Abstract

Accurate attitude tracking of six degree of freedom electrohydraulic shaking tables (EHSTs) is restricted by parameter uncertainty, nonlinearity, strong coupling, and external disturbances. Existing sliding mode control schemes are limited by fixed switching gains and the absence of integral compensation, which restrict steady-state accuracy and dynamic adaptability under nonlinear hydraulic effects and multi-axis coupling. An Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control (AISMC) scheme is developed to address these factors through two coordinated elements: an integral sliding surface that removes steady state deviation caused by static disturbances such as servo valve dead zones and hydraulic leakage, and an adaptive switching gain that regulates the reaching dynamics online without reliance on conservative bounds; a decay term in the gain update restrains parameter drift and keeps the adaptation bounded. Lyapunov analysis establishes closed loop stability and finite time convergence of the tracking error under bounded uncertainties and excitations. Simulation studies on a six degree of freedom EHST with a broadband random reference (0.1-10 Hz, 10 mm) compare AISMC with Sliding Mode Control (SMC) along , , and . Pose tracking shows consistent gains, with the maximum value reduced by about 11.5-11.9 % and the root mean square (RMS) reduced by about 34.9-35.1 %. Pose error decreases from 0.392-0.396 mm to 0.035-0.036 mm in maximum value and from 0.175-0.177 mm to 0.015-0.016 mm in RMS. Acceleration tracking under AISMC approaches the reference in and and improves in , while acceleration error decreases by about 83.5 % in and and about 88 % in . The results indicate higher control precision, smoother transients with reduced chattering, and robust multi axis coordination suitable for practical vibration testing applications.

Highlights

- An adaptive integral sliding mode control (AISMC) scheme is developed, integrating an integral sliding surface with an online adaptive switching gain to eliminate steady-state errors and suppress chattering.

- The proposed AISMC achieves superior multi-axis tracking precision, reducing pose error by an order of magnitude and acceleration error by over 83% compared to conventional SMC under broadband random excitation.

- Lyapunov stability analysis guarantees finite-time convergence of the tracking error, demonstrating robust performance against parameter uncertainties, nonlinearities, and strong coupling in 6-DOF electro-hydraulic systems.

1. Introduction

The EHST is a core platform for simulating vibration environments of large-scale structures and serves an essential function in structural testing and reliability evaluation [1]. EHSTs reproduce a wide range of acceleration inputs, such as sinusoidal, sine-sweep, Gaussian random, non-Gaussian random, and response-spectrum signals so that laboratory excitation better reflects service conditions. In practice, tracking accuracy is limited by nonlinearities, parameter uncertainty, time-varying dynamics, fluid compressibility, friction, servo-valve dead zones, and external disturbances in the electro-hydraulic servo loop [2-5]. A variety of tracking controllers have been reported for EHSTs, including PID variants, model-based feedforward, robust and sliding-mode designs, and adaptive schemes. Yet under broadband, high-amplitude, and high-frequency excitation, many designs face a trade-off between chattering suppression, disturbance rejection, and steady-state accuracy. Addressing this limit, the present work develops an Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode (ISM) framework for attitude tracking on 6-DOF EHSTs that targets concurrent improvement in robustness, precision, and stability.

For single-tone sinusoidal vibration tests, amplitude attenuation is the principal metric for assessing reproduction accuracy. In multi-sinusoidal and multi-shaker applications, both amplitude attenuation and phase delay must be treated as core indicators, since interchannel phase coordination governs spatial coherence and load fidelity [6, 7]. Many laboratories also track harmonic distortion and coherence to ensure consistency between the command waveform and the table response across time and frequency. To improve response fidelity, Wani et al. [8] proposed a response-based adaptive strategy termed Interstory Displacement-based Response Adaptive (IDRA) control. The controller updates parameters by minimising interstory displacement responses, and experiments together with numerical studies confirmed its effectiveness. These results indicate that online adaptation driven by measured responses can reduce tracking error under varying structural states and excitation levels. Addressing dynamic coupling, Zhao et al. [9] developed modal-space three-state feedback plus feedforward strategy for a two-degree-of-freedom electro-hydraulic table. Based on detailed kinematic and dynamic models, the method suppresses coupling introduced by eccentric loads and improves tracking under complex payloads and off-centre mass distributions. In nonlinear compensation, Helian et al. [10] presented an adaptive nonlinear pump-flow compensation approach for direct-drive hydraulic systems. The design targets low-speed pump characteristics and inherent loop nonlinearities and thus improves motion accuracy, highlighting the importance of adaptive robustness in electro-hydraulic control. For precise waveform generation, Yang et al. [11] combined adaptive control with inverse-model compensation and sliding-mode design to realise continuous swept-frequency sinusoidal vibration and achieved accurate trajectories over a wide frequency range. A related study by Yang et al. [12] reported a practical adaptive sinusoidal controller tailored to EHSTs that maintains accurate motion under changing vibration conditions, which is essential for realistic seismic simulation and qualification testing. These studies advance response adaptation, coupling suppression, and nonlinear compensation for EHSTs and point to the need for integrated strategies that regulate amplitude and phase over broad frequency bands while maintaining robustness under payload-dependent coupling and actuator constraints.

Model Predictive Control (MPC) combined with Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) design and Linear Parameter Varying (LPV) modelling has been investigated for electro-hydraulic applications. Rodriguez-Guevara et al. [13] introduced an MPC LQR LPV controller with quadratic stability conditions for active vehicle suspensions driven by electro-hydraulic actuators, showing that a unified model-based framework can handle nonlinear dynamics and constraints with high fidelity. Beyond control laws, flow management has been explored to raise actuation bandwidth and damping. Lu et al. [14] proposed a dual-valve drive with reduced flow to improve the dynamic performance of electro-hydraulic servo drives. Simulation and experimental studies reported higher response speed and improved closed-loop stability when the valve configuration shapes the flow profile. In related work, Chen et al. [15] developed an integrated trajectory-planning and motion-control strategy based on a variable-speed pump. A full-state constraint formulation imposes motion and pressure limits during trajectory generation and tracking, which yields precise path following and stable pressure regulation under practical constraints. Above mentioned literature points to two main directions for high-performance electro-hydraulic drives: predictive control that fuses LQR and LPV modelling within MPC with stability guarantees, and hydraulic architecture co-design of valves and pumps with control to meet strict tracking and constraint requirements.

Yong et al. [16] examined an inverse-model control approach based on signal filtering and Backpropagation (BP) neural networks for Electric Servo Cylinders (ESCs). Nonlinear behaviour in ESCs degrades vibration reproduction accuracy; inverse control compensates by pre-shaping the input so that the plant output tracks the target response. Adaptive refinement further improves fidelity, as shown in [17], where an enhanced feedforward inverse control with adaptive refinement improves acceleration tracking. Hydraulic hardware remains a determining factor for amplitude and frequency regulation. As noted in [18], servo valves are central to precise modulation of pressure and flow in electro-hydraulic drives. Advancing this line, [19] reports three-stage servo valves that raise control fidelity and response speed. Multi-stage amplification allows fine metering of hydraulic pressure and flow, which directly shapes the vibration characteristics of the shaking table. Careful design and optimisation of valve dynamics, leakage paths, and spool geometry are essential for stable and accurate seismic simulation, particularly in bi-axial and multi-directional configurations where bandwidth, phase alignment, and cross-axis coupling impose stricter requirements.

Shaking table control research has progressed along both algorithmic and hardware-aware lines, aiming at high-fidelity vibration reproduction under nonlinear, time-varying, and disturbance-rich conditions. Within this context, Zhang [20] proposed a modified three-variable controller for a hydraulic adaptive bearing system to optimise load response, paired with a multi-state observer strategy that suppresses vibration and improves ride comfort. Regarding nonlinear behaviour in EHSTs, Liang et al. [21] documented friction effects and nonlinear hydraulic responses that degrade tracking accuracy. To cope with parameter variations and unmodelled dynamics, adaptive robust control based on Extended State Observers (ESOs) has gained traction. Wen et al. [22] presented an ESO-based adaptive robust scheme that estimates lumped disturbances online and compensates them within the loop, which strengthens robustness against uncertainties and external inputs.

