Abstract

Rolling bearings are key components of rotating machinery such as electric motors, and their health status directly affects the reliability and safety of the equipment. In order to improve the fault classification accuracy of electric motor rolling bearing, this paper proposes a diagnostic method based on CMFSE-SVM. Firstly, the composite multi-scale fuzzy slope entropy (CMFSE) method proposed in this paper is used to extract the characteristics of the vibration signal of the motor rolling bearings. Finally, the obtained feature vectors are sent to the support vector machine (SVM) for fault classification. This paper verifies the classification accuracy of the method proposed in this paper on two publicly available datasets of electric motor rolling bearing faults. The experimental results show that the method proposed in this paper achieves average classification accuracies of 100 % and 99.6 % respectively on all working conditions corresponding to these two datasets. And the classification accuracies were 2.4 % and 2.8 % higher respectively than those of the compared methods.

1. Introduction

In the industrial field, electric motor equipment can be seen everywhere and is widely used. Rolling bearings, as the core components of electric motor equipment, play a crucial supporting role in the smooth operation of the equipment. Relevant statistics show that approximately 40 % of faults in rotating mechanical equipment are caused by rolling bearing failures [1, 2]. Such a high proportion indicates that the fault diagnosis of rolling bearings is extremely important.

Rolling bearing signals belong to non-stationary vibration signals. Extracting their fault characteristics is the key to accurate diagnosis. To better handle nonlinear and non-stationary vibration signals, Reference [3] proposes a complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise (CEEMDAN) method. This method can decompose the original vibration signal into a series of intrinsic mode function components, thereby reducing noise interference and improving the accuracy of fault diagnosis. Reference [4] utilizes multivariable variational mode decomposition (MVMD) to reconstruct signals, which can diagnose rolling bearing faults more comprehensively and accurately. Reference [5] utilizes singular value decomposition (SVD) for signal preprocessing to reduce noise and extract more accurate signal features. References [6-8] extract fault features by converting the original signal from the time domain to the frequency domain. References [9-10] use improved empirical mode decomposition (EMD) to decompose the fault signal into a series of intrinsic mode functions and extract fault features based on these functions. Reference [11] utilizes envelope spectrum analysis combined with Hilbert transform to extract the characteristics of faulty bearings. Convolutional Neural networks (CNNS) perform well in the field of image recognition and therefore have wide applications in the extraction of fault features of rolling bearings. By converting the vibration signal into a time-frequency image, the fault features can be automatically extracted using convolutional neural network [12, 13]. References [14-16] first convert the original fault vibration signal into a two-dimensional image, and then use the CNN to extract the fault features.

In recent years, the pursuit of more reliable and accurate electric motor fault detection technology has been increasing, which has driven electric motors to play a key role in various modern industrial applications. Among numerous emerging methods, entropy-based methods have attracted much attention due to their unique ability to capture the behaviors and anomalies of complex systems based on mathematical algorithms. In reference [17], researchers used the approximate entropy method to extract the fault characteristics of rolling element bearings to achieve quantitative diagnosis of similar spalling faults of rolling element bearings. In the references [18, 19], researchers respectively used fuzzy entropy and sample entropy to extract the fault characteristics of rolling bearings. In reference [20], a composite multi-scale fuzzy entropy method was used to solve the stability and consistency problems of the extracted values in short time series by the multi-scale fuzzy entropy method, and it can effectively extract the fault characteristics of rolling bearings. In reference [21], a composite multi-scale sample entropy method was proposed to solve the problem that the statistical reliability of the multi-scale sample entropy method decreases as the scale factor increases. The effectiveness of this method has been verified in the feature extraction of vibration signals of rolling bearings. To improve the performance of the traditional entropy dispersion method [22], researchers proposed a composite multi-scale fluctuation entropy dispersion method [23] and applied it to extract the fault characteristics of rolling bearings. In reference [24], a permutation entropy method was proposed, which can be used to analyze non-stationary time series signals. In reference [25], a multi-scale permutation entropy method was proposed for extracting the fault characteristics of rolling bearings. Compared with the original permutation entropy method, it can extract the characteristics of signals at different scales by calculating the permutation entropy at different scales. In reference [26], the researchers proposed a fuzzy slope entropy method, which has been proven to have better performance than permutation entropy and slope entropy [27] in analyzing nonlinear complex time series data. The fuzzy logic parameters involved are optimized using a metaheuristic optimization algorithm to achieve better performance [28-29]. These original entropy methods and their improved ones have greatly promoted the research on extracting fault signal features of motor rolling bearings and are conducive to improving the accuracy of fault diagnosis.

At present, there are still some challenges in the diagnosis and classification of motor faults. Although the currently popular CNN method can automatically extract fault features through learning, has strong nonlinear modeling capabilities, is robust to noise and interference, and has excellent fault diagnosis and classification capabilities under big data, the generalization ability of the CNN algorithm under different working conditions is limited. When performing fault diagnosis and classification from the source domain to the target domain, the performance drops significantly. Although the introduction of transfer learning can improve this situation [30], transfer learning still requires a small amount of parameter training to fine-tune the network performance. In addition, the existing deep learning models have a large number of parameters, especially large models often have more than 10 billion parameters [31]. This requires powerful computing resources for deployment, which places strict requirements on hardware overhead and is not conducive to cost savings. The use of entropy methods to extract fault features does not require network parameter training, which saves training time. In addition, it takes up less memory space, which is conducive to reducing application costs. In terms of fault classification algorithms, compared with CNN, SVM does not require a large amount of training and has higher accuracy and stability in the fault classification task of small sample datasets [7, 13, 32-36].

