimen by measuring the distance of the gauge section again after the tensile test.

Fig. 2Tensile experiment specimens and testing setup

A full-scale extensometer with an adjustable gauge length was employed to collect strain within the given range of the gauge length of 50 mm. Using the strain rate control test method, the tensile test is carried out according to GB/T 228. In this test, the loading rate of the steel before yield is 1mm/min, and the loading rate after yield is 5 mm/min. The engineering stress-strain values are directly obtained from experiments and then converted to true stress-strain by using:

where and is the engineering stress and strain and and is the true stress and strain, respectively. Their assessment is essential for a more thorough evaluation of material behaviour. Table 3 lists the calculations of the experimental results, where is ultimate strength, is yield strength, is Modulus of elasticity, is ultimate strain, is yield strain and is fracture strain.

2.5. Axial loading setup

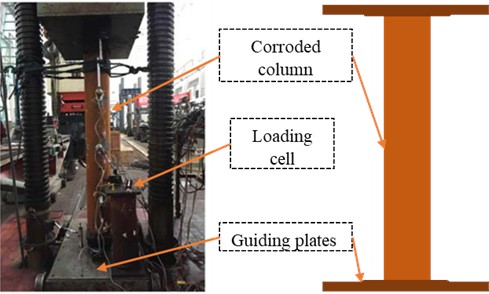

The axial loading test was conducted using a 200-ton electro-hydraulic servo-pressure testing machine in the structural laboratory of Southeast University. Fig. 3 illustrates the dynamic acquisition instrument used, with strain data being collected simultaneously throughout the loading process. The strain acquisition was performed using the strain tester TST3826-2, as depicted in Fig. 3. Given the symmetrical cross-section of the round steel pipe, the strain gauges were arranged based on the principle of uniform symmetry. Specifically, the strain gauges were positioned in the upper, middle, and lower sections of the specimen, with the upper and lower sections centred 2 cm from each end. To monitor the structural behaviour and detect failure modes, the specimens were equipped with eight linear variable differential transducers (LVDTs). Two LVDTs were oriented orthogonally to measure both longitudinal and transverse strains, while four additional LVDTs were used to gauge axial compressive deformations. This setup ensured comprehensive monitoring of the specimen’s responses under axial loading.

The restraint configuration of the testing machine features a hinged connection at the lower end of the loading device, with the vertical loading end fixed at the upper end. The entire loading process was conducted using a hierarchical loading system. The experimental loading mode employed force-controlled loading with an initial loading rate of 1 kN/s. During this phase, the load-displacement curve was closely monitored. As the curve approached the end of the linear elastic region and neared the elastic limit, the loading rate was reduced to 0.5 kN/s to allow for more precise control. Loading continued until the specimen exhibited plastic deformation and eventual failure, with strain data being collected throughout the process. The field setup for loading is depicted in Fig. 3. As shown in the figure, the lower end is connected to the loading plate, which in turn is attached to a movable cart. The cart was designed to facilitate specimen installation and alignment. During the experiment, however, the cart remained stationary, allowing the lower end of the column to be reasonably regarded as fixed.

Fig. 3Experimental setup for axial loading test

The steel columns were taken with different corrosion rates, and the localized corrosion ratio calculated as:

where is the corrosion-damaged column thickness, as measured by an ultrasonic thickness gauge, and is the designed thickness of the column. The load-carrying capacities of the experimental and simulated corroded columns were and , respectively.

The deterioration ratio of the ultimate strength of the tested specimens is calculated as:

where and are the ultimate load capacity of the intact and corroded columns, respectively. For the strain and stress data as well as the related plots, please refer to Section 4.1 of this paper.

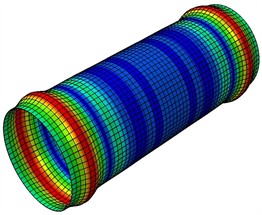

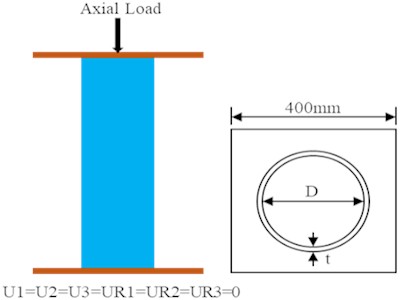

3. Numerical simulation

Abaqus software utilized to develop a finite element model (FEM) of the circular hollow steel columns. The model incorporated encastre boundary conditions, where the lower end of the column was fully fixed, and the upper end was restrained in all directions except along the longitudinal axis. A displacement-controlled loading approach was employed, dividing the compression process into smaller incremental steps to capture the detailed structural response, as shown in Fig. 4. The accuracy of the simulation is highly dependent on the mesh arrangement. For this study, the element type C3D8R (an 8-node linear brick, reduced integration, hourglass control) was selected for modelling the column specimens, providing a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The optimum mesh size 10 mm is selected for column’s, as shown in Fig. 4, ensuring that the mesh density was sufficient to capture the local variations in geometry and stress concentrations due to corrosion.