Further advances target precision waveform regulation and modal decoupling in complex plants. Ramírez [23] applied an LMS adaptive algorithm for harmonic suppression through real-time inversion of the hydraulic transfer path, reducing harmonic content and improving overall control performance. For mechanisms with eccentric loads, Wang [24] developed modal-space three-state feedback plus feedforward method for electro-hydraulic planar redundant drives, achieving improved dynamic response, stability, and disturbance rejection via explicit coupling treatment. For transient waveform replication, Tang et al. [25] proposed a composite approach that combines offline Iterative Learning Control (ILC) with improved Internal Model Control (IMC). The learning stage refines the feedforward profile across repetitions, while the IMC structure enforces model-consistent tracking, yielding higher fidelity in transient reproduction on shaking tables.

In system hardware, double layer shaking tables provide support for large displacement and high load testing. Pan et al. [26] reported the design and control of a large displacement double layer table that applies adaptive inverse control to replicate time waveforms with high precision, offering an effective platform for vibration evaluation of large-scale structures. Shen et al. [27] developed an improved feedforward inverse control scheme for Transient Waveform Replication on EHSTs that combines inverse transfer function compensation with simple Internal Model Control and a real time feedback loop, which raises fidelity for short duration events. Yao [28] integrated a nonlinear neural network with continuous robust integration of correct using error signs to compensate unknown state dependent disturbances, thereby stabilising response under variable operating conditions. Zheng et al. [29] proposed an adaptive algorithm for active control of parameter varying vibration systems; auxiliary filters refine online estimation of the secondary path and support stable adaptation during wideband excitation. Furthermore, the coupling of parameter identification with control laws has proven vital for system robustness. Liu and Ding [30] developed an iterative estimation algorithm utilizing Newton search for bilinear stochastic systems, demonstrating that accurate parameter updating significantly improves control fidelity under system uncertainties. Regarding specific actuator nonlinearities, Wang and Wang [31] proposed a fixed-time adaptive optimal parameter estimation strategy subject to dead-zones, which is highly relevant to compensating for the static limits inherent in servo valves.

Nonlinear effects in EHSTs can distort response, especially under sinusoidal acceleration input [32]. To improve acceleration tracking, Offline Iterative Control is widely adopted. Tian et al. [33] connected Offline Iterative Control in series with PID or Time Varying Control to refine the reference through repeated offline iterations, which reduces steady error and improves phase alignment over a broad frequency range. Adaptive control also plays an important role for EHSTs, with the Least Mean Square algorithm frequently applied. Practical deployments often pair the Least Mean Square algorithm with an offline inverse model [34], which yields rapid convergence and dependable real time performance under plant uncertainty [35]. Ma [36] presented a control method for multi axis sinusoidal frequency sweeping in random vibration tests, targeting coordinated amplitude and phase across channels. Dossogne [37] introduced a procedure to locate, characterise, and model nonlinear characteristics from sinusoidal swept frequency data, upgrading a linear numerical model to a validated nonlinear representation suitable for high fidelity simulation and controller synthesis.

SMC continues to receive strong attention in EHST regulation because it provides structured robustness to matched disturbances and model errors while retaining a clear design workflow from sliding surface selection to reachability and invariance analysis. Recent studies further extend this foundation with learning enhanced elements. For example, Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) networks have been embedded within robust controllers to adapt gains and capture slow parameter drift in hydraulic loops, which yields accurate attitude and acceleration tracking on EHSTs under varying operating conditions [38]. In parallel with specific algorithmic enhancements, broader control frameworks have been explored to bolster robustness. Zhu and Wang [39] investigated the incorporation of intelligent control with U-control (IU-control), providing a model-independent perspective that complements model-based robust designs in handling complex dynamic environments. In parallel, classical SMC in single input single output (SISO) settings has been validated for shaking tables and can attenuate disturbance forces, reduce steady error, and maintain stable operation across typical excitation bands [40,41]. Methodological breadth now spans hybrid testing and multi axis coordination. Yao [40] reported real time hybrid testing on shaking tables based on SMC, emphasising its utility in coping with the nonlinear behaviour of actuators and the presence of unexpected external inputs. For multi degree-of-freedom platforms, Zhang et al. [42] proposed a chatter free sliding mode strategy for a non contact six degree-of-freedom vibration system and demonstrated coordinated axis control without loss of precision. For complex multi-variable platforms, accurate configuration identification is a prerequisite for decoupling control. Ren et al. [43] presented an on-line configuration identification and control method for modular reconfigurable flight arrays, highlighting the necessity of real-time parameter identification in achieving high-precision coordination for multi-degree-of-freedom systems similar to 6-DOF shaking tables. Beyond deterministic trajectories, the literature documents SMC for reference tracking of random vibration models, where invariance on the sliding manifold improves simulation accuracy and stability under broadband excitation [1]. In aerospace oriented EHST applications, parameter adaptive sliding mode force control has been implemented and verified, indicating that SMC retains performance advantages under harsh environments that feature coupling, saturation, and tight stability margins [44]. Motivated by prior advances, the proposed controller adopts an improved SMC architecture that unifies adaptation and integral action to cancel steady-state error and retain robustness. The main contributions and distinctions of this work lie in the specific integration strategy and the robust adaptive mechanism tailored for electro-hydraulic systems. Unlike the classic integral sliding mode control which typically employs an auxiliary integrator to compensate for initial conditions, the proposed scheme embeds the integral action directly into the sliding manifold design. This structure is specifically tailored to eliminate the steady-state offsets caused by hydraulic-specific static nonlinearities, such as servo-valve dead zones and internal leakage, without increasing the order of the actuator dynamics. Furthermore, an adaptive switching gain with a leakage term is developed for the 6-DOF hydraulic coupling problem. While the mathematical form draws from classic robust adaptation approaches such as $\sigma$-modification, its application here is explicitly tuned to suppress the parameter drift induced by oil temperature variations and variable payload dynamics in shaking tables, ensuring bounded gain evolution where standard adaptation often diverges.

The outline of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents the servo control architecture of the EHST. Section 3 develops the adaptive integral sliding-mode controller and establishes stability via Lyapunov analysis. Section 4 formulates the composite adaptive integral sliding-mode strategy and reports simulation studies. Section 5 provides conclusions and outlines future research directions.

2. Servo control system: structure and function

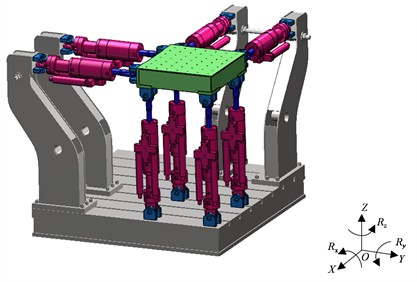

The six degree of freedom vibration table in Fig. 1 adopts a parallel platform layout that realises three translations along , , and directions, and three rotational degrees of freedom (, , and ). There are two vibrators each in the and directions (, , , ) generating planar motion and balance overturning moments Four vertical actuators in direction (, , , ) provide lift capacity and, through differential actuation, authority in pitch and roll. The arrangement improves load capacity and lateral stiffness while maintaining kinematic controllability for multi axis excitation.

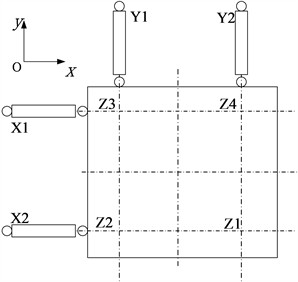

The structure of the traditional servo controller system is as shown in the Fig. 2. A three-state feedback loop based on position, velocity, and acceleration, together with a coordinated three-state feedforward path, improves closed-loop stability and widens the usable acceleration bandwidth. Degree-of-freedom (DOF) synthesis and decomposition matrices convert between platform-level commands and single-cylinder signals, securing phase alignment and balanced load sharing across actuators. A pressure stabilizer, typically realised with accumulators and an equalisation manifold, attenuates internal force coupling and cuts energy loss. Practical implementations also add compensation for valve and actuator dynamics, notch filters near structural resonances, anti-windup protection in the inner loops, and synchronisation across parallel actuators in , , and to maintain coherence at high frequency.

