Abstract

The reliability of modern building electrical systems are receiving increasing attention as they become more intelligent and complex. As the majority of building electrical systems use neutral point grounding, earth faults or short circuits can get worse over time and damage both the distribution system and the electrical equipment. To this end, the corresponding three phases and four categories, namely three-phase voltage, three-phase current after fault, three-phase voltage distortion rate, three-phase current distortion rate, a total of 12 dimensional fault feature vectors and 10 fault simulation types, were summarised and extracted in conjunction with the actual operating conditions of the system. Using traditional fault identification ideas and neural network algorithm as reference, a 12-dimensional fault feature vector is used as the model input to construct a building electrical fault diagnosis and detection model based on ELM algorithm. Results showed that the ELM-based model’s classification accuracy for this experimental sample was 97.56 %, its AUC was 0.92, and its RMSE was 0.3521. These figures were higher than the classification accuracy and performance of the BP algorithm and GA-BP algorithm fault diagnosis models, and they also demonstrate better robustness and generalizability. The model also has a 97.27 % correct rate in fault discrimination, while the computation time is only 0.201 s, and its fault identification and diagnosis speed is faster than other algorithmic models. At the same time, this research model has a good fault monitoring accuracy of up to 98.6 % for building electrical systems. The research can provide a more sensitive, accurate and rapid fault monitoring method for the current building electrical system. It also improves the reliability of the building electrical system in a complex environment and achieves better protection of the system. This has a certain significance for the development of the building electrical industry.

Highlights

- The proposed model based on ELM algorithm has a classification accuracy of 97.56%, detection performance of 0.92, and root mean square error of classification of 0.3521, all of which are higher than the fault diagnosis models of BP algorithm and GA-BP algorithm.

- The accuracy rate of the research model is 97.27%, the calculation time is only 0.2015s, and the fault identification and diagnosis speed is faster than other algorithm models.

- In addition, the fault monitoring accuracy of the research model is as high as 98.6%, showing better robustness and generalization.

- This research improves the reliability of building electrical system in complex environment and achieves better protection of the system.

1. Introduction

With the gradual evolution of modern building electrical systems towards complexity and intelligence, their operational status and reliability directly affect the normal operation of the system and are therefore of increasing concern [1]. Monitoring the condition of the system provides a prediction of how the system will operate when it is functioning properly. To determine the final results of fault diagnosis when the power system fails, the operation of power equipment and lines is tracked and studied [2]. At present, for the building electrical systems fault investigation automation degree is poor, mainly rely on manual monitoring, inspection and maintenance to carry out. In addition to wasting a lot of human resources, this occasionally necessitates taking a subsystem offline for inspection throughout the inspection process, which prolongs the time it takes for defects to be fixed. Another significant factor is that an electrical fire is more likely to start if this system fails [3-4]. It is therefore essential to improve the reliability of the building electrical systems under complex conditions, to find the best means of fault diagnosis and to maximize the normal operation of the system and the personal safety of the staff. Back Propagation (BP) neural networks are typical multi-layer feed-forward neural networks with good learning generalization capability and are widely used in today's predictive diagnostics and other systems [5]. Genetic algorithm optimization of BP is to optimize weights and connection thresholds of BP neural network, which can effectively improve the convergence speed and accuracy of the final result of BP network [6]. However, these two more mature fault diagnosis methods also have certain shortcomings, and many scholars are researching new algorithms with faster training speed and stronger generalization capability. Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) has faster training speed, strong pan-Chinese ability and global optimal solution searching ability. The main difference between ELM and BP networks is that the BP algorithm sets a fixed number of hidden layer neurons and relies on iteration to update the weight and threshold to achieve convergence. The ELM algorithm does not fix the number of hidden layer neurons and randomly inputs the threshold and weight. The algorithm can only obtain the unique optimal solution by changing the number of hidden layer neurons.

Therefore, to improve the safety of building electrical systems and improve its fault diagnosis efficiency, the research focuses on the safe operation of building electrical systems. On the basis of developing more mature neural network fault diagnosis technology, the fault causes and class diagnosis methods of building electrical power system are analyzed. A new system fault diagnosis model based on extreme learning machine (ELM) is proposed, which combines the advantages of other algorithms. The aim of this research is to provide a more sensitive, accurate and rapid fault monitoring method for the current building electrical systems, so as to achieve better protection of the system. The research mainly includes five parts, as follows:

1) Introduction. In the first part of this paper, the paper expounds the building electrical systems, and introduces the necessity and problems of the current building electrical systems fault diagnosis, as well as the relevant solutions.

2) Literature review. The content of the second part is a summary of fault diagnosis of building electrical systems, which mainly introduces the previous research results. This paper summarizes and analyses the design difficulties and methods of building electrical systems fault diagnosis.

3) Research methods. The research methods are mainly divided into two sections. In Section 2.1, the fault simulation method and feature extraction of building electrical systems are proposed. In Section 2.2, a fault diagnosis and monitoring construction method of building electrical systems based on ELM algorithm is designed.

4) Analysis of experimental results. The fourth part is the validity verification of the research model.

2. Related work

Intelligent fault diagnostic methods are currently drawing more attention from experts and academics both domestically and internationally as a crucial tool for data-driven control and application methods. Alcaiz et al. [7] proposed a collaborative approach for fault detection of residential PV systems that relies on PV systems. The study showed that the method has a strong ability to distinguish between system and actual fault problems. In order to address issues like the lack of historical fault data for wind turbines, Liu et al. [8] suggested a condition monitoring and fault isolation system, and the system's efficacy was confirmed through simulation. Pang et al. [9] used the method of infrared thermal imaging to detect the fault of electrical systems. The method was shown to detect fault and trend analysis effectively. Yang et al. [10] used a Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) to analyze faults in machine tools and experiments showed that the method was effective and better able to identify different types of faults. Shi et al. [11] applied an improved BP algorithm to diagnosis of aircraft fuel failure systems. Simulation results indicated the algorithm is fast in diagnosis and has a high prediction accuracy. To improve the performance of motor system fault diagnosis, researchers such as Zhang P. proposed a diagnosis method which combines chaotic adaptive gravity search algorithm and particle swarm optimization algorithm. The research results showed that the classification performance and diagnostic accuracy of the algorithm were improved after the introduction of adaptive gravitational constant attenuation factor and chaotic mapping [12]. Han Y. et al. proposed a method based on short-term wavelet entropy and support vector machine (SVM) to diagnose the inductance failures of the bridge arm of Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC). This studies revealed that this method was accurate and robust [13].

