Abstract

Periodontal disease can be defined as a chronic inflammatory process primarily associated with the accumulation of dental biofilm that affects the supporting periodontal and protective tissues of the periodontium, including root cementum, gingiva, alveolar bone, and periodontal ligament. However, evidence indicates that non-microbial factors, such as occlusal trauma, may also contribute to its progression. In this context, the need to investigate the possible correlation between loss of periodontal attachment and the presence of occlusal alterations, particularly those arising from repetitive traumatic loading, is emphasized. The present study aimed to critically analyze the existing scientific literature on the relationship between occlusal trauma and periodontal impairment. A total of twenty-eight articles were included, selected from the SciELO, PubMed, and Google Scholar databases, published between 1999 and 2025, using terms such as occlusal trauma, periodontal disease, inflammatory mediators, and periodontal inflammation. The qualitative analysis aimed to highlight convergences and divergences in the findings, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of the factors that influence periodontal disease. The study revealed that, although occlusal trauma is not a causative factor of the disease, it exacerbates the destruction of already compromised tissues, highlighting the need for an integrated therapeutic approach for its management.

1. Introduction

The development of periodontal disease is intricately linked to inadequate oral hygiene, which allows dental biofilm to accumulate in the oral cavity. However, the literature indicates that external factors can predispose individuals to the progression of periodontal diseases in conjunction with poor hygiene [1]. These factors can be systemic (e.g., diabetes and obesity), lifestyle-related (e.g., smoking), or local, such as occlusal trauma [2]. Occlusal trauma is a condition arising from excessive forces associated with occlusal pathologies, such as bruxism and teeth clenching [3]. These pathologies can increase and deregulate the forces of mandibular movements, inducing microlesions within periodontal structures, including the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone [4].

In response to these microlesions, inflammatory mediators are synthesized to contain these invading microorganisms. Consequently, symptoms of inflammation develop, including itching, edema, pain, and bone resorption. In more severe cases, the inflammatory response can lead to the destruction of the periodontal ligament fibers and tooth loss [5].

Excessive occlusal loading on these tissues can accelerate the progression of periodontal disease, as the breakdown of microtissue lesions into phospholipids activates the enzyme phospholipase A2, which transforms these phospholipids into arachidonic acid. Subsequently, other enzymes, such as cyclooxygenases (COX I and COX II), transform arachidonic acid into inflammatory mediators (prostaglandins, prostacyclins, and thromboxane), which signal tissue damage to leukocytes, indicating the need for immune support to combat bacteria [6].

Among these mediators, prostaglandins are particularly significant for their ability to intensify the inflammatory process and contribute directly to periodontal degradation. Their action promotes gingival retraction and displacement of the tooth from the alveolar bone, resulting in mobility and, subsequently, tooth loss [7].

This study constitutes a literature review that aims to synthesize the converging and diverging findings regarding the relationship between periodontal disease and occlusal trauma.

2. Methodology

This study is characterized as a systematic integrative review, aiming to analyze the scientific literature on the impact of occlusal trauma on the periodontium. Data collection was conducted between November 2023 and March 2025, using PubMed, SciELO, and Google Scholar databases. The search was conducted using the following terms: occlusal trauma, periodontal disease, inflammatory mediators, and periodontal inflammation. The inclusion criteria were original articles and scientific reviews published between 1999 and 2025.