The control workflow proceeds as follows. The drive signal generator outputs a target acceleration profile, which passes through an integrator or shaping filter to form a displacement reference. A degree of freedom decomposition matrix maps the platform reference to single cylinder commands that actuate the vibration table. Sensors acquire cylinder states and table motion. A degree of freedom synthesis matrix aggregates single cylinder measurements into platform level responses, which are compared with the reference to produce the next control input, forming a closed loop. The three state structure uses displacement, velocity, and acceleration in both feedback and feedforward paths to shape dynamics and widen the useful acceleration band. During operation, a pressure sensor measures the differential pressure between the upper and lower chambers of each hydraulic actuator. A pressure stabilisation loop based on accumulators and an equalisation manifold reduces surplus internal forces and pressure ripple, lowers energy loss, and improves tracking accuracy and coordination across axes. The arrangement supports consistent phase among actuators and maintains stable motion under broadband excitation.

Fig. 1a) Description of the structural schematic of the 6-DOF electro-hydraulic vibration table; b) Description of the top view of the 6-DOF electro-hydraulic vibration table

a)

b)

2.1. Three-state control: design and method

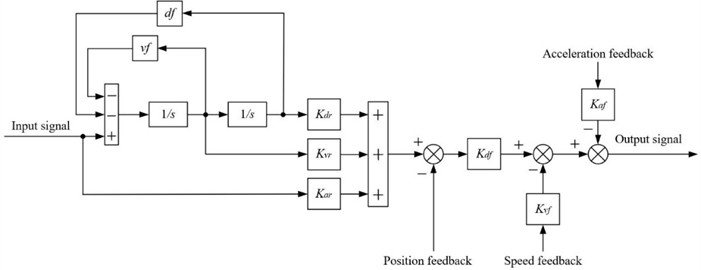

The three-state controller serves as the core component of the vibration table servo control system, in which the three states correspond to displacement, velocity, and acceleration of the table. The working principle of the three-state control is illustrated in Fig. 3. The controller is composed of two coordinated parts: a feedforward branch and a feedback branch.

Fig. 2Schematic of operating principle and controller structure

The three-state feedforward path is designed to compensate for the dynamic characteristics of the electro-hydraulic actuator by introducing weighted displacement, velocity, and acceleration terms. This feedforward mechanism effectively cancels the dominant poles located near the imaginary axis in the position closed-loop transfer function, thereby broadening the system’s acceleration frequency bandwidth and improving reference-tracking fidelity. The resulting compensation ensures that sinusoidal, swept-frequency, or random excitations can be accurately reproduced over a wide frequency range.

The three-state feedback loop provides additional damping and stiffness regulation to stabilise the hydraulic power mechanism. On the basis of a position closed-loop, velocity feedback increases the damping ratio, while acceleration feedback elevates the effective natural frequency, suppressing overshoot and enhancing disturbance rejection. Position, velocity, and acceleration feedback gains are tuned in combination to achieve a trade-off between responsiveness and stability. In practice, filters or observers are applied to process acceleration and velocity signals to reduce measurement noise. Through the integration of three-state feedforward and feedback control, the vibration table attains an expanded operating frequency range, improved dynamic stability, and higher precision in vibration reproduction.

Fig. 3Three-state controller structure

The open-loop transfer function of a typical electro-hydraulic position servo system can be expressed as:

where is the natural frequency of the servo valve (rad/s); is the Damping ratio of the servo valve(dimensionless); is the Flow gain of the servo valve (m³/s/A); is the Natural frequency of the power mechanism (rad/s); is the Damping ratio of the power mechanism, dimensionless; is the Effective area of the hydraulic cylinder (m²); is the Amplifier gain (A/V).

Ideally, after incorporating the three-state feedforward and feedback controllers, the desired closed-loop transfer function of the system is as follows:

where is the Desired system frequency bandwidth (rad/s); is the Natural frequency of the power mechanism (rad/s); is the Damping ratio of the power mechanism, dimensionless.

In terms of , then according to Eqs. (1-2) and Fig. 3, the calculation formulas for the feedback and feedforward coefficients of the three-state controller can be derived:

where denotes the three-state feedforward displacement gain; denotes the three-state feedforward velocity gain; denotes the three-state feedforward acceleration gain; denotes the three-state displacement feedback; denotes the three-state velocity feedback; denotes the three-state acceleration feedback.

The shaker acceleration is initiated at 0.5 Hz, 30 Hz, and the system damping ratio is set to 0.6. Based on these parameters, the feedback and feedforward coefficients of the three-state controller are determined using the derived design equations. With the controller design completed, the vibration table achieves stable operation, accurate response tracking, and reliable dynamic performance within the desired frequency range.

2.2. Degree of freedom control strategy for electro-hydraulic vibration tables

The use of a degree-of-freedom (DOF) independent control strategy enables flexible adjustment of the three-state control parameters and convenient configuration of reference signals for each motion component. The spatial distribution of the exciters in the vibration table system is shown in the Fig. 1. The distance between the upper hinge points of each pair of exciters is 0.64 m, and the spacing between adjacent exciters is also 0.64 m. Vertical motion along the -axis is achieved through the synchronous actuation of the four vertical exciters, while rotational motions about the and axes are generated through differential actuation between corresponding actuator pairs. Given that the platform adopts a square configuration, equal angular rotations about the axis require the same extension of the -direction actuators as that of the -direction actuators to maintain geometric consistency. This symmetrical layout simplifies stroke coordination, improves motion accuracy, and enhances load distribution among actuators. By decoupling control across each degree-of-freedom, this approach minimises cross-axis interference and supports precise 6-DOF motion reproduction under complex vibration excitation conditions.

The vibration table achieves six degrees of freedom, which can be expressed as:

Each term in Eq. (5) corresponds to the six DOFs of the platform, namely three translational motions and three rotational motions. From Eq. (5), the degree-of-freedom synthesis matrix is obtained, which maps single-cylinder responses into the platform DOFs :

From the matrix , it can be observed that when the vibration table operates under six-degree-of-freedom control, the solution for the eight actuator driving signals obtained from the above equation is not unique. The degree-of-freedom decomposition matrix can take multiple valid forms. The matrix has dimensions of 8×6 and, in practice, is defined as the least-squares pseudoinverse of the synthesis matrix , ensuring optimal mapping accuracy between actuator space and platform motion coordinates. In practice, selecting the least-squares pseudoinverse minimises actuator-space errors for a given pose demand, improving load sharing and reducing internal force amplification during coordinated motion:

2.3. Pressure stabilizer

The pressure stabilizer operates by taking the difference between the output force of each actuator and the average force of each degree-of-freedom as the feedback signal. Based on the feedback value, the zero position of each servo valve is adjusted to balance the hydraulic forces among the actuators and reduce internal force coupling within the system. Through continuous adjustment of the valve offset, the stabilizer minimises pressure fluctuation, decreases energy loss, and improves actuator coordination under combined loading conditions.

The output force of each exciter at a certain moment can be expressed as , where the magnitude of internal force coupling is . The average force of each degree-of-freedom can be obtained based on the position of each exciter:

As can be seen from the Eq. (8):

The internal force of each exciter is defined as the deviation between its actual output and the mean force associated with the corresponding degree-of-freedom, and it follows from the geometric relations of the system:

A control input is introduced to suppress internal forces. It drives each exciter’s output force towards the mean force associated with the relevant degree-of-freedom:

where, , (1, 2) and (1, 2, 3, 4) are the pressure gains of each exciter.

3. AISMC controller construction

In dynamic control of EHSTs, conventional SMC remains robust to parameter perturbations, yet practical operation is influenced by servo valve dead zones, nonlinear friction in hydraulic cylinders, temperature dependent variation of viscous damping, load changes, and ground vibration transmission. Under such disturbances, the fixed switching gain, the absence of an integral component, and the discontinuous switching characteristic constrain effectiveness in electrohydraulic applications and create bottlenecks in practice.

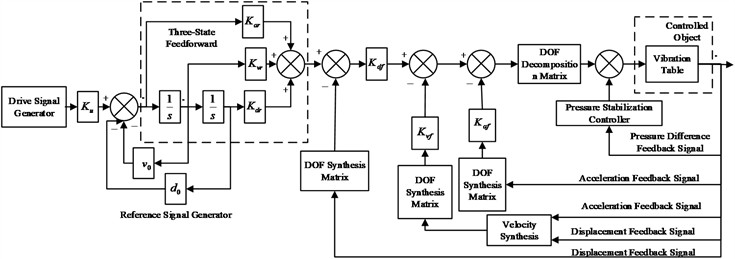

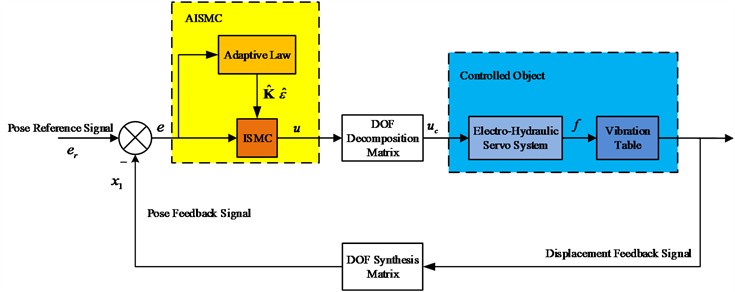

An AISMC scheme is therefore developed. The design integrates an integral sliding surface with an adaptive gain update law and delivers several advantages for EHST control. The integral sliding surface smooths the switching process of the control signal, while the adaptive mechanism adjusts the switching gain in real time. The combined effect reduces acceleration fluctuation, preserves vibration test signal fidelity, and prolongs the service life of hydraulic components. In addition, the adaptive law estimates nonlinear terms and unknown disturbances online and reconfigures the control gain to satisfy multiple operating conditions without manual retuning. The integral action embedded in the sliding surface removes steady state error that commonly arises in standard SMC. As shown in Fig. 4, the tracking controller in the diagram is constructed on the AISMC framework. The joint use of an integral sliding surface and online gain regulation suppresses low-frequency steady-state drift while maintaining rejection of high-frequency disturbances under time-varying hydraulic dynamics.

Fig. 4Vibration table control strategy based on AISMC

Firstly, during the initial input phase, the initial pose feedback signal is formed by synthesizing the initial displacement feedback signals (corresponding to the system's inherent initial state prior to control intervention) through the degree-of-freedom synthesis matrix. The pose error is then computed as the deviation between the pose reference signal and the synthesised pose feedback signal. The error is supplied to the AISMC module, where the adaptive law performs online adjustment of the switching gain in accordance with intrinsic system dynamics; the initial stage of the update naturally adapts to inherent characteristics. The adjusted gain together with the boundary layer acts on the integral sliding-mode component to generate the control signal . Thereafter, the control signal s decomposed by the degree-of-freedom decomposition matrix into multichannel inputs for the electrohydraulic servo system. Upon receiving , the electro-hydraulic servo system produces the driving force to actuate the vibration table, which executes the commanded motion and outputs displacement feedback signals. In subsequent control cycles, the displacement feedback signals generated by the vibration table’s motion are synthesized via the degree-of-freedom synthesis matrix to obtain an updated pose feedback signal, from which a new error is computed. The loop proceeds in a closed-loop process, delivering continuous adaptive regulation based on real-time responses.

3.1. AISMC design

The EHST system possesses inherent characteristics including parameter uncertainty, nonlinearity, strong coupling among channels, and sensitivity to external disturbances. Conventional SMC without an integral component is unable to eliminate steady state error, which limits control accuracy and fails to satisfy the stringent requirements of high precision vibration testing. In addition, sliding mode reaching laws with fixed parameters cannot adjust in real time to variations in system parameters or external perturbations, thereby constraining achievable control performance.

The displacement, velocity, and acceleration vectors of the vibration table system can be defined as the state variable :

Building upon the mathematical model presented in Section 2, the dynamic behaviour of the vibration can be expressed as follows:

where is the degree-of-freedom control signal, represents the set of uncertain parameters, and :

where is effective acting area of the hydraulic cylinder (m2); is viscous damping coefficient of the piston and load (N/(m/s)); is bulk modulus of elasticity of the fluid (Pa); is Total volume of the two chambers of the hydraulic cylinder (m3); is mass matrix; is total leakage coefficient, ((m3/s)/ Pa); is flow gain (m2/ s); is gain coefficient, (m/V).

The pose, velocity, and acceleration errors of the vibration table are defined to characterise the deviation between the reference motion signals and the calculated feedback responses, and can be expressed as follows:

where represents the reference pose.

In practical engineering, attitude control of electrohydraulic shakers encounters persistent static disturbances. Typical sources include servo valve dead zones and hydraulic cylinder leakage, both of which induce non-negligible steady state offsets in the closed loop response. To suppress such offsets and guarantee zero steady state error, an integral term is incorporated into the sliding surface so that the integral action drives the tracking error to zero during the steady state phase while preserving robustness to matched disturbances.

The sliding mode surface of the proposed controller is defined as follows:

where , , and are all positive-valued constant diagonal matrices.

This design is specifically targeting the inherent static nonlinearities of hydraulic systems (such as servo valve dead zones and leakage), aiming to eliminate steady-state error without auxiliary integrators at the actuator level. Differentiating Eq. (16) and combining the result with the state equation of the vibration table yields the following expression:

A typical exponential reaching law can be expressed as follows:

where, represents the exponential reaching term, and denotes the sign function. Since the coefficients and in the conventional reaching law are fixed constants without adaptive adjustment capability, the convergence performance cannot be optimised for different state variables. To mitigate control performance degradation and suppress chattering that may occur when large switching gains are applied to maintain system stability, adaptivity is introduced into the switching gain. The adaptive reaching law is defined as follows:

where both and are positive definite constant diagonal matrices: denotes the switching gain, and denotes the exponential convergence gain.

To maintain stability of the integral ISMC system, the switching gain must exceed the upper bound of the unknown system dynamics. In practice, specifying that bound in advance is extremely challenging. Consequently, adopting a large switching gain as a conservative strategy often degrades control performance and induces severe chattering, which compromises control accuracy and may even lead to faults in the electrohydraulic shaker. To resolve the issue, adaptivity is incorporated into the switching gain. Unlike fixed-gain SMC, where a conservative large gain is required to cover the worst-case scenario, the proposed adaptive law adjusts the gain online based on the system state. This mechanism minimizes chattering while maintaining robustness against uncertainties. An adaptive law for the switching gain is given as follows:

where is a positive constant with , represents the rate of change of the adaptive gain . is set to a very small positive value to ensure that remains positive. The boundary layer is denoted as , and its design takes into account the discrete control implemented on the actual vibration table. In this case, cannot be strictly equal to 0; instead, it is considered that the sliding surface is reached when .

When the system state deviates from the sliding surface, the switching gain increases rapidly, quickly driving the system state back to the sliding surface. Once the sliding surface is reached, the gain will decrease to alleviate the chattering problem. Subsequently, if becomes insufficient to counteract external disturbances, causing these disturbances to tend to pull the system away from the sliding surface, increases again to effectively counter these disturbances. Based on Eq. (17) and Eq. (19), the tracking control law of the system is given as follows:

Since the uncertain term of the system is unknown, the following control law can be used:

As shown in Eq. (22), the switching gain of the controller can be adaptively adjusted online in accordance with the system state variables. Under such a mechanism, the parameter in Eq. (22) can be further reduced, which contributes to the suppression of chattering within the system.

3.2. Stability analysis

To establish theoretical assurance of feasibility and robustness under parameter uncertainty, strong coupling, and external disturbances, stability of the AISMC scheme is analysed through the Lyapunov approach. The analysis concentrates on two key structural elements: the integration of an integral term within the sliding surface to eliminate steady-state offsets caused by static disturbances, and the introduction of an adaptive switching gain that varies online according to system dynamics. Such a design removes dependence on unknown upper bounds and avoids the excessive oscillations that typically arise under conservatively high switching gains. Based on this principle, a positive definite Lyapunov function is defined in Eq. (23). Differentiation yields Eq. (24), and subsequent substitution of the system dynamics and the control law leads to the inequality in Eq. (25), which forms the basis for stability proof:

Such a bound on the Lyapunov derivative ensures actuator synchronisation and prevents internal force amplification, which is critical for durable multi-axis operation. From the Eq. (25), is a positive constant. Since and hold constantly, it follows that guaranteeing bounded trajectories and finite-time reachability of the sliding manifold under Eq. (26). It can be observed that the derivative of the Lyapunov function remains non-positive under the prescribed parameter constraints, thereby ensuring bounded trajectories and guaranteeing finite-time reachability of the sliding surface. Under the control law defined in Eq. (26), the tracking error converges to zero within finite time, even in the presence of system uncertainties and external disturbances.

4. Simulation analysis

This section presents simulation-based verification of the proposed Adaptive Integral SMC strategy. For a comprehensive comparative analysis, the responses under conventional SMC, ASMC, ISMC, and the proposed AISMC are presented. This systematic comparison aims to isolate the contributions of the adaptive gain and the integral action respectively, and to demonstrate the superior performance of the composite AISMC strategy. The reference signal spans 0.1-10 Hz with a displacement amplitude of 10 mm and is applied to the shaking table model to examine tracking and robustness characteristics. Given the operational characteristics of the shaking table, simulations are conducted along the , , and directions to reflect multi-axis performance. The numerical settings, plant parameters, and controller coefficients used in the simulations are summarised in Table 1, providing a complete specification for reproducibility and interpretation of the results.

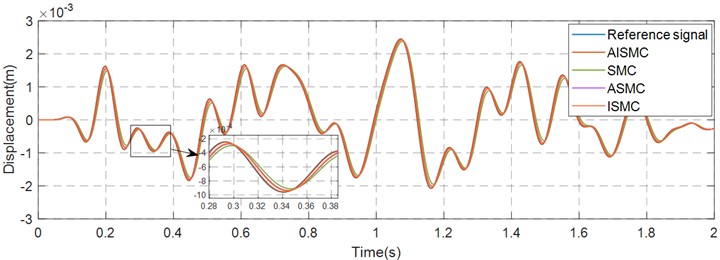

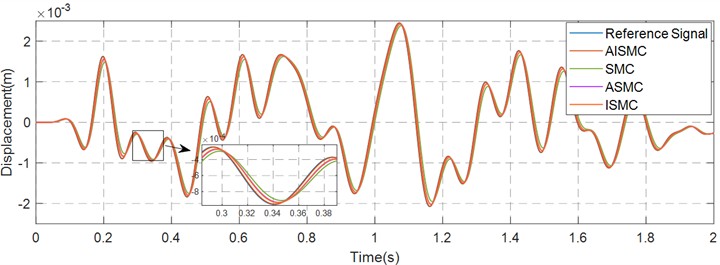

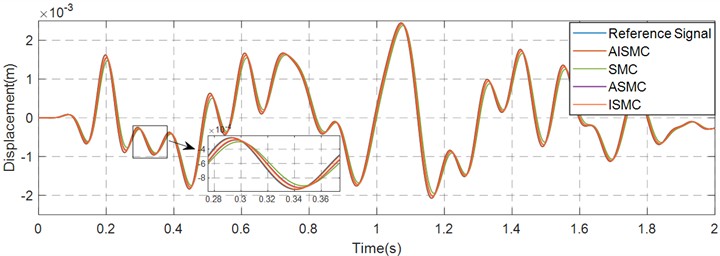

Pose tracking simulations are conducted with AISMC, ASMC, ISMC and SMC for a duration of 10 seconds. Figs. 5-7 show the tracking curves in the , , and directions over the interval 0 to 2 seconds, with enlarged insets highlighting 0.3 to 0.4 second for detail. The plots indicate that AISMC achieves superior tracking performance relative to SMC. Table 2 summarises pose statistics under the random reference input, reporting the maximum value and the root mean square (RMS) of pose in the , , and directions for the reference signal, conventional AISMC, ASMC, ISMC and SMC.

Table 1Simulation parameter settings

System parameters | Value | System parameters | Value |

Effective area of hydraulic cylinder | 0.0019 m2 | Damping ratio of servo valve | 0.6 |

Natural frequency of servo valve | 120 Hz | Flow rate of servo valve | 400 L/min |

Oil density | 845 kg/m3 | Supply oil pressure | 25 MPa |

Bulk modulus of oil | 700 MPa | Rated current of the servo valve | 10 mA |

Fig. 5Pose tracking curve in the X-direction

Fig. 6Pose tracking curve in the Y-direction

Fig. 7Pose tracking curve in the Z-direction

The quantitative results presented in Table 2 establish a clear performance hierarchy among the evaluated controllers. The conventional SMC exhibited the largest deviation with a root mean square value of 1.3548 mm in the direction. The introduction of adaptive mechanisms in ASMC and integral action in ISMC yielded moderate improvements, reducing the RMS values to approximately 0.938 mm and 0.940 mm respectively. These intermediate results indicate that introducing either adaptivity or integral action individually contributes to motion stability. However, the proposed AISMC strategy further suppressed the vibration energy, achieving an RMS value of 0.8794 mm. This represents an improvement of approximately 35.1 % over the conventional SMC and roughly 6.5 % over the ASMC and ISMC benchmarks, confirming that the combined strategy effectively minimizes vibration energy and achieves the smoothest motion profile.

Table 2Pose data under random signal simulation

Control Type | -direction | -direction | -direction | |||

The maximum value (mm) | RMS (mm) | The maximum value (mm) | RMS (mm) | The maximum value (mm) | RMS (mm) | |

Reference | 2.4498 | 0.8810 | 2.4498 | 0.8810 | 2.4498 | 0.8810 |

SMC | 2.7776 | 1.3548 | 2.7775 | 1.3548 | 2.7667 | 1.3513 |

ASMC | 2.4205 | 0.9383 | 2.4205 | 0.9384 | 2.4184 | 0.9375 |

ISMC | 2.4232 | 0.9404 | 2.4233 | 0.9404 | 2.4213 | 0.9396 |

AISMC | 2.4470 | 0. 8794 | 2.4470 | 0.8794 | 2.4470 | 0.8795 |

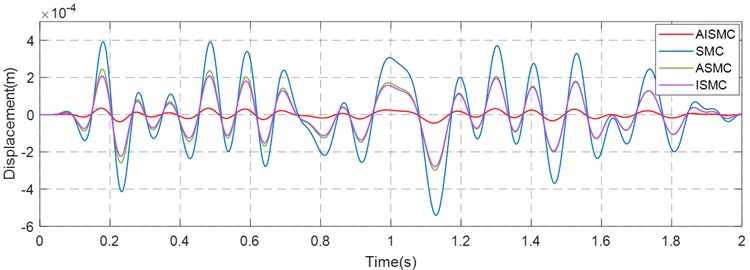

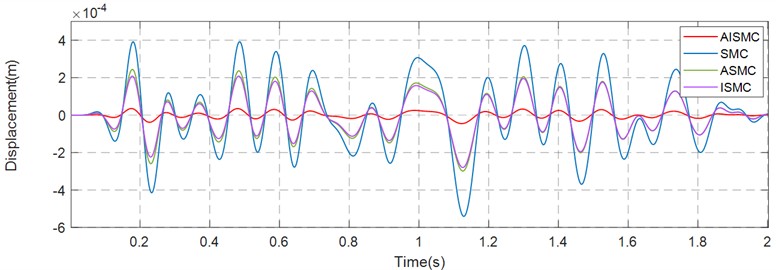

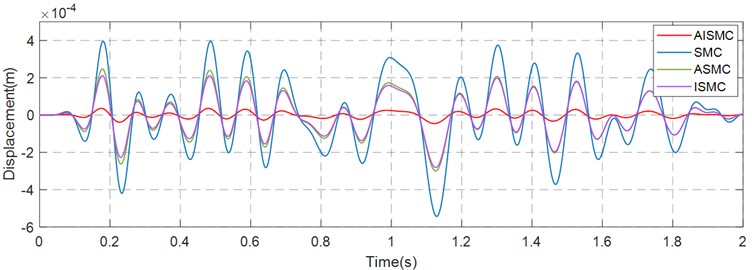

It summarises that AISMC significantly reduces fluctuation amplitude and peak deviation in the , , and directions, improving the precision and stability of pose control under random excitation. Figs. 8-10 show the error curves of S AISMC, ASMC, ISMC and SMC in the , , and directions, and the specific error values and RMS data are summarised in Table 3. The results demonstrate that AISMC achieves smaller steady-state and transient errors, ensuring more accurate tracking and smoother system performance.