Material properties assigned to the model’s reflected those obtained from the tensile experimental tests. The model geometry and dimensions were consistent with those of the physical column specimens. After constructing the FEM, simulations were conducted to validate the numerical model against experimental data. Nonlinear analysis was performed, which included material nonlinearity, large deformations, and contact interactions, to verify the results obtained from the corroded column specimens, ensuring the reliability and robustness of the simulation approach.

Fig. 4Numerical model

a) Mesh density

b) Boundary conditions

The Finite Element Method (FEM) was selected as the primary comparison and validation tool for this study due to its well-established capability in accurately simulating the nonlinear behavior of metallic structures, including material plasticity, large deformations, and complex boundary conditions. While analytical models for corroded members exist, they often rely on significant simplifications regarding corrosion morphology and its effect on stress distribution. The FEM, particularly with the C3D8R element chosen for its efficiency in handling contact and plasticity, allows for a direct, physics-based replication of the actual corroded geometry and the experimentally measured stress-strain response. This makes it a superior benchmark for validating our experimental results and for conducting virtual parametric studies that would be prohibitively expensive or time-consuming to perform physically.

4. Mechanical properties degradation

4.1. Stress-strain curves

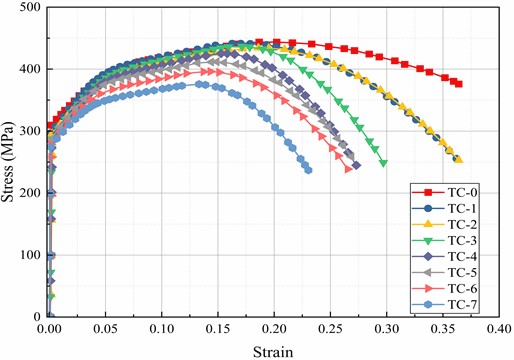

The stress-strain curves of the specimens with varying degrees of corrosion are shown in Fig. 5. As the corrosion rate increases, significant changes are observed in the stress-strain behaviour. As detailed in Table 3, the ultimate tensile strength, yield strength, and elastic modulus of the steel specimens decrease notably with increasing corrosion, primarily due to the thickness loss caused by corrosion. Furthermore, the elongation at break decreases sharply as the corrosion rate rises, with the values falling below the specification requirements. The strengthening phase of the stress-strain curve becomes markedly shorter in corroded specimens compared to non-corroded ones, indicating a reduced capacity for plastic deformation. Both ultimate strain and yield strain decrease significantly as a result of corrosion. For instance, the TC-7 specimen exhibited a 15.08 % reduction in ultimate strength and a 10.45 % reduction in yield strength compared to the intact specimen. Additionally, the ultimate strain and fracture strain decreased by 30.24 % and 36.21 %, respectively.

This degradation in mechanical properties is attributed to the combined effects of reduced thickness and stress concentrations induced by corrosion-related defects. These defects include uneven thickness reduction, enlarged rust pits, and surface roughness, which exacerbate the material's vulnerability to failure. As a result, the stress-strain curves of corroded specimens display shorter strengthening phases and more pronounced brittle fracture characteristics, leading to an earlier onset of plastic damage and reduced overall ductility.