This paper draws inspiration from the above reference and proposes a composite multi-scale fuzzy slope entropy (CMFSE) method to improve the performance of the multi-scale fuzzy slope entropy (MFSE) method in extracting fault features of electric motor rolling bearings. Then, for the extracted sample features, SVM, which has advantages in small sample classification, is used for fault classification.

The chapter arrangement of this article is as follows: The second section is the introduction of the methods used, the third section is the experiments and results, the fourth section is the discussions, the fifth section is the conclusions.

2. Methods

2.1. MFSF and CMFSF

In reference [26], a fuzzy slope entropy (FSE) method was proposed, which can be used to extract signal features in non-stationary time series data. Based on this, this paper proposes a composite multi-scale fuzzy slope entropy (CMFSE) method. This method obtains the coarse-grained time series by compounding the multi-scale time series, and then calculates the entropy value of each obtained coarse-grained sequence. Finally, the entropy value of the obtained coarse-grained time series is averaged as the final characteristic value. This method can better preserve the rich characteristic information contained in the fault signal compared with the multi-scale fuzzy slope entropy (MFSE).

Since the original signal is a digital signal with a certain duration collected by the sensor, before using the entropy method proposed in this paper to extract features, the original signal of each category is first segmented into segments of a fixed length of . The number of segments of the original signal of each category is set to (number of samples), and the data overlap between adjacent segments is . The following are the processing steps of the CMFSE and MFSE methods respectively.

To obtain the MFSE value, the following steps are processed for each segment of the signal:

Step 1: Let the -th segment signal in the sample of category be , and define the coarse-grained sequence for signal by Eq. (1):

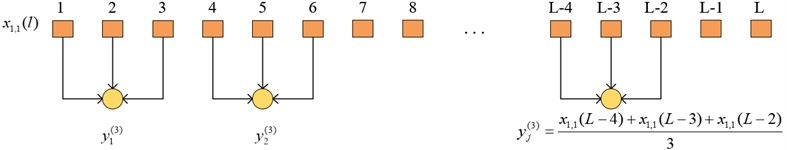

where, represents the coarse-grained sequence under the scale factor (positive integer), and represents the -th point. The above processing procedure can be represented by the following Fig. 1 (taking , , as examples, in the actual situation, , assuming the remainder of is 2).

Fig. 1Schematic diagram of the MFSE coarse-graining sequence process

Step 2: Calculate the FSE value of the coarse-grained sequence under the scale factor , and then the FSE value () of signal under the scale factor can be obtained.

The feature vector composed of the MFSE entropy of signal is expressed by Eq. (2):

To obtain the CMFSE value, the following steps are processed for each segment of the signal:

Step 1: Let the -th segment signal in the sample of category be , and define the coarse-grained sequence for signal by Eq. (3):

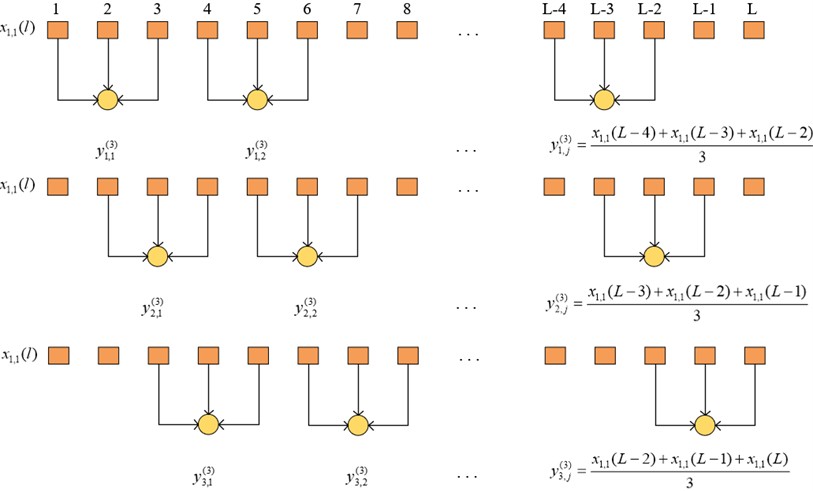

where, represents the -th coarse-grained sequence under the scale factor , and represents the -th point of . The above processing procedure can be represented by the following Fig. 2 (taking , , as examples, in the actual situation, , assuming the remainder of is 2).

Fig. 2Schematic diagram of the coarse-graining sequence process of CMFSE

Step 2: Calculate the FSE value () of each coarse-grained sequence under the scale factor and take the average to obtain the CMFSE value () of signal under the scale factor . The above calculation process is shown as Eq. (4):

The feature vector composed of the CMFSE of signal is expressed by Eq. (5):

2.2. SVM

This paper adopts the Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm. This algorithm is often used in classification tasks. Its essence is to find an optimal hyperplane in the feature space of the data, achieve sample classification through the hyperplane, and allow a certain degree of classification errors at the same time. By introducing a penalty factor to control the degree of punishment for classification errors, in order to solve the problem that the data is not linearly separable in the low-dimensional space, a kernel function is introduced to map the data in the low-dimensional feature space to a higher-dimensional feature space, making the data linearly separable in this high-dimensional space. In this way, linear indivisibility problems that were originally unsolvable in low-dimensional Spaces can be classified in high-dimensional Spaces by finding a suitable hyperplane. The above description can be expressed by the following Eq. (6):

where, represents the weight value of the hyperplane, represents the penalty factor, represents the number of feature vectors in the sample, represents the relaxation variable corresponding to the -th sample, represents the label of the -th sample, represents the feature vector of the -th sample, represents the feature vector after mapping the feature vector of the -th sample to the high-dimensional space, and represents the deviation. The duality problem of Eq. (6) can be expressed by Eq. (7):

where, represents the inner product of the feature vectors of samples and after mapping to a high-dimensional space. The kernel function can be introduced to calculate the result of in Eq. (7). In this paper, the widely used radial basis kernel function is adopted to calculate the result of , as shown in Eq. (8):

where, represents the bandwidth of the radial basis kernel function (). Substituting Eq. (8) into Eq. (7) for solution yields the model corresponding to the division of the hyperplane in the feature space, as shown in Eq. (9):

where, represents the decision function of the model, which is used to classify new samples, and represents the feature vector of the new samples that need to be classified.

3. Results

3.1. Introduction to Experimental software and hardware

The software used in the experiments conducted in this paper is MATLAB R2023b. The program runs on a personal computer, whose CPU model is AMD 5700G, the RAM operating frequency is 4000 MHz, and the memory space size is 32GB.

3.2. Experimental results of the CWRU dataset

The first dataset used in this article is Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) laboratory bearing failure data set, the experiment platform are shown in Fig. 3. This experimental platform is composed of a motor (left), a torque sensor/encoder (middle), and a dynamometer (right). The tested bearing supports the motor shaft. The tested bearings (inner ring, outer ring, and rolling elements) have different fault diameters. The vibration data of the bearings under different rotational speeds and loads are tested by an accelerometer. The data parameters selected for study in this paper are from the bearings at the motor drive end. The sampling rate is 12 KHz and there are four working conditions (0 HP-1797 rmp, 1 HP-1772 rmp, 2 HP-1750 rmp, 3 HP-1730 rmp). This paper selects ten types of data, including normal bearing data, for classification research. Under each working condition, the specific parameters of each category of data sets and samples produced in this paper are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 3CWRU motor bearing experimental platform [37]

![CWRU motor bearing experimental platform [37]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25124/25124-img3.jpg)

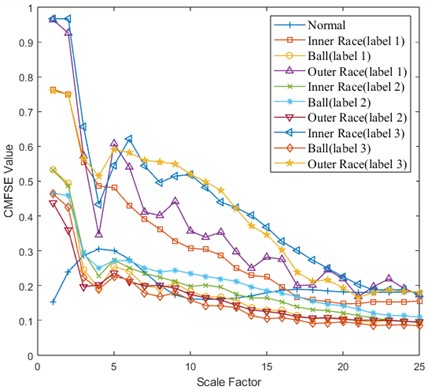

The CMFSE values of each sample in the corresponding dataset in Table 2 are extracted to obtain the feature vector. The following Fig. 4 shows the comparison of CMFSE values of these ten types of faults under different scale factors (taking the first sample of each type of data under the working condition of 0 HP-1797 rmp as an example). It can be seen from Fig. 4 that with the increase of the scale factor value, the CMFSE values corresponding to different types of faults generally show a decreasing trend, the fluctuation range gradually becomes smaller, and the CMFSE values of different types of faults have a certain degree of discrimination, which is conducive to the subsequent SVM classification.

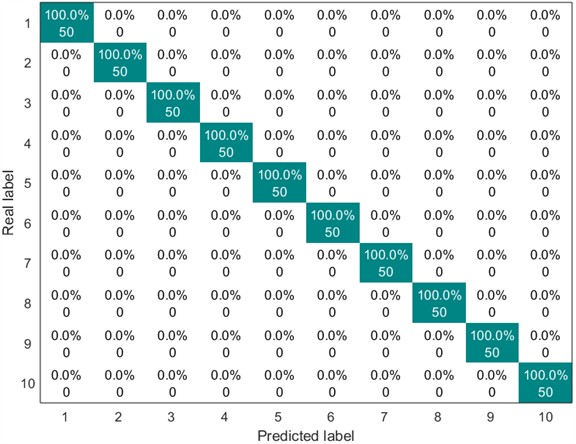

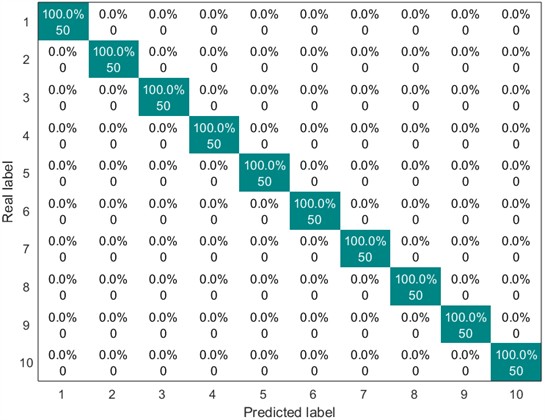

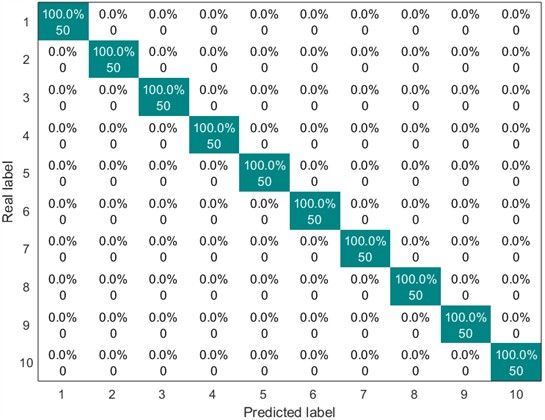

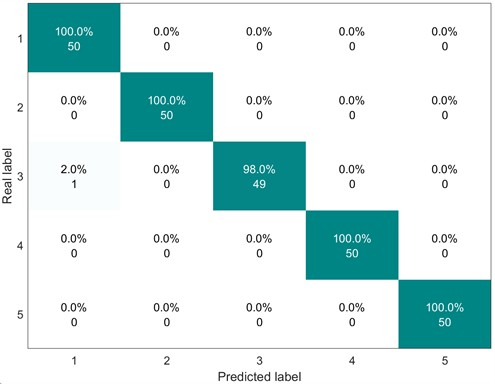

Next, the above ten types of feature vectors are sent into the SVM for classification. The parameter value corresponding to the kernel function is set to 600, and the value of the penalty parameter is set to 2. The division ratio of the training set and the test set is 1:1. The following Figs. 5-8 show the confusion matrix diagrams of the classification results under different working conditions.