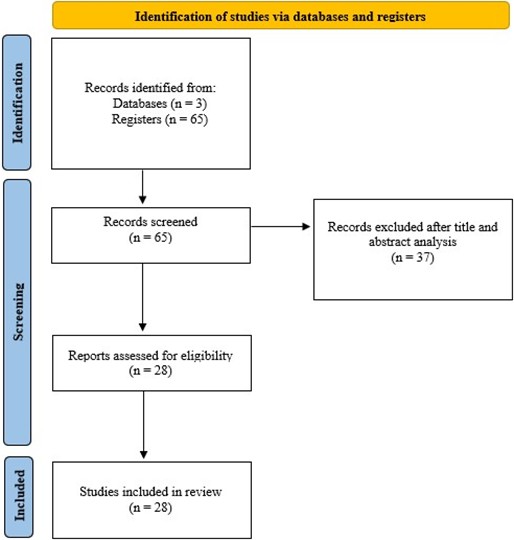

Initially, sixty-five articles were identified through database indexing, based on their titles and abstracts. After reading and conducting a detailed analysis of the abstracts, a careful selection was conducted, resulting in twenty-eight articles that met the relevance criteria for this study. The list was based on temporal criteria and the relevance of the articles to the research objectives. These constituted the final sample for qualitative synthesis, as illustrated in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1PRISMA diagram

A formal methodological quality assessment tool (such as CASP or STROBE) was not considered, since the focus of the review was on the qualitative analysis of the content of the studies, with an emphasis on theoretical relevance and coherence with the research objectives. To ensure reproducibility, the keywords and filters applied during the search were documented, and the selection of articles followed a systematic approach. The analysis of the texts was carried out in several stages: exploratory reading of the articles; selection of the material aligned with the study objectives; critical analysis and interpretation of the data found in the selected articles; and interpretative reading, which preceded the writing phase, ensuring that the selected information was pertinent and directly related to the impact of occlusal trauma on the periodontal inflammatory process and periodontal disease. The analysis of the collected data was performed qualitatively, with the synthesis of the most relevant information on how occlusal trauma influences periodontal inflammation and its impact on the progression of periodontal disease. The organization of the results followed a logical structure, with relevant quotes extracted from the articles to support the arguments and conclusions presented.

3. Results

Malocclusion is a morphological condition and may be accompanied by functional alterations. Malocclusion can be defined as a significant deviation from what is understood as normal occlusion. It can be classified, using the Angle system, based on the anteroposterior relationships of the mandible and maxilla, into three distinct types. When the molars are in the correct position, it is called Class I; when there is a retroprojection of the mandible, it is called Class II; and when there is a forward projection of the mandible, it is called Class III [1].

Poor positioning, misalignment, or crowding of teeth; mouth breathing; some occlusal interferences; and parafunctional habits are factors that, if present, may predispose an individual to periodontal disease [1].

3.1. Effects of occlusal trauma on the stomatognathic system

Occlusal trauma affects various tissues of the tooth attachment system and can occur in healthy gingiva or conditions limited by periodontal disease. Primary occlusal trauma is caused by excessive forces on teeth with normal periodontal support [8]. It can lead to complications, such as tooth cracks, tooth wear, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and varying degrees of tooth mobility, which can range from mild to severe [4]. On the other hand, secondary occlusal trauma occurs in teeth with limited periodontal support [8]. Therefore, there is an association between occlusal trauma and periodontal disease [9].

3.2. Periodontal ligament and its response to occlusal forces

3.2.1. Function of the periodontal ligament

The periodontal ligament plays a crucial role in regulating the structure and function of the periodontium, serving as a fundamental protector of the gingiva against mechanical stress and transmitting the force of mastication to the adjacent alveolar bone [12]. Its cells can produce important molecular regulators, such as cytokines and growth factors, influencing the metabolism and location of cells involved in the formation of bone, cementum, and ligament [6].

3.2.2. Response to occlusal forces

The integrity of periodontal tissues, such as cementum, alveolar bone, and periodontal ligament, is partially coordinated by the expression of periostin. This key molecule is released in response to occlusal forces, with occlusion triggering a complex interaction between biological molecules and various cells in different tissue domains [6].

3.2.3. Associated regenerative process

It has been reported in previous studies that corticotomy, in combination with regenerative techniques, can provide benefits for both soft and hard tissues of the periodontium, including the regeneration of these tissues [13].

