Abstract

Railway embankments are key elements of transport infrastructure whose stability depends on soil, hydrogeological, and climatic factors. Wind and rainfall erosion threaten slope integrity, causing soil loss and potential landslides. This study integrates field experiments and modeling to assess erosion mechanisms and the effectiveness of geosynthetic geomats for slope protection. Tests on the Bukhara-Miskin railway section determined wind and rainfall thresholds for soil displacement and evaluated geomat performance by slope stability, vegetation density, and runoff resistance. Reinforced slopes showed almost no soil washout, with vegetation density of 4000-5500 kg/ha – over 200 % higher than traditional seeding. Geomat use reduced erosion by up to 80 % and improved ecological resilience, offering a reliable, cost-effective, and sustainable solution for long-term railway slope stability.

Highlights

- Modes of soil particle movement

- Slope leveling process

- Geomat placement process

- Research site and slope condition (April 2025), Qorlitog‘–Kiyikli Section

1. Introduction

Erosion of railway embankments critically affects transport infrastructure reliability [1]. Russian studies showed that erosion reduces the bearing capacity of the earth bed and increases maintenance costs [2], while Ramazanov linked desertification to accelerated soil degradation [3]. Uzbekistan’s environmental review identified erosion as a major challenge impacting infrastructure [4]. Research confirmed the strong influence of water erosion on soil stability [5] and wind erosion mechanisms established by Chepil and Woodruff form the basis of modern control methods [6]. In India, practical guidelines for erosion and drainage protection of railway formations were developed [7-9]. Vegetation-based slope protection has been studied since the 1960s and remains essential for comprehensive stabilization [10-12].

Recent progress in geosynthetics includes Medvedev’s practical approaches [6] and Zhukovets’s analytical methods for slope assessment [12]. Uzbek studies highlighted the need for targeted protection in transition zones and bridge approaches [13, 14], and examined subgrade behavior under dynamic and train loads [15-18]. Despite these advances, effective adaptation of erosion control to Central Asia’s arid climate – with strong winds, poor vegetation, and intense precipitation – remains insufficient.

The aim of this study is to develop and validate effective erosion control systems for railway embankments using geosynthetic materials in the natural conditions of Uzbekistan.

The objectives are:

– To analyze climatic and geological factors influencing erosion in the Bukhara–Miskin railway section.

– To identify wind and water-induced erosion mechanisms.

– To evaluate the performance of geosynthetics in field trials.

– To compare innovative materials with conventional stabilization technologies.

– To provide engineering recommendations for erosion control in arid regions.

2. Materials and methods

Experiments show that soil particle displacement by wind occurs only above a threshold velocity. For particles 0.10-0.15 mm in diameter, erosion starts at wind speeds of 12-15 km/h measured 150 mm above the ground [7].

According to the classification developed by Chepil and Woodruff [6], soil particles are categorized by diameter and their susceptibility to wind erosion as follows:

Table 1Relationship between soil particle size and wind erosion mechanisms

No. | Particle diameter (mm) | Susceptibility to wind erosion |

1 | < 0.42 | Highly erodible |

2 | 0.42-0.84 | Moderately erodible |

3 | 0.84-6.4 | Generally non-erodible |

4 | > 6.4 | Non-erodible |

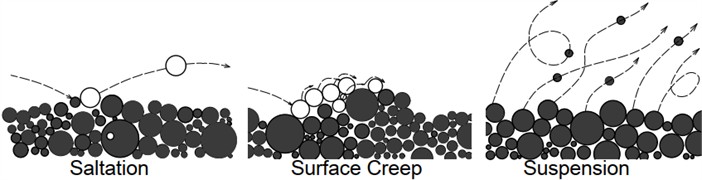

Soil particle movement under wind action occurs via three mechanisms [7]:

Saltation – bouncing of 0.05-0.5 mm particles within 5-30 cm above the surface, where impacts dislodge additional grains.

Creep – rolling or sliding of larger particles (0.5-1 mm) along the ground, triggered by saltating impacts.

Suspension – uplift of fine particles (< 0.1 mm) into the airflow, enabling long-distance transport through the atmosphere (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1Modes of soil particle movement

These three processes (saltation, creep, and suspension) operate simultaneously and collectively determine the overall extent of soil erosion. The relative dominance of each process depends on the soil composition, moisture content, and wind conditions [7].

3. Geomat installation technology

In November 2024, an experimental study was conducted by Uzbekistan Railways on the Bukhara-Miskin railway section-located in a sandy zone–specifically at kilometer point PK 41403+04 near the Qorlitog‘-Kiyikli segment under PCh-16. The objective was to protect the railway track from wind and sand impact and to reduce slope erosion [19], [20].

