Abstract

Q235 low-carbon steel is widely used in construction, bridges, machinery manufacturing and other fields because of its good plasticity and weldability. To explore the optimized application of laser welding technology in Q235 steel processing, this study used an EEF-LWM-1500 welding machine and systematically investigated the effect of different welding speeds on the joint quality of Q235 steel under the condition of a constant laser power of 1200 W. The weld quality was systematically evaluated through multiple characterization methods, including metallographic microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, tensile testing, microhardness measurement, electrochemical corrosion tests, and friction-wear experiments. Experimental results indicated that a welding speed of 120 mm/min caused burn-through in the steel plate, while increasing the speed to 240 mm/min achieved good joint formability. Notably, the heat-affected zone gradually decreased with higher welding speeds. The hardness and tensile strength of the laser-welded zone both exceeded those of the base material. Specifically, the average hardness of the weld zone peaked at 177.56 HV when the welding speed was 500 mm/min. Below this speed, hardness increased with rising welding speed, while it tended to decrease above 500 mm/min. Tensile strength showed a similar trend, with the highest value of 424.98 MPa and the lowest value of 421.94 MPa. Electrochemical corrosion tests revealed that the welded joint at 500 mm/min exhibited the smallest self-corrosion current density (1.41×10⁻5 A/cm2) and the largest capacitive arc radius, confirming optimal corrosion resistance. This study identifies that the optimal laser welding speed for Q235 steel is 500 mm/min, which provides important technical references for improving the welding quality and production efficiency of Q235 steel in practical production and expanding its application scope.

Highlights

- Welding speed had no significant effect on the microstructure type of each joint zone, yet grain size increased with increasing speed.

- The weld contained lath martensite and had the highest hardness across the joint, peaking at 177.56 HV at a welding speed of 500 mm/min.

- All welded joints featured a lower average friction coefficient than the base metal.

1. Introduction

Laser welding is a precision joining technology that uses a high-energy laser beam as the heat source [1]. By focusing the beam to generate local high temperature, it melts materials and forms welds. It offers multiple advantages, such as high energy density, small heat-affected zone, fast welding speed, and high automation [2-3]. This technology is widely applied in industries like automotive, electronics, aerospace, and medical devices. Q235 is a carbon structural steel widely used in construction, bridges, and mechanical manufacturing [4-6]. This material has a carbon content of 0.12 %-0.20 % and a yield strength not lower than 235 MPa. It exhibits good plasticity and weldability, but there is still a risk of cold cracking during welding [7-9]. The welding process must be comprehensively formulated based on factors such as plate thickness, joint type, and service environment, with emphasis on controlling heat input and cooling rate [10-12].

In the applied research of laser welding technology, scholars have conducted systematic explorations on process optimization and mechanism analysis for different material systems. Yu Chenqian et al. [13] studied laser wire-arc welding of Q235 steel and found that introducing beam scanning technology reduced the molten pool temperature gradient by approximately 30 %, effectively inhibiting the growth of coarse columnar crystals, refining ferrite grains to 1/2 of the original structure, increasing weld elongation by 25 %, and improving gap bridging ability to 0.3 mm by expanding the laser action area. To address welding defects in high-strength steel, Li Jingyi [14] confirmed that laser-CMT hybrid welding can compensate for the shortcomings of TIG welding. Compared with the 40 % defect rate of pure TIG welding, the hybrid welding reduces the spatter rate from 15 % to 3 % through the concentrated energy of the laser beam and CMT arc wire filling compensation. This technology has been successfully applied to welding titanium alloy components in aerospace, with joint strength reaching 95 % of the base metal. For laser lap welding of Q235 steel and 6061 aluminum alloy, Jia Ziyan [15] determined the optimal parameters through orthogonal tests. When the laser power is 850 W and the speed is 30 mm/s, the weld forms a 50 μm transition layer, the tensile strength reaches 210 MPa (close to 80 % of the aluminum alloy base metal), and the heat-affected zone shows a gradient distribution of “lath martensite-fine grain zone-coarse grain zone”. Rasoul Safdarian et al. [16] found in the study of Q235 tailor-welded blanks that when the average joint thickness increases from 2 mm to 4 mm, the weld hardness increases from HV220 to HV260 due to the decrease in cooling rate, and the hardness of the heat-affected zone decreases in a gradient. Weifeng Xie et al. [17] found in Q345 steel that increasing the welding speed can promote the formation of acicular ferrite, increasing the impact energy by 60 %. For quenched and tempered steel, S Afkhami et al. [18] confirmed that laser welding does not significantly soften S1100 steel, and rapid cooling inhibits carbide precipitation. In the field of titanium alloys, Krishna K. Vamsi et al. [19] found that increasing the welding speed reduces heat input by 40 %, forming fine equiaxed crystals in the fusion zone, and increasing joint strength by 15 % to 980 MPa, revealing the dominant role of fine grain strengthening. Yasho Narayan et al. [20] successfully fabricated dissimilar joints between P92 ferritic/martensitic steel and Inconel 625 superalloy with a plate thickness of 10 mm using laser beam welding process. Their research revealed that the weld metal exhibits a columnar-cellular austenitic microstructure, and the joints suffer from chemical composition inhomogeneity at both macro- and micro-scales, which originates from the mixing and diffusion behaviors of the two base metals during welding. Additionally, the carbides and intermetallic compound phases formed in the weld metal exert a significant influence on the mechanical properties of the joints. Yasho Narayan et al. [21] conducted a study on dissimilar laser beam welded joints of 316L stainless steel and Inconel 625 superalloy. The results indicated that the weld metal presents an asymmetric solidification characteristic, which directly reflects the non-equilibrium segregation phenomenon during rapid solidification. Impact performance tests showed that the energy absorption value of the weld metal is significantly lower than that of the two base metals, revealing that the weld zone is the weak link in the mechanical properties of the joints. Moulali et al. [22] welded heat-resistant P92 steel plates by laser beam welding. Systematic analysis of as-welded and post-weld heat treated (PWHT) joints demonstrated that the joints achieved complete penetration with negligible internal defects. Further research confirmed that the post-weld heat treatment process can significantly improve the impact toughness of the joints by regulating the microstructure of the joints [23]. These studies, from single-material optimization to composite technology innovation and dissimilar metal joining, form a logical chain from mechanism analysis to engineering application, providing multi-dimensional references for laser welding research of low-carbon steel.

Building on the widespread application of Q235 steel and the notable advantages of laser welding technology, this study transcends the constraints of traditional single-performance-focused research by innovatively employing laser tailor-welding technology. With the laser power fixed at 1200 W and other process parameters held constant, welded joints were fabricated through the adjustment of laser welding speed. Moving beyond one-dimensional performance analysis, this research systematically explores the synergistic influence mechanism of varying welding speeds on the quality, macro- and microstructural morphology, mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and frictional properties of Q235 steel welded joints. Its core objective is to accurately identify optimal welding process parameters, which in turn enhances the welding quality and production efficiency of Q235 steel, expands its application scenarios, and further provides novel support – integrating theoretical depth and practical value – for the large-scale adoption of laser welding technology in low-carbon steel processing.

Leveraging both the extensive use of Q235 steel and the inherent advantages of laser welding, this study introduces an innovative approach via the adoption of laser tailor-welding technology. Welded joints were produced by modifying the laser welding speed, while maintaining a constant laser power of 1200 W and keeping other process parameters unchanged. Unlike conventional studies that focus solely on single-performance metrics, this research conducts a comprehensive investigation into the effects of different welding speeds on the quality, macro- and microstructural morphology, mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and frictional properties of Q235 steel welded joints. It aims to explore optimal welding processes, with the goals of improving the welding quality and production efficiency of Q235 steel, broadening its application scope, and laying a robust foundation for the widespread implementation of laser welding technology.