3.3. Occlusal trauma as a cofactor of periodontitis

3.3.1. Relationship between malocclusion and periodontal disease

Malocclusion is associated with the etiopathogenesis of periodontal disease and may influence plaque accumulation, in addition to having an impact on occlusal trauma. Studies mention the effect of occlusal force on periodontal health, while periodontal health can also affect occlusion [14]. Other studies also mention the relationship of malocclusion as a cofactor for periodontitis. N. Tagger-Green et al. (2023) [15] state that “work in animal models has implicated excessive occlusal forces and occlusal trauma as co-destructive factors for periodontitis”.

3.3.2. Periodontal changes caused by traumatic occlusal forces

Changes in periodontal tissues caused by traumatic occlusal forces can influence tissue responses. The longer this force continues, the more damaging it becomes to the periodontium. These changes lead to osteoclastic stimulation and bone resorption within the medullary spaces, particularly in the area surrounding the periodontal ligament [6].

When traumatic occlusal forces exceed the adaptive capacity of the tissues, they trigger rapid alterations within the periodontal ligament. This process involves the release of substances such as interleukin-1 and prostaglandins, activating osteoclasts. Mechanical stress triggers the release of proteins in the periodontal ligament, resulting in mast cell degranulation and subsequent inflammatory processes.

The application of force to the periodontal ligament leads to an inflammatory infiltrate, which promotes an acidic environment that is favorable to the attraction of osteoclasts and bone resorption [6].

Traumatic occlusion and increased disruption of periodontal ligament fibers will result from periodontitis combined with migrated teeth [13].

3.3.3. Orthodontic implications

For adult patients who have periodontal disease and require orthodontic treatment, it is also important to assess their periodontal health. Therefore, careful planning is necessary to achieve balanced occlusal adjustment while avoiding excessive forces that could worsen the patient’s situation [16]. Therefore, when starting orthodontic treatment, it is important that the professional, in addition to focusing on the aesthetics of the smile, also ensures that the periodontal health is adequate so that existing problems do not worsen [17].

3.3.4. Occlusal adjustment and its periodontal control

Occlusal adjustments can bring considerable improvements in gingival health, preventing damage caused by malocclusion [10]. To improve prognosis and delay or stop the progression of periodontitis, occlusal adjustment may be necessary, especially when signs of occlusal trauma are present; however, it does not replace conventional periodontal treatment to resolve inflammation caused by bacterial plaque [8]. To improve the level of clinical attachment, occlusal adjustment can also be performed, especially in teeth with mobility or with premature contacts [11].

By adjusting the contacts between the teeth so that the occlusal forces are balanced, there may be an improvement in the health of the periodontal tissues, as the occlusal adjustment will remove the excessive forces due to a malocclusion [10].

3.4. Cellular mechanisms of bone resorption induced by occlusal trauma

3.4.1. RANKL and HMGB1

It is essential to comprehend the cellular mechanisms underlying bone resorption caused by occlusal trauma. RANKL plays a crucial role in the formation of osteoclasts, a cell type that is responsible for bone resorption. Damaged cells release HMGB1, which plays a role in inducing RANKL expression. In this study, conducted in mice, it was observed that the application of occlusal force increased the expression of RANKL and HMGB1, particularly in the affected periodontal tissues. These findings suggest that HMGB1 accelerates bone resorption under conditions of traumatic occlusion by increasing RANKL expression [18].

3.4.2. Inflammatory signaling pathways

The Hippo signaling pathway has a modulatory function, enabling it to regulate organ size, tissue physiological balance, and tumor development. One means of activating this pathway is mechanical force. Activation of the Hippo-YAP pathway due to occlusal trauma is associated with bone remodeling, inflammatory reactions in cells, and periodontal bone resorption [19].

Occlusal trauma triggers the activation of the IKK-NF-κB signaling pathway, which contributes to the inhibition of osteogenic differentiation and the suppression of gene expression associated with bone formation. Additionally, the activation of IKK-NF-κB interferes with the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, a crucial pathway in bone formation, leading to decreased bone formation due to impaired osteoblast differentiation [20].