Based on the recommendations from sources [21], [22], the installation process of erosion-control geomats on the railway embankment slopes followed these step-by-step procedures:

Surface preparation: slopes were leveled and cleared of debris, large rocks, and vegetation [23]. A 300 mm deep anchor trench was dug 300 mm from the embankment edge to prevent geomat displacement. Geomats were laid across the designated area and anchored along the trench. Anchors were selected according to local soil density – ranging from 6-10 mm in diameter and 300-700 mm in length. Geomat segments were overlapped (150 mm vertical and 200 mm horizontal) and fastened with anchors at 500-1000 mm intervals [24], [25]. The anchor trench was filled. Two-thirds of the vegetation seeds were sown at a rate of 40-60 g/m2 [26], [27]. A topsoil layer of 50-100 mm was applied. The remaining one-third of the seeds was broadcast over the surface. Surface compaction was done using hand tampers or compactors weighing 20-30 kg to ensure uniform contact (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2Installation of Geomats on the Slope at Qorlitog’-Kiyikli Section. Photos were taken by the article’s author A. Sh. Uralov during field research on the Bukhara-Miskin railway line (Qorlitog’-Kiyikli section) in November 2024

a) Initial condition of the slope

b) Slope leveling process

c) Excavation of anchor trench

d) Sowing 2/3 of the vegetation seeds

e) Geomat placement process

f) Anchoring with steel pins

g) Sowing the remaining 1/3 of vegetation seeds

h) Covering the surface with soil

4. Modeling and analysis

Assessment of erosion risk using the RUSLE model. Annual soil loss is determined by the following formula RUSLE (Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation) [28]:

where – annual soil loss, t/ha·year; – precipitation erosion activity index (mm·MJ/ha·year); – coefficient of soil susceptibility to erosion; – topographic factor, taking into account the influence of slope length and angle; – coefficient reflecting the influence of the coating type; – coefficient expressing the effectiveness of preventive measures.

Influence. As slope angle () and length () increase, increases, and so does :

Increasing the intensity and duration of precipitation increases the value and activates the stages of erosion.

Consideration of geomatic and vegetation impact through coefficients. As a result of field studies, it was established that in the presence of geomatic cover and vegetation, the cover () and prophylactic () coefficients decrease:

Accordingly, the annual loss in protected condition is calculated as follows:

This means that with a combination of geomat-vegetation, the erosion rate decreases to 40-60 %.

As the angle of inclination increases, the effectiveness of protection increases:

Influence of hydraulic stability (Schilds criterion) and hole structure. The hole size of the geomat is am ≈ 25-55 mm, which breaks down the flow energy into small segments and reduces the local cutting force. As a result, the critical shear force required for particle displacement increases:

where – cutting force required for particle displacement, Pa; – Shields parameter (0.03-0.06); – soil particle density, kg/m3; – liquid density, kg/m3; – acceleration of gravity (9.81 m/s2); – characteristic particle diameter, m.

Covered with geomat:

With increasing root density (), the critical cutting force increases further:

This means that vegetation and geomat together ensure hydraulic stability and reduce the tendency of the soil to displacement.

5. Results and discussion

In April 2025, field observations were carried out at the research site located at kilometer point PK 41403+04 on the Qorlitog‘-Kiyikli section under the jurisdiction of Qorlitog‘ railway maintenance area (PCh-16). According to the analysis, the area where the geomats were installed showed virtually no signs of damage. The integrity of the geomat layer remained intact throughout the period of observation. Moreover, a significant growth of native desert vegetation was recorded at the site (Fig. 3).

As a result of the RUSLE model, with a combination of geomat + vegetation, the and coefficients decreased to 40-60 %. According to the Shields criterion, the cutting force required for particle displacement increased (Table 2).