Table 1Parameter settings for making the dataset (CWRU)

Parameters | Value |

L | 2048 |

M | 100 |

Q | 1000 |

Table 2Parameter settings for making the dataset (CWRU)

Fault diameter (inch) | Fault location | Label |

0 | Normal | 1 |

0.007 | Inner Race | 2 |

0.007 | Ball | 3 |

0.007 | Outer Race | 4 |

0.014 | Inner Race | 5 |

0.014 | Ball | 6 |

0.014 | Outer Race | 7 |

0.021 | Inner Race | 8 |

0.021 | Ball | 9 |

0.021 | Outer Race | 10 |

Fig. 4CMFSE values of ten types of faults under different scale factors (0 HP-1797 rmp working conditions, the first sample of each type of data)

Fig. 5Confusion matrix of SVM classification results (0 HP-1797 rmp)

Fig. 6Confusion matrix of SVM classification results (1 HP-1772 rmp)

Fig. 7Confusion matrix of SVM classification results (2 HP-1750 rmp)

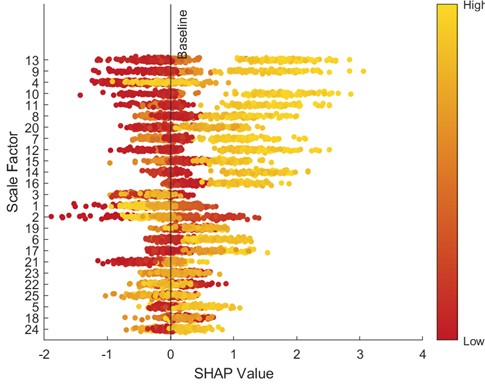

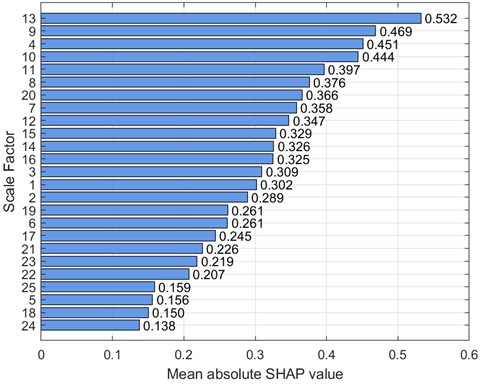

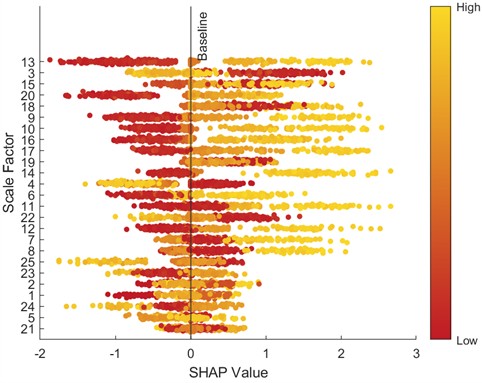

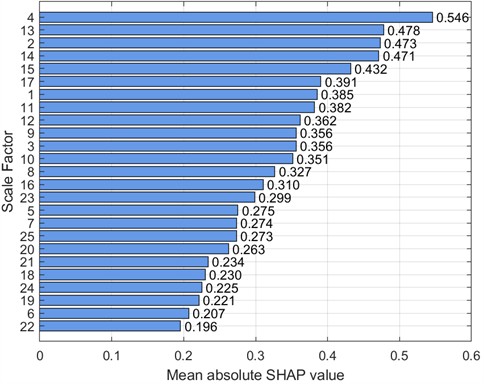

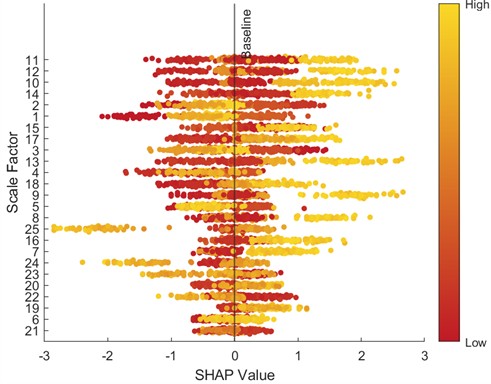

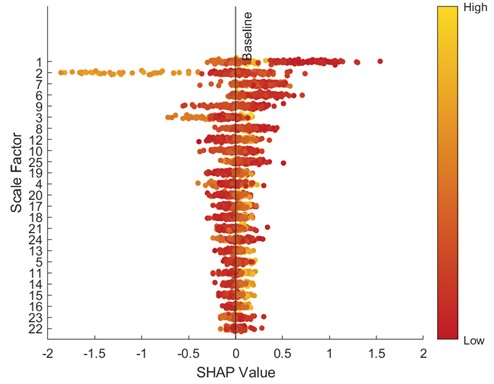

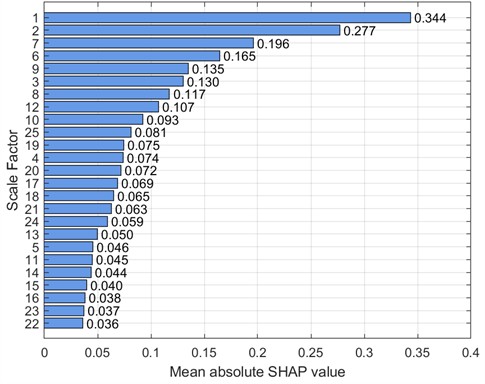

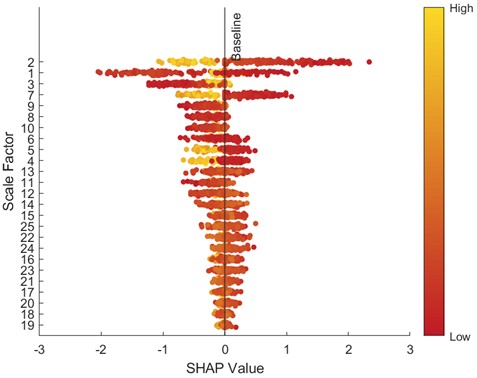

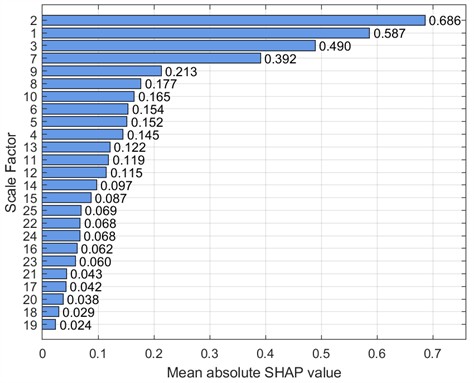

To further analyze feature contributions, the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) tool was introduced to quantify the importance of features at various scales. Specifically, this paper uses SHAP beeswarm plots and SHAP bar charts to visualize features. SHAP beeswarm plots provide a visual representation of the distribution of feature contributions to predictions. The vertical axis of the SHAP beeswarm plot represents features sorted in descending order by their global average SHAP value, with the most important feature at the top. The horizontal axis represents the range of SHAP values, with negative contributions to the left of the baseline (decreasing the predicted value) and positive contributions to the right (increasing the predicted value). A single dot represents the SHAP contribution of a sample to that feature. The color of the dot indicates the actual magnitude of the feature value. SHAP bar charts further quantify the importance of each feature, with importance decreasing from top to bottom, with the top feature having the greatest impact on the model output. Figs. 9-16 show the SHAP beeswarm plots and SHAP bar charts for the first dataset.

Fig. 8Confusion matrix of SVM classification results (3 HP-1730 rmp)

Fig. 9SHAP beeswarm plot (0 HP-1797 rmp)

In order to prove the superiority of this method, this paper compares the classification accuracy, memory usage, and running time by changing different entropy methods. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3Comparison of fault classification accuracy under different working conditions (CWRU)