2. Materials and method

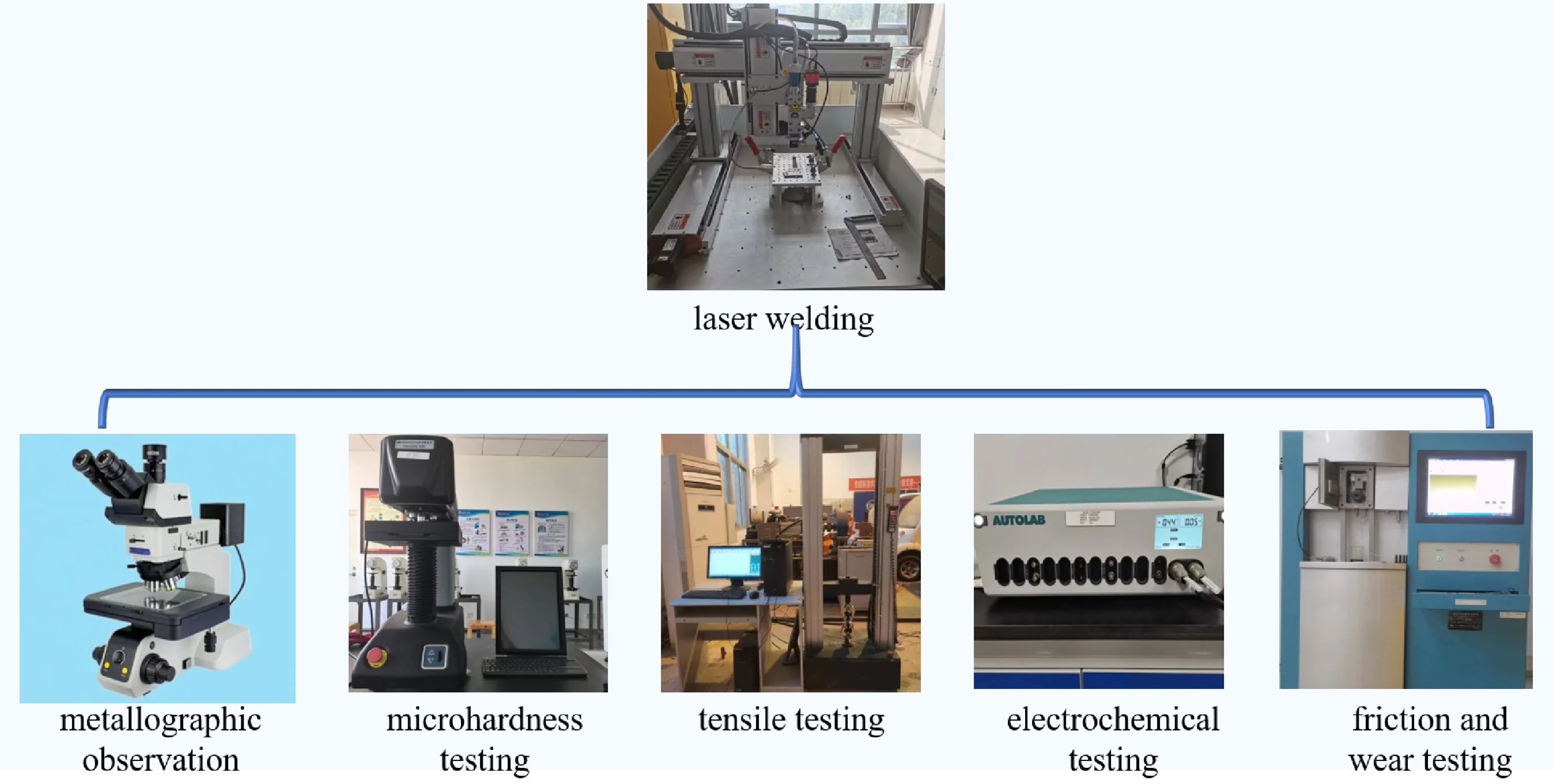

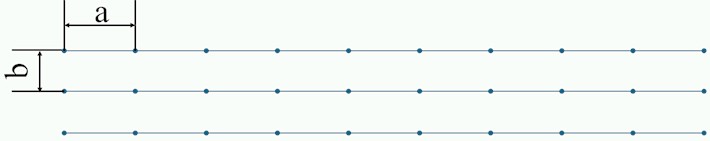

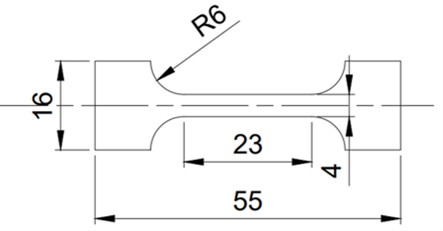

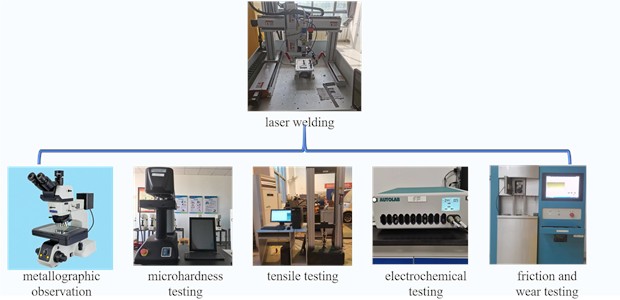

In this experiment, Q235 low-carbon steel plates with a thickness of 2 mm were selected, and their basic composition is shown in Table 1. Prior to welding, the Q235 steel plates need to be polished with 1000-grit sandpaper to remove the surface oxide layer. The laser welding machine of model EFE-LWM-1500 was used to weld the Q235 thin plates in a butt joint manner. During the welding process, the laser power was maintained at 1200 W, and the welding was carried out at speeds of 120, 240, 300, 400, 500, and 600 mm/min. Microhardness testing: vickers hardness was measured with three parallel dot arrays (30 points in total) arranged in the weld zone, as shown in Fig. 1(a). The horizontal spacing of the arrays was adjusted according to the width of the welded joint: for welding speeds of 240-300 mm/min, the spacing parameters were set to 0.8 mm and 0.3 mm; for 400–500 mm/min, 0.7 mm and 0.3 mm; and for 600 mm/min, 0.6 mm and 0.3 mm. After point-by-point measurement, the vertices of the diamond-shaped indentations were manually calibrated to reduce errors, and the average value of each column of points was used for analysis. Tensile testing: welded workpieces were wire-cut into standard tensile specimens (with dimensions adapted to a 4 mm×2 mm cross-section, as shown in Fig. 1(b). The specimens were loaded at a rate of 1 mm/min, and the maximum force, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation after fracture were recorded. After fracture, the specimens were hermetically stored for subsequent fracture analysis, and all specimens fractured in the base metal region. Electrochemical corrosion testing: using a 3.5 % NaCl solution as the corrosive medium, impedance testing was first performed under open-circuit potential, followed by polarization testing (to avoid interference of polarization with impedance results, the corrosive solution was replaced for each test). The self-corrosion current density and self-corrosion potential were calculated via the extrapolation method on polarization curves, and corrosion resistance was analyzed by combining the capacitive arc radius from impedance spectra. Friction and wear testing: a high-speed block-on-ring wear tester was adopted. Welded workpieces were cut into standard specimens of 19.10 mm×12.15 mm×12.40 mm and fixed on a pad. The test parameters were set as follows: load of 100 N, temperature of 24 °C, rotation speed of 150 r/min, and duration of 1800 s. Before and after the test, the specimen mass was weighed using a balance with a precision of 0.001 g to calculate the wear loss, and the friction coefficient variation curve was recorded. The experimental and testing process is shown in Fig. 1(c).

Table 1Chemical Composition of Q235 Steel

Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Mo | Ti | Al |

Content (wt.%) | ≤ 0.22 | ≤ 0.35 | ≤ 1.40 | ≤ 0.045 | ≤ 0.05 | ≤ 0.30 | ≤ 0.30 | ≤ 0.08 | ≤ 0.025 | ≤ 0.015 |

Fig. 1Experimental procedure and testing schematic

a) Microhardness test lattice

b) Tensile specimen size (unit: mm)

c) Experimental process. Photos taken by Liu Pinxiao in Nanyang on 1 January 2025

3. Results and discussion

To systematically explore the influence law of laser welding speed on the quality of Q235 low-carbon steel welded joints, this study conducted characterization and analysis from five dimensions: macroscopic forming, microstructure, mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and friction and wear properties. The inherent correlation between welding speed and the comprehensive performance of the joints was fully revealed.

3.1. Macroscopic morphology analysis

Fig. 2 shows the macroscopic morphology of welded joints at different welding speeds. It can be seen from Fig. 2 that compared with traditional welding methods such as CO2 gas shielded welding, laser welding has no obvious protrusions in each welded joint due to its small heat input and high energy density, and the weld is narrow with a large depth-to-width ratio. Further observation shows that when the welding speed is 120 mm/min, the joint is burnt through, so it is used as a control group and no subsequent experiments are carried out; when the speed is 600 mm/min, the joint has the problem of incomplete penetration; the surfaces of the joints in the remaining groups are relatively smooth. Overall, when the welding speed is 300-500 mm/min, the joint morphology is the best and there are no welding defects.