Fig. 3Research Site and Slope Condition (April 2025), Qorlitog‘–Kiyikli Section. Photos were taken by the article’s author A. Sh. Uralov during field research on the Bukhara-Miskin railway line (Qorlitog‘-Kiyikli section) in April 2025

Table 2Diameter and kinetic energy of a raindrop

No. | Rain intensity (mm/h) | Droplet diameter (mm) | Kinetic energy (J/m2/h) |

1 | Drizzle < 1 | 0,9 | 2 |

2 | Light 1 | 1,2 | 10 |

3 | Moderate 4 | 1,6 | 50 |

4 | Heavy 15 | 2,1 | 350 |

5 | Excessive 40 | 2,4 | 1000 |

6 | Cloud burst 100 | 2,9 | 3000 |

7 | Cloud burst 100 | 4,0 | 4000 |

8 | Cloud burst 100 | 6,0 | 4500 |

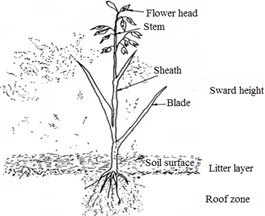

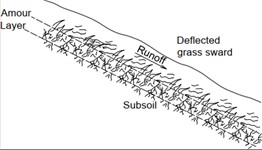

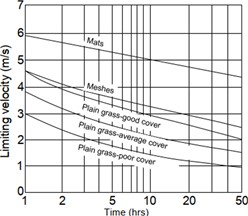

The obtained results are consistent with international studies [7]. Geosynthetic materials divide water and wind energy into small segments, reduce runoff, and reduce the risk of erosion. In the network of geomatons, the root system develops and natural reinforcement is formed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4Vegetation cover structure, protective layers, and flow velocity limits

a) Components of the seedling plant

b) Plant-supplied (protective layer)

c) Boundary velocities of ordinary and reinforced grass

Such bioengineering approaches are effective not only from an ecological, but also from an economic point of view. Compared to concrete or stone pavement, the cost is reduced by 25-40 %, but the service life is more than 10 years.

6. Conclusions

Practical studies on the Qorlitog’-Kiyikli section (Bukhara-Miskin line) confirmed that geosynthetic materials, particularly geomats with vegetation cover, provide the most effective protection of railway slopes from erosion.

Field experiments showed that erosion intensity depends on rainfall, slope angle, and soil density. Geomat installation significantly reduced these effects, limiting soil erosion and particle migration. The geomat structure dissipates flow energy, while plant roots integrate the soil layer and enhance its mechanical stability.

Comparative tests revealed a 40-60 % reduction in soil loss and particle movement on geomat-covered slopes. The results also showed that erosion resistance is strongly influenced by root density and geomat mesh size.

The combined use of geomats and vegetation cover increased hydraulic and aeolian stability, improved moisture retention, and ensured long-term soil integrity. The findings confirm that geosynthetic technologies are highly effective for anti-erosion protection in arid, windy regions with steep slopes, extending the service life of railway tracks.

References

-

K. Lesov, A. Abdujabarov, M. Kenjaliyev, and O. Mirzakhidova, “Techno-economic evaluation of geotextile application as a separation layer and its contribution,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 583, p. 01008, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202458301008

-

M. S. Kuznetsov and G. P. Glazunov, Erosion and Soil Protection: Textbook. (in Russian), Moscow, Russia: Moscow State University Publishing House, 2005.

-

B. R. Ramazanov, “Erosion processes, desertification in nature and their main characteristics,” (in Russian), Academic research in educational sciences, Vol. 2, No. 5, pp. 386–396, Jan. 2021.

-

“Environmental Performance Review of Uzbekistan,” United Nations, New York and Geneva, 2010.

-

N. Sh. Rashidov, “Water erosion and its effect on crop yields,” Educational Research in Universal Sciences, Vol. 2, No. 10, pp. 386–388, 2023.

-

W. S. Chepil and N. P. Woodruff, “The physics of wind erosion and its control,” Advances in Agronomy, Vol. 15, pp. 211–302, Jan. 1963, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2113(08)60400-9

-

“Guidelines on erosion control and drainage of railway formation (Guideline No. GE: G-4),” Geo-technical Engineering Directorate, Research Designs and Standards Organisation, Lucknow, India, Feb. 2005.

-

I. Chizhikov and Z. Fazilova, “Geocomposites on the basis of geomeshes for road and bridge construction,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 457, p. 01006, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202345701006

-

“Recommendations on the choice of anti-erosion measures,” (in Russian), MIAKOM, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2015.

-

V. I. Gritsyn and B. I. Tsvelodub, “Mechanized strengthening of earth bed using grass seeding,” (in Russian), Transport Publishing House, Moscow, Russia, 1968.

-

E. S. Ashpiz, A. I. Gasanov, and B. E. Glyuzberg, “Railway track: textbook,” (in Russian), FGBOU Educational and Methodological Center for Education in Railway Transport, Moscow, Russia, 2013.

-

A. G. Zhukovets, “Calculation of the stability of the earth bed and its protection from erosion: educational and methodical manual,” (in Russian), BelGUT, Belgorod, