Abstract

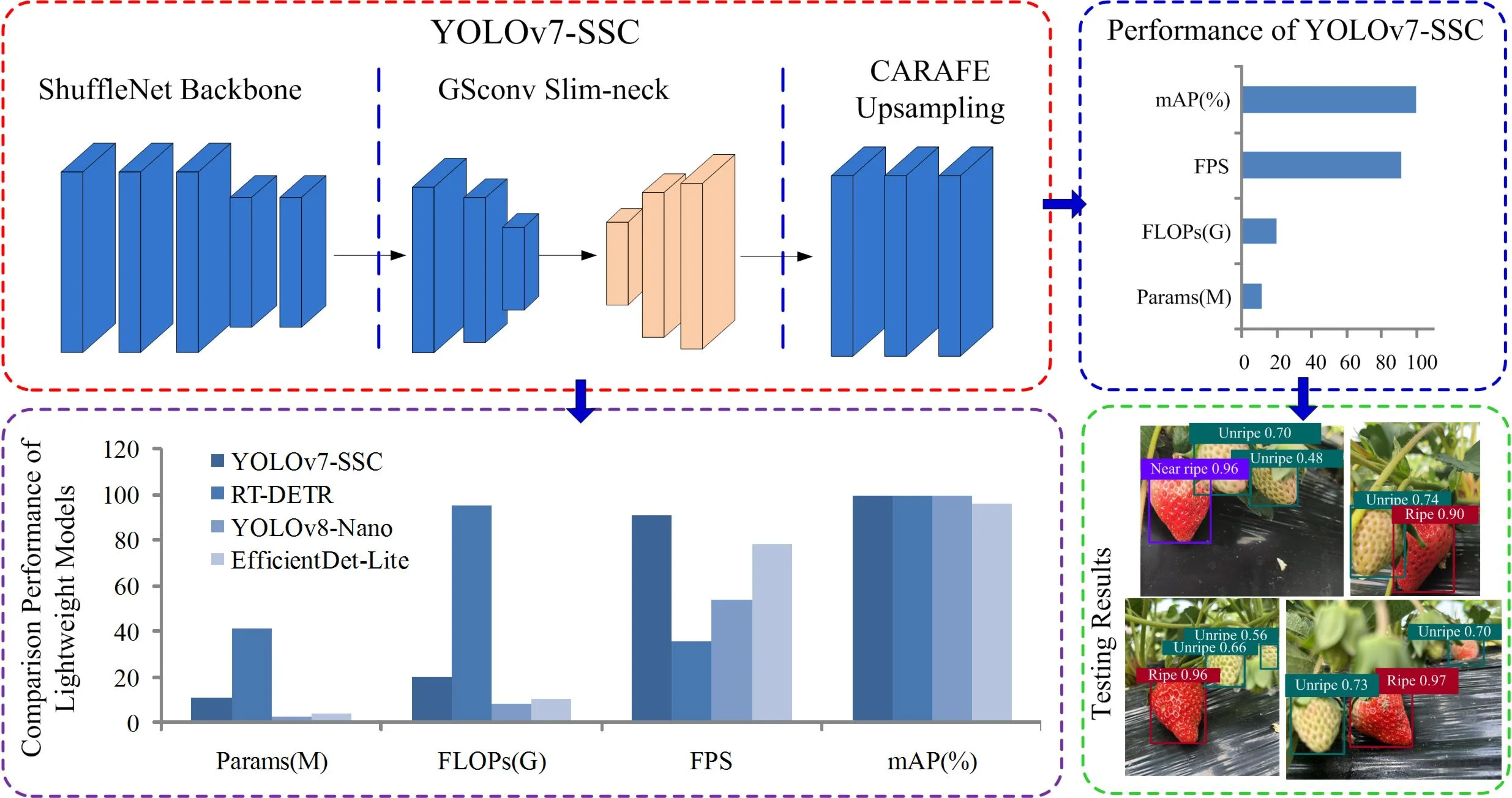

To address inaccurate strawberry recognition caused by cluttered field environments such as varying illumination, occlusion and uneven distribution, an improved lightweight model YOLOv7-SSC for strawberry ripeness detection was proposed. First, the backbone network of YOLOv7 is replaced with ShuffleNetV2, a lightweight feature extraction network, to significantly reduce the number of model parameters. Second, the lightweight network Slim-neck is used as the neck structure to reduce model complexity while preserving high precision. Finally, the Content Perception Feature Recombination (CARAFE) upsampling is used to enlarge receptive field in the feature fusion network and fully leverage semantic information. Moreover, the pictures of the strawberry dataset with three common conditions (unripe strawberry, near ripe strawberry and ripe strawberry) were collected in real picking environment. The experimental results show that compared to the original YOLOv7 model, the improved model parameters are reduced by 69.0 %, the floating point number is decreased by 79.4 %, and the accuracy rate reaches 99.6 %. These results demonstrate that YOLOv7-SSC model can achieve fast recognition of strawberry maturity while maintaining high precision, making it more suitable for small target detection in complex field compared with other algorithms.

Highlights

- An improved lightweight YOLOv7-SSC model is proposed for strawberry ripeness detection in cluttered fields, replacing YOLOv7’s backbone with ShuffleNetV2, adopting Slim-neck as neck structure and CARAFE for upsampling to cut model complexity while retaining precision.

- YOLOv7-SSC achieves superior lightweight performance and detection accuracy: 69.0% fewer parameters, 79.4% lower FLOPs than original YOLOv7, with mAP@0.5 reaching 99.6% and FPS up to 90.91.

- Compared with EfficientDet-Lite, YOLOv8-Nano and RT-DETR, YOLOv7-SSC strikes the best balance of speed, accuracy and lightweight design, accurately detecting small, occluded strawberries in complex field environments.

1. Introduction

Strawberries are widely cultivated worldwide due to their appealing taste, high nutritional value, and edibility. As a crucial element in strawberry cultivation, the harvesting of strawberries still depends on hand labor, making up more than 75 % of the total cultivation expense [1]. Therefore, mechanized harvesting has become an inevitable trend for the development of strawberry industrial planting. However, due to the complex field environment, intelligently identify the maturity of strawberries is difficult.

Convolutional neural network (CNN), a representative algorithm of deep learning, performs consistently well in image recognition by extracting discriminative features from images in the presence of sufficient training data [2-5]. CNN can realize high precision recognition of two-dimensional image data [6-8]. In addition, the target detection task has been applied to a wide range of scenarios and has achieved good results. The multi-expert diffusion model, which integrates a Multi-Expert Feature Extraction module, a Low-Pass Guided Feature Aggregation module, and a Heterogeneous Diffusion Detection mechanism, enables high-precision detection of surface defects on motor control valve spools, improving accuracy by 6.1 % over special methods and ensuring the safe operation of electromechanical equipment [9]. Furthermore, the vision-language cyclic interaction mode, which progressively refines visual feature extraction by integrating domain prior knowledge and generic large model, effectively bridges the dual-domain barrier of “generic-specific” and “vision-language”, achieving high-precision defect detection while demonstrating strong validity and generalization across diverse scenarios [10]. One-stage object detection algorithm represented by YOLO series transforms the target detection task into a regression problem within a single neural network, achieving fast and accurate target localization and classification of strawberries in in cluttered field environment [11-13]. YOLOv5 algorithm and dark channel image enhancement were combined to classify strawberry maturity into three levels: ripe, near ripe and immature [14]. Two-stage, represented by Faster-RCNN, is usually more accurate than One-stage algorithm, but the detection speed is slower [15]. The fast and stable target recognition system can enable the picking robot to work effectively for a long time, which greatly improves the picking efficiency. Domestic and foreign scholars have made a preliminary exploration on the research of strawberry ripeness recognition [16].

The integration of deep learning with traditional digital image processing and segmentation can achieve more effective and accurate fruit detection and classification [17]. The ellipsoidal Hough transform segmentation algorithm is used to automatically segment strawberry images, and Probabilistic Soft Logic (PSL) model is adopted to predict strawberry sweetness and acidity according to the ripening stage [18]. The convolutional neural network of an automated system is used to extract the color, size and shape features of the surface of the strawberry to determine whether the strawberry is ripe or damaged, and the classification output and classification image are displayed on the Graphical User Interface (GUI) [19]. According to a dual-path model which learns strawberry ripen and stem coordinates simultaneously through semantic segmentation, the feature maps acquired at the final part of the multi-path convolution segmentation model is used for two ways: one path is used for semantic segmentation learning to determine strawberry maturity, and the other path is used for key point segmentation to detect strawberry stem [20]. Since individual frames are enhanced with depth information to determine the strawberry position by providing live video as input, the fast and accurate detection system based on neural networks can be used to detect strawberries for a large-scale harvest [21]. However, strawberries are easily blocked by soil, branches and leaves, and a large number of strawberries with similar colors are gathered to cause clustering, overlapping, blocking and other phenomena resulting in difficult strawberry target detection [22].

Therefore, some aspects should be considered in the strawberry recognition process: first, when the target is overlapped and blocked, it is difficult to distinguish through the shape information of the detection target because of the difference of strawberry shape; second, due to the surface texture of strawberries affected by illumination, shadow and other factors, the brightness and color of strawberries in the image are different, thus influencing the recognition result; third, since the background of strawberry recognition is complicated, the texture and color information of strawberry fruit is often confused with the interference information such as soil and green leaves, interfering with the accuracy of recognition. Due to the above differences, the existing target recognition strategies are difficult to be directly applied to strawberry recognition. The literature remains sparse regarding rapid and intelligent classification and detection of strawberry ripeness.

YOLOv7, released in 2022, offers superior detection accuracy and fast inference due to its complex architecture and training strategy [23-25]. The field of lightweight detection has since advanced, with newer models like YOLOv8 [26], RT-DETR [27], and PP-YOLOE [28] pushing the boundaries of performance and efficiency. Despite their general excellence, these state-of-the-art models often struggle with specialized agricultural tasks, such as detecting small, occluded strawberries in cluttered environments. The complexity of these newer architectures can also hinder their adaptation for resource-constrained deployment. Consequently, the robust and well-established YOLOv7 framework serves as a practical foundation. By integrating advanced lightweight modules into YOLOv7, a model can be created that is specifically optimized for strawberry detection, achieving a fine-tuned balance of accuracy, speed, and efficiency. This rationale underpins the proposal of YOLOv7-SSC, a lightweight model built upon the YOLOv7 framework for strawberry ripeness detection. The following is the main content of the paper:

1) The original YOLOv7 backbone is replaced with ShuffleNetV2 to reduce the model’s computational burden.

2) Lightweight network Slim-neck is selected as the neck structure of the improved model, which can not only reduce the complexity of the model, but also better retain information and improve the detection accuracy.

3) The upsampling operator of CARAFE enables us to extract information more completely from images by expanding the perceptual field of view, thus enhancing the detection accuracy of small objects.

The rest of this article is organized as follows: The second section introduces the image data collection and dataset construction; the third section introduces the improved lightweight model YOLOv7-SSC; the fourth section introduces the experiments; in the fifth section, results are discussed and analyzed; the sixth section summarizes the research methods. Moreover, this paper establishes strawberry data set in complex environment, adopts YOLOv7 detection network model, and improves and optimizes algorithm model according to problems existing in data samples, providing research basis for mechanized picking of ripe strawberries.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Image data collection

The experimental images were acquired from a strawberry plantation in Xinhua Village, Huainan City, Anhui Province, China, during the harvest period from March 1 to March 10, 2023, by Yuanmeng Wang, Xinyi Chen and Ruoqi Wu. The strawberry plantation is cultivated in a land-based ridge pattern, and the main strawberry varieties include “Hong Yan” and “Feng Xiang”, which are characterized by the reddish color, large size, and full-fleshed fruits. To ensure a comprehensive and balanced dataset, 3000 JPEG images with 4000×3000 resolution were collected, with 1000 images each for unripe, near-ripe, and ripe strawberries. To account for lighting and environmental changes, all images were randomly acquired at different times of day (morning, noon, afternoon) across various weather conditions. The distribution of the image dataset is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1Detailed distribution of the strawberry image dataset

Maturity stage | Number of images | Acquisition time | Weather condition | |||

Morning | Noon | Afternoon | Sunny | Cloudy | ||

Unripe | 1000 | 347 | 295 | 358 | 693 | 307 |

Near-ripe | 1000 | 408 | 247 | 345 | 758 | 242 |

Ripe | 1000 | 295 | 352 | 353 | 801 | 199 |

Total | 3000 | 1050 | 894 | 1056 | 2252 | 748 |

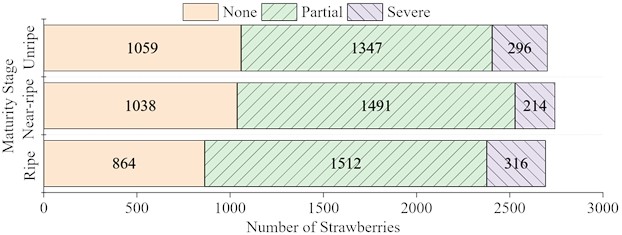

The collection intentionally includes instances of partial and severe occlusion obtained through different shooting angles (top-down, side-view, and oblique). To quantify the occlusion levels of strawberries in the acquired image dataset, three levels of occlusion for each strawberry were defined based on the visible proportion of the fruit: None (over 90 % of the fruit is visible with a clear contour), Partial (between 50 % to 90 % is visible, allowing for confident maturity assessment), and Severe (less than 50 % is visible, making maturity challenging to determine). The occlusion status of strawberries in the dataset was cross-validated by three independent annotators to adhere strictly to these criteria shown in Fig. 1.

2.2. Dataset construction and annotation

The strawberry image dataset was divided into training and validation sets in the proportion of 8:2. The detection targets focus on three ripening stages: unripe, near-ripe, and ripe strawberries, as shown in Fig. 2.

LabelImg is an open-source graphical image annotation tool designed for manual object detection labeling. It supports the creation of both rectangular bounding boxes (ideal for marking the position and size of regular objects) and polygonal annotations (suitable for irregularly shaped objects). Using this tool, the corresponding XML files were generated to record strawberry locations and their associated category information, thereby building a high-quality strawberry dataset.

To ensure annotation consistency, all annotations were cross-validated by three annotators, guided by different professional growers at the plantation, and ambiguous cases were resolved through group discussion. A subset of 300 images was re-annotated by a second annotator, achieving an inter-annotator agreement (as measured by IoU) of 0.92, indicating high labeling consistency.

Fig. 1Occlusion levels of strawberries in the dataset

Fig. 2Examples of acquired strawberry pictures in different ripeness states. Photos were taken in Xinhua Village, Huainan City, Anhui Province, China, from March 1 to March 10, 2023, by Yuanmeng Wang, Xinyi Chen, and Ruoqi Wu

3. An improved lightweight model for strawberry detection

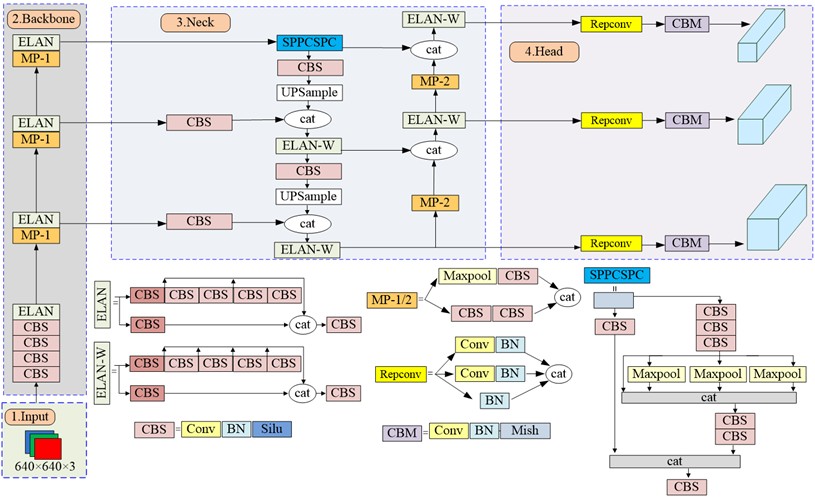

3.1. Overview of the original YOLOv7 network structure

YOLOv7 has outperformed known detectors such as YOLOv5 for velocity and precision. Since YOLOv7 uses faster convolution operations and smaller models, it can achieve high-precision results in a short time during detection. The overall network architecture of YOLOv7 is shown in Fig. 3, which includes input layer, backbone layer, neck layer and head layer. The preprocessed images are input to the backbone layer for feature extraction which is head-fused to acquire features at different size. Finally, the detection results are output by the detection head after receiving the fused features.

The YOLOv7 network model primarily consists of three main parts: Backbone (based on CSPDarknet53), Neck (featuring Path Aggregation Feature Pyramid Network, PAFPN), and Head. Key modules include the Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (ELAN) module, the MaxPool convolution (MP-1) module, and the Spatial Pyramid Pooling Cross Stage Partial (SPPCSPC) module [29].

The CBS module is a basic convolution module, consisting of asynchronously long convolution, which contains convolution, batch normalization, and activation functions. The ELAN module is an efficient network architecture composed of multiple CBS modules, which enhances the learning capability of the network while preserving the integrity of the original gradient paths. The MP-1 module is a subsampling module composed of two branches of the same length, one part is composed of MaxPool and CBS modules, and the other part is composed of two CBS modules. The MP-1 module aims to preserve feature information while reducing the number of parameters during the downsampling process. SPPCSPC module is an improved spatial pyramid pooling structure, which adds concurrent MaxPool operations to convolution. The PAFPN used by the Head layer realizes the efficient fusion of features at various degrees by introducing a bottom-up path [30]. The Reparameter Convolution (Repconv) module is used to acquire further feature information [31].

Fig. 3Network architecture of the original YOLOv7 model. BN is the Batch normalization; Silu and Mish are activation functions; UPSample denotes resizing the feature map using nearest-neighbor interpolation

3.2. Enhanced module design

3.2.1. ShuffleNetv2 backbone

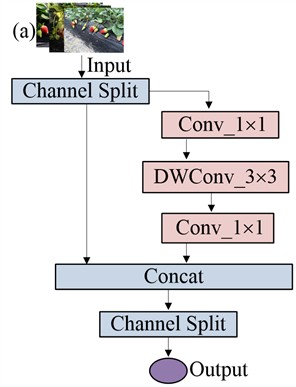

The YOLOv7 backbone network is based on the CSPDarknet53 architecture. Because this two-branch structure contains too many convolutional layers, the number of parameters is too large, which seriously affects the detection rate. Hence, in the study, in order to decrease computational requirements and the required storage space, the network ShuffleNetv2 is used to replace the YOLOv7 backbone network.

The main improvement in ShuffleNetv2 [32] is the channel shuffle operation, which enables efficient exchange of information between different channel groups, which enhances the network's ability to capture space and channel dependencies. ShuffleNetv2 also utilizes depth-separable convolution, splitting the convolution operation into separate deep and point-by-point convolution. This operation decreases arithmetic complexity of the network while preserving its expressiveness.

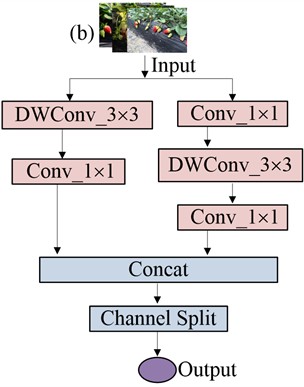

ShuffleNetv2 uses a new operation Channel Split shown in Fig. 4. When the step length is 1, ShuffleNetv2 uses Channel Split to divide the original channel number into two parts, and the left one is not processed shown in Fig. 4(a). The right branch consists of two normal convolution and one depth-wise convolution (DWConv) operation, after which ShuffleNetv2 splices the two branches together to reduce element-level operations, and finally mixes the channels with Channel Shuffle. When the step size equals to 2, the input data separated into two parts, both of which use DWConv to decrease the size of feature maps, thereby lowering the network's FLOPs shown in Fig. 4(b). After processing, the branches are concatenated to increase network width, with Channel Shuffle facilitating information exchange between channels.

Fig. 4ShuffleNetv2 base Units: a) Unit1 with stride = 1, which uses Channel Split to process features; b) Unit2 with stride = 2, which employs depth-wise convolution (DWConv) for downsampling

3.2.2. Introducing Slim-neck by GSConv in neck layer

Slim-neck by Ghost-Shuffle Convolution (GSConv) is a lightweight feature fusion module that reduces the detector's computational complexity and inference time by reducing the number of feature channels while maintaining accuracy[33-34]. In strawberry ripeness detection, because the target is usually small, the excessive number of feature channels will lead to the redundancy of the model and affect detection performance. Slim-neck can effectively reduce feature channels and increase detection rate and accuracy.