Table 3Mechanical properties of Q235 mild steel specimens

Specimen ID | (%) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (GPa) | ||

TC-0 | 0 | 443.71 | 312.1 | 208.155 | 0.1776 | 0.3612 |

TC-1 | 2.7 | 442.54 | 300.1 | 202.163 | 0.1543 | 0.3584 |

TC-2 | 3.5 | 434.38 | 298.3 | 197.482 | 0.1460 | 0.3110 |

TC-3 | 5.2 | 436.08 | 290.13 | 196.424 | 0.1594 | 0.2981 |

TC-4 | 7.1 | 425.19 | 287.46 | 198.765 | 0.1441 | 0.2675 |

TC-5 | 8.6 | 412.38 | 291.4 | 194.534 | 0.1370 | 0.2712 |

TC-6 | 9.5 | 397.41 | 283.2 | 195.462 | 0.1305 | 0.2651 |

TC-7 | 12.1 | 376.80 | 279.5 | 192 .664 | 0.1239 | 0.2304 |

Fig. 5Engineering stress-strain curves of tensile specimens

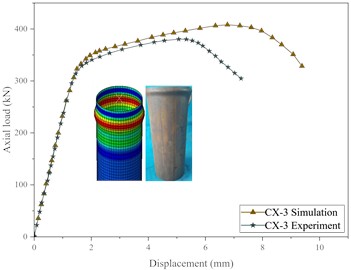

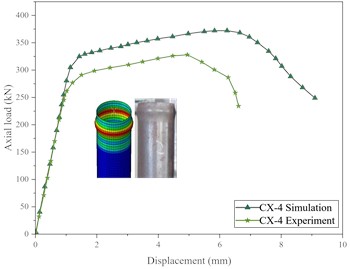

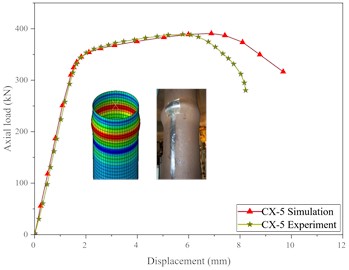

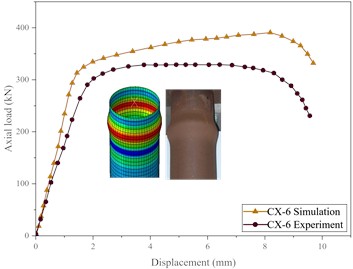

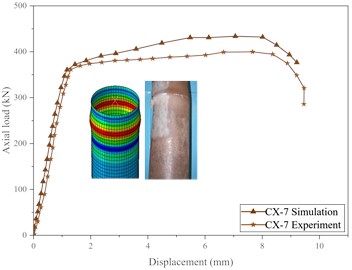

4.2. Load-displacement curves

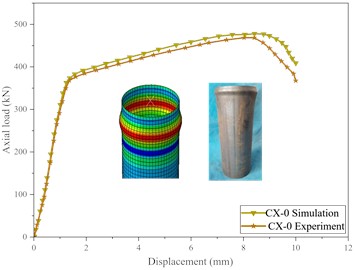

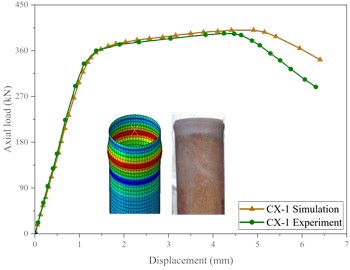

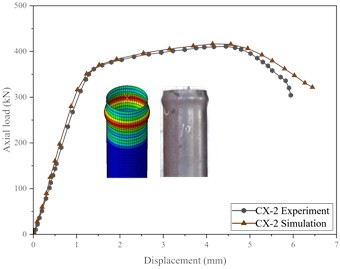

Experiments were conducted on corroded steel columns to evaluate their performance under axial compression. The results revealed that, during the initial loading phase, the load-displacement curves of the specimens exhibited a predominantly linear behaviour, with minimal surface deformation. However, as the load increased, the columns transitioned into plastic deformation, leading to significant distortions at both ends. Upon reaching the ultimate load, buckling was consistently observed at the ends of all specimens. The axial load-displacement curves, presented in Fig. 6, clearly demonstrate the influence of corrosion on the deformation behaviour under axial loading. Corrosion not only reduced the ultimate load capacity but also led to shallower slopes in the initial stages of deformation, indicating a decrease in rigidity and structural integrity. The presence of corrosion accelerated the onset of plastic deformation and reduced the columns load-bearing capacity. While the load-deformation curves for specimens with similar corrosion levels exhibited consistent slopes, variations in ultimate load capacity were evident due to differences in localized corrosion patterns.

Corrosion significantly compromised the structural integrity of the circular hollow columns, leading to increased axial deformation under compression. As the degree of corrosion intensified, the resulting strain increased, further diminishing the material’s stiffness and ultimate load capacity. The maximum load-bearing capacity of each specimen was quantified, and the rate of degradation due to corrosion was systematically calculated, highlighting the detrimental impact of corrosion on the structural performance of steel columns.

4.3. Effect of / ratio caused by corrosion

The reduction in thickness due to corrosion increases the ratio, thereby accelerating the decline in compressive strength. The experimental results demonstrated a significant decrease in compressive strength with an increasing diameter-to-thickness () ratio, a critical parameter affecting the load-bearing capacity of corroded steel columns. Corrosion intensifies these effects by further compromising the structural integrity of the steel columns. As the ratio increased, the restraint effect weakened, leading to a deterioration in material properties and a subsequent reduction in ultimate compressive strength. Specifically, specimens with lower ratios exhibited outward deformation upon failure, with no noticeable local buckling. In contrast, specimens with higher ratios showed pronounced local buckling near the points of maximum load, reflecting a more brittle failure mode.

This is evident in the CX-4 specimen, given in Table 4, which had the highest ratio of 36.36 and the lowest ultimate strength of 327.99 kN, representing a 29.99 % reduction compared to less corroded specimens. The stress-strain curves for these specimens, as depicted in the results, illustrate a steep decline in load-bearing capacity as corrosion progresses, with the curves becoming shorter and steeper as the material’s ductility and strength diminish. The presence of corrosion not only reduces the ultimate strength but also increases the susceptibility to local buckling and other failure mechanisms, particularly in specimens with higher ratios.