3.4.3. Inhibition of regeneration by non-coding RNA

Traumatic forces suppress the expression of DANCR, a non-coding long-chain RNA that acts on the stem cells of the periodontal ligament, inhibiting their osteogenic differentiation at the moment NF-κB is activated [21].

3.4.4. Tissue plasticity and orthodontic movement

The periodontal ligament and the alveolar bone are the main tissue elements that change during this tooth movement, which is conducted through mechanical forces that, when applied, can allow the activation of bone and related cells. These tissues exhibit plasticity that enables the physiological and orthodontic movement of the teeth, allowing for the formation or reabsorption of bone and facilitating tooth movement. This highlights the importance of periodontal health for successful and stable orthodontic outcomes [22].

3.5. Summary of results

As shown in Table 1, it is noted that the studies vary in terms of the year of publication, population investigated, and primary outcomes analyzed.

4. Discussion

Siqueira et al. (2023) [23] state that recent studies reinforce the notion that occlusal trauma, although not an initiating factor of periodontitis, can exacerbate tissue destruction in already compromised tissues.

In the articles studied, there was consensus among the authors regarding the understanding of occlusal trauma. Fan et al. (2018) [8] described occlusal trauma as an alteration that occurs in various tooth-supporting tissues due to excessive occlusal forces. Tomina et al. (2021) [4] also mentioned the definition and distinction between primary and secondary occlusal trauma. According to Fan et al. (2018) [8], primary occlusal trauma can lead to complications, including cracked teeth, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and tooth wear; and may even cause tooth mobility.

Table 1Summary of results

Reference | First author | Year | Population studied/Type of study | Findings |

[1] | Ruthineia Diogenes Alves Uchôa Lins | 2011 | Thirty adult patients (≥ 18 years), both sexes | There was no clear evidence of a direct relationship between malocclusions and progression to periodontitis |

[2] | Thomas E Van Dyke | 2005 | Review of studies | Occlusal trauma is a contributing factor that can alter the periodontium in vulnerable individuals, but it is not sufficient on its own to cause the disease |

[3] | WW Hallmon | 1994 | Review of studies | Occlusal trauma can aggravate already established periodontitis, but it is not enough to cause it on its own |

[4] | Dario Tomina | 2021 | Forty young patients (20-35 years), systemically healthy, with type 1 gingival recession (RT1) and without inflammation/periodontitis | There is a statistically significant association between eccentric occlusal interferences (mainly in lateral excursions) and the presence of localized gingival recession, even in the absence of periodontitis |

[6] | Euloir Passanezi | 2019 | Review of studies | Occlusal trauma does not initiate periodontitis but may be a cofactor in its progression, and occlusal therapy helps manage existing disease |

[8] | Jingyuan Fan | 2018 | Review of studies | Occlusal trauma and excessive forces do not initiate periodontitis but may contribute to connective tissue loss in existing cases, with occlusal therapy being beneficial for patient comfort and reduced mobility |

[9] | Jorge Ivan Campino | 2021 | Retrospective case-control study (167 cases with periodontitis, 205 controls without periodontitis) | Occlusal trauma is strongly associated with periodontitis, even after adjusting for other variables |

[10] | F. Meynardi | 2018 | Case report of a 60-year-old patient with severe gingival inflammation and functional overload, combined with a review of theories | Periodontal disease is a chronic atrophic-dystrophic syndrome, mainly due to biomechanical dysfunction (occlusal trauma), and not only bacterial infection. Occlusal adjustment improves the condition |

[11] | Henrik Dommisch | 2022 | Review of studies | Dental retention can improve masticatory ability, and occlusal adjustment is suggested to equalize occlusal stress in teeth exposed to traumatic forces |