Kai et al. [14] applied a self-diagnosis method for sensor faults in building structural monitoring systems based on an optimized communication technology. Experiments showed that the method was able to quickly identify sensor faults and fault channels in the detection system. In order to solve the challenge of monitoring, evaluating, and diagnosing industrial gas turbine defects using conventional approaches, Elashmawi et al. [15] suggested a semi-artificial and intelligent ANN model to foretell the decline in a turbine engine's performance efficiency. The outcomes showed that, in comparison to the training data set, the model made predictions with a higher degree of accuracy. Sharma et al. [16] used a Support Vector Machine (SVM) based feature selection technique and an artificial neural network classification method for the automatic identification of engine faults. The artificial neural network was shown to have better performance than the SVM. Talaat et al. [17] used an artificial neural network to predict the deterioration of major engine components and selected the best neural network structure based on the minimum value of the MSE. The method was shown to be effective with high prediction accuracy. Xing et al. [18] introduced Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) for earthquake damage prediction and validated it against algorithms such as BP neural network and SVM. The results showed that the ELM-based algorithm gave the best prediction results.

The above research has shown that the current research on fault diagnosis methods is relatively solid and detailed, but there are still some unsolved and unrealistic problems. One is that the large number of sensors and false and missed alarms place a certain burden on the fault diagnosis process. Secondly, while the effectiveness of a single fault diagnosis approach is affected by the increasing complexity of fault diagnosis problems, the combination of several sophisticated diagnostic techniques does not guarantee that it will significantly increase the accuracy of system fault identification. The study combines the actual problem and based on the more mature fault diagnosis techniques of previous authors, the ELM algorithm is proposed to be used for the fault diagnosis about building electrical systems. The corresponding model is constructed by combining the advantages of neural network systems.

3. Research on the application of fault diagnosis techniques and monitoring methods in building electrical systems

3.1. Fault simulation methods for building electrical systems and their feature quantity extraction

Fault diagnosis is actually the determination and identification of whether the system is operating abnormally. There are many different types of faults in building electrical systems and each fault is accompanied by abnormal data. Fault diagnostics instantly classifies and identifies the collected data and determines the indications and types of faults. However, any fault diagnosis method must be based on a basic modelling and data collection of the building electrical system and fault conditions. The study therefore starts with an analysis of the modelling of the building electrical system, fault simulation and extraction of characteristics.

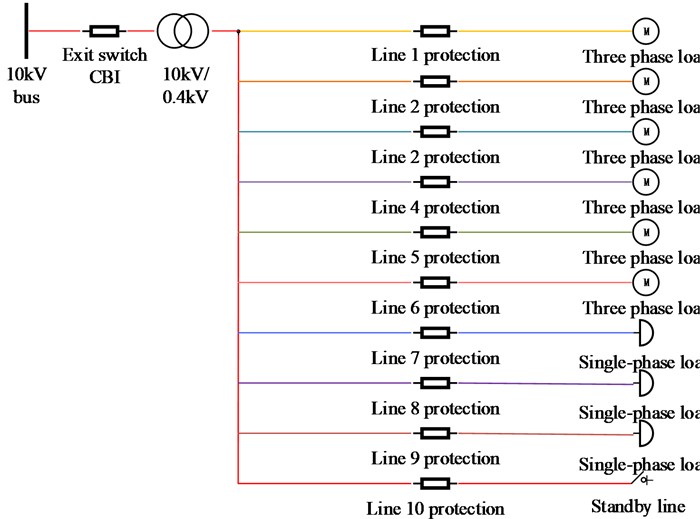

When modelling building electrical systems, they need to be constructed according to their characteristics, as they are located in different environments, have different requirements and vary greatly in their functionality. In this study, the MATLAB/Simulink library is used to build a model of the electrical distribution system by selecting the appropriate model components and parameters [19]. Fig. 1 shows, for example, an extracted line topology of a lighting outlet in a hospital distribution system.

Fig. 1Building electrical system topology

As can be seen from Fig. 1, the 10 kV busbar is the main network distribution line and CB1 is the distribution branch line switch. The main network current arrives at the distribution transformer via the branch line, which acts as a link between the low and high voltage sides and is used to step down the voltage from the high voltage side at 10 kV to the low voltage side at 0.4 kV. The building electrical system is modelled with a total of ten 0.4 kV outgoing lines, including six three-phase load fan coil lines and three single-phase load lighting-socket lines, as well as a standby line. To facilitate fault identification, a protection recording device was configured on each of these lines. The device is a three-phase voltage-current recorder, where the three-phase current and voltage values flowing through. Considering the economic constraints of the building electrical system, its sampling frequency is 20 kHZ. considering that the 10 kV system is generally a neutral point ungrounded system, set as the way the three phase voltage source is grounded.

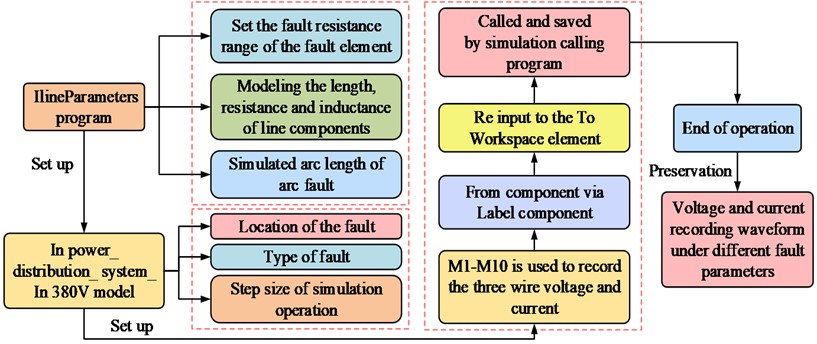

The parameter settings of the Powergui simulation master control element are related to the accuracy, effectiveness and time of the simulation. The study set the simulation method to discrete and the simulation time granularity to 5×10-5 s. Single-phase fault elements were selected to implement different fault types. In the specific simulation process, the study uses the program loop call method to improve the efficiency with the flexibility of modelling and easy modification [20]. In this case, the fault parameters are set in the fault element as variables to be retrieved from the workspace. In the study, the resistance was set to FR for resistive faults and the arc length was set to LC for arc faults. All components were aggregated and connected according to the topology of the building electrical system topology diagram in it [21]. The steps required to model the building electrical system during the simulation run are shown in Fig. 2.