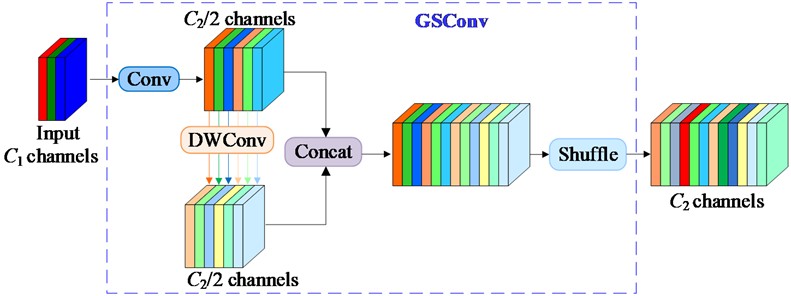

GSConv is the mixed convolution of channel standard convolution (SC), depth-wise separable convolution (DSC), and shuffle. When applied to the neck layer, the feature graph output from the backbone reaches its maximum channel dimension and minimum width and height. However, using GSConv would deepen the network, increase data flow resistance and reasoning time.

In the GSConv structure shown in Fig. 5, first of all, the input feature graph is convolved 3×3 to produce an intermediate output. Subsequently, the intermediate output is processed by DWConv. Then, the two outputs are formed a new feature graph through the concat operation. Finally, channel shuffling is performed using Shuffle operation to produce the output with channels.

Fig. 5The structure of GSConv module. GSConv is the Ghost-Shuffle Convolution; C1 is the number of channels of the input feature graph; C2 is the number of channels of the output feature graph

The calculation process is shown in Eq. (1):

where, is the output feature map after GSConv, is input feature graphs with channels, is the conventional convolution, and is DWConv.

The shuffle operation integrates the information produced by the SC into each part of the DSC output. By uniformly exchanging local feature information across different channels, SC information is thoroughly mixed into the DSC output without any additional functions.

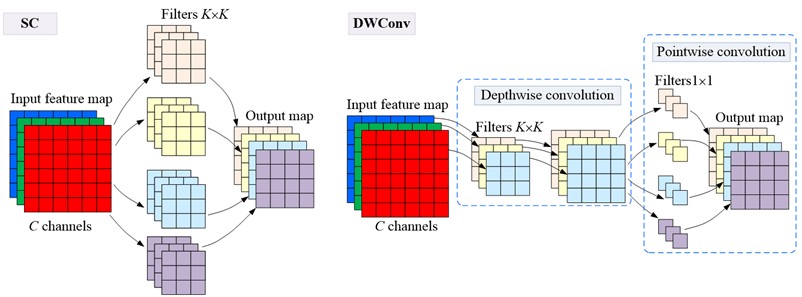

The standard convolution is to multiply each channel data and the corresponding channel of the filter element by element and add it up, as displayed in Fig. 6. If the input data has C channels and the filter size is K3K, the standard convolution parameter is C3K3K. The DWConv is composed of the deep and the point-by-point convolution step. If the input data has channels and the filter size is K3K, the deep convolution parameter of DWC convolution is C3K3K, and the point-by-point convolution parameter is .

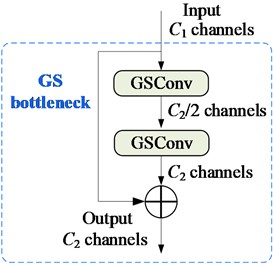

GSConv is used to replace SC, and continue to introduce Ghost-Shuffle bottleneck (GS bottleneck) on the basis of GSConv exhibited in Fig. 7(a). Preprocessed images are input to the backbone for feature extraction, which are then fused into large, medium, and small size features. These fused features are sent to the detection head to produce the detection results.

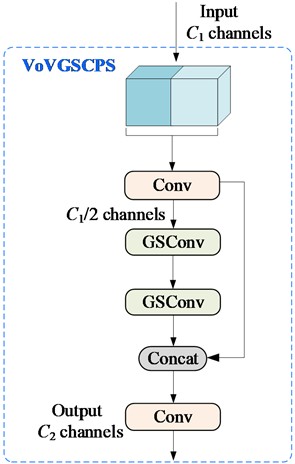

To reduce further model complexity, a one-time aggregation cross stage partial network (VoVGSCSP) module is designed using the clustering method based on ResNet, as illustrated in Fig. 7(b). First, a 1×1 convolution is adopted to extract input features, reduces channels by half, and then enter them into GS bottleneck. The first GSConv layer further halves the channels and outputs them through the second GSConv layer, resulting in channels of /2. Then, it bottlenecks the VoVGSCSP input with a 1×1 convolution and concats the GSBottleneck output. The final output is produced by another 1×1 convolution with channels.

Fig. 6Calculation processes of SC and DWConv. SC is standard convolution; C is the number of channels of the input feature map; K3K is the filter size

Fig. 7The structure of the GS bottleneck and VOVGSCSP: a) the structures of the GS bottleneck; b) the structures of the VOVGSCSP, where GS bottleneck is the Ghost-Shuffle bottleneck, and VoVGSCSP is one-time aggregation cross stage partial network module

a)

b)

3.2.3. CARAFE for feature fusion

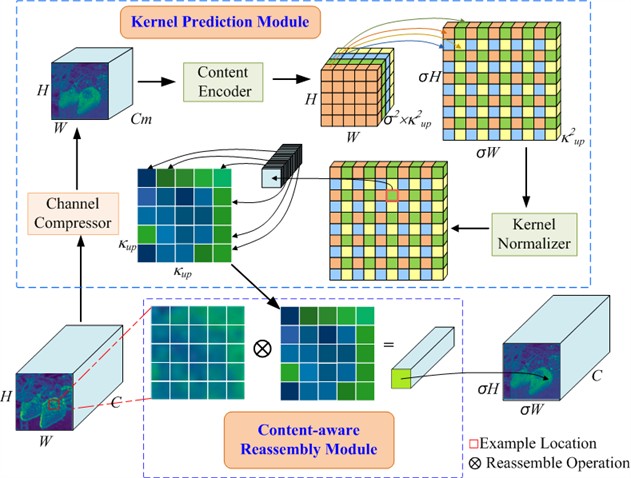

The upsampling method used by YOLOv7 is the nearest neighbor interpolation, however, this upsampling method only considers the subpixel neighborhood, and cannot capture the semantic information required for intensive prediction tasks. Usually, the perceptual domain is very small. However, the upsampling of Content Sensing Feature Recombination (CARAFE) can use the underlying content information to predict the recombination kernel. The feature is reassembled in the predefined nearby regions to ensure that the receptive field in the feature fusion network can be extended while the semantic information is fully utilized. The core idea of CARAFE is to use the content of the input feature itself to guide the upsampling process, so as to achieve more accurate and efficient feature reconstruction. CARAFE is composed of upsampling prediction module and feature recombination module [35-36].

Assuming that the upsampling rate is σ and an input feature graph with the shape of H3W3C is given, CARAFE first predicts the upsampled kernel with the upsampled kernel prediction module, and then completes the upsampled kernel with the feature recombination module to obtain the output feature graph with the shape of H3W3C, as shown in Fig. 8.