[12] | Dandan Pei | 2018 | Finite element model (FEM) of the tooth-LPD-bone complex | The periodontal ligament (PDL) protects the alveolar bone from mechanical impacts by absorbing and distributing stress. Understanding its energy conversion is vital to understanding dental diseases such as concussion and occlusal trauma |

[13] | Meihua Chen | 2022 | Case report of a 35-year-old male patient with periodontitis, thin periodontal phenotype, and anterior crossbite | Sequential treatment of soft and hard tissue after correction of traumatic occlusion with clear aligners can effectively improve periodontal support in patients with periodontitis |

[15] | Naama Fridenberg | 2023 | Retrospective clinical study | Radiographic signs of excessive occlusal forces are associated with marginal bone loss |

[16] | Ayako Taira | 2018 | Case report of a patient with moderate to extensive chronic periodontitis associated with occlusal trauma | Comprehensive and appropriate occlusal reconstruction therapy is necessary for the orthodontic treatment of adult patients with malocclusion and periodontal disease associated with occlusal trauma |

[17] | R. Boar | 2020 | Patients seeking orthodontic treatment in the southwest region of Saudi Arabia | The study revealed a correlation between malocclusion and the prevalence of periodontal disease in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment for aesthetic reasons |

[18] | Mika Oyama | 2020 | Mice | HMGB1 protein, released from damaged tissues, accelerates bone resorption induced by occlusal trauma in mice and may promote bone resorption in both periodontitis and occlusal trauma |

[19] | Weiyi Pan | 2019 | BALB/cJ mice and cell lines (L929 and MC3T3-E1) | Traumatic occlusion aggravates bone loss during periodontitis and activates the Hippo-YAP pathway |

[20] | Weizhe Xu | 2019 | MC3T3-E1 cells. (pre-osteoblasts) | Occlusal trauma inhibits osteoblast differentiation and bone formation through IKK-NF-κB signaling |

[21] | Qian Lu | 2019 | MCTT3-E1 cells | Traumatic compressive stress inhibits osteoblast differentiation through downregulation of the long non-coding RNA Dancr |

[22] | Suami Gonzalez Rodriguez | 2019 | 41-year-old female patient with controlled chronic periodontitis (case report) | Orthodontic treatment corrected anomalies in tooth position and occlusion, increased periodontal insertion, decreased mobility, and promoted radiographic bone repair |

Passanezi et al. (2019) [6] and Pei et al. (2018) [12] mention that the periodontium has fibers responsible for receiving occlusal forces and transmitting them to the alveolar bone. In other words, they affirm that they have a significant role in occlusion. The cells present in them can produce important metabolic regulators, influencing the metabolism and location of the cells involved in forming the supporting periodontium. Passanezi et al. (2019) [6] also mention all the changes in the periodontium due to excessive occlusal forces, which can cause stimulation of bone resorption and the release of inflammatory substances. Therefore, Passanezi et al. (2019) [6] were important authors in this study, as they mentioned all the periodontal changes caused by traumatic occlusal forces, showing an association between periodontal disease and occlusal trauma.

Authors such as Oyama et al. (2021) [18] mention in their studies the relationship between occlusal trauma and bone resorption. Oyama et al. (2021) [18] found in their research that the application of occlusal force leads to an increase in the expression of RANKL and HMGB1. RANKL has a function in bone resorption. HMGB1, on the other hand, plays a role in inducing RANKL expression, thereby accelerating bone resorption. This present study was conducted in mice; therefore, it is imperative to understand the cellular and molecular interactions that occur in the human periodontium, and it is worth noting that they may present distinct characteristics. However, understanding these pathways is essential to comprehend how occlusal trauma can function as a cofactor in periodontitis by promoting osteoclast activation and inhibiting bone formation, as also suggested by the IKK-NF-κB pathway, studied by W. Pan et al. (2019) [19], and the Hippo-YAP pathway, studied by W. Xu et al. [20]. The Hippo-YAP pathway is associated with bone remodeling, inflammatory reactions in cells, and periodontal bone resorption. The IKK-NF-kB pathway inhibits the expression of genes associated with bone formation.