As shown in Fig. 2, the simulation process was mainly carried out to obtain the recorded voltage and current waveforms for different fault parameters. After summarizing the fault transient voltages and currents obtained from the simulation and their characteristics, the study proposes several characteristic quantities for fault identification in building electrical systems. Firstly, the three-phase voltage scaling capabilities reflect the information about the voltage change before and after the fault, and also the magnitude of the change. Therefore, the minimum value of the three-phase voltage is one of the most characteristic quantities for fault diagnosis in building electrical systems, which is calculated as in Eq. (1) [22]:

where, represents the nominal value of the A-phase voltage after the fault, represents the magnitude of the A-phase voltage after the fault and is the magnitude of the A-phase voltage before the fault. The three phase currents are calculated as in Eq. (2) [23]:

where, represents the post-fault A-phase voltage scale value, represents the post-fault A-phase voltage magnitude and represents the pre-fault A-phase voltage magnitude. The difference in the voltage expression of the arcing fault can then be highlighted by calculating the distortion of the three-phase voltage after the fault; the calculation is illustrated in Eq. (3) [24]:

where, represents the three-phase voltage distortion rate, to represent the 2nd to harmonic voltage rms values and represents the fundamental voltage rms values. The distortion rate of three-phase current after fault is then calculated as shown in Eq. (4) [25]:

where, represents the three-phase current distortion rate, to represent the 2nd to harmonic current rms, and represents the fundamental current rms. The above four indicators are used as the characteristic vectors for the types of orphaned airplane plunges in the building electrical system. After obtaining the waveforms of various obstacle recordings, the four indicators are then calculated for the three-phase voltage and current of each fault to obtain 12 fault diagnosis characteristic vectors.

Fig. 2Steps of building electrical system modeling in simulation operation

The fault characteristic quantity data obtained by studying the simulation and extraction of low-voltage building electrical systems include three-phase voltage after fault, three-phase current after fault, the distortion rate of three-phase voltage and three-phase current in 12 dimensions, and the types of simulated faults include 10 categories. Table 1 shows these types and numbers of building electrical fault diagnosis and monitoring simulation faults for this study.

Table 1Classification of simulation fault data

Category No. | Fault type | Number of groups |

0 | Normal operation | 50 |

1 | Single phase grounding | 50 |

2 | Two phase short circuit | 50 |

3 | Two phase short circuit grounding | 50 |

4 | Three phase short circuit | 50 |

5 | Single phase arc grounding | 50 |

6 | Two phase arc short circuit | 50 |

7 | Three phase disconnection | 20 |

8 | Single-phase phase failure | 20 |

9 | Overload fault | 20 |

3.2. Building electrical system fault diagnosis and monitoring construction based on ELM algorithm

After the basic simulation of the type and number of faults and the extraction of the characteristic quantities for the building electrical systems and fault states, the appropriate algorithm must be used to model them, and then the model must be used for fault identification and diagnosis. BP neural networks are widely used in current fault diagnosis due to their multi-hidden layer structure, which increases the computational power of diagnosis [26]. However, BP neural networks also have some obvious drawbacks, resulting in slow convergence of the computational results, or not easy convergence. The ELM method is based on the BP algorithm. The benefits of the ELM are based on its network structure and mathematical principles, which don't fix the number of neurons in the hidden layer but instead generate connection weights and thresholds at random between the input and hidden layers before continuously changing the number of neurons in the hidden layer to produce a theoretically distinct optimal solution [27]. First, the connection weights between the input and hidden layers are set according to Eq. (5):

where, stands for connection weights between neuron of input layer and the neuron of the hidden layer. Similarly, the connection weights between implicit and output layer are shown in Eq. (6):

where, is the connection weights between neuron of the input layer and neuron of the hidden layer. Set threshold of neuron transmission to the hidden layer be , then its expression is shown in Eq. (7):

Set the data matrix of the training set with the number of samples be , then its expression is shown in Eq. (8):

Similarly, the output matrix is shown in Eq. (9):

When activation function is used for the neurons in hidden layer, let it be , then the network output is calculated as shown in Eq. (10):

where, is calculated as in Eq. (11):

In Eq. (12):

The above Eq. (12) can be simplified to Eq. (13):

where, represents the transposed form of matrix and is output matrix of hidden layer of the ELM network, which is expressed as shown in Eq. (14)[28-29]:

Two important theorems have been proposed in the context of the underlying neural network structure. The first is that for a single-hidden-layer Feedforward Neural Network (SLFN) with neurons, when faced with any different samples, where and for an infinitely differentiable activation function R over a wide interval [30]. For randomly assigned weights and thresholds , the output matrix is necessarily invertible for the hidden layer and has . Second, when faced with any number of different samples , where and . For any small error in a given environment, with an infinitely differentiable activation function R in any interval, there must exist an implicit layer SLFN containing a single neuron, with for randomly assigned weights and thresholds [31].

The ELM Extreme Learning Machine can be used in a stepwise manner when computing classification problems. The first step is to initialize the network with an input set of and an output set of . The output of the implicit layer is computed, and the connection weights and thresholds are computed through its input feature vector to obtain and the output of the implicit layer, which is expressed in Eq. (15):

For the output layer, the ELM neural network output value is calculated after accounting for the King City based on its structure by combining , the connection weights and the threshold . The calculation is shown in Eq. (16):

Eq. (17) illustrates how ELN may approximate the training sample with 0 error performance for any weight and threshold when activation function is an endlessly differentiable function if the number of neurons in the hidden layer is equal to the input in the actual problem:

It can be demonstrated that the error of the model derived from its training is incredibly small and is theoretically approximating the minimal value , as shown in Eq. (18), when the number of neurons in the hidden layer benefits the number of inputs in the actual problem. At this point, the number of input sets appears to be too large:

The frontal network weights of the output and hidden layers are then updated. ELM keeps its network connection weights in a previously constant state during model training, but needs to update the weights of the output and hidden layers, as shown in Eq. (19):

where, is Moore Penrose generalized inverse matrix [32] of the implied layer output matrix . The final step is to perform the iterative computation of this algorithm, as shown in Fig. 3.