Working condition | Entropy method | Average classification accuracy (%) | Memory usage (MB) | Run time (S) |

0 HP-1797 rmp | CMFSE | 100 | 29.9 | 137.9. |

MFSE | 94.2 | 28.2 | 31.2 | |

1 HP-1772 rmp | CMFSE | 100 | 29.7 | 138.2. |

MFSE | 96.4 | 27.8 | 30.8 | |

2 HP-1750 rmp | CMFSE | 100 | 30.1 | 137.5. |

MFSE | 99.8 | 28..2 | 31.7 | |

3 HP-1730 rmp | CMFSE | 100 | 29.5 | 138.9. |

MFSE | 100 | 28.4 | 31.5 |

Fig. 10SHAP bar chart (0 HP-1797 rmp)

Fig. 11SHAP beeswarm plot (1 HP-1772 rmp)

Fig. 12SHAP bar chart (1 HP-1772 rmp)

Fig. 13SHAP beeswarm plot (2 HP-1750 rmp)

Fig. 14SHAP bar chart (2 HP-1750 rmp)

Fig. 15SHAP beeswarm plot (3 HP-1730 rmp)

Fig. 16SHAP bar chart (3 HP-1730 rmp)

3.3. Experimental results of the SU dataset

In order to further verify the performance of the proposed method, this paper uses another dataset from Southeast University (SU) in China for verification. The experimental platform is shown in Fig. 17.

Fig. 17Electric motor experimental platform of southeast university [38]

![Electric motor experimental platform of southeast university [38]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25124/25124-img17.jpg)

The dataset consists of a gearbox fault dataset and a bearing fault dataset. This paper uses a bearing fault dataset, which contains two working conditions (20 Hz-0 V, 30 Hz-2 V). Each working condition contains five types of data including normal bearings. These raw data are collected by vibration sensors installed on the experimental platform. The specific parameters of each fault category sample under each working condition are shown in Table 4. The other parameter settings of this dataset are the same as those of the previous dataset, and will not be repeated in this article.

Table 4Fault sample parameter (SU)

Fault location | Label |

Health working state | 1 |

Inner ring | 2 |

Ball | 3 |

Outer ring | 4 |

Combination fault (both inner ring and outer ring) | 5 |

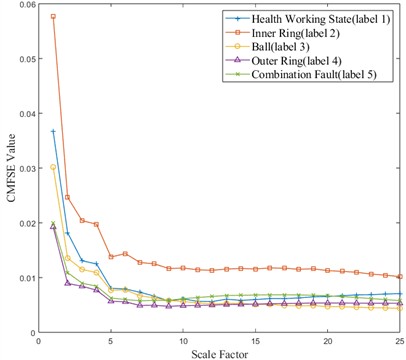

After each sample data is reconstructed, the CMFSE value is extracted to obtain the feature vector. Fig. 18 shows the comparison of CMFSE values of these five types of faults under different scale factors (taking the first sample of each type of data under the working condition of 20 Hz-0 V as an example). It can be seen from Fig. 18 that with the increase of the scale factor value, the CMFSE values corresponding to different types of faults generally show a decreasing trend, the fluctuation range gradually becomes smaller, and the CMFSE values of different types of faults have a certain degree of discrimination, which is conducive to the subsequent SVM classification.

Fig. 18CMFSE values of five types of faults under different scale factors (20 Hz-0 V working condition, the first sample of each type of data)

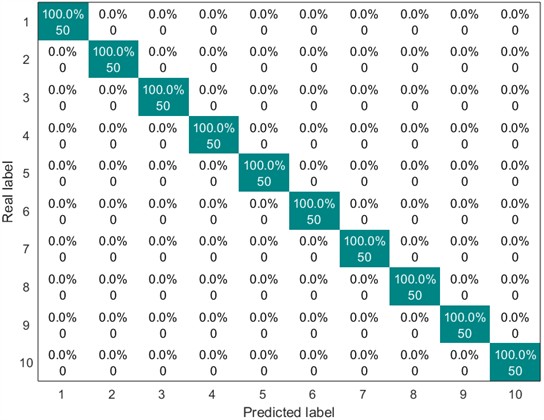

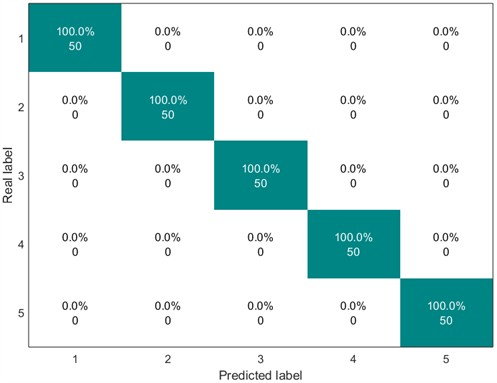

Next, the feature vectors composed of the above five types of faults are sent into the SVM for classification. The following Fig. 19 and Fig. 20 show the classification result graphs under different working conditions.

Fig. 19Confusion matrix of SVM classification results (20 Hz-0 V)

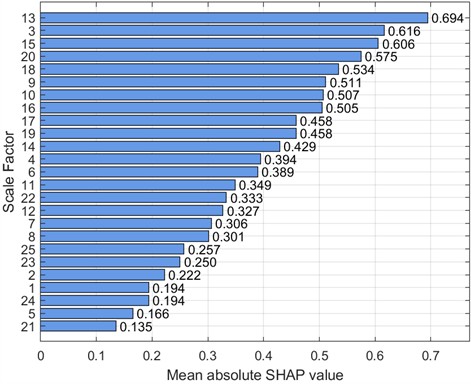

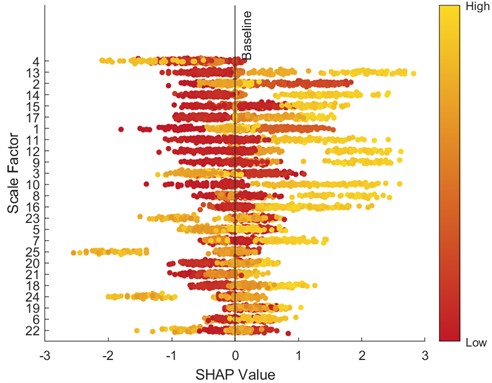

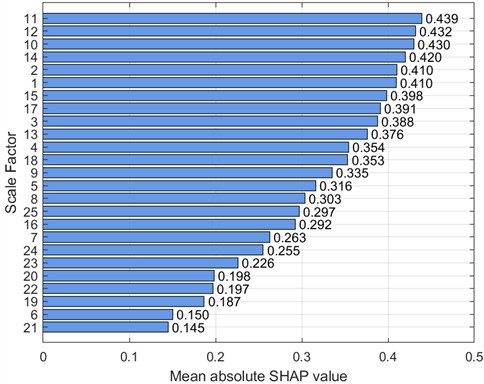

The following Figs. 21 to 24 are the corresponding SHAP beeswarm plots and SHAP bar charts.

Fig. 20Confusion matrix of SVM classification results (30 Hz-2 V)

Fig. 21SHAP beeswarm plot (20 Hz-0 V)

Fig. 22SHAP bar chart (20 Hz-0 V)

Fig. 23SHAP beeswarm plot (30 Hz-2 V)

Fig. 24SHAP bar chart (30 Hz-2 V)

Table 5 compares the classification accuracy, space occupied, and running time of two different entropy methods.

Table 5Comparison of fault classification accuracy under different working conditions (SU)

Working condition | Entropy method | Average classification accuracy (%) | Memory usage (MB) | Run time (S) |

20 Hz-0 V | CMFSE | 99.6 | 12.5 | 68.8 |

MFSE | 98. | 11.6 | 15.4 | |

30 Hz-2 V | CMFSE | 100 | 12.9 | 69.1 |

MFSE | 96 | 11.8 | 15.2 |

4. Discussions

It can be known from Figs. 5 to 8 that the classification accuracy of the CMFSE method under the four working conditions in the first dataset is 100 %. However, the classification accuracy of the MFSE method is 100 % only under the fourth working condition, and the classification accuracy is lower than 100 % under other working conditions. The average accuracy of the MFSE method under all working conditions is 97.6 %, and the CMFSE method is 2.4 % higher than the MFSE method. This result proves the superiority of the method proposed in this paper.

It can be known from Figs. 19 to 20 that the average classification accuracy of the CMFSE method under the two working conditions in the second dataset is 99.8 %, while the average classification accuracy of the MFSE method under the two working conditions in the second dataset is 97 %. The CMFSE method is 2.8 % higher than the MFSE method. This further proves the superiority of the method proposed in this paper.

In terms of algorithm complexity, in terms of space complexity, it can be seen from Table 3 that the CMFSE method occupies an average memory space of 29.8 MB, and the MFSE method occupies an average memory space of 28.2 MB, and the difference between the two is not large. In terms of time complexity, it can be seen from Table 3 that for feature extraction and classification of 1000 samples, the CMFSE method has an average running time of 138.1 S in four working conditions, and an average time of about 0.14 S per sample. The MFSE method has an average running time of 31.3 S in four working conditions, and an average time of about 0.03 S per sample. The MFSE method takes less time. Table 5 shows that for feature extraction and classification of 500 samples, the CMFSE method uses an average memory footprint of 12.7 MB, while the MFSE method uses an average memory footprint of 11.7 MB, a significant difference between the two methods. Table 5 also shows that the CMFSE method has an average runtime of 68.9 S in both conditions, with an average runtime of approximately 0.14 S per sample. The MFSE method has an average runtime of 15.3 S in both conditions, with an average runtime of approximately 0.03 S per sample, resulting in a shorter runtime. Overall, the CMFSE method has a higher complexity than the MFSE method, but its classification accuracy is superior. Considering the similar memory footprint between the two methods, the CMFSE method takes less than 0.2 S to diagnose a single sample, which still demonstrates good real-time performance in practical applications.

Furthermore, this paper only requires half of the samples in the dataset to participate in the training, and a very high classification accuracy can be achieved on the test set, indicating that the method proposed in this paper has a strong feature extraction ability. However, there is still room for further optimization of the method proposed in this paper. For example, we can study the influence of the sample data length of the dataset and the number of features in the feature vector on the fault diagnosis accuracy, so as to find a balance between the algorithm complexity and the diagnosis and classification accuracy. We can also further study the combination of the proposed method and convolutional neural network for fault classification.

5. Conclusions

The composite multi-scale fuzzy slope entropy method proposed in this paper does not need to decompose the original signal before extracting the rolling bearing fault features, but directly extracts the entropy value of the original signal, which is conducive to reducing the complexity of the algorithm. At the same time, the method proposed in this paper has been verified on two public data sets and has the advantage of high classification accuracy. Compared with the multi-scale fuzzy slope entropy, this method has better fault classification performance and can be used in the field of motor rolling bearing fault diagnosis, which has certain practical application value.

References

-

M. Alonso-González, V. G. Díaz, B. L. Pérez, B. C. P. G.-Bustelo, and J. P. Anzola, “Bearing fault diagnosis with envelope analysis and machine learning approaches using CWRU dataset,” IEEE Access, Vol. 11, pp. 57796–57805, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2023.3283466

-

Z. Ke, C. Di, and X. Bao, “Adaptive suppression of mode mixing in CEEMD based on genetic algorithm for motor bearing fault diagnosis,” IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, Vol. 58, No. 2, pp. 1–6, Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/tmag.2021.3082138

-

L. Shi, W. Liu, D. You, and S. Yang, “Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on CEEMDAN and CNN-SVM,” Applied Sciences, Vol. 14, No. 13, p. 5847, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135847

-

M. Mao et al., “Fault diagnosis method using MVMD signal reconstruction and MMDE-GNDO feature extraction and MPA-SVM,” Frontiers in Physics, Vol. 12, p. 13010, Feb. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2024.1301035

-

K. Li, H. Wu, and Y. Han, “High-low frequency features fusion and integrated classification SCNs for intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearing,” International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 1889–1926, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-024-02369-z

-

Z. Zhang and L. Wu, “Graph neural network-based bearing fault diagnosis using granger causality test,” Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 242, p. 122827, May 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122827

-

C. He, T. Wu, R. Gu, and H. Qu, “Bearing fault diagnosis based on wavelet packet energy spectrum and SVM,” in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 1684, No. 1, p. 012135, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1684/1/012135

-

Z. Guo, M. Yang, and X. Huang, “Bearing fault diagnosis based on speed signal and CNN model,” Energy Reports, Vol. 8, pp. 904–913, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2022.08.041

-

Y. F. Hu and Q. Li, “An adjustable envelope based EMD method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis,” in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 1043, No. 3, p. 032017, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/1043/3/032017

-

Y. Li, J. Zhou, H. Li, G. Meng, and J. Bian, “A fast and adaptive empirical mode decomposition method and its application in rolling bearing fault diagnosis,” IEEE Sensors Journal, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 567–576, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2022.3223980

-

Lei Guo, Jin Chen, and Xinglin Li, “Rolling bearing fault classification based on envelope spectrum and support vector machine,” Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 15, No. 9, pp. 1349–1363, Jul. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546308095224

-

Y. Lai, J. Chen, G. Wang, Z. Wang, and P. Miao, “Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on continuous wavelet transform and transfer convolutional neural network,” in International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering, p. 82, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2615182

-

B. Song, Y. Liu, P. Lu, and X. Bai, “Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on time-frequency transform-assisted CNN: a comparison study,” in IEEE 12th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference (DDCLS), pp. 1273–1279, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/ddcls58216.2023.10166631

-

Z. Zhou, Q. Ai, P. Lou, J. Hu, and J. Yan, “A novel method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on Gramian angular field and CNN-ViT,” Sensors, Vol. 24, No. 12, p. 3967, Jun. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24123967

-

Q. Zhang and Z. Ju, “Rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on 2D CNN and hybrid kernel fuzzy SVM,” Advanced Theory and Simulations, Vol. 8, No. 6, p. 24007, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1002/adts.202400793

-

H. Wang, J. Xu, R. Yan, C. Sun, and X. Chen, “Intelligent bearing fault diagnosis using multi-head attention-based CNN,” Procedia Manufacturing, Vol. 49, pp. 112–118, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2020.07.005

-

S. Zhao, L. Liang, G. Xu, J. Wang, and W. Zhang, “Quantitative diagnosis of a spall-like fault of a rolling element bearing by empirical mode decomposition and the approximate entropy method,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 154–177, Oct. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2013.04.006

-

J. Zheng, J. Cheng, and Y. Yang, “A rolling bearing fault diagnosis approach based on LCD and fuzzy entropy,” Mechanism and Machine Theory, Vol. 70, pp. 441–453, Dec. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2013.08.014

-

D. Zhuang et al., “The IBA-ISMO method for rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on VMD-sample entropy,” Sensors, Vol. 23, No. 2, p. 991, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23020991

-

J. Zheng, H. Pan, and J. Cheng, “Rolling bearing fault detection and diagnosis based on composite multiscale fuzzy entropy and ensemble support vector machines,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 85, pp. 746–759, Feb. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2016.09.010

-

S.-D. Wu, C.-W. Wu, S.-G. Lin, K.-Y. Lee, and C.-K. Peng, “Analysis of complex time series using refined composite multiscale entropy,” Physics Letters A, Vol. 378, No. 20, pp. 1369–1374, Apr. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2014.03.034

-

M. Rostaghi and H. Azami, “Dispersion entropy: a measure for time-series analysis,” IEEE Signal Processing Letters, Vol. 23, No. 5, pp. 610–614, May 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/lsp.2016.2542881

-

X. Gan, H. Lu, and G. Yang, “Fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings based on composite multiscale fluctuation dispersion entropy,” Entropy, Vol. 21, No. 3, p. 290, Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/e21030290

-

C. Bandt and B. Pompe, “Permutation entropy: a natural complexity measure for time series,” Physical Review Letters, Vol. 88, No. 17, p. 17410, Apr. 2002, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.88.174102

-

M. N. Yasir and B.-H. Koh, “Data decomposition techniques with multi-scale permutation entropy calculations for bearing fault diagnosis,” Sensors, Vol. 18, No. 4, p. 1278, Apr. 2018, https://doi.org/10.3390/s18041278

-

Y. Li, G. Tian, Y. Cao, Y. Yi, and D. Zhou, “Optimized fuzzy slope entropy: a complexity measure for nonlinear time series,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, Vol. 73, pp. 1–14, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/tim.2024.3493878

-

D. Cuesta-Frau, “Slope entropy: a new time series complexity estimator based on both symbolic patterns and amplitude information,” Entropy, Vol. 21, No. 12, p. 1167, Nov. 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/e21121167

-

H. R. Patel, “Metaheuristic optimization algorithm for optimal design of type-2 fuzzy controller,” International Journal of Applied Evolutionary Computation, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 1–15, Dec. 2022, https://doi.org/10.4018/ijaec.315637

-

H. R. Patel, “Optimal intelligent fuzzy TID controller for an uncertain level process with actuator and system faults: Population-based metaheuristic approach,” Franklin Open, Vol. 4, p. 100038, Sep. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fraope.2023.100038

-

I. Misbah, C. K. M. Lee, and K. L. Keung, “Fault diagnosis in rotating machines based on transfer learning: Literature review,” Knowledge-Based Systems, Vol. 283, p. 111158, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111158

-

X. Tu, Z. He, Y. Huang, Z.-H. Zhang, M. Yang, and J. Zhao, “An overview of large AI models and their applications,” Visual Intelligence, Vol. 2, No. 1, p. 34, Dec. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s44267-024-00065-8

-

B. Wang, W. Qiu, X. Hu, and W. Wang, “A rolling bearing fault diagnosis technique based on recurrence quantification analysis and Bayesian optimization SVM,” Applied Soft Computing, Vol. 156, p. 111506, May 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111506

-

X. Wang, R. Meng, G. Wang, X. Liu, X. Liu, and D. Lu, “The research on fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on current signal CNN-SVM,” Measurement Science and Technology, Vol. 34, No. 12, p. 125021, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/acefed

-

S. M. Yadavar Nikravesh, H. Rezaie, M. Kilpatrik, and H. Taheri, “Intelligent fault diagnosis of bearings based on energy levels in frequency bands using wavelet and support vector machines (SVM),” Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, Vol. 3, No. 1, p. 11, Jan. 2019, https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp3010011

-

H. Zhang, S. Li, and Y. Cao, “A TFG-CNN fault diagnosis method for rolling bearing,” Mechanisms and Machine Science, pp. 237–249, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99075-6_21

-

C. Li, X. Yin, J. Chen, H. Yang, and L. Hong, “Bearing fault diagnosis based on wavelet transform and convolutional neural network,” OALib, Vol. 9, No. 6, pp. 1–14, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1108845

-

X. Dai, K. Yi, F. Wang, C. Cai, and W. Tang, “Bearing fault diagnosis based on POA-VMD with GADF-Swin Transformer transfer learning network,” Measurement, Vol. 238, p. 115328, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115328

-

S. Shao, S. Mcaleer, R. Yan, and P. Baldi, “Highly accurate machine fault diagnosis using deep transfer learning,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 2446–2455, Apr. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/tii.2018.2864759

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Linlin Chen: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, validation, investigation, resources, software, visualization, writing-original draft preparation. Celso Co: writing-review and editing, supervision.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.