In the clinical context, this understanding indicates the relevance of an occlusal evaluation in patients with periodontal diseases. Innovations in imaging technology, such as magnetic resonance imaging (Dewake et al., 2023 [24]), provide a promising tool for a more objective analysis of the periodontal ligament space, enabling earlier and more accurate detection of occlusal trauma. For dentists and periodontists, this implies that interventions can be conducted more appropriately, potentially avoiding the aggravated progression of the disease.

The interdisciplinary approach, as discussed by Pereira et al. (2023) [25] and corroborated in a recent consensus by Zhong et al. (2025) [26], is necessary. For patients undergoing orthodontic treatment who have periodontal diseases, it is essential to ensure, through joint planning, that the forces applied during treatment do not worsen an already affected condition but rather help to stabilize and maintain periodontal health. Fan et al. (2018) [8] and Meynardi et al. (2018) [10], in their studies, show that occlusal adjustment, although it cannot replace conventional periodontal therapy, is a complement to improve the mechanical environment and reduce stress on the supporting tissues, which can delay the progression of periodontitis and improve the prognosis, especially in teeth that are mobile or have premature contacts. Studies from 2025 also reinforce the importance of an interdisciplinary approach in the treatment of patients with periodontitis and occlusal trauma. Zhong et al. (2025) [26] highlight a clinical consensus that guides the conduct in patients with periodontal involvement, emphasizing the need for careful planning to prevent worsening of the clinical condition.

Furthermore, Kumar et al. (2025) [27] present a clinical case in which occlusal trauma resulted in a periodontal abscess, demonstrating that, in some cases, isolated management of inflammation is insufficient if the occlusion remains decompensated.

Finally, Liu et al. (2025) [28] identify the role of the plasminogen/plasmin system as a mediator of bone resorption in response to occlusal trauma, pointing to a possible new therapeutic route to reduce local inflammatory effects.

5. Conclusions

This literature review shows that the relationship between occlusal trauma and periodontal disease is intrinsically complex, involving mechanical, inflammatory, and structural factors that act synergistically in the destruction of dental support tissues. Occlusal trauma intensifies the periodontal inflammatory response, accelerating attachment loss and bone resorption, particularly in environments already compromised by the presence of bacterial biofilm and periodontal inflammation.

The conclusions of this study corroborate the literature by indicating that, although isolated occlusal adjustment can contribute to the reduction of traumatic forces exerted on the periodontium, its clinical application should be carefully indicated and consistently associated with the etiological control of periodontal disease. Occlusal adjustment, when performed appropriately, has been demonstrated to be effective in stabilizing cases with increased mobility and in patients with clinical signs of occlusal trauma, such as tooth wear, tooth fractures, and changes in muscle function.

Regarding research perspectives, it is essential to deepen knowledge about the molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate the periodontium's response to occlusal trauma. Understanding the roles of inflammatory cytokines, bone mediators, and cellular signaling pathways may support the development of more targeted therapies aimed at tissue regeneration and the containment of the destructive process. Longitudinal clinical investigations, combined with experimental models that have a high capacity for controlling the variables involved, are essential for elucidating the effects of different intensities, durations, and directions of occlusal forces on both healthy and compromised periodontal tissues.

From a therapeutic perspective, the results suggest the need for expanded multidisciplinary clinical interventions that extend beyond conventional scaling and root planning approaches, incorporating occlusal modulation strategies and control of parafunctional habits. The importance of integration between periodontics and orthodontics is highlighted, especially in cases where tooth movement can redistribute occlusal forces and reestablish functional patterns that are more favorable to periodontal stability.