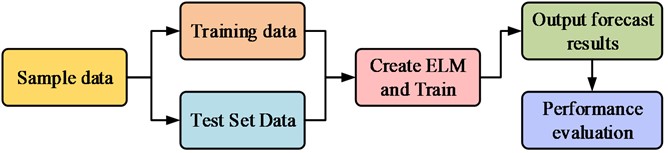

Fig. 3Steps to establish ELM extreme learning machine

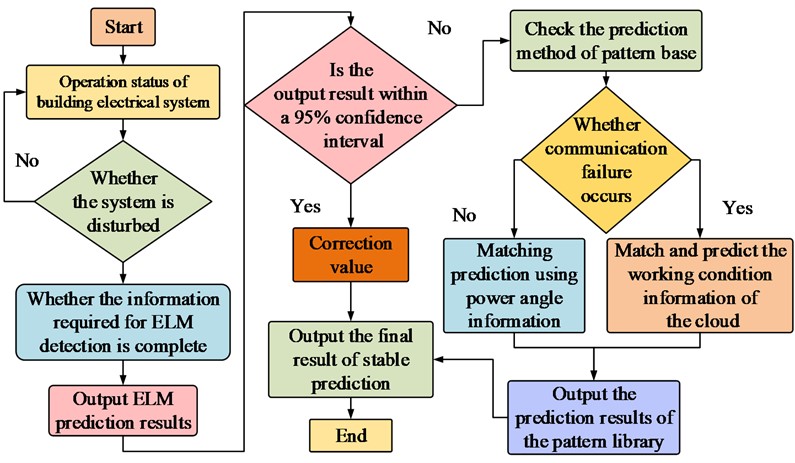

As seen in Fig. 3, the ELM is trained once a test set is produced. The ELM model is then tested by repeatedly iterating over the target accuracy values until the desired metric is obtained, resulting in the output of a performance evaluation of the ELM. If the set metric is not reached, the iterative computation continues. The study carried out model construction based on the above ELM algorithm principles, and structure of this model is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4Fault identification and monitoring model of building electrical system based on ELM algorithm

As shown in Fig. 4, the study uses the ELM algorithm to monitor and identify faults in building electrical systems. Being a fault diagnosis model, the model has many inputs and a single output. At this point, the input to the model is a 12-dimensional feature vector. Experimental analysis of fault diagnosis technology and monitoring method for building electrical system based on ELM algorithm.

4. Analysis of experimental results

4.1. Transient analysis of building electrical system fault simulation

Since the number of hidden layer neurons of ELM extreme learning machine cannot be determined, the algorithm is needed to search automatically. The specific parameter Settings of ELM extreme learning machine, BP neural network and GA-BP neural network are shown in Table 2.

Table 2Three kinds of neural network parameter Settings

Algorithm | ELM | Mapping function | Input layer | Tansig |

Activation function | Sigmoid | Hide Layers | Tansig | |

Weight threshold | ELM automatically finds the optimal solution | Output layer | Purelin | |

Number of hidden layer nodes | 13 | Training function | Training function trainlm of Levenberg Marquardt | |

Algorithm | BP | Mapping function | Input layer | Tansig |

Activation function | Sigmoid | Hide Layers | Tansig | |

Weight threshold | Random initialization, then gradient descent optimization to reduce the error | Output layer | Purelin | |

Number of hidden layer nodes | 13 | Training function | Levenberg Marquardt's BP algorithm training function trainlm | |

Algorithm | GA-BP | Mapping function | Input layer | Tansig |

Activation function | Sigmoid | Hide Layers | Tansig | |

Weight threshold | GA algorithm is initialized, and then gradient descent optimization is used to reduce the error | Output layer | Purelin | |

Number of hidden layer nodes | 13 | Training function | Levenberg Marquardt's BP algorithm training function trainlm |