Table 4Column specimen dimensions and Experimental and FEM results

Specimen ID | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | (kN) | (kN) | / | (%) | (%) | |

CX-0 | 100 | 410 | 3 | 3 | 33.33 | 468.52 | 477.84 | 1.02 | – | – |

CX-1 | 100 | 412 | 3 | 2.86 | 34.96 | 393.89 | 400.48 | 1.02 | 4.67 | 15.93 |

CX-2 | 100 | 409 | 3 | 2.91 | 34.36 | 411.1 | 416.59 | 1.01 | 3.00 | 12.26 |

CX-3 | 100 | 413 | 3 | 2.83 | 35.34 | 380.32 | 408.11 | 1.07 | 5.67 | 18.83 |

CX-4 | 100 | 414 | 3 | 2.75 | 36.36 | 327.99 | 372.11 | 1.13 | 8.33 | 29.99 |

CX-5 | 100 | 407 | 3 | 2.84 | 35.21 | 389.17 | 390.76 | 1.00 | 5.33 | 16.94 |

CX-6 | 100 | 409 | 3 | 2.82 | 35.46 | 329.06 | 390.63 | 1.19 | 6.00 | 29.77 |

CX-7 | 100 | 411 | 3 | 2.90 | 34.48 | 399.80 | 433.76 | 1.08 | 3.33 | 14.67 |

Mean error | 1.065 | |||||||||

Standard deviation | 0.0670 | |||||||||

95 % confidence interval | 1.009,1.121 | |||||||||

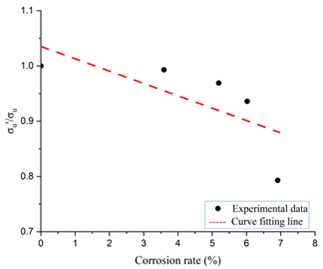

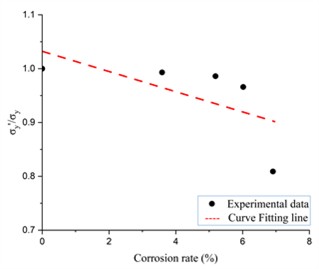

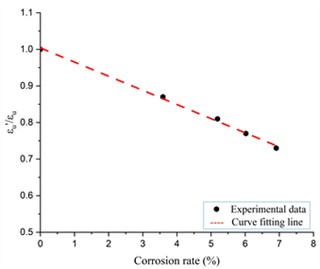

4.4. Ultimate strength reduction

Fig. 6 presents the results of this study, showing a clear reduction in key mechanical parameters, yield strength, ultimate strength, elongation, elastic modulus, and ultimate strain of Q235 steel as the corrosion rate increases. This decline is consistent with findings from previous literature, which attribute the deterioration primarily to a stress concentration around corrosion pits. The stress concentration exacerbates the local deformation, leading to a reduction in the overall mechanical performance of the steel.

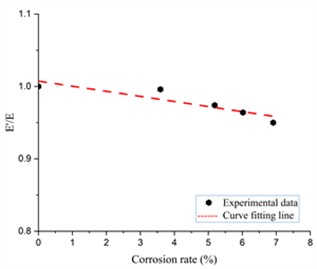

The malleability of Q235 steel, which is crucial for its structural applications, is particularly compromised by these stress concentration effects. The relationship between the mechanical properties of Q235 steel and the corrosion rate is depicted in Fig. 7. This figure illustrates a linear decrease in the yield strength, ultimate strength, elongation, elastic modulus, and ultimate strain of corroded Q235 steel, underscoring the detrimental impact of corrosion on structural stability. As corrosion progresses, the ability of the steel to withstand loads diminishes, leading to a higher likelihood of failure under stress, especially in structural applications where these mechanical properties are critical.

Fig. 6Axial load vs vertical displacement curves of corroded circular steel column specimens

a) CX-0

b) CX-1

c) CX-2

d) CX-3

e) CX-4

f) CX-5

g) CX-6

h) CX-7

The results clearly demonstrate that as the corrosion rate increases, key mechanical properties including yield strength, ultimate strength, elongation, elastic modulus, and fracture strain exhibit a marked decline. This degradation is primarily attributed to stress concentration around corrosion pits, which exacerbates the reduction in ductility and overall structural performance of the steel. The yield strength, ultimate strength, elongation, elastic modulus, and fracture strain of corroded Q235 steel decrease linearly with increasing corrosion rates, indicating a systematic and predictable deterioration in mechanical properties. Corrosion-induced defects, such as pitting and surface roughness, intensify the stress concentration effects, further weakening the material's capacity to withstand applied loads.

The study also compares the load-vertical displacement curves obtained from finite element analysis (FEA) with those from experimental tests. The comparison reveals that the FEA results closely match the experimental data in both trend and shape, particularly in the initial stiffness of the curves for short columns. For uniformly corroded components, as the corrosion rate increases, the initial stiffness of the load-vertical displacement curve decreases, reflecting the diminished structural integrity. The average corrosion rate and the coefficient of variation of pitting depth emerge as critical factors influencing the load-bearing capacity of uniformly corroded components, underscoring the significant impact of corrosion on the mechanical properties and ultimate strength of steel columns.