For the upsampling prediction module, the channel compression of the feature graph is firstly carried out, that is, the channel number of the input feature graph with size H3W3C is compressed to H3W3 by 1×1 convolution, and the convolution kernel is applied to carry out the convolution operation. Then content coding is carried out to generate the reassembled kernel, the number of input channels, output channels and the number of channels is extended to content coding; finally, the output is spatially normalized. In the feature recombination module, the corresponding position of the output feature map and the traditional feature map is dot product, and the output value is obtained.

Fig. 8Structure of CARAFE upsampling module. CARAFE is the upsampling of content sensing feature recombination; the input feature graph with size H3W3C is upsampled by a factor of σ

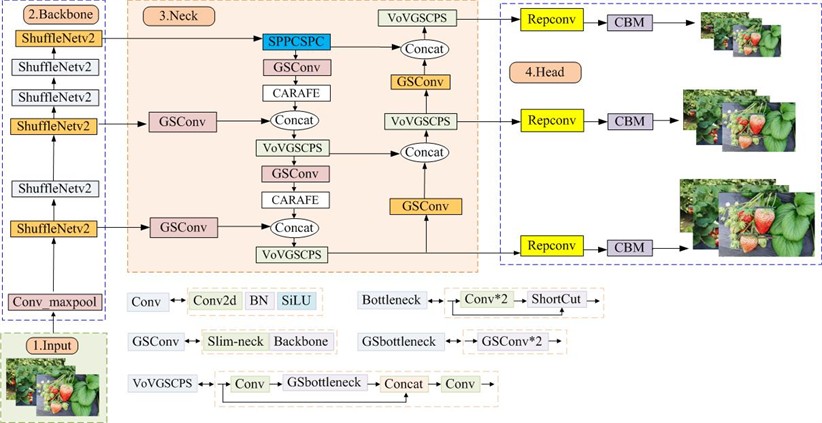

3.3. Integrated architecture: YOLOv7-SSC

The proposed YOLOv7-SSC framework addresses the limitations of vanilla YOLOv7 in handling occluded and densely clustered strawberries. The overall framework of the improved network structure YOLOv7-SSC is shown in Fig. 9. Key enhancements include the replacement of the original backbone with ShuffleNetV2, the integration of a Slim-neck with GSConv for efficient feature fusion, and the adoption of CARAFE for content-aware upsampling, collectively improving performance on occluded and clustered strawberries.

The input images are first preprocessed into 640×640 resolution RGB format and fed into the ShuffleNetV2 backbone network. The lightweight backbone network ShuffleNetV2 processes the images and outputs feature maps. The generated feature maps are then processed by the Slim-neck module, where GSConv replaces standard convolution. Afterward, CARAFE upsampling leverages semantic content to adaptively reassemble features, which are further processed by VoVGSCSP module to preserve fine-grained details. This design enhances the detection capability for small and occluded strawberries.

Fig. 9Architecture of the proposed YOLOv7-SSC network. The model incorporates ShuffleNetV2 as the backbone, a Slim-neck with GSConv, and a CARAFE upsampling module

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental environment configuration and parameter settings

The hardware environment of this paper uses RTX 3080 Ti graphics card with 12GB video memory and Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4214R CPU@2.40GHz. The software environment is Windows 11 operating system, the development environment is PyTorch 2.0.0, CUDA 11.8, and Python version 3.9.0. During the training, SGD optimizer was used to optimize the model. Iteration batches were 8, the initial learning rate was set to 0.001, and the input image resolution was 640×640. A total of 200 training cycles were conducted.

To mitigate overfitting and enhance the model’s generalization ability, a series of data augmentation techniques were applied to the training set using the PyTorch and OpenCV frameworks. These techniques included geometric transformations such as random rotation (±15 degrees) and horizontal flipping, as well as photometric adjustments like random brightness and contrast variations. This process effectively expanded the training dataset to about 5000 annotated images, simulating a wider range of real-world conditions, such as varying shooting angles and lighting environments.

The model was optimized using the SIoU (Scalable Intersection over Unio) loss function, which incorporates angle cost, distance cost, and shape cost into the bounding box regression, effectively decreasing the total degrees of freedom and leading to faster and more stable convergence. The learning rate was scheduled using a linear decay strategy, which gradually reduces the learning rate from the initial value of 0.001 to a final value of 0.00001 over the course of the 200 training epochs, ensuring a stable and consistent decline throughout the optimization process.

4.2. Model evaluation index

In this study, the effect of the model is tested mainly from the lightweight degree and recognition accuracy of the model, and the mean average precision (mAP), Giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPs), the frame per second (FPS) and Parameters are used as four indexes to evaluate the lightweight degree of the model. Specifically, the number of parameters (Params) was obtained by summing all trainable weights in the network, while the computational load (FLOPs) was calculated for a single forward pass using the ptflops library (version 2.0.0).

(1) AP indicator is the area under the PR curve and is used to describe the average accuracy of high ridge strawberry detection. Where TP (True Positive) is the number of samples that correctly detect the ripeness of strawberries, TN (True Negative) indicates the number of samples that are correctly detected as unripe strawberries, FP (False Positive) is the number of samples that incorrectly detect the ripeness of immature strawberries, and FN (False Negative) is the number of samples that incorrectly detect the ripeness of strawberries. The formula is as follows:

(2) GFLOPs is used to measure the complexity of the model, calculated as follows:

where and represents the number of input and output channels, represents the size of the kernel, and are used to describe the size of the feature map.

(3) The value of FPS is equal to the number of images processed by the model per second, which can be used to detect the model speed, and is the number of images processed by the model; is the time consumed. The formula is as follows:

(4) Parameters number refers to the number of parameters that the model contains.

5. Result and discussion

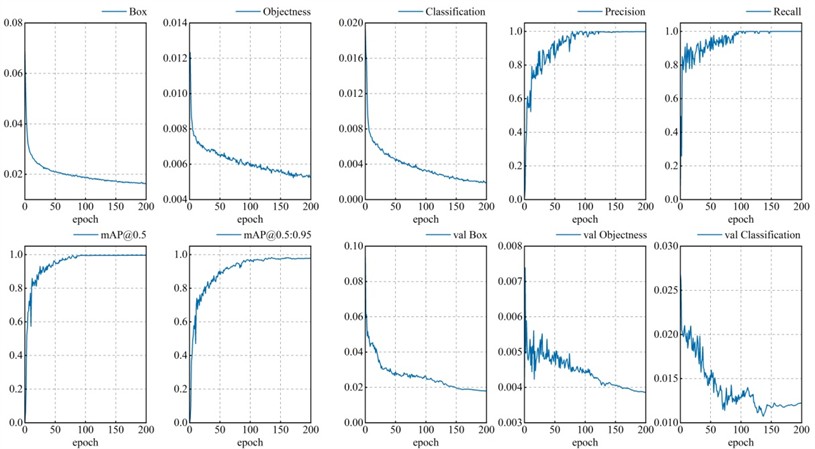

5.1. Training evaluation of YOLOv7-SSC model

All evaluation indexes tend to be stable after 150~200 epochs shown in Fig. 10. The training of the model ends when epoch reaches 200.

5.2. Experimental analysis of lightweight network

In order to achieve both accurate identification of strawberry maturity and model lightweight, it is also the most important thing to select the appropriate backbone network. Therefore, the YOLOv7 backbone network is replaced by the current mainstream lightweight network to detect the maturity of high-ridge strawberries. The main lightweight model structure is MobileNetv3 [37], ShuffleNetv2, GhostNet [38]. Each network model Params(M), FLOPs(G) and mAP are shown in Table 2.

As can be seen from Table 2, after adding ShuffleNetv2 network to the model, the number of parameters decreased by 46.2 %, FLOPs(G) decreased by 62.1 % and mAP did not decrease. Compared with other lightweight networks, the model with ShuffleNetv2 network has better accuracy and lower parameters. Therefore, ShuffleNetv2 network was chosen as the backbone network in this paper, which can reduce the complexity of the model while retaining the expressibility. Better detection results can be achieved with less computing resources.

Table 2Comparison of lightweight network models

Model | Params(M) | FLOPs(G) | mAP(%) |

YOLOv7 YOLOv7-MobileNetv3 | 37.2 23.4 | 105.1 37.4 | 99.6 97.6 |

YOLOv7-GhostNet | 26.7 | 53.3 | 96.5 |

YOLOv7-ShuffleNetv2 | 20.0 | 39.8 | 99.6 |

Fig. 10Evaluation index of YOLOv7-SSC model training process based on self-built datasets

5.3. Ablation experiments

The ablation experiment is necessary to check whether the modules introduced in the model are necessary and whether the influence of each module on the existence of the model is conducive to model detection. In this study, YOLOv7 served as the benchmark model. Various modules were integrated into a custom strawberry dataset to evaluate its performance. Four YOLOv7 variants were compared: YOLOv7, YOLOv7+ShuffleNetv2, YOLOv7+ShuffleNetv2+Slim-neck, and YOLOv7+ShuffleNetv2+Slim-neck+CARAFE.

As shown in Table 3, after replacing the YOLOv7 backbone network with ShuffleNetv2, the number of parameters decreased by 46.2 % and FLOPs(G) decreased by 62.1 %. After adding the lightweight neck structure Slim-neck, the accuracy remained unchanged and the number of parameters and FLOPs(G) decreased by 7.5 % and 34.1 %, respectively. After the introduction of the upsampling operator CARAFE, the number of parameters and FLOPs (G) decreased by 37.8 % and 23.6 %, respectively, while FPS improved by 4.71 %. Compared to YOLOv7, the YOLOv7-SSC model reduces parameters and FLOPs by 69.0 % and 81.0 %, respectively, achieves an mAP@0.5 of 99.6 %, and maintains a high FPS of 90.91. Therefore, based on comprehensive analysis, the YOLOv7-SSC proposed in this paper may be a better detection model in this study.

Table 3Compare the performance of each module in YOLOv7-SSC

Index | FPS | Params(M) | FLOPs(G) | mAP(%) |

YOLOv7 | 78.7 | 37.2 | 105.1 | 99.6 |

YOLOv7+ShuffleNetv2 | 85.5 | 20.0 | 39.8 | 99.6 |

YOLOv7+ShuffleNetv2+Slim-neck | 86.2 | 18.5 | 26.2 | 99.6 |

YOLOv7+ShuffleNetv2+Slim-neck+CARAFE (YOLOv7-SSC) | 90.9 | 11.5 | 20.0 | 99.6 |

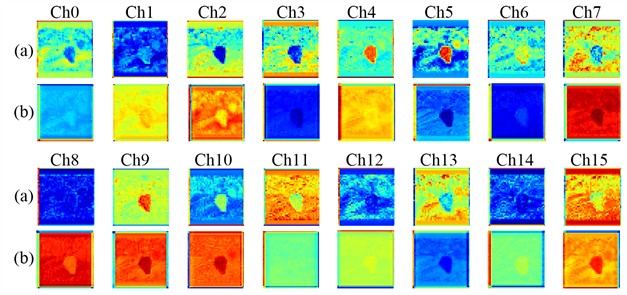

As visualized in Fig. 11, in the first 16 feature maps generated by CARAFE: (a) the input feature maps before upsampling show relatively blurred and scattered semantic information (such as strawberry edges and calyx regions); (b) the output feature maps after CARAFE processing demonstrate more concentrated, brighter activated regions representing small targets with clearer boundaries, while background noise is effectively suppressed. This significant improvement stems from CARAFE’s content-aware upsampling mechanism. By dynamically predicting location-specific kernels based on semantic context, CARAFE expands the receptive field and preserves fine-grained details-capabilities essential for distinguishing small, occluded strawberries from complex backgrounds. Consequently, this adaptive feature reconstruction allows the network to better perceive critical target information, leading to enhanced generalization and accuracy.

Fig. 11Feature map comparison before and after the CARAFE upsampling module: a) input feature maps before upsampling; b) output feature maps after upsampling (the first 16 channels)

5.4. Comparison performance of lightweight models

YOLOv7-SSC leads with 90.9 FPS, outperforming other models shown in Table 4. This high frame rate is critical for real-time applications such as guiding robotic harvesting arms. EfficientDet-Lite shows moderate speed, while YOLOv8-Nano lags significantly, likely due to its extreme lightweight design prioritizing parameter efficiency over parallel computation. In contrast, the RT-DETR model achieves the lowest FPS (35.82), which can be attributed to its more complex Transformer-based architecture and higher computational footprint, making it less suitable for high-speed real-time tasks despite its high accuracy.

YOLOv7-SSC has higher parameters but compensates with unmatched speed and accuracy, reflecting a balance tailored for GPU acceleration. YOLOv8-Nano is the most parameter-efficient model, making it suitable for deployment on ultra-low-power edge devices. EfficientDet-Lite strikes a middle ground but fails to leverage its moderate parameter count for competitive performance. RT-DETR, with the highest parameter count, embodies a non-lightweight design philosophy, prioritizing performance over efficiency.

YOLOv7-SSC incurs higher FLOPs due to its feature-rich architecture, which enhances precision and speed at the cost of computational demand. YOLOv8-Nano achieves the lowest FLOPs, ideal for energy-constrained environments. EfficientDet-Lite underperforms despite moderate FLOPs, indicating inefficient feature utilization. RT-DETR incurs the highest FLOPs by a significant margin, consistent with its large model size and complex structure, which results in superior accuracy but the slowest inference speed.

YOLOv7-SSC achieves the highest accuracy, demonstrating robustness in detecting small, occluded strawberries in cluttered field environments. RT-DETR matches this top accuracy at 99.6 %, validating the power of its advanced architecture, though at the expense of practical inference speed. YOLOv8-Nano follows closely at 99.5 %, validating its ability to retain precision despite extreme light weighting. EfficientDet-Lite lags significantly, rendering it impractical for precision-critical agricultural tasks.

YOLOv7-SSC is the top performer for applications requiring high speed and accuracy, such as automated harvesters or high-throughput sorting systems. Its higher FLOPs and parameters are justified by GPU-optimized efficiency and precision. YOLOv8-Nano excels in ultra-low-power edge deployment but sacrifices speed for extreme parameter efficiency. RT-DETR serves as an accuracy benchmark, demonstrating that even higher architectural complexity can yield marginal gains, but its low FPS and large size currently limit its practical deployment in real-time agricultural robotics. EfficientDet-Lite struggles to compete, offering neither the speed of YOLOv7-SSC nor the efficiency of YOLOv8-Nano, with poor accuracy.

5.5. Testing results of different detection models

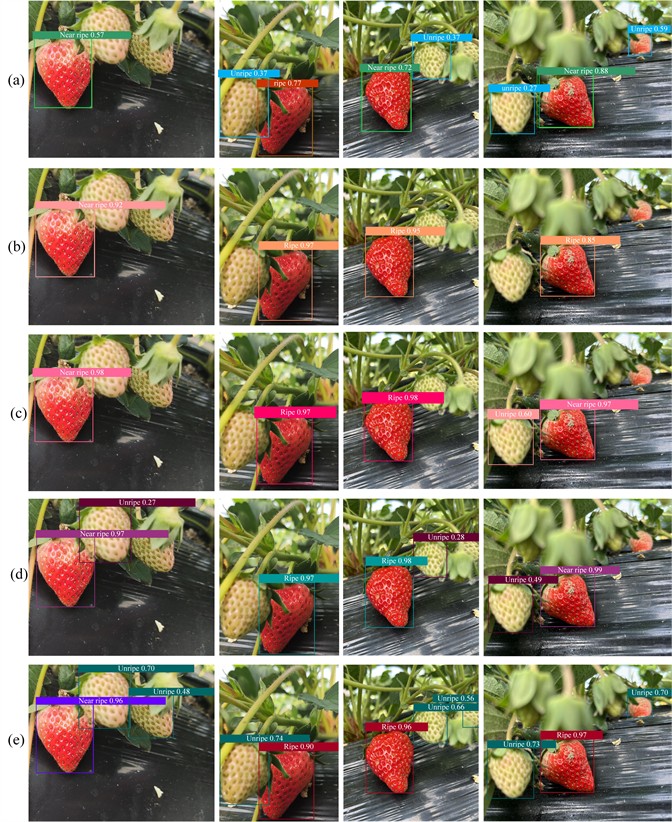

The obtained data sets were used to train and test different models to identify and detect strawberries in different growth states. Part of the test results are shown in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12Detection results of some representative strawberry images using different algorithm detections: a) EfficientDet-Lite; b) YOLOV8-Nano; c) RT-DETR; d) YOLOv7; e) YOLOV7-SSC. Original photos were taken in Xinhua Village, Huainan City, Anhui Province, China, from March 1 to March 10, 2023, by Yuanmeng Wang, Xinyi Chen, and Ruoqi Wu

Table 4Performance of lightweight models

Model | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | FPS | mAP (%) |

EfficientDet-Lite | 4.2 | 10.5 | 78.6 | 95.7 |

YOLOv8-Nano | 3.0 | 8.1 | 53.7 | 99.5 |

RT-DETR | 41.6 | 95.2 | 35.8 | 99.6 |

YOLOv7-SSC | 11.5 | 20.0 | 90.9 | 99.6 |

It can be seen (Fig. 12) from the test results of group (a) that the EfficientDet-Lite model accurately detects most strawberries with few false positives, albeit with lower confidence scores for classification. However, it failed to detect smaller, distant, or severely occluded fruits. These observations align with its lower mAP score presented in Table 4, highlighting the trade-off between lightweight design and detection performance in complex field environments. Moreover, ripe strawberries and near-ripe strawberries can be detected using YOLOV8-Nano model with high scores, as illustrated in group (b). However, the YOLOv8-Nano model exhibits a high rate of missed detections for strawberries that are occluded, small-scale, or have low contrast with the background, reflecting the performance ceiling inherent to its extreme lightweight design. As shown in the test results of group (c), RT-DETR demonstrates superior detection accuracy and localization quality. However, it exhibits missed detections for strawberries that are occluded, small in scale, or have colors similar to the background. Furthermore, its FPS is significantly lower than that of the YOLO family models. Consequently, RT-DETR offers no practical advantages for deployment in agricultural robotic systems. As the baseline model, YOLOv7 demonstrates powerful detection capabilities. Nevertheless, it exhibits missed detections for smaller-sized strawberries or those with colors similar to the background shown in the detection results of group (d). Furthermore, its highest parameter count and computational complexity result in less competitive detection speed.

Compared with these lightweight models, the improved YOLOV7-SSC model can realize the high-precision detection of different growth states of strawberry targets shown in the test results of group (e), which further proves that the network proposed in this study has a good effect on improving the detection of strawberry maturity. Moreover, the YOLOv7-SSC model exhibits superior performance in accurately detecting small objects. Therefore, it is highly necessary to optimize the recognition model based on the characteristics of the detection targets to improve target detection accuracy.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes YOLOv7-SSC, a lightweight multi-target detection framework designed for dense strawberry orchards with significant occlusion and complex backgrounds. By integrating the ShuffleNetV2 backbone, Slim-neck with GSConv, and CARAFE upsampling modules, the model achieves an optimal balance between accuracy, speed, and field deployability in agricultural vision systems.

The experimental results show that compared with the original YOLOv7 model, parameters and FLOPs(G) of the improved model are reduced by 69.0 % and 81.0 %, respectively, mAP@0.5 is 99.6 % and the FPS is as high as 90.91. Compared with the detector of the same level, it can be seen that the proposed model YOLOv7-SSC in this paper achieves the most balanced performance across all indexes, and its lightweight network structure and efficient detection results are more suitable for the detection task of strawberries maturity. The improved framework can be extended to other crops and integrated with robotic arms for end-to-end automated harvesting, significantly reducing labor costs in precision agriculture. Future work will focus on multi-modal fusion for enhanced ripeness grading and ultra-low-power optimization for microcontroller deployment.

References

-

I. Pérez-Borrero, D. Marín-Santos, M. E. Gegúndez-Arias, and E. Cortés-Ancos, “A fast and accurate deep learning method for strawberry instance segmentation,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, Vol. 178, p. 105736, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105736

-

A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G. E. Hinton, “ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks,” Communications of the ACM, Vol. 60, No. 6, pp. 84–90, May 2017, https://doi.org/10.1145/3065386

-

K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman, “Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition,” in International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), pp. 1–14, 2015.

-

C. Szegedy et al., “Going deeper with convolutions,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 1–9, Jun. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2015.7298594

-

K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 770–778, Jun. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2016.90

-

P. M. Bhatt et al., “Image-based surface defect detection using deep learning: a review,” Journal of Computing and Information Science in Engineering, Vol. 21, No. 4, p. 04080, Aug. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4049535

-

G. Wen, Z. Gao, Q. Cai, Y. Wang, and S. Mei, “A novel method based on deep convolutional neural networks for wafer semiconductor surface defect inspection,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, Vol. 69, No. 12, pp. 9668–9680, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/tim.2020.3007292

-

R. Wang, C. F. Cheung, C. Wang, and M. N. Cheng, “Deep learning characterization of surface defects in the selective laser melting process,” Computers in Industry, Vol. 140, p. 103662, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2022.103662

-

X. Shen et al., “A multi-expert diffusion model for surface defect detection of valve cores in special control valve equipment systems,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 237, p. 113117, Aug. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2025.113117

-

X. Shen et al., “VLCIM: a vision-language cyclic interaction model for industrial defect detection,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, Vol. 74, pp. 1–13, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/tim.2025.3583364

-

Z. Ge, S. Liu, F. Wang, Z. Li, and J. Sun, “YOLOX: exceeding YOLO series in 2021,” arXiv:2107.08430, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2107.08430

-

A. Bochkovskiy, C.-Y. Wang, and H.-Y. M. Liao, “YOLOv4: optimal speed and accuracy of object detection,” arXiv:2004.10934, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2004.10934

-

J. Redmon and A. Farhadi, “YOLOv3: an incremental improvement,” arXiv:1804.02767, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1804.02767

-

Y. Fan, S. Zhang, K. Feng, K. Qian, Y. Wang, and S. Qin, “Strawberry maturity recognition algorithm combining dark channel enhancement and YOLOv5,” Sensors, Vol. 22, No. 2, p. 419, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22020419

-

S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick, and J. Sun, “Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, Vol. 39, No. 6, pp. 1137–1149, Jun. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031

-

H. Zhang, P. Lin, J. He, and Y. Chen, “Accurate strawberry plant detection system based on low-altitude remote sensing and deep learning technologies,” in 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ICAIBD), May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/icaibd49809.2020.9137479

-

D. Wang, X. Wang, Y. Chen, Y. Wu, and X. Zhang, “Strawberry ripeness classification method in facility environment based on red color ratio of fruit rind,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, Vol. 214, p. 108313, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2023.108313

-

W. Cho, M. Na, S. Kim, and W. Jeon, “Automatic prediction of brix and acidity in stages of ripeness of strawberries using image processing techniques,” in 34th International Technical Conference on Circuits/Systems, Computers and Communications (ITC-CSCC), pp. 1–4, Jun. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/itc-cscc.2019.8793349

-

S.-J. Kim, S. Jeong, H. Kim, S. Jeong, G.-Y. Yun, and K. Park, “Detecting ripeness of strawberry and coordinates of strawberry stalk using deep learning,” in 13th International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), pp. 454–458, Jul. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/icufn55119.2022.9829583

-

N. Lamb and M. C. Chuah, “A strawberry detection system using convolutional neural networks,” in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), pp. 2515–2520, Dec. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/bigdata.2018.8622466

-

R. Thakur, G. Suryawanshi, H. Patel, and J. Sangoi, “An innovative approach for fruit ripeness classification,” in 4th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), pp. 550–554, May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/iciccs48265.2020.9121045

-

C. Wang et al., “Real-time detection and instance segmentation of strawberry in unstructured environment,” Computers, Materials and Continua, Vol. 78, No. 1, pp. 1481–1501, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2023.046876

-

L. Cao, X. Zheng, and L. Fang, “The semantic segmentation of standing tree images based on the Yolo V7 deep learning algorithm,” Electronics, Vol. 12, No. 4, p. 929, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12040929

-

K. Zhao, L. Zhao, Y. Zhao, and H. Deng, “Study on lightweight model of maize seedling object detection based on YOLOv7,” Applied Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 13, p. 7731, Jun. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/app13137731

-

C.-Y. Wang, A. Bochkovskiy, and H.-Y. M. Liao, “YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors,” in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 7464–7475, Jun. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr52729.2023.00721

-

J. Terven, D.-M. Córdova-Esparza, and J.-A. Romero-González, “A comprehensive review of YOLO architectures in computer vision: from YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS,” Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 1680–1716, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/make5040083

-

S. Wang, C. Xia, F. Lv, and Y. Shi, “RT-DETRv3: real-time end-to-end object detection with hierarchical dense positive supervision,” in 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), pp. 1628–1636, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1109/wacv61041.2025.00166

-

S. Xu, X. Wang, and W. Lv, “PP-YOLOE: An evolved version of YOLO,” arXiv:2203.16250, 2022.

-

X. Qi, R. Chai, and Y. Gao, “Algorithm of reconstructed SPPCSPC and optimized downsampling for small object detection,” (in Chinese), Computer Engineering and Applications, Vol. 59, No. 20, pp. 158–166, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3778/j.issn.1002-8331.2305-0004

-

S. Liu, L. Qi, H. Qin, J. Shi, and J. Jia, “Path aggregation network for instance segmentation,” in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 8759–8768, Jun. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2018.00913

-

X. Ding, X. Zhang, N. Ma, J. Han, G. Ding, and J. Sun, “RepVGG: making VGG-style ConvNets great again,” in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 13728–13737, Jun. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01352

-

N. Ma, X. Zhang, H.-T. Zheng, and J. Sun, “ShuffleNet V2: practical guidelines for efficient CNN architecture design,” in Computer Vision – ECCV 2018, pp. 122–138, Oct. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01264-9_8

-

J. Feng, C. Yu, X. Shi, Z. Zheng, L. Yang, and Y. Hu, “Research on winter jujube object detection based on optimized Yolov5s,” Agronomy, Vol. 13, No. 3, p. 810, Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030810

-

H. Li, J. Li, H. Wei, Z. Liu, Z. Zhan, and Q. Ren, “Slim-neck by GSConv: a lightweight-design for real-time detector architectures,” Journal of Real-Time Image Processing, Vol. 21, No. 3, p. 62, Mar. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11554-024-01436-6

-

J. Wang, K. Chen, R. Xu, Z. Liu, C. C. Loy, and D. Lin, “CARAFE: content-aware reassembly of features,” in 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 3007–3016, Oct. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/iccv.2019.00310

-

J. Li, Z. Zhu, H. Liu, Y. Su, and L. Deng, “Strawberry R-CNN: recognition and counting model of strawberry based on improved faster R-CNN,” Ecological Informatics, Vol. 77, p. 102210, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102210

-

A. Howard et al., “Searching for MobileNetV3,” in IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 1314–1324, Oct. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/iccv.2019.00140

-

K. Han, Y. Wang, Q. Tian, J. Guo, C. Xu, and C. Xu, “GhostNet: more features from cheap operations,” in IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 1577–1586, Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00165

About this article

This work was supported by the Huainan City Science and Technology Plan Project (No. 2023A3112), Anhui University-level Special Project of Anhui University of Science and Technology (No. XCZX2021-01), Open Fund of Mechanical Industry Key Laboratory of Intelligent Mining and Beneficiation Equipment (No. 2022KLMI03), Open Research Grant of Joint National-Local Engineering Research Centre for Safe and Precise Coal Mining (No. EC2023015), Scientific Research Foundation for High-level Talents of Anhui University of Science and Technology (No. 2022yjrc18), Jiangsu Planned Projects for Postdoctoral Research Funds (No. 2018K165C), and Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2208085ME128).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Renyuan Wu: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration and writing-review and editing. Xinyi Chen: data curation and methodology. Yuanmeng Wang: data curation, methodology and writing-original draft preparation. Ruoqi Wu: data curation and writing-review. Shuangli Wang: investigation, resources and writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.