Fig. 2Macroscopic morphologies of welded joints at laser welding speeds. Photos taken by Liu Pinxiao in Nanyang on 1 January 2025

a) 120 mm/min

b) 240 mm/min

c) 300 mm/min

d) 400 mm/min

e) 500 mm/min

f) 600 mm/min

3.2. Metallographic structure analysis

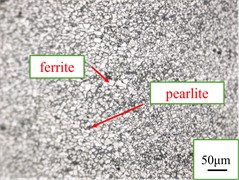

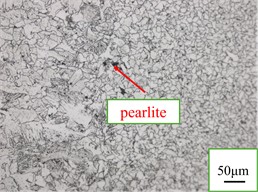

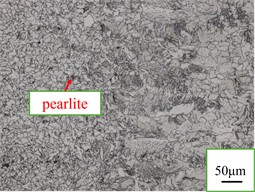

The welded joint is composed of three parts: the base metal zone, heat-affected zone (HAZ), and weld zone. Q235 is a steel that is not easy to harden by quenching [24], and its HAZ is further divided into three parts: the incomplete recrystallization zone, fine-grained zone, and coarse-grained zone. The metallographic microstructure of the Q235 steel base metal zone is mainly composed of ferrite and pearlite.

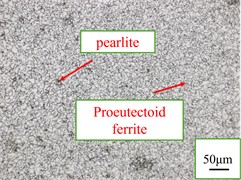

Fig. 3Incomplete recrystallization zones of welded joints at laser welding speeds. Photos taken by Liu Pinxiao in Nanyang on 10 January 2025

a) 240 mm/min

b) 300 mm/min

c) 400 mm/min

d) 500 mm/min

e) 600 mm/min

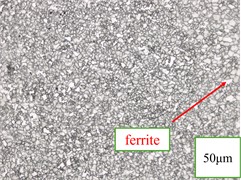

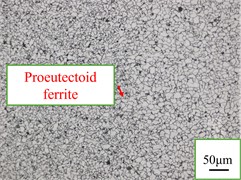

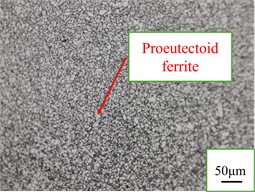

Fig. 3 shows the incomplete recrystallization zone of each welded joint. It can be seen from Fig. 3 that the structure of the incomplete recrystallization zone is mainly composed of ferrite, pearlite, and proeutectoid ferrite, with uneven grain size distribution. This is because only part of the structure in the incomplete recrystallization zone undergoes austenitization. During the cooling process, fine strip-shaped proeutectoid ferrite is formed before the eutectoid transformation, while the remaining part of the structure does not undergo austenitization, and the structure remains ferrite and pearlite after cooling.

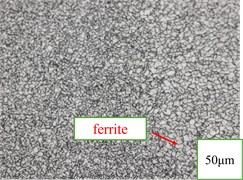

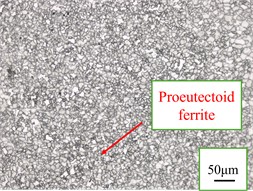

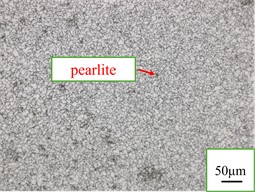

Fig. 4 shows the fine-grained zones of each welded joint. The fine-grained zone, also known as the normalizing zone, is observed to consist of proeutectoid ferrite and partial pearlite. The grain size in this zone is finer and more uniform compared to that in the incomplete recrystallization zone.

Fig. 4Fine-grained zones of welded joints at laser welding speeds. Photos taken by Liu Pinxiao in Nanyang on 10 January 2025

a) 240 mm/min

b) 300 mm/min

c) 400 mm/min

d) 500 mm/min

e) 600 mm/min

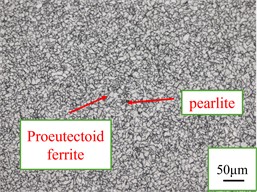

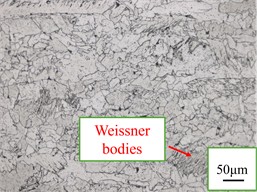

Fig. 5Coarse-grained zones of welded joints at laser welding speeds. Photos taken by Liu Pinxiao in Nanyang on 12 January 2025

a) 240 mm/min

b) 300 mm/min

c) 400 mm/min

d) 500 mm/min

e) 600 mm/min

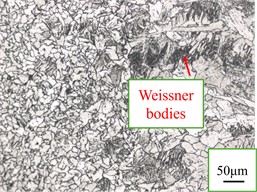

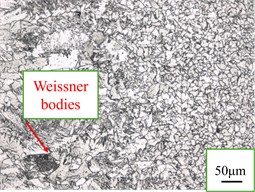

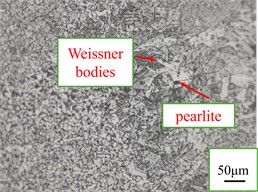

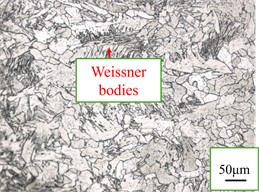

Fig. 5 shows the coarse-grained zones of each welded joint. As indicated in Fig. 5, the microstructure in the coarse-grained zone is primarily lumpy Widmanstätten structure with a small amount of pearlite. This occurs because the coarse-grained zone is closer to the weld during welding, resulting in higher peak temperatures and faster cooling rates. Acicular proeutectoid ferrite grows from the austenite grain boundaries into the grains, while austenite undergoes dynamic recrystallization, leading to coarse grain growth.

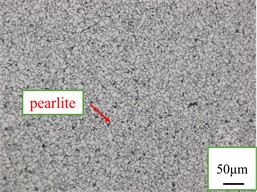

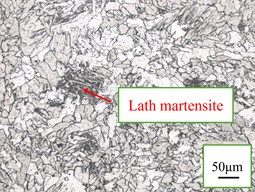

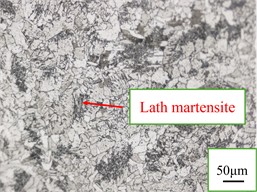

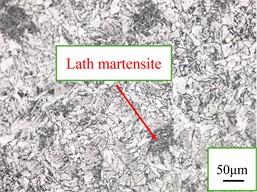

Fig. 6 shows the weld zones of each welded joint. As can be seen from Fig. 6, the metallographic structure of the weld zone mainly consists of feathery Widmanstätten structure and a small amount of lath martensite.

Fig. 6Weld zones of welded joints at laser welding speeds. Photos taken by Liu Pinxiao in Nanyang on 12 January 2025

a) 240 mm/min

b) 300 mm/min

c) 400 mm/min

d) 500 mm/min

e) 600 mm/min

Based on the metallographic structures of each zone at different laser welding speeds, it can be seen that with the increase of laser welding speed, the grain size in the weld zone gradually increases, and the contents of Widmanstätten structure and martensite also increase. The reason for this phenomenon is that with the increase of welding speed, the heat input per unit time decreases. Under the same cooling conditions, the faster the welding speed, the more conducive to the precipitation of carbon elements, and the greater the probability of forming martensite and Widmanstätten structure.

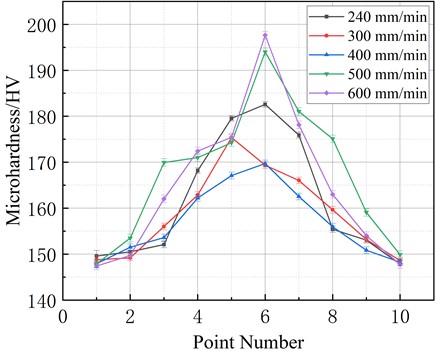

3.3. Microhardness analysis

The microhardness test curves are shown in Fig. 7, and the average hardness values of the weld zones for welded joints at different laser welding speeds are listed in Table 2. As observed, the hardness distribution patterns of welded joints under different welding speeds share similar trends: the hardness values of both the weld zone and heat-affected zone (HAZ) are higher than those of the base metal zone, with the weld zone exhibiting the highest hardness. This is because the fine-grained zone in the HAZ undergoes fine-grain strengthening, while the other two sub-zones (incomplete recrystallization and coarse-grained zones) are narrow, making them prone to being skipped by the lattice spacing during hardness testing. The presence of lath martensite in the weld zone further enhances the overall hardness of the welded area. The maximum hardness value recorded during the test was 197.64 HV, corresponding to the hardness of lath martensite. Additionally, the hardness of the HAZ decreases with increasing distance from the weld, showing a hard-to-soft transition. As indicated in Table 2, the hardness of the weld zone decreases at a welding speed of 300 mm/min, reaches the highest average value of 177.56 HV at 500 mm/min, and then decreases again at 600 mm/min.

Fig. 7Microhardness curves

Table 2Average hardness table

Laser welding speed (mm/min) | Average hardness of weld zone |

240 | 168.95 HV |

300 | 164.88 HV |

400 | 161.85 HV |

500 | 177.56 HV |

600 | 174.77 HV |

3.4. Tensile test analysis

Tensile tests were conducted on specimens obtained by wire cutting using a tensile testing machine. The fracture patterns of the tensile specimens are shown in Fig. 8. It can be seen that all fractures occurred in the base metal zone of Q235 steel rather than the weld zone, indicating that the tensile strength of the welds obtained at different laser welding speeds is higher than that of the Q235 base metal. Since the tensile specimens are of the same size, the fracture positions are similar, and all fractures belong to ductile fracture, it is indeed difficult to distinguish them.

Fig. 8Fracture effect diagrams of tensile specimens. Photos taken by Liu Pinxiao in Nanyang on 13 January 2025

a) 240 mm/min

b) 300 mm/min

c) 400 mm/min

d) 500 mm/min

e) 600 mm/min

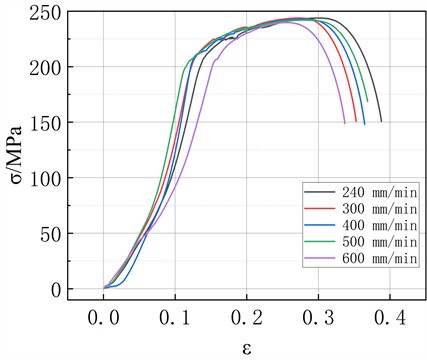

Tensile strength and elongation are two key indicators for measuring elastic materials. Generally, the greater the tensile strength, the smaller the elongation. The tensile strengths of tensile specimens under different laser welding speeds obtained by the tensile testing machine are shown in Table 3, and the mechanical property curves are shown in Fig. 9. As can be seen from Table 3, the tensile strengths of the welded joints obtained at the five different laser welding speeds are all higher than that of the base metal, and the elongation after fracture is lower than that of the base metal. Therefore, it can be known that after laser welding of Q235 steel, the tensile strength is improved to a certain extent, but the plasticity decreases. Among all the laser-welded specimens, the welded joint at a laser welding speed of 500 mm/min has the highest tensile strength (425.94 MPa), and its average elongation is the smallest (30.9 %). During the welding process, the weld zone (WZ) and heat-affected zone (HAZ) undergo intense temperature fluctuations, which causes the tensile strength of the weld zone to be higher than that of the base metal. The heat-affected zone of Q235 steel is divided into three regions: the incomplete recrystallization zone, the fine-grained zone, and the coarse-grained zone. Among them, the coarse-grained zone is close to the weld and experiences a high peak temperature, leading to abnormal growth of austenite grains and the formation of coarse Widmanstätten structure [25], which significantly weakens the grain boundary strength. In the incomplete recrystallization zone, the grain size is uneven, and ferrite and pearlite are distributed in a mixed manner, resulting in uneven stress distribution and making this zone a weak link in load-bearing. When the welding speed is too low (e.g., 120 mm/min), excessive heat input causes burn-through of the steel plate, forming welding defects. When the speed is too high (e.g., 600 mm/min), insufficient heat input leads to incomplete penetration. Both cases directly reduce the effective load-bearing area of the joint (Manuscript). Although no obvious defects are formed at a medium speed (300-500 mm/min), the cooling rate is still too fast, resulting in insufficient phase transformation and residual internal stress. The rapid heating and cooling during laser welding cause a difference in thermal expansion between the weld zone and the base metal, forming residual tensile stress [23].

Table 3Tensile test results of specimens at different welding speeds

Laser welding speed (mm/min) | Average tensile strength (MPa) | Average elongation |

0 | 421.27 | 33.7 % |

240 | 422.33 | 32.9 % |

300 | 424.68 | 32.1 % |

400 | 424.05 | 31.8 % |

500 | 425.94 | 30.9 % |

600 | 423.88 | 32.3 % |

Fig. 9Stress-strain diagrams at different welding speeds

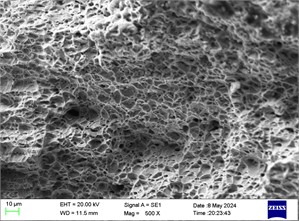

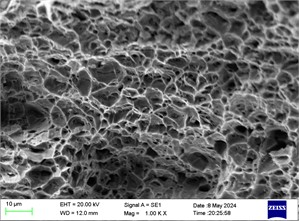

There are two conventional fracture modes: ductile fracture and brittle fracture. During ductile fracture, necking occurs at the fracture site, which appears as dimpled patterns under an electron microscope. The fracture surface of the tensile specimen was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Fig. 10 shows the SEM image of the fracture surface of the specimen welded at 500 mm/min. As observed in Fig. 10, the fracture site exhibits dimpled patterns. Combined with the obvious necking phenomenon in all tensile specimens shown in Fig. 8, this indicates that the fracture is a typical ductile fracture [26]. The dimples on the fracture surface of the Q235 steel weld zone are relatively shallow and unevenly distributed, which indicates that the energy absorbed during the growth and coalescence of microvoids is limited, and the plastic deformation capacity of the material is insufficient. This indirectly reflects the microscopic essence of the relatively low tensile strength of the welded joint. The failure of Q235 steel welded joints follows the typical ductile fracture path of “stress concentration - microvoid nucleation - growth and coalescence – fracture” [23].

Fig. 10SEM image of tensile specimen fracture surface at welding speed of 500 mm/min

a) 500X

b) 1000X

3.5. Electrochemical test analysis

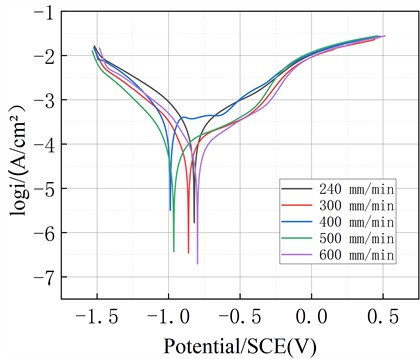

The polarization curves of welded joints and Q235 base metal in a 3.5 % sodium chloride solution were measured via potentiodynamic polarization at various laser welding speeds, as shown in Fig. 11. It is generally recognized that materials with higher corrosion potential and lower corrosion current density exhibit better corrosion resistance [27], with corrosion current density taking precedence over corrosion potential. The polarization curves were analyzed using the extrapolation method, and the calculated results are presented in Table 4.

Fig. 11Polarization curves

As shown in Table 4, when the laser welding speed is lower than 300 mm/min, the corrosion current density of the welded joints is higher than that of the base metal. The minimum corrosion current density (1.41×10⁻5 A/cm2) is observed at a welding speed of 500 mm/min, indicating the best corrosion resistance of the joint. When the welding speed exceeds 500 mm/min, the corrosion current density increases, suggesting a decline in corrosion resistance.

Table 4Corrosion current density and corrosion potential of each specimen

Welding speed | Corrosion current density (A/cm2) | Corrosion potential (V) |

0 mm/min | 2.36   10-5 10-5 | –0.513 |

240 mm/min | 3.04   10-5 10-5 | –0.796 |

300 mm/min | 4.47   10-5 10-5 | –0.648 |

400 mm/min | 1.51   10-5 10-5 | –1.028 |

500 mm/min | 1.41   10-5 10-5 | –1.031 |

600 mm/min | 2.54   10-5 10-5 | –0.715 |

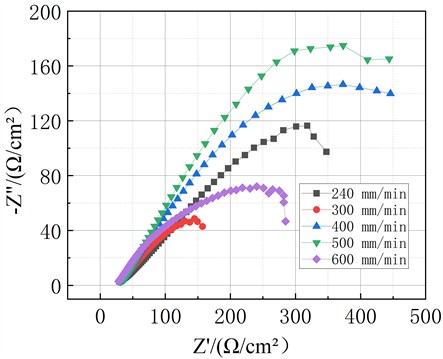

Impedance tests under open-circuit potential were conducted on each specimen, and the capacitance arc plots are shown in Fig. 12. The welded joint at 500 mm/min exhibits the largest capacitance arc radius, while the joint at 300 mm/min shows the smallest radius. Since the capacitance arc radius is proportional to impedance, and a higher impedance implies better corrosion resistance [28], the joint at 500 mm/min demonstrates the best corrosion resistance, which is consistent with the results from polarization curve measurements.

Fig. 12Impedance curves

3.6. Friction and wear test analysis

Friction and wear tests were conducted on welded joints at different laser welding speeds. Table 5 records the mass of each welded joint before and after the test. It can be seen from the table that the welded joint with a welding speed of 500 mm/min has the smallest mass difference before and after the test, proving that its wear amount is the least; while the welded joint with a welding speed of 300 mm/min has the largest mass difference, proving that its wear amount is the largest.

Table 5Mass of each welded joint before and after the test

Welding speed (mm/min) | 240 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 |

Mass before test (g) | 3.436 | 3.529 | 3.527 | 3.622 | 3.055 |

Mass after test (g) | 3.404 | 3.482 | 3.498 | 3.597 | 3.012 |

Wear mass (g)) | 0.032 | 0.047 | 0.029 | 0.025 | 0.043 |

The friction coefficient, defined as the ratio of frictional force to applied load, is related to material surface hardness, morphology, roughness, etc. A smaller friction coefficient indicates better wear resistance [29]. During the friction and wear test, the friction coefficient fluctuated significantly and generated substantial noise within the initial 600 seconds, attributed to the uneven surface of the welded joint. After 600 seconds, the friction coefficient stabilized. The friction coefficient of the Q235 base metal under 100 N was 0.675, while the average friction coefficients of welded joints at different laser welding speeds are listed in Table 6.

Table 6Average friction coefficients of each welded joint

Laser welding speed (mm/min) | 240 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 |

Average friction coefficient | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.60 |

As shown in Table 6, the average friction coefficients of all welded joints are lower than that of the Q235 base metal, indicating that the wear resistance of welded joints at different laser welding speeds is better than the base metal. The highest average friction coefficient (0.61) is observed in the joint welded at 300 mm/min, while the lowest (0.57) occurs at 500 mm/min. Comparatively, the welded joint at 500 mm/min exhibits the best wear resistance, whereas the joint at 300 mm/min shows the poorest performance.

4. Conclusions

This experiment conducted laser welding on Q235 steel at different speeds, and systematically tested the hardness, mechanical properties, corrosion resistance and wear resistance of the joints using an electrochemical workstation and high-speed wear tester. The conclusions are as follows:

1) The welds showed good formation. Welding speed did not significantly alter the microstructure type in each joint zone, but grain size increased with higher speeds.

2) All tensile specimens fractured in the base metal, indicating that the tensile strength of the welded joints exceeded that of the base metal, fluctuating around 424 MPa. Ductility decreased with increasing welding speed. SEM observation of the fracture surface revealed a honeycomb morphology and obvious necking, typical of ductile fracture.

3) The weld microstructure contained lath martensite, with the highest hardness in the weld zone. At a welding speed of 500 mm/min, the weld hardness reached 177.56 HV.

4) The welded joint at 500 mm/min had the lowest corrosion current density (1.41×10⁻5 A/cm2) and the largest capacitive arc radius (highest impedance), demonstrating optimal corrosion resistance.

5) The average friction coefficients of all welded joints were lower than that of the base metal. The joint at 500 mm/min exhibited the smallest friction coefficient (0.57) and minimum wear mass, indicating the best wear resistance.

6) In conclusion, the welded joints obtained at a laser welding speed of 500 mm/min exhibit the optimal comprehensive performance.

References

-

S. Li et al., “A novel beam shaping method for adjustable focus Gaussian-ring mode laser in high-quality welding process,” Optics and Laser Technology, Vol. 190, p. 113180, Nov. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2025.113180

-

R. Zhao et al., “Ethanol liquid film-assisted nanosecond laser transmission welding for stainless steel and glass,” Journal of Manufacturing Processes, Vol. 149, pp. 785–803, Sep. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2025.06.010

-

Q. Wei et al., “Quantifying the absorptivity in laser additive manufacturing and welding of aluminum alloy in the conduction mode,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology, Vol. 342, p. 118912, Aug. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2025.118912

-

R. Aslam, Q. Wang, J. Aslam, M. Mobin, C. M. Hussain, and Z. Yan, “Effect of temperature, and immersion time on the inhibition performance of Q235 steel using spent coffee grounds derived carbon quantum dots: Electrochemical, spectroscopic and surface studies,” Biomass and Bioenergy, Vol. 200, p. 107961, Sep. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2025.107961

-

Y. Chen, K. Huo, S. Huang, and F. Dai, “Research on laser modification of Q235 steel phosphate layer to improve paint adhesion and corrosion resistance,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 485, p. 141914, Jul. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.141914

-

X. Ren, W. He, J. Liu, and Y. Liu, “Experimental investigation of the corrosion behavior of Q235 steel in ethanol-gasoline blends,” Chemical Engineering Science, Vol. 313, p. 121731, Jul. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2025.121731

-

X. Cheng et al., “Experimental and numerical simulation study on T2/Q235 composite impact welded with various thickness of Zn interlayer,” International Journal of Material Forming, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 2129–2156, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-025-01903-w

-

X. Zheng and Y. Ding, “Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure and Properties of 304/Q235 Composite Round Steel,” Materials, Vol. 18, No. 11, p. 2497, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18112497

-

C. Bao et al., “Improved corrosion inhibition effect of a green three-component compound to Q235 steel in acidic solution,” Results in Chemistry, Vol. 15, p. 102316, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rechem.2025.102316

-

F. Cao et al., “Analysis of Corrosion Behavior Transition of Q235 Mild Steel with the Ionic Concentration in Oil Production Water Simulation Solutions,” Corrosion, Vol. 81, No. 5, pp. 432–442, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.5006/4665

-

Y. Wu, X. Gao, D. Zhang, and P. Gao, “Detection of Q235 mild steel resistance spot welding defects based on EMD-SVM,” Metals, Vol. 15, No. 5, p. 504, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/met15050504

-

Z. Hu, F. Yi, and H. Yu, “Synthesis and application of idesia oil-based imidazoline derivative as an effective corrosion inhibitor for Q235 steel in hydrochloric acid medium,” RSC Advances, Vol. 15, No. 17, pp. 13431–13441, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra09103e

-

C. Yu, G. Ren, Y. Huang, and M. Gao, “Study on process characteristics and microstructure-property of scanning laser hot-wire welding for Q235 stee,” (in Chinese), Chinese Journal of Lasers, Vol. 51, No. 12, p. 1202106, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3788/cjl230893

-

J. Li, “Research on laser-CMT hybrid welding process of D406A ultra-high strength steel,” Aerospace Propulsion Technology Institute, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.27848/d.cnki.ghtdl.2023.000006

-

Z. Jia, S. Yang, and Y. Qin, “Study on fiber laser welding process of 6061 aluminum/Q235 steel dissimilar metals,” Applied Laser, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 448–455, Aug. 2019, https://doi.org/10.14128/j.cnki.al.20193903.448

-

R. Safdarian, M. Sheikhi, and M. J. Torkamany, “An investigation on the laser welding process parameter effects on the failure mode of tailor welded blanks during the formability testing,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 28, pp. 1393–1404, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.12.061

-

W. Xie, H. Tu, K. Nian, and X. Zhang, “Microstructure and mechanical properties of laser beam welded 10 mm-thick Q345 steel joints,” Welding International, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 34–44, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1080/09507116.2023.2281502

-

S. Afkhami, M. Ghafouri, K. Lipiäinen, I. Poutiainen, M. Amraei, and T. Björk, “Effects of laser welding speed on the microstructure and microhardness of ultra-high strength steel S1100,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 1296, No. 1, p. 012025, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1296/1/012025

-

K. Vamsi Krishna, S. Rowthu, V. N. Nadakuduru, G. Pilla, and N. Kishore Babu, “Effect of welding speed and postweld heat treatment on microstructural characterization and mechanical properties of gas tungsten arc welded Ti-15V-3Al-3Cr-3Sn joints,” Fusion Science and Technology, Vol. 80, No. 1, pp. 68–81, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1080/15361055.2023.2182119

-

L. Y. Narayan, V. Bhanu, S. Sirohi, S. Kumar, D. Fydrych, and C. Pandey, “Microstructure anomaly due to the heat from the laser welding process and its effect on the mechanical behavior of the dissimilar welded joint between P92 steel and Inconel 625 for AUSC boiler applications,” The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, Vol. 140, No. 3-4, pp. 2129–2156, Aug. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-025-16361-6

-

L. Y. Narayan, C. Dangi, H. Natu, S. Sirohi, S. M. Pandey, and C. Pandey, “Autogenous laser welded joint of Inconel 625 and AISI 316L steel: Microstructure and mechanical properties,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications, Jul. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/14644207251355874

-

D. Moulali et al., “Laser welding on 10 mm thick grade 92 steel for USC applications: microstructure and mechanical properties,” Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 25, No. 2, p. 90, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-025-01144-3

-

C. Pandey, N. Saini, M. M. Mahapatra, and P. Kumar, “Study of the fracture surface morphology of impact and tensile tested cast and forged (C&F) Grade 91 steel at room temperature for different heat treatment regimes,” Engineering Failure Analysis, Vol. 71, pp. 131–147, Jan. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2016.06.012

-

L. Zhou, R. Zhang, F. Shu, Y. Huang, and J. Feng, “Analysis of microstructure and mechanical properties of friction stir welded joints of Q235 steel,” Transactions of the China Welding Institution, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 80–84, Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.12073/j.hjxb.2019400076

-

C. Pandey, M. M. Mahapatra, P. Kumar, F. Daniel, and B. Adhithan, “Softening mechanism of P91 steel weldments using heat treatments,” Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 297–310, Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acme.2018.10.005

-

Y. Liu, J. Chen, G. Guo, J. An, and H. Chen, “Effect of Element on Porosity and Residual Stress Distribution of A7N01S-T5 Aluminum Alloy Welded Joints in High-Speed Trains,” Residual Stresses 10, Vol. 2, pp. 503–508, Jan. 2017, https://doi.org/10.21741/9781945291173-85

-

D. Lin, G. Gu, and J. Shang, “Effect of laser remelting treatment on microstructure and properties of micro-arc oxidation coating on aluminum alloy,” (in Chinese), Heat Treatment of Metals, Vol. 48, No. 4, pp. 264–272, Apr. 2023, https://doi.org/10.13251/j.issn.0254-6051.2023.04.041

-

Y. Xu, J. Li, M. Shi, P. Qian, and L. Peng, “Microstructure and mechanical properties of laser-welded joints of Q235/304 dissimilar steels,” (in Chinese), Applied Laser, Vol. 42, No. 4, pp. 21–28, Apr. 2022, https://doi.org/10.14128/j.cnki.al.20224204.021

-

C. Chen, L. Liu, Y. Tian, and Q. Li, “Study on impact and coupling friction-wear behavior of Q235 steel,” (in Chinese), Journal of Xuzhou University of Technology, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 48–50, Mar. 2010, https://doi.org/10.15873/j.cnki.jxit.2010.01.005

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Liu Pinxiao: writing-review and editing. Liu Deping: data curation. Cai Guangyu: software. Yan Jisen: software, writing-review and editing. Liu Zhenyang, Liu Haonan and Li Kai: writing-original draft preparation.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.