Fig. 7Degradation ratio corrosion rate

a) Ultimate strength ratio

b) Yield strength ratio

c) Ultimate strain ratio

d) Modulus of elasticity ratio

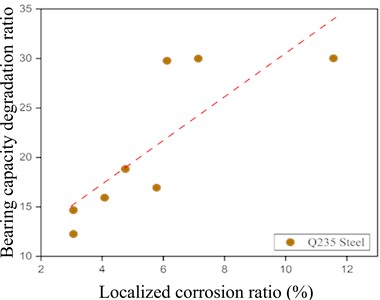

A significant reduction in column thickness due to corrosion was the primary cause of failure in all test specimens. Corrosion not only reduced the cross-sectional area but also altered the failure modes of the columns. The weakening effect of corrosion on the column ends led to local bulging deformation at the edges during testing. At maximum stress, the specimens exhibited noticeable bending, with their axes forming a half-sinusoidal shape. As the applied force progressively decreased, the deflection of the specimens increased correspondingly. The experimental results indicate that the overall discrepancy between the test data and the finite element simulation results was maintained within 5 % for most of the specimens, demonstrating the reliability of the simulation model. These findings underscore the critical impact of corrosion on structural stability and highlight the importance of accounting for corrosion-induced degradation in both experimental and numerical analyses. Fig. 8 illustrates a clear linear relationship between the degradation rate of bearing capacity and the weight loss rate of round steel under conditions of uniform corrosion.

Fig. 8Bearing capacity degradation ratio with localized corrosion ratio

5. Proposed method for remaining life estimation

5.1. Corrosion-mechanical interaction model

The Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model is an advanced approach for predicting the remaining life of steel structures by integrating the effects of corrosion on the material’s mechanical properties. This model accounts for how corrosion degrades critical mechanical properties such as yield strength, tensile strength, and toughness over time, reducing the structure’s ultimate load-carrying capacity. By understanding this interaction, the remaining life of corroded steel structures can be calculated more accurately. The primary goal of the Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model is to predict the degradation of a steel structure’s load-bearing capacity over time due to corrosion. This model considers the material properties degrade as corrosion progresses and how this degradation affects the structure’s ability to withstand applied loads.

Unlike other models that only consider cross-sectional area loss, our approach accounts for the deterioration of the steel’s inherent strength. The coefficient α is not a theoretical constant but an empirical parameter calibrated from experimental data. It quantifies the rate at which the yield strength decays per unit of corrosion rate over time.

The corrosion rates of the steel tube columns examined in this study exhibited notable variations. Some columns corroded more rapidly, while others degraded at a slower pace. These differences are likely attributed to their distinct locations and varying service environments. Observations indicate that corrosion occurred predominantly in a uniform manner, with localized non-uniform corrosion appearing only at a limited number of positions. The material degradation function models how the mechanical properties of steel deteriorate over time due to corrosion. The function is expressed as:

where is yield strength at time , is yield strength of intact specimen, CR is corrosion rate (mm/year) and is material degradation coefficient, which is derived from empirical data or experimental results. The function represents an exponential decay of the mechanical property over time, indicating that as corrosion progresses with a higher CR, the mechanical properties degrade more rapidly. The model explicitly incorporates time (), allowing for the prediction of mechanical property degradation at any point during the structure’s service life. The value of is crucial and determined from experimental data specific to the type of steel and environmental conditions. The degradation of mechanical properties affects the ultimate load capacity of the steel structure over time. This is modelled as:

where is ultimate load capacity at time , is initial ultimate load capacity before corrosion and is calculated as, , is yield strength, is cross-section area.

5.2. Remaining life calculation

The remaining life of the steel structure is estimated by determining when the ultimate load capacity falls below a critical threshold . This threshold represents the minimum load capacity required for safe operation. The remaining life is calculated using the equation:

The remaining life of the substation structure is calculated based on the mechanical properties of specimens that are obtained from tensile experiments. These mechanical properties have been mentioned in (Table 3). Based on experimental data and the corrosion rate of carbon steel Q235, the Corrosion degradation factor is taken as 0.05 per year, which is a critical parameter in the Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model, representing the rate at which corrosion impacts the mechanical properties of steel over time. The remaining service life of the substation steel columns, determined using the yield strength of the TC-0 specimen, is estimated to be 33 years. To further validate this model, the remaining life was also calculated based on the yield strength of the TC-7 specimen, resulting in an estimate of 30 years. The accuracy of the proposed model exceeds 95 %. As TC-7 is the most severely corroded specimen and TC-0 represents the new (uncorroded) condition, the remaining service life in this study is derived based on the complete life cycle from the pristine state (TC-0) to the loss of load-bearing capacity. According to this formulation, the more severe the corrosion, the shorter the remaining life and the greater the associated estimation error. Consequently, TC-7 exhibits the largest error. This model provides a detailed and accurate prediction of the remaining life by considering both the corrosion rate and the degradation of mechanical properties. It can be applied to various types of steel structures and adjusted for different mechanical properties and environmental conditions.

Eq. (8) is fundamental in modelling the time-dependent degradation of materials under corrosive environments, and it is verified by the plotted curves for different values of on the graph. A higher results in a steeper decline in yield strength, meaning the material will lose its mechanical properties more quickly under the same corrosive conditions. Conversely, a lower slows down the degradation process, preserving the material’s strength for a longer period. The proposed model offers a more focused and scientifically substantiated approach to understanding and predicting the life expectancy of steel structures under corrosive influences. This model’s strength lies in its ability to integrate real-world corrosion rates with the resultant mechanical degradation, providing a crucial tool for engineers and maintenance planners to manage the lifecycle of critical infrastructure.

To quantitatively validate the proposed model, its predictions were compared against a conventional method that estimates remaining life based solely on cross-sectional area loss. This area-loss method assumes that load capacity degrades linearly with thickness reduction. The model by Adasooriya and Siriwardane [1] is a notable example for fatigue life assessment of corroded bridges. While our focus is on axial capacity, a parallel can be drawn: their model incorporates a corrosion fatigue strength reduction factor based on pit depth, whereas our model uses the empirically-derived coefficient to account for the broader material degradation. For the TC-7 specimen (highest corrosion), the conventional area-loss method predicts a load capacity reduction of 12.1 % (equal to the thickness loss). However, our experiments measured an actual ultimate strength reduction of 15.08 %. Our proposed model, using the coefficient, accurately captured this higher level of degradation (as shown in the accurate life prediction based on TC-7 data). The conventional method, by ignoring the reduction in material strength, would overestimate the remaining load capacity by approximately 3 %. In terms of remaining life, this translates to an overestimation of several years, which could have critical implications for structural safety. This comparison underscores the conservatism and improved accuracy of the proposed Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model, as it captures degradation mechanisms that pure geometric models miss.

6. Conclusions

This study has presented a comprehensive investigation into the deleterious effects of long-term atmospheric corrosion on the mechanical performance and residual capacity of Q235 steel circular hollow section (CHS) columns. The experimental and analytical findings lead to the following principal conclusions:

1) A direct correlation was established between increasing corrosion rates and the progressive deterioration of key mechanical properties. The most severely corroded specimen (TC-7) exhibited substantial reductions, including a 15.08 % loss in ultimate strength, a 10.45 % loss in yield strength, ultimate strain and fracture strain decreased by 30.24 % and 36.21 %, respectively.

2) The primary mechanism of degradation is the corrosion-induced thinning of the steel wall, which directly diminishes the cross-sectional area and leads to a pronounced reduction in axial load-bearing capacity. This elevates the vulnerability of structural members to premature failure under service loads.

3) A novel Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model was developed for assessing the remaining life of corroded steel CHS columns and validated, which quantitatively links corrosion rate to the degradation of mechanical properties. This model represents a significant advancement over conventional methods by explicitly integrating material property loss into the remaining life assessment, thereby enabling more accurate and scientifically-grounded predictions.

4) Applied to the case study of substation structures, the model estimates a remaining service life ranging from 30 to 33 years, contingent upon the specific mechanical property (yield strength) used as the failure criterion. This narrow window highlights the criticality of timely intervention.

5) A key future direction is the integration of the proposed Corrosion-Mechanical Interaction Model into a smart structural health monitoring (SHM) framework. By combining periodic thickness measurements from drones or fixed sensors with the predictive model presented here, a cyber-physical system could be developed. This system would provide real-time updates on remaining life, predict maintenance needs, and automatically alert managers, transforming passive infrastructure into an intelligent, self-reporting asset. This would represent a significant step forward in realizing the full potential of safe, durable, and data-driven smart cities.

This research unequivocally demonstrates that uniform atmospheric corrosion critically undermines the axial compression performance of structural steel members. The proposed model provides a practical tool for engineers to enhance the reliability of structural integrity assessments and optimize maintenance strategies for critical infrastructure. Future work should focus on extending the model's applicability to a broader range of steel grades, cross-sectional shapes, and heterogeneous corrosion patterns to further solidify its role in predictive infrastructure asset management.