Thus, it is concluded that effective clinical management of the association between occlusal trauma and periodontal disease requires a truly multidisciplinary approach that combines the expertise of periodontics, orthodontics, functional occlusion, and restorative dentistry. Such an approach should include mechanical control of infection, redirection of occlusal forces, use of protective devices, and, whenever indicated, the application of regenerative strategies based on biomaterials and inflammatory modulation. The functional, aesthetic, and biological rehabilitation of patients will only be fully achieved when it is recognized that occlusal balance and periodontal health are interdependent and inseparable.

References

-

R. D. A. U. Lins, T. S. A. Norões, A. A. de Sousa, A. D. Lemos, and R. D. Alves, “Occurrence of periodontal disease and its relationship with malocclusions,” (in Portuguese), Odontologia Clínico-Científica (Online), Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 165–168, Jul. 2011.

-

T. E. van Dyke and D. Sheilesh, “Risk factors for periodontitis,” Journal of International Academy of Periodontology, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 3–7, 2005.

-

W. W. Hallmon, “Occlusal trauma: effect and impact on the periodontium,” Annals of Periodontology, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 102–107, Dec. 1999, https://doi.org/10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.102

-

D. Tomina et al., “Incidence of malocclusion among young patients with gingival recessions-a cross-sectional observational pilot study,” Medicina, Vol. 57, No. 12, p. 1316, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57121316

-

T. Yucel-Lindberg and T. Båge, “Inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontitis,” Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine, Vol. 15, Aug. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1017/erm.2013.8

-

E. Passanezi and A. C. P. Sant’Ana, “Role of occlusion in periodontal disease,” Periodontology 2000, Vol. 79, No. 1, pp. 129–150, Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12251

-

K. Noguchi and I. Ishikawa, “The roles of cyclooxygenase‐2 and prostaglandin E2 in periodontal disease,” Periodontology 2000, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 85–101, Jan. 2007, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00170.x

-

J. Fan and J. G. Caton, “Occlusal trauma and excessive occlusal forces: Narrative review, case definitions, and diagnostic considerations,” Journal of Periodontology, Vol. 89, No. S1, Jun. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1002/jper.16-0581

-

C. C. Ríos, J. I. Campiño, A. Posada‐López, C. Rodríguez‐Medina, and J. E. Botero, “Occlusal trauma is associated with periodontitis: A retrospective case‐control study,” Journal of Periodontology, Vol. 92, No. 12, pp. 1788–1794, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1002/jper.20-0598

-

F. Meynardi, “The importance of occlusal trauma in the primary etiology of periodontal disease,” Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents, Vol. 32, No. 2 Suppl. 1, pp. 27–34, Jan. 2018.

-

H. Dommisch, C. Walter, J. C. Difloe‐Geisert, A. Gintaute, S. Jepsen, and N. U. Zitzmann, “Efficacy of tooth splinting and occlusal adjustment in patients with periodontitis exhibiting masticatory dysfunction: A systematic review,” Journal of Clinical Periodontology, Vol. 49, No. S24, pp. 149–166, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13563

-

D. Pei, X. Hu, C. Jin, Y. Lu, and S. Liu, “Energy storage and dissipation of human periodontal ligament during mastication movement,” ACS Biomaterials Science and Engineering, Vol. 4, No. 12, pp. 4028–4035, Dec. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.8b00667

-

M. Chen, X. Chen, L. Sun, B. Zhao, and Y. Liu, “Sequential soft – and hard-tissue augmentation after clear aligner-mediated adjustment of traumatic occlusion,” The Journal of the American Dental Association, Vol. 153, No. 6, pp. 572–581.e1, Jun. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2021.11.004

-

S. S. Varghese, “Influence of angles occlusion in periodontal diseases,” Bioinformation, Vol. 16, No. 12, pp. 983–991, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.6026/97320630016983

-

N. Tagger-Green et al., “Radiographic signs of excessive occlusal forces are associated with marginal bone loss: a retrospective clinical study,” Quintessence International, Vol. 54, No. 8, pp. 672–679, Sep. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.b4170135