Fig. 8Error curve in the X-direction

Fig. 9Error curve in the Y-direction

Fig. 10Error curve in the Z-direction

Table 3 highlights the critical advantage of the composite control architecture in terms of precision. Under the conventional SMC, the system suffered from significant tracking deviations, with a maximum error reaching 0.392 mm. While the maximum tracking errors under ASMC and ISMC were reduced to the range of 0.208 mm to 0.244 mm, representing a noticeable improvement over the SMC baseline, the AISMC approach demonstrated superior precision. By simultaneously compensating for static offsets and adapting to dynamic variations, AISMC minimized the maximum error to between 0.0351 mm and 0.0358 mm. Furthermore, the RMS error was reduced to the range of 0.0153 mm to 0.0156 mm. This constitutes a reduction of over 90 % compared to SMC and approximately 85 % compared to the ASMC and ISMC variants. These findings verify that the integration of integral action and adaptive laws creates a synergistic effect that is essential for eliminating steady-state deviations in high-precision applications.

Table 3Error data under random signal simulation

Control Type | -direction | -direction | -direction | |||

The maximum value (mm) | RMS (mm) | The maximum value (mm) | RMS (mm) | The maximum value (mm) | RMS (mm) | |

SMC | 0.392 | 0.175 | 0.393 | 0.176 | 0.396 | 0.177 |

ASMC | 0.2441 | 0.1083 | 0.2441 | 0.1083 | 0.2474 | 0.1094 |

ISMC | 0.2085 | 0.0997 | 0.2085 | 0.0997 | 0.2116 | 0.1008 |

AISMC | 0.0351 | 0.0153 | 0.0351 | 0.0154 | 0.0358 | 0.0156 |

The data indicate that, under SMC,ASMC, and ISMC, nonlinearity and coupling lead to pronounced lag and large peak deviations, with a worst-case maximum tracking error of 0.396 mm. After adopting AISMC, the maximum error decreases to 0.0351-0.0358 mm across axes, and RMS errors fall to about 0.015-0.016 mm. Such reductions reflect stronger suppression of peak excursions and broad band attenuation of error energy, resulting in high precision tracking of the random reference. The outcome aligns with integral action that eliminates steady state offsets and adaptive gain regulation that avoids conservative high gain operation and its associated chattering, thereby improving control accuracy and operational reliability of the electrohydraulic shaker.

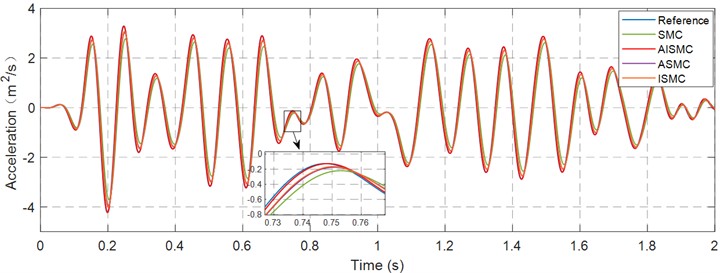

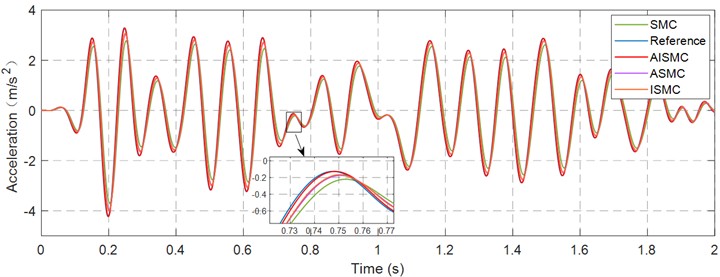

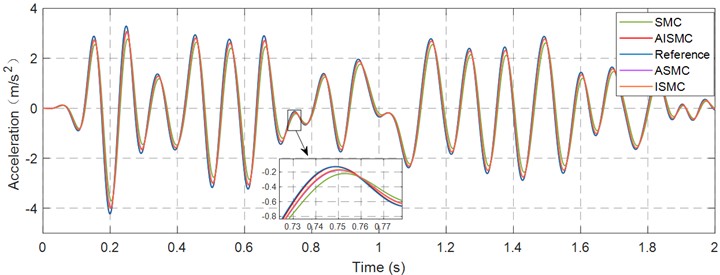

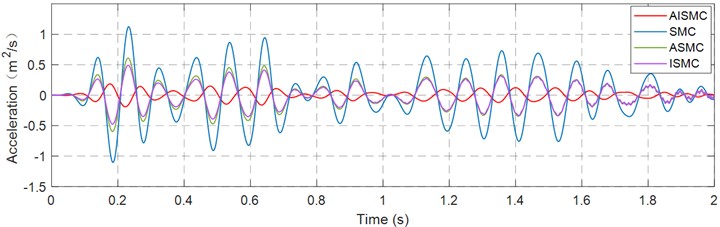

Figs. 11, 12, and 13 show the acceleration tracking results in the , , and directions under alternative control methods, thereby revealing the dynamic behaviour of the system under identical operating conditions. Table 4 provides a quantitative assessment of performance and summarises the principal statistical indices of acceleration, including peak and root mean square values, to facilitate direct comparison. The data indicate that the proposed control strategy achieves high precision tracking through online adjustment of the switching gain and effective suppression of fluctuation across axes, yielding stable and repeatable responses under the random reference input.

Fig. 11Acceleration tracking curve in the X-direction

Fig. 12Acceleration tracking curve in the Y-direction

Fig. 13Acceleration tracking curve in the Z-direction

Table 4Acceleration data under random signal simulation

Control type | -direction | -direction | -direction | |||

The maximum value (m/s2) | RMS (m/s2) | The maximum value (m/s2) | RMS (m/s2) | The maximum value (m/s2) | RMS (m/s2) | |

Reference | 3.2870 | 1.5282 | 3.2870 | 1.5282 | 3.2870 | 1.5282 |

SMC | 2.7776 | 1.3548 | 2.7775 | 1.3548 | 2.7667 | 1.3513 |

ASMC | 3.0311 | 1.4477 | 3.0311 | 1.4477 | 3.0313 | 1.4481 |

ISMC | 3.0734 | 1.4568 | 3.0733 | 1.4568 | 3.0771 | 1.4577 |

AISMC | 3.2873 | 1.5281 | 3.2933 | 1.5302 | 3.2907 | 1.5289 |

The capability of the controllers to reproduce high-frequency acceleration content is examined in Table 4. The reference signal demanded a peak acceleration of 3.287 m/s2. The conventional SMC failed to reach this target, saturating at approximately 2.77 m/s2 and resulting in significant amplitude attenuation. Although ASMC and ISMC partially recovered the dynamic response with peak accelerations reaching 3.03 m/s2 and 3.07 m/s2 respectively, they still exhibited distinct undershoot relative to the reference. In contrast, AISMC achieved a maximum acceleration of 3.29 m/s2 and an RMS value of 1.53 m/s2, figures that are virtually identical to the reference signal. This evidence suggests that the proposed controller effectively compensates for the low-pass characteristics and nonlinear damping of the hydraulic system, ensuring high-fidelity signal reproduction across the frequency band.

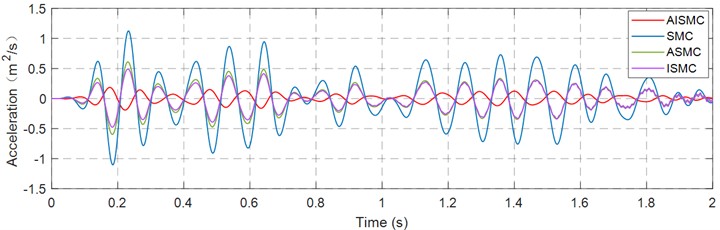

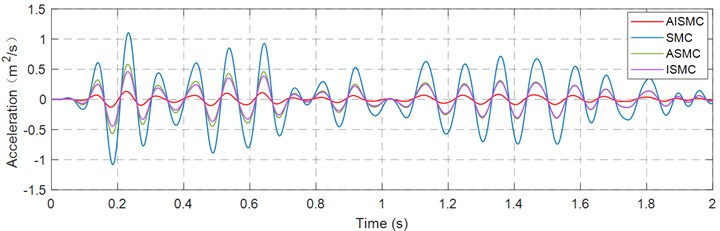

Figs. 14-16 present the acceleration tracking error in the , , and directions under SMC, ASMC, ISMC and AISMC, under identical operating conditions, allowing direct visual comparison of transient overshoot, steady state bias, and broadband fluctuation. Table 5 further quantifies performance and summarises the principal statistical indices of acceleration error, including maximum absolute error and RMS error. The data provide quantitative evidence that AISMC suppresses peak error and reduces RMS across all axes, reflecting higher fidelity in acceleration reproduction for vibration testing.

Fig. 14Acceleration error curve in the X-direction

Fig. 15Acceleration error curve in the Y-direction

Fig. 16Acceleration error curve in the Z-direction

The error statistics detailed in Table 5 further validate the robustness of the proposed scheme. The conventional SMC yielded a high RMS error of 0.418 m/s2, reflecting its limited capacity to handle rapid transient changes. The ASMC and ISMC methods reduced the RMS error to a range of 0.169 m/s2 to 0.209 m/s2, which constitutes a reduction of approximately 50 % compared to the SMC baseline. The AISMC framework outperformed all comparative benchmarks by lowering the RMS error to a range of 0.0477 m/s2 to 0.0688 m/s2. This corresponds to an improvement of roughly 83 % to 88 % over SMC and approximately 70 % over the separate ASMC and ISMC approaches. These results demonstrate that while adaptive gain handles parametric uncertainty and integral action addresses static bias, only the unified AISMC framework successfully suppresses both peak transients and broadband fluctuations to ensure high-fidelity waveform replication.

Table 5Acceleration error data under random signal simulation

Control Type | -direction | -direction | -direction | |||

The maximum value (m/s2) | RMS (m/s2) | The maximum value (m/s2) | RMS (m/s2) | The maximum value (m/s2) | RMS (m/s2) | |

SMC | 1.1246 | 0.4183 | 1.1246 | 0.4183 | 1.1049 | 0.4099 |

ASMC | 0.6097 | 0.2085 | 0.6097 | 0.2085 | 0.5821 | 0.1971 |

ISMC | 0.4908 | 0.1813 | 0.4908 | 0.1813 | 0.4612 | 0.1694 |

AISMC | 0.1855 | 0.0688 | 0.1856 | 0.0688 | 0.1318 | 0.0477 |

The comprehensive simulation analysis presented in this section confirms the superior performance of the AISMC strategy in maintaining accurate multi-axis tracking under complex, time-varying conditions. Comparative studies across the four control architectures reveal that while the ASMC and ISMC variants offer partial improvements over the conventional SMC baseline, they lack the combined efficacy required for high-precision vibration reproduction. The proposed AISMC framework integrates the benefits of online gain adaptation and integral compensation to achieve the tightest suppression of peak deviations and the most significant reduction in steady-state and transient errors. This synergistic approach effectively mitigates chattering without relying on conservative switching gains, thereby establishing a robust and reproducible baseline for subsequent experimental validation on full-scale electro-hydraulic platforms.

5. Conclusions

Attitude tracking for six degree-of freedom EHSTs is addressed with an AISMC scheme designed for uncertainty, nonlinearity, strong coupling, and external disturbances. The approach combines an integral sliding surface with an adaptive switching gain and is supported by Lyapunov analysis that establishes closed loop stability and finite time convergence under bounded uncertainties and excitations. Methodological advances are articulated in three mutually reinforcing components. First, integral action is embedded directly in the sliding surface from the initial instant, removing steady state deviation caused by static disturbances such as servo valve dead zones and hydraulic leakage, without auxiliary integration at the actuator level. Second, the switching gain varies online with the evolving state and disturbance magnitude, which avoids conservative fixed gains, mitigates chattering, and preserves robustness during both the reaching phase and motion on the sliding surface. Third, inclusion of a leakage term in the gain update restrains parameter drift and keeps the adaptive gain bounded under time varying operating conditions, supporting sustained multi axis coordination.

Comparative simulations with SMC on a six degree-of-freedom platform indicate uniform gains across , , and . Pose tracking exhibits smaller peak deviation and lower RMS levels, pose error is reduced by about one order of magnitude, and acceleration tracking aligns closely with the reference while the associated error drops markedly across axes. The combined outcome points to improved tracking precision, smoother transients with reduced chattering, and lower stress on hydraulic components during broadband random testing. AISMC therefore provides a practical route to high precision multi axis attitude control in vibration testing systems. Future work includes full-scale implementation with saturation and sensor-noise tests, incorporation of disturbance observers, and coordinated internal-force suppression via DOF synthesis and decomposition validated under broadband seismic profiles.

References

-

D.-M. Fan and G.-F. Guan, “Random vibration model reference sliding mode control of electro-hydraulic shaking table based on linear state observer,” in 7th International Conference on Automation, Control and Robotics Engineering (CACRE), pp. 172–177, Jul. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/cacre54574.2022.9834109

-

X. Yan, J. Yuan, H. Yu, A. Bobet, and Y. Yuan, “Multi-point shaking table test design for long tunnels under non-uniform seismic loading,” Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, Vol. 59, pp. 114–126, Oct. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2016.07.002

-

M. Jahed Orang, R. Motamed, A. Prabhakaran, and A. Elgamal, “Large-scale shake table tests on a shallow foundation in liquefiable soils,” Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, Vol. 147, No. 1, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0002427

-

M. F. Vassiliou et al., “Shake table testing of a rocking podium: Results of a blind prediction contest,” Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics, Vol. 50, No. 4, pp. 1043–1062, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.3386

-

H. Wang, Z. Chen, and J. Huang, “A novel method for high-frequency non-sinusoidal vibration waveforms with uniaxial electro-hydraulic shaking table based on Fourier series,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 27, No. 21-22, pp. 2466–2481, Sep. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546320961719

-

W. Xie, L. Sun, and M. Lou, “Shaking table test verification of traveling wave resonance in seismic response of pile-soil-cable-stayed bridge under non-uniform sine wave excitation,” Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, Vol. 134, p. 106151, Jul. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2020.106151

-

P. Verboven, P. Guillaume, S. Vanlanduit, and B. Cauberghe, “Assessment of nonlinear distortions in modal testing and analysis of vibrating automotive structures,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 293, No. 1-2, pp. 299–319, May 2006, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2005.09.039

-

Z. Rashid Wani, M. Tantray, and E. Noroozinejad Farsangi, “Shaking table tests and numerical investigations of a novel response-based adaptive control strategy for multi-story structures with magnetorheological dampers,” Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 44, p. 102685, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102685

-

J. Zhao, X. Sun, J. Xu, J. Dong, W. Li, and C. Zhang, “Modal space three-state feedback and feedforward control for 2-DOF electro-hydraulic servo shaking table with dynamic coupling caused by eccentric load,” Mechatronics, Vol. 79, p. 102661, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechatronics.2021.102661

-

B. Helian, Z. Chen, B. Yao, L. Lyu, and C. Li, “Accurate motion control of a direct-drive hydraulic system with an adaptive nonlinear pump flow compensation,” IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 2593–2603, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/tmech.2020.3043576

-

H. Yang, D. Cong, Z. Yang, and J. Han, “Continuous swept-sine vibration realization combining adaptive sliding mode control and inverse model compensation for electro-hydraulic shake table,” Journal of Vibration Engineering and Technologies, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 1007–1019, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-021-00425-4

-

H. Yang, D. Cong, Z. Yang, L. Zhang, and J. Han, “A practical adaptive sinusoidal vibration control strategy for electro-hydraulic shake table,” Journal of Vibration Engineering and Technologies, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 1725–1739, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-022-00667-w

-

D. Rodriguez-Guevara, A. Favela-Contreras, F. Beltran-Carbajal, C. Sotelo, and D. Sotelo, “An MPC-LQR-LPV controller with quadratic stability conditions for a nonlinear half-car active suspension system with electro-hydraulic actuators,” Machines, Vol. 10, No. 2, p. 137, Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/machines10020137

-

J. Lu, H. Xie, Y. Chen, and H. Yang, “Flow-reduced double valve actuation for improving the dynamic performance of electro-hydraulic servo drive,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, Vol. 237, No. 2, pp. 294–305, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062221121983