References

-

N. D. Adasooriya and S. C. Siriwardane, “Remaining fatigue life estimation of corroded bridge members,” Fatigue and Fracture of Engineering Materials and Structures, Vol. 37, No. 6, pp. 603–622, Jan. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1111/ffe.12144

-

Z.-D. Xu, Y.-P. Shen, and Y.-Q. Guo, “Semi-active control of structures incorporated with magnetorheological dampers using neural networks,” Smart Materials and Structures, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 80–87, Feb. 2003, https://doi.org/10.1088/0964-1726/12/1/309

-

Y. Xu et al., “Investigation of the dynamic properties of viscoelastic dampers with three-chain micromolecular configurations and tube constraint effects,” Journal of Aerospace Engineering, Vol. 38, No. 2, Mar. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1061/jaeeez.aseng-5141

-

X.-Y. Liu, Z.-D. Xu, X.-H. Huang, Y. Tao, X. Du, and Q. Miao, “Seismic response analysis of three-dimensional base isolation structures considering rocking and P-Δ effects,” Engineering Structures, Vol. 328, p. 119689, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2025.119689

-

S. Rafique, S. Iqbal, D. Ali, and F. Khan, “Navigating ethical challenges in 6G-enabled smart cities: privacy, equity, and governance,” ICCK Transactions on Sensing, Communication, and Control, Vol. 2, No. 1, p. 48, Mar. 2025, https://doi.org/10.62762/tscc.2025.291581

-

S. H. Ali, I. Ullah, S. A. Ali, M. I. U. Haq, and N. Ullah, “A cyber-physical system based on on-board diagnosis (OBD-II) for smart city,” IECE Transactions on Intelligent Systematics, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 49–57, Sep. 2024, https://doi.org/10.62762/tis.2024.329126

-

X. Jin, “Editorial: intelligent systematics: a new transactions,” ICCK Transactions on Intelligent Systematics, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1–2, Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.62762/tis.2024.100001

-

B. Dong et al., “Corrosion failure analysis of low alloy steel and carbon steel rebar in tropical marine atmospheric environment: Outdoor exposure and indoor test,” Engineering Failure Analysis, Vol. 129, p. 105720, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2021.105720

-

Y. Yuan, N. Zhang, H. Liu, Z. Zhao, X. Fan, and H. Zhang, “Influence of random pit corrosion on axial stiffness of thin-walled circular tubes,” Structures, Vol. 28, pp. 2596–2604, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2020.10.080

-

R. Wang and R. A. Shenoi, “Experimental and numerical study on ultimate strength of steel tubular members with pitting corrosion damage,” Marine Structures, Vol. 64, pp. 124–137, Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marstruc.2018.11.006

-

Z.-D. Xu and Y.-P. Shen, “Intelligent bi-state control for the structure with magnetorheological dampers,” Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 35–42, Jan. 2003, https://doi.org/10.1177/1045389x03014001004

-

Z.-W. Hu et al., “Full-scale shaking table test on a precast sandwich wall panel structure with a high-damping viscoelastic isolation and mitigation device,” Engineering Structures, Vol. 329, p. 119797, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2025.119797

-

Y. Tao, Z. D. Xu, Y. Wei, X. Y. Liu, Y. R. Dong, and J. Dai, “Integrating deep learning into an energy framework for rapid regional damage assessment and fragility analysis under mainshock-aftershock sequences,” Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics, Vol. 52, No. 6, 2025.

-

R. Wang, H. Guo, and R. A. Shenoi, “Experimental and numerical study of localized pitting effect on compressive behavior of tubular members,” Marine Structures, Vol. 72, p. 102784, Jul. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marstruc.2020.102784

-

Y. Zhao, X. Zhou, F. Xu, and T.-M. Chan, “Numerical simulation of corroded circular hollow section steel columns: A corrosion evolution approach,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 197, p. 111594, Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.111594

-

Z. Lu, Z. Wang, Y. Zhou, and X. Lu, “Nonlinear dissipative devices in structural vibration control: A review,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 423, pp. 18–49, Jun. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2018.02.052

-

R. Yao, Y. Xu, R. Zhang, Y. Zhang, and J. Zhou, “Unbalance compensation based on speed fault-tolerance and fusion strategy for magnetically suspended PMSM,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 224, p. 111991, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.111991

-

Y. Zhou, Y. Xu, J. Zhou, Y. Zhang, and J. Mahfoud, “Numerical and experimental investigations on the dynamic behavior of a rotor-AMBs system considering shrink-fit assembly,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 224, p. 111980, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.111980

-

Z.-D. Xu, P.-P. Gai, H.-Y. Zhao, X.-H. Huang, and L.-Y. Lu, “Experimental and theoretical study on a building structure controlled by multi-dimensional earthquake isolation and mitigation devices,” Nonlinear Dynamics, Vol. 89, No. 1, pp. 723–740, Mar. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-017-3482-5

-

W. Zhang, S. Chen, Y. Zhu, S. Liu, W. Chen, and Y. Chen, “Experimental study on the axial compression behavior of circular steel tube short columns under coastal environmental corrosion,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 200, p. 111929, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.111929

-

H. Wang, Z. Zhang, H. Qian, and F. Fan, “Effect of local corrosion on the axial compression behavior of circular steel tubes,” Engineering Structures, Vol. 224, p. 111205, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111205