-

A. Taira, S. Odawara, S. Sugihara, and K. Sasaguri, “Assessment of occlusal function in a patient with an angle class I spaced dental arch with periodontal disease using a brux checker,” Case Reports in Dentistry, Vol. 2018, pp. 1–12, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3876297

-

M. Javali, J. Betsy, R. S. Al Thobaiti, R. Alshahrani, and H. A. Alqahtani, “Relationship between malocclusion and periodontal disease in patients seeking orthodontic treatment in southwestern Saudi Arabia,” Saudi Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 2, p. 133, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_135_19

-

M. Oyama, T. Ukai, Y. Yamashita, and A. Yoshimura, “High‐mobility group box 1 released by traumatic occlusion accelerates bone resorption in the root furcation area in mice,” Journal of Periodontal Research, Vol. 56, No. 1, pp. 186–194, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.12813

-

W. Pan et al., “Traumatic occlusion aggravates bone loss during periodontitis and activates Hippo‐YAP pathway,” Journal of Clinical Periodontology, Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 438–447, Apr. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13065

-

W. Xu et al., “Occlusal trauma inhibits osteoblast differentiation and bone formation through IKK‐NF‐κB signaling,” Journal of Periodontology, Vol. 91, No. 5, pp. 683–692, Oct. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1002/jper.18-0710

-

Q. Lu et al., “Traumatic compressive stress inhibits osteoblast differentiation through long chain non‐coding RNA Dancr,” Journal of Periodontology, Vol. 91, No. 11, pp. 1532–1540, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1002/jper.19-0648

-

S. G. González-Rodríguez, M. Llanes-Rodríguez, and E. Fernández-Pérez, “Orthodontic treatment in an adult patient with controlled chronic periodontitis,” (in Spanish), Revista Habanera de Ciencias Médicas, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 741–751, Oct. 2019.

-

K. T. Martins de Moraes Siqueira et al., “Periodontal disease associated with occlusal trauma,” (in Portuguese), Brazilian Journal of Implantology and Health Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 162–175, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.36557/2674-8169.2023v5n2p162-175

-

N. Dewake, M. Miki, Y. Ishioka, S. Nakamura, A. Taguchi, and N. Yoshinari, “Association between clinical manifestations of occlusal trauma and magnetic resonance imaging findings of periodontal ligament space,” Dentomaxillofacial Radiology, Vol. 52, No. 8, p. 20230, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1259/dmfr.20230176

-

E. S. D. S. Pereira, K. L. Sousa, M. N. Paiva, J. C. S. D. Silva, P. O. Cunha, and T. S. D. Fonseca, “The importance of the interrelationship between periodontics and orthodontics for the prevention of periodontal diseases in orthodontic patients: a literature review,” (in Portuguese), Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento, pp. 33–46, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/odontologia/periodontia-e-a-ortodontia

-

W. Zhong et al., “Expert consensus on orthodontic treatment of patients with periodontal disease,” International Journal of Oral Science, Vol. 17, No. 1, p. 27, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-025-00356-w

-

A. Kumar, “Management of occlusal trauma-related periodontal abscess: A case report,” World Academy of Sciences Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 25–30, 2025.

-

X. Liu et al., “Occlusal trauma aggravates periodontitis through the plasminogen/plasmin system,” Oral Diseases, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 959–969, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.15081

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Anderson Daniel Rodrigues Correa: writing-preparation of the original draft, formal analysis, research. Daniel Henrique da Silva Guimarães: writing-preparation of the original draft, formal analysis, research. Laura Ávila Soares: writing-preparation of the original draft, formal analysis, research. Milena Lopes Oliveira: writing-preparation of the original draft, formal analysis, research. Vitória de Oliveira Moreira: writing-preparation of the original draft, formal analysis, research. Orlando Santiago Junior: supervision, writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The work is a literature review; therefore, no study involving living organisms was conducted.