-

Z. Chen, B. Helian, Y. Zhou, and M. Geimer, “An integrated trajectory planning and motion control strategy of a variable rotational speed pump-controlled electro-hydraulic actuator,” IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 588–597, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/tmech.2022.3209873

-

Y. Sang, L. Guo, L. Liao, and L. Jiang, “An inverse model control method based on signal filtering and BP neural network to improve performance of electric servo cylinder system,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, Vol. 239, No. 22, pp. 9073–9087, Sep. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062251359409

-

Y. Tang, Z.-C. Zhu, G. Shen, and X. Li, “Improved feedforward inverse control with adaptive refinement for acceleration tracking of electro-hydraulic shake table,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 22, No. 19, pp. 3945–3964, Aug. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546314567725

-

C. Gao, J. Wang, X. Yuan, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, and M. Qin, “Review on the construction development and control technology of the shaking table,” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Smart Infrastructure and Construction, Vol. 174, No. 1, pp. 22–31, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1680/jsmic.21.00007

-

L. Zhang, D. Cong, Z. Yang, Y. Zhang, and J. Han, “Optimal design and hybrid control for the electro-hydraulic dual-shaking table system,” Applied Sciences, Vol. 6, No. 8, p. 220, Aug. 2016, https://doi.org/10.3390/app6080220

-

L. Zhang, Y. Liu, T. Yang, R. Wang, J. Feng, and D. Crosbee, “Modelling, analysis and validation of hydraulic self-adaptive bearings for elevated floating bridges,” Sensors, Vol. 24, No. 24, p. 8079, Dec. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24248079

-

J. Liang, Z. Ding, Q. Han, H. Wu, and J. Ji, “Online learning compensation control of an electro-hydraulic shaking table using Echo State Networks,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 123, p. 106274, Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106274

-

J. Wen, C. Zhao, Y. Wang, and Z. Shi, “Extended‐state‐observer‐based adaptive robust control of a single‐axis hydraulic shaking table,” IET Control Theory and Applications, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 442–453, Oct. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1049/cth2.12582

-

J. Ramírez-Senent, J. H. García-Palacios, and I. M. Díaz, “Shaking table control via real-time inversion of hydraulic servoactuator linear state-space model,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part I: Journal of Systems and Control Engineering, Vol. 235, No. 9, pp. 1650–1666, Apr. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1177/09596518211007294

-

J. Wang, A. Liu, X. Li, Z. Zhou, S. Chen, and J. Ji, “Effect assessment for the interaction between shaking table and eccentric load,” Scientific Reports, Vol. 12, No. 1, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19743-y

-

Y. Tang, G. Shen, Z.-C. Zhu, X. Li, and C.-F. Yang, “Time waveform replication for electro-hydraulic shaking table incorporating off-line iterative learning control and modified internal model control,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part I: Journal of Systems and Control Engineering, Vol. 228, No. 9, pp. 722–733, Jun. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1177/0959651814536553

-

P. Peng, G. Youming, K. Yingjie, W. Tao, and H. Qinghua, “Development of a double-layer shaking table for large-displacement high-frequency excitation,” Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Vibration, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 193–207, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11803-022-2080-9

-

G. Shen, G.-M. Lv, Z.-M. Ye, D.-C. Cong, and J.-W. Han, “Feed-forward inverse control for transient waveform replication on electro-hydraulic shaking table,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 18, No. 10, pp. 1474–1493, Oct. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546311417743

-

Z. Yao, J. Yao, F. Yao, Q. Xu, M. Xu, and W. Deng, “Model reference adaptive tracking control for hydraulic servo systems with nonlinear neural-networks,” ISA Transactions, Vol. 100, pp. 396–404, May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2019.11.027

-

H. Zheng, D. Yang, X. Xie, and Z. Zhang, “An adaptive algorithm for active vibration control of parameter-varying systems with a new online secondary path estimation method,” IEEE Signal Processing Letters, Vol. 27, pp. 705–709, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/lsp.2020.2986139

-

S. Liu and F. Ding, “Iterative Estimation Algorithm for Bilinear Stochastic Systems by Using the Newton Search,” ICCK Transactions on Intelligent Systematics, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 76–84, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.62762/tis.2024.155941

-

S. Wang and X. Wang, “Fixed-time adaptive optimal parameter estimation subject to dead-zone and control of servo systems,” ICCK Transactions on Sensing, Communication, and Control, Vol. 2, No. 3, p. 200, Aug. 2025, https://doi.org/10.62762/tscc.2025.143677

-

J. Yao, Y. Li, X. Yu, Y. Liu, S. Sun, and Y. Yan, “Acceleration harmonic identification for an electro-hydraulic shaking table based on the simulated annealing-particle swarm optimization algorithm,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 30, No. 1-2, pp. 193–204, Dec. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463221143409

-

Y. Tian, T. Wang, Y. Shi, Q. Han, and P. Pan, “Offline iterative control method using frequency-splitting to drive double-layer shaking tables,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 152, p. 107443, May 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2020.107443

-

G. Shen, X. Li, Z. Zhu, Y. Tang, W. Zhu, and S. Liu, “Acceleration tracking control combining adaptive control and off-line compensators for six-degree-of-freedom electro-hydraulic shaking tables,” ISA Transactions, Vol. 70, pp. 322–337, Sep. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2017.07.018

-

J. Yao, D. Di, G. Jiang, and S. Gao, “Acceleration amplitude-phase regulation for electro-hydraulic servo shaking table based on LMS adaptive filtering algorithm,” International Journal of Control, Vol. 85, No. 10, pp. 1581–1592, Oct. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207179.2012.694081

-

Y. Ma, H. Chen, and R. Zheng, “Control strategy for multi-axial swept sine on random mixed vibration testing,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 527, p. 116846, Jun. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2022.116846

-

T. Dossogne, L. Masset, B. Peeters, and J. P. Noël, “Nonlinear dynamic model upgrading and updating using sine-sweep vibration data,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, Vol. 475, No. 2229, p. 20190166, Sep. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2019.0166

-

J. Wen, C. Zhao, and Z. Shi, “LSTM‐based adaptive robust nonlinear controller design of a single‐axis hydraulic shaking table,” IET Control Theory and Applications, Vol. 17, No. 7, pp. 825–836, Dec. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1049/cth2.12410

-

Q. Zhu and H. Wang, “Primary thought on the incorporation of intelligent control and U-control (I-U-control),” ICCK Transactions on Sensing, Communication, and Control, Vol. 2, No. 3, p. 132, Jul. 2025, https://doi.org/10.62762/tscc.2025.880778

-

H. Yao, P. Tan, T. Y. Yang, and F. Zhou, “Shake table real-time hybrid testing for shear buildings based on sliding mode acceleration control method,” Structures, Vol. 52, pp. 230–240, Jun. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.03.140

-

G.-F. Guan and A. Plummer, “Acceleration decoupling control of 6 degrees of freedom electro-hydraulic shaking table,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 25, No. 21-22, pp. 2758–2768, Aug. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546319870620

-

Q. Zhang et al., “Backstepping sliding mode control strategy of non-contact 6-DOF Lorentz force platform,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 29, No. 5-6, pp. 1061–1075, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463211056763

-

B. Ren, J. Liu, S. Zhang, C. Yang, and J. Na, “On-line configuration identification and control of modular reconfigurable flight array,” ICCK Transactions on Intelligent Systematics, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 91–101, Sep. 2024, https://doi.org/10.62762/tis.2024.681878

-

J. Huang, Z. Song, J. Wu, H. Guo, C. Qiu, and Q. Tan, “Parameter adaptive sliding mode force control for aerospace electro-hydraulic load simulator,” Aerospace, Vol. 10, No. 2, p. 160, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace10020160

About this article

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52205064, 52105065), National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFC2809903), the Science and Technology Project of the Hebei Education Department (Grant No. QN2023035, CXZX2026065), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (Grant No. A2023210026), Hebei Province's Full-time Recruitment of High-level Talent Research Project (Grant No. 2024HBQZYCXY014), and the Major Technology Research and Development Programme of the Hebei Provincial Science and Technology (No. 24292201Z).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Yuan Liu: conceptualization, methodology, validation. Lianpeng Zhang: conceptualization. Ruichen Wang: methodology, formal analysis. Litong Lyu: validation. Jie Feng: data curation. Guangtao Ma: data curation.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.