-

Z.-D. Xu, Q. Tu, and Y.-F. Guo, “Experimental study on vertical performance of multidimensional earthquake isolation and mitigation devices for long-span reticulated structures,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 18, No. 13, pp. 1971–1985, Dec. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546311429338

-

Y. Yang, Z.-D. Xu, Y.-W. Xu, and Y.-Q. Guo, “Analysis on influence of the magnetorheological fluid microstructure on the mechanical properties of magnetorheological dampers,” Smart Materials and Structures, Vol. 29, No. 11, p. 115025, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665x/abadd2

-

Z.-D. Xu, C. Zhu, and L.-W. Shao, “Damage identification of pipeline based on ultrasonic guided wave and wavelet denoising,” Journal of Pipeline Systems Engineering and Practice, Vol. 12, No. 4, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)ps.1949-1204.0000600

-

C. P. Larrabee, “Corrosion resistance of high-strength low-alloy steels as influenced by composition and environment,” Corrosion, Vol. 9, No. 8, pp. 259–271, Aug. 1953, https://doi.org/10.5006/0010-9312-9.8.259

-

W. Honglun, Y. Hua, and C. Hui, “Corrosion behavior of Q235 steel by outdoor exposure and under shelter in atmosphere of Hainan coastal,” (in Chinese), Journal of Chinese Society for Corrosion and Protection, Vol. 42, pp. 223–234, 2022.

-

Q. Wang, Z. Li, F. Wang, and H. Li, “Fatigue life prediction of power transmission towers based on nonlinear finite element analysis,” Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 106–114, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.2478/amns.2023.2.00630

-

Y. Da-Ning, W. Chuan, Z. Y. Wang, F. Chuan-Fu, and P. Chen, “Atmospheric corrosion of common metals used in transformer substation and protection measures,” Zhuangbei Huanjing Gongcheng, Vol. 14, pp. 100–105, 2016.

-

A. Cinitha, P. K. Umesha, and N. R. Iyer, “An overview of corrosion and experimental studies on corroded mild steel compression members,” KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, Vol. 18, No. 6, pp. 1735–1744, Sep. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-014-0362-0

-

H. Wang et al., “Effect of pitting defects on the buckling strength of thick-wall cylinder under axial compression,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 224, pp. 226–241, Nov. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.07.074

-

H. Qu, W. Zhang, C. Kou, R. Feng, and J. Pan, “Experimental investigation of corroded CHS tubes in the artificial marine environment subjected to impact loading,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 169, p. 108485, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2021.108485

-

M. Nazaria, M. R. Khedmati, and A. F. Khalaj, “A numerical investigation into ultimate strength and buckling behavior of locally corroded steel tubular members,” Latin American Journal of Solids and Structures, Vol. 11, No. 6, pp. 1063–1076, Nov. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-78252014000600010

-

J.-H. Ahn, W. R. Choi, S. H. Jeon, S.-H. Kim, and I.-T. Kim, “Residual compressive strength of inclined steel tubular members with local corrosion,” Applied Ocean Research, Vol. 59, pp. 498–509, Sep. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2016.07.002

-

A. Rajabipour and R. E. Melchers, “A numerical study of damage caused by combined pitting corrosion and axial stress in steel pipes,” Corrosion Science, Vol. 76, pp. 292–301, Nov. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2013.07.002

-

Z. Zhang, S. Xu, B. Nie, R. Li, and Z. Xing, “Experimental and numerical investigation of corroded steel columns subjected to in-plane compression and bending,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 151, p. 106735, Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2020.106735

-

H. Chen, H. Liu, Z. Chen, and Y. Xiong, “Experimental investigation of ultimate bearing capacity of corroded welded hollow spherical joints,” Structures, Vol. 57, p. 105127, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105127

-

Z.-D. Xu, F.-H. Xu, and X. Chen, “Intelligent vibration isolation and mitigation of a platform by using MR and VE devices,” Journal of Aerospace Engineering, Vol. 29, No. 4, Jul. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)as.1943-5525.0000604

-

Z. Lu, S. Zhao, C. Ma, and K. Dai, “Experimental and analytical study on the performance of wind turbine tower attached with particle tuned mass damper,” Engineering Structures, Vol. 294, p. 116784, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.116784

-

Y. Zhao, J. Zhou, M. Guo, and Y. Xu, “A thermal flexible rotor dynamic modelling for rapid prediction of thermo-elastic coupling vibration characteristics in non-uniform temperature fields,” Applied Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 138, p. 115751, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2024.115751

About this article

This research was funded by Jiangsu Fangtian Electric Power Technology Co., Ltd. Technology Project (0FW-23542-JS).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Yu Wan: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing-original draft preparation, investigation, project administration. Junpeng Ma: funding acquisition, writing-review and editing, resources. Chi Wang: formal analysis, software, data curation.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.