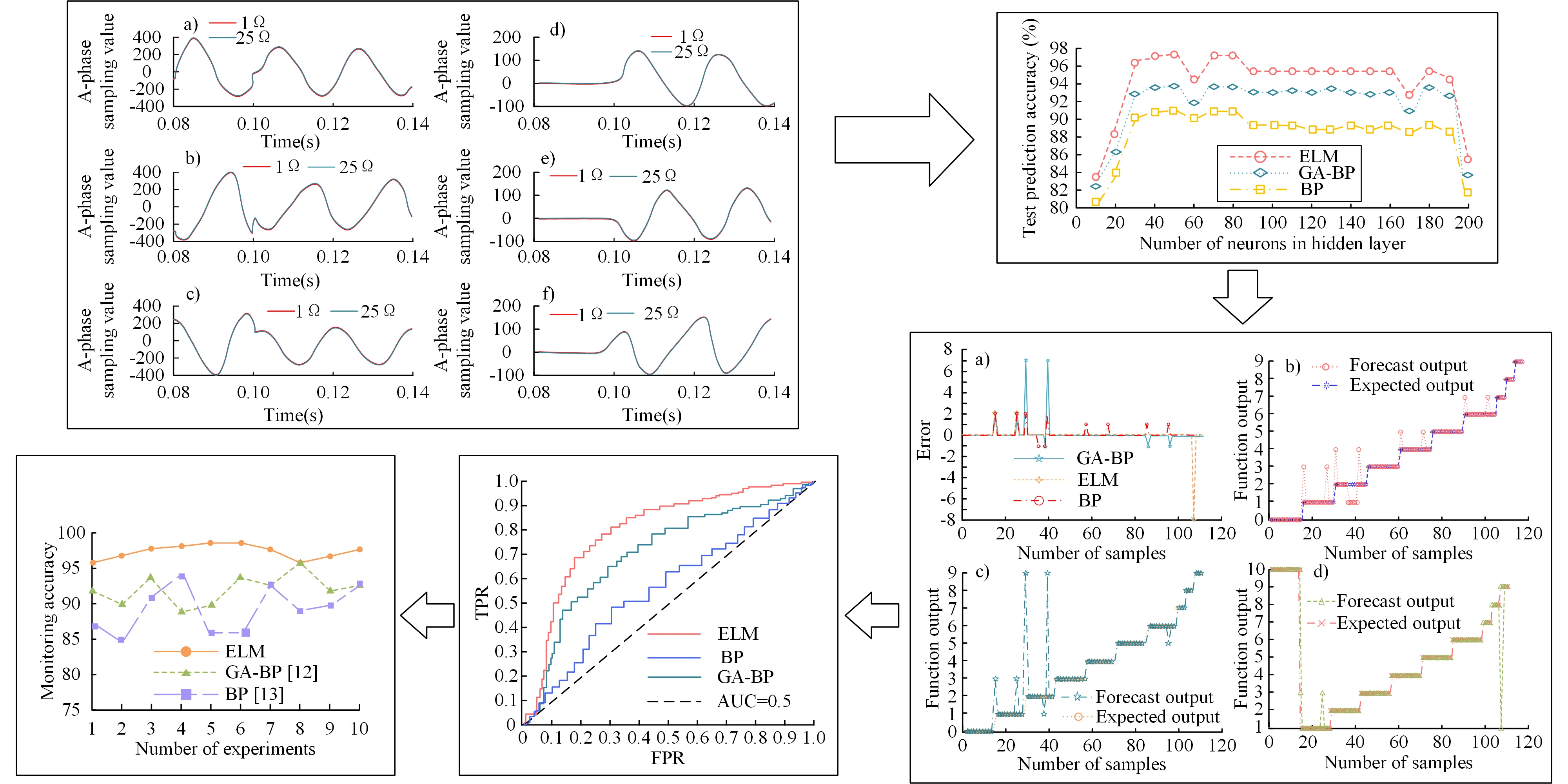

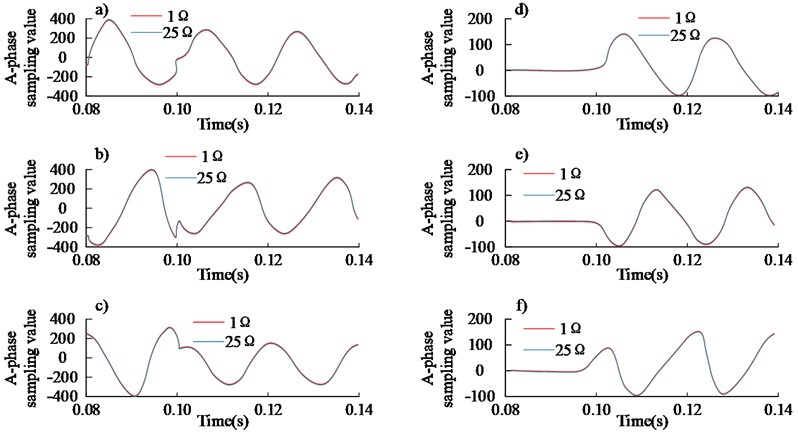

Fault simulations were performed on the modelled building electrical system, with the faults set to occur in the middle section of the line. For each type of fault in the model, several different sets of fault parameters were set to investigate the degree of change in system voltage and current and the trend under different fault parameters. This was done in an effort to simulate as closely as possible the faults that would occur in the field operation of the building electrical system. The wiring of the building electrical system was set up for an ABC three-phase short circuit fault. The fault resistance was varied from 1 Ω to 50 Ω, with a total of 50 sets of simulations. To highlight the contrast effect, only the transient voltage and current waveforms for the 1 Ω and 25 Ω simulations are drawn, as shown in Fig. 5. Note: Fig. 5(a) shows the A phase short-circuit fault simulation transient voltage. Fig. 5(b) shows the B phase short-circuit fault simulation transient voltage. Fig. 5(c) shows the C phase short-circuit fault simulation transient voltage. Fig. 5(d) shows the A phase short-circuit fault simulation transient current. Fig. 5(e) shows the B phase short-circuit fault simulation transient current. Fig. 5(f) shows the C phase short-circuit fault simulation transient current.

Fig. 5Waveform of transient voltage and current of three phase short circuit fault simulation

Fig. 5 shows that both the voltage and current of this system changed after a fault. The 1 Ω and 25 Ω simulated transient voltages showed the same trend, while the ABC three-phase short-circuit simulated voltage showed smaller fluctuations in the 0.07-0.1 s time range. Similarly, the 1 Ω and 25 Ω simulated transient currents showed almost no change in the 0.07-0.1 s time range. Similarly, the trends of the transient currents for the 1 Ω and 25 Ω simulations are consistent, but the ABC three-phase short circuit simulated currents show little variation in the 0-0.1 s time range and regular variation after 0.1 s. The results show that for a three-phase short circuit, the magnitude of this fault resistance has a limited effect on the three-phase voltage, but a greater effect on the three-phase current.

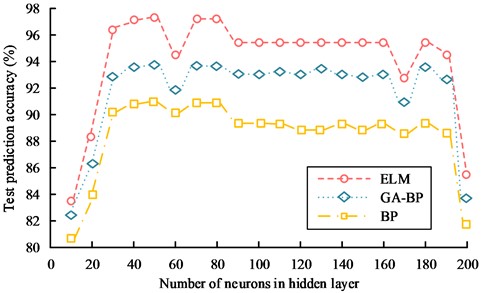

Due to the mechanistic nature of ELM learning, the number of neuron nodes is then selected after several matching trials. The effect of number of neurons in hidden layer on this ELM performance is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6The influence of the number of hidden layer neurons on the performance of three algorithm models

Fig. 6 illustrates how the ELM learning machine performs best when the number of hidden layer neuron nodes is set to 50, resulting in a test set prediction accuracy of approximately 97.86 %. As the number of neurons increased, the model's ability to generalise started to decrease. In the range of 85-160 neurons, the correct prediction rate was maintained at around 95.78 %. At 165 neurons in the hidden layer, it dropped to 92.34 %. After the number of neurons exceeded 180, the correct prediction rate of the model dropped sharply and overfitting occurred. Similarly, the prediction performance of the BP network model and the GA-BP network fault diagnosis model was affected by the number of neurons in the hidden layer, similar to that of the ELM-based model. When the number of hidden layers reached 50, the prediction accuracy of these two models was the highest, around 91.56 % and 93.69 % respectively. As the number of neurons in the hidden layer increases, the predictive ability of both models tends to decrease and eventually overfitting occurs. The experimental results showed that the ELM-based fault diagnosis model for building electrical systems was superior to other models in terms of prediction accuracy.

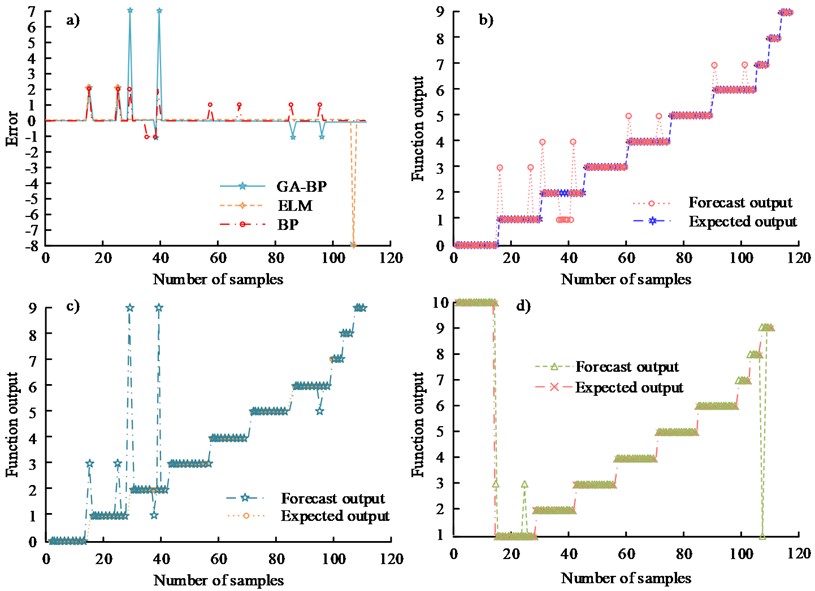

The 12 feature vectors were used as input to the fault diagnosis and monitoring model for this building electrical system and the studied ELM algorithm-based model was compared with the BP model and the Genetic Algorithm-Back Propagation (GA-BP) fault diagnosis model based on the Genetic Algorithm Optimization BP algorithm. The classification errors and classification outputs of the networked distribution network faults obtained from these three models are shown in Fig. 7. NOTE: Fig. 7(a) shows the classification error of three models. Fig. 7(b) shows the BP model classification output. Fig. 7(c) shows the GA-BP model classification output. Fig. 7(d) shows the ELM model classification output.

Fig. 7Fault classification results of distribution network based on ELM, BP and GA-BP algorithms

From Fig. 7(b), it can be seen this BP algorithm based model can accurately achieve the classification of 10 faults with a maximum error of 2. From Fig. 7(c), the GA-BP neural network based model can accurately achieve the classification of 10 faults with a maximum error of 7. From Fig. 7(d), the ELM algorithm based model can accurately achieve the classification of 10 faults with a maximum error of 2. From Fig. 7(a) and Fig. 7(b), it can be inferred that the model's classification accuracy for this sample is 89.09 %. Out of 110 samples, 12 of the anticipated results based on the BP neural network model had incorrect classifications. From Fig. 7(a) and Fig. 7(c), it can be seen that the predicted output based on the GA-BP algorithm model and the actual output error in 110 samples, there are 7 samples with Therefore, the classification accuracy of the model for this sample is 93.64 %. From Fig. 7(a) and Fig. 7(d), the predicted output of the ELM-based model is misclassified in only 2 out of 82 samples. Therefore, the classification accuracy of the model for this sample is 97.56 %. The results show that the ELM algorithm-based fault diagnosis technology and monitoring method for building electrical systems has a higher classification accuracy than both BP network and GA-BP model fault diagnosis models, showing better generalization ability and robustness.

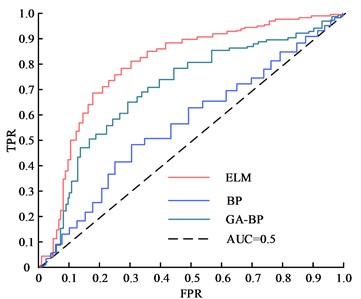

To further validate the proposed method for fault detection in building electrical systems, it was compared with the BP and GA-BP models, respectively. The plot of the FPR-TPR binary is called the ROC curve, which makes it easier to determine the ability of a classifier to detect samples at a given threshold. The ROC curves of the three models are shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8ROC curves of three models

From Fig. 8, the AUC values of the research ELM algorithm-based model with BP model and GA-BP model are 0.92, 0.87 and 0.63, respectively. The results indicated that the research model was better than other two algorithm models for fault discrimination of building electrical systems.

4.2. Comparative analysis of performance of three fault diagnosis models for building electrical systems

Finally, to study the accuracy of the proposed methods for fault diagnosis of building electrical systems, they are compared with the BP and GA-BP models respectively. In order to avoid chance in calculation and to lessen the impact of random initial values on the results, the three methods are computed ten times to take the average value. Their performance comparison results are shown in Table 3. As the connection weights of its input and implied layers in ELM theory are random in nature.

Table 3Performance comparison results of three models

Algorithm index | ELM | GA-BP | BP |

Activation function | Sigmoid | Sigmoid | Sigmoid |

Number of neurons | Iterative calculation | Manual setting | Manual setting |

Value (weight, threshold) | Random | Genetic algorithm optimization+gradient descent iteration | Gradient descent iteration |

Root mean square error | 0.3521 | 0.5836 | 0.7923 |

Total accuracy of fault identification | 97.27 % | 93.64 % | 89.09 % |

Algorithm time consuming | 0.201s | 31.456 s | 0.475 s |

Table 3 shows that the ELM algorithm has the lowest value for the root mean square error of fault classification, which is 0.3521. The GA-BP and BP algorithms have lower RMS errors of 0.2315 and 0.4402 lower respectively. The overall accuracy of ELM fault identification is much higher than the other two algorithms, being 3.63 % higher than the GA-BP algorithm and 8.18 % higher than the BP algorithm. In addition, in terms of running time, the ELM algorithm takes only 0.427 s, which is faster than the other two algorithms. In summary, the ELM algorithm has certain advantages over traditional algorithms in terms of recognition and running time.

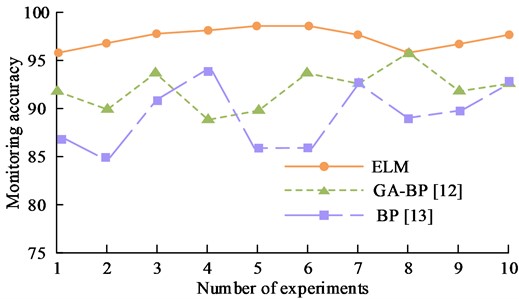

As can be seen from Fig. 9, BP has a worse performance in terms of accuracy, comparing its results with those of ELM, the RMSE of BP is 0.4402 higher. The RMSE of the GA-BP model is 0.2315 higher than that of the ELM-based model. The ELM-based model has a 97.27 % correct rate in fault discrimination, which is better than other traditional or extended fault diagnosis monitoring models. In addition, the ELM model is faster in terms of model training time than the other models compared. As shown in Fig. 9, the monitoring accuracy of the research model is compared with the two more advanced fault diagnosis models in literature [12] and literature [13].

Fig. 9Monitoring accuracy comparison results of different models

From Fig. 9, the ELM model data predicts small fluctuations, tends to be smooth and has a better monitoring accuracy of up to 98.6 %. Therefore, the proposed method can effectively and accurately diagnose and monitor the fault categories of building electrical systems and meet the real-time requirements. In summary, the ELM algorithm-based fault diagnosis and monitoring model for building electrical systems is optimal in terms of generalization performance, correct prediction rate and computation speed, and diagnosis and monitoring accuracy.

5. Conclusions

Both the distribution system and the electricity consuming equipment will suffer more damage from a fault in the building electrical system. The study proposes to build a fault diagnosis and monitoring model for building electrical systems using the ELM algorithm by combining the actual operating conditions of building electrical systems with the advantages and disadvantages of conventional neural networks for fault identification. Results showed this model based on the ELM algorithm can accurately achieve 10 classifications of faults with a maximum error of 2. The classification accuracy of the model for this experimental sample is 97.56 %, which is higher than the classification accuracy of BP models and GA-BP fault diagnosis models, showing better generalization ability and robustness. When the hidden layer's number of neuron nodes was set to 50 for the ELM learning machine to categorize this data, its test set prediction accuracy was roughly 97.86 %. The AUC value of the model based on the ELM algorithm for the study was 0.92 respectively, which is good for fault discrimination of faults in building electrical systems. The RMSE of the model is 0.3521, which is smaller than the BP models and GA-BP fault diagnosis models. The ELM algorithm-based model is faster in identifying and diagnosing faults than other algorithmic models, with a fault discrimination accuracy rate of 97.27 % and a computation time of only 0.201 s. At the same time, the ELM model in this study has a good fault monitoring accuracy of up to 98.6 % for building electrical systems. Although the ELM-based building electrical fault diagnosis method in this research has achieved good results, there are still shortcomings. In the actual scene, just one lighting exhaust bus was modeled, and the malfunction on this bus was reproduced. Each component of the building electrical system should be researched in the upcoming work in order to create a comprehensive building electrical fault diagnosis system. A further area that needs to be addressed in future research is the residual life prediction of building electrical equipment, which is a crucial component of the dependability of building electrical lines.

The fault characteristic quantity data were input into three fault identification intelligent algorithms to obtain the recognition effect of the three algorithms. The comparison results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4Fault diagnosis effect of three algorithms in different environments

Contrast item | BP (%) | GA-BP (%) | ELM (%) |

Single-phase grounding | 57.14 | 85.71 | 85.72 |

Two-phase short circuit | 64.29 | 78.57 | 100 |

Two-phase short-circuit grounding | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Single-phase arc grounding | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Two-phase arc short circuit | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Single-phase absence | 89.09 | 93.64 | 97.27 |

Overload fault | 100 | 100 | 96 |

From Table 4, for distribution network fault identification, BP neural network shows a certain identification speed and generalization ability. However, the accuracy of single-phase short-circuit fault identification is low, only 57.14 %. In line with its theory, the GA-BP neural network has great generalization and accuracy abilities. However, the naturally slow computational speed of the genetic algorithm is exacerbated when the BP neural network is optimized. It can be seen that the computational speed of the GA-BP algorithm is far behind that of the BP neural network and the ELM extreme learning machine. In addition, the ELM method still performs well in fault detection compared to the GA-BP algorithm, with the exception of overload fault diagnosis, which has a 4 % difference. For other fault types, the diagnostic performance of the ELM is much better than other models.

References

-

B. Yu and Z. Zhang, “Adaptive Configuration method of low-frequency electromechanical sampling information in building electrical system,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, Vol. 2021, pp. 1–8, May 2021, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6624330

-

M. Soleymani, A. Asakereh, and S. M. Safieddin Ardebili, “A GIS-based multi-criteria fuzzy approach to select a suitable location for a MSW-based power plant and landfill: a case study, Khuzestan province, Iran,” Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, Vol. 194, No. 3, pp. 1–20, Mar. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-09809-9

-

X. Ren et al., “Design of multi-information fusion based intelligent electrical fire detection system for green buildings,” Sustainability, Vol. 13, No. 6, p. 3405, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063405

-

S. Noye, R. North, and D. Fisk, “A wireless sensor network prototype for post-occupancy troubleshooting of building systems,” Automation in Construction, Vol. 89, pp. 225–234, May 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.12.025

-

R. Yuan et al., “Robust fault diagnosis of rolling bearing via phase space reconstruction of intrinsic mode functions and neural network under various operating conditions,” Structural Health Monitoring, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 846–864, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1177/1475921722109113

-

G. Liu, X. Wei, and S. Zhang., “Analysis of epileptic seizure detection method based on improved genetic algorithm optimization back propagation neural network,” Journal of Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 24–32, 2019, https://doi.org/10.7507/1001-5515.201806039

-

A. Alcañiz, M. M. Nikam, Y. Snow, O. Isabella, and H. Ziar, “Photovoltaic system monitoring and fault detection using peer systems,” Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications, Vol. 30, No. 9, pp. 1072–1086, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1002/pip.3558

-

X. Liu, J. Du, and Z.-S. Ye, “A condition monitoring and fault isolation system for wind turbine based on SCADA data,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 986–995, Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/tii.2021.3075239

-

J. Pang, Z. Yu, and X. Chen, “Research on thermal imaging fault detection system based on Weibull distributed electrical system,” in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 1941, No. 1, p. 012037, Jun. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1941/1/012037

-

Y. Yang, H. Wu, and J. Ma, “Electrical system design and fault analysis of machine tool based on automatic control,” International Journal of Automation Technology, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 547–552, Jul. 2021, https://doi.org/10.20965/ijat.2021.p0547

-

S. Xiangyang, “Research on fault diagnosis of B737 aircraft fuel system based on improved BP neural network,” Mathematical Models in Engineering, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 11–16, Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.21595/mme.2019.20536

-

P. Zhang, Z. Cui, Y. Wang, and S. Ding, “Application of BPNN optimized by chaotic adaptive gravity search and particle swarm optimization algorithms for fault diagnosis of electrical machine drive system,” Electrical Engineering, Vol. 104, No. 2, pp. 819–831, Apr. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-021-01335-0

-

Y. Han, W. Qi, N. Ding, and Z. Geng, “Short-time wavelet entropy integrating improved LSTM for fault diagnosis of modular multilevel converter,” IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, Vol. 52, No. 8, pp. 7504–7512, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/tcyb.2020.3041850

-

K. Yan, Y. Zhang, Y. Yan, C. Xu, and S. Zhang, “Fault diagnosis method of sensors in building structural health monitoring system based on communication load optimization,” Computer Communications, Vol. 159, pp. 310–316, Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2020.05.026

-

W. H. Elashmawi, N. A. Kotp, and G. E. Tawel, “A novel proposed neural network MAD (monitoring, analysis and diagnose) model for industrial gas turbine,” International Journal of Soft Computing, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 92–101, 2018, https://doi.org/10.36478/ijscomp.2018.92.101

-

A. Sharma, L. Mathew, S. Chatterji, and D. Goyal, “Artificial intelligence-based fault diagnosis for condition monitoring of electric motors,” International Journal of Pattern Recognition and Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 34, No. 13, p. 2059043, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1142/s0218001420590430

-

M. Talaat, M. H. Gobran, and M. Wasfi, “A hybrid model of an artificial neural network with thermodynamic model for system diagnosis of electrical power plant gas turbine,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 68, pp. 222–235, Feb. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2017.10.014

-

H. Xing, S. Junyi, and H. Jin, “The casualty prediction of earthquake disaster based on Extreme Learning Machine method,” Natural Hazards, Vol. 102, No. 3, pp. 873–886, Jul. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-03937-6

-

T. Kassa Mersha and C. Du, “Active damping control of HEVs using Ansys and Matlab/Simulink software,” Journal of Vibroengineering, Vol. 24, No. 7, pp. 1340–1353, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2022.22511

-

N. Sharma, G. Mademlis, Y. Liu, and J. Tang, “Evaluation of operating range of a machine emulator for a back-to-back power-hardware-in-the-loop test bench,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, Vol. 69, No. 10, pp. 9783–9792, Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2022.3142421

-

S. Tolani, S. Joshi, and P. Sensarma, “Dual-loop digital control of a three-phase power supply unit with reduced sensor count,” IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 367–375, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/tia.2017.2761832

-

Y. Ji and Z. Kang, “Three‐stage forgetting factor stochastic gradient parameter estimation methods for a class of nonlinear systems,” International Journal of Robust and Nonlinear Control, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 971–987, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/rnc.5323

-

L. Wang, J. Xu, Q. Chen, Z. Chen, X. Geng, and K. Lin, “Improved PWM strategies to mitigate dead-time distortion in three-phase voltage source converter,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, Vol. 37, No. 12, pp. 14692–14705, Dec. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/tpel.2022.3192255

-

F. Yonga, C. Welba, T. Louossi, and N. Djongyang, “A new control approach of a three-phase inverter two levels,” Open Journal of Energy Efficiency, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 55–70, 2022, https://doi.org/10.4236/ojee.2022.113005

-

D. Yang, Y. Lv, R. Yuan, H. Li, and W. Zhu, “Robust fault diagnosis of rolling bearings via entropy-weighted nuisance attribute projection and neural network under various operating conditions,” Structural Health Monitoring, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 2890–2909, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217221077414

-

Kasliono, Suprapto, and F. Makhrus, “Point based forecasting model of vehicle queue with extreme learning machine method and correlation analysis,” International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 11–22, Jun. 2021, https://doi.org/10.5815/ijisa.2021.03.02

-

T. Ouyang, “Feature learning for stacked ELM via low-rank matrix factorization,” Neurocomputing, Vol. 448, pp. 82–93, Aug. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2021.03.110

-

L. Xia, P. Hu, K. Ma, and L. Yang, “Research on measurement modeling of spherical joint rotation angle based on RBF-ELM network,” IEEE Sensors Journal, Vol. 21, No. 20, pp. 23118–23124, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2021.3106303

-

S. Jovic, A. Cukaric, A. Raicevic, and P. Tomov, “Assessment of electronic system for e-patent application and economic growth prediction,” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 2019.

-

Ho Pham Huy Anh, “Real-time identified chaotic plants using neural enhanced learning machine technique,” Engineering Computations, Vol. 38, No. 6, pp. 2810–2832, Jul. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1108/ec-01-2020-0049

-

A. Cordero, J. R. Torregrosa, and F. Zafar, “Approximating the inverse and the Moore‐Penrose inverse of complex matrices,” Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences, Vol. 42, No. 17, pp. 5920–5928, Nov. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/mma.5879

-

M. Kim, “The generalized extreme learning machines: Tuning hyperparameters and limiting approach for the Moore-Penrose generalized inverse,” Neural Networks, Vol. 144, pp. 591–602, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2021.09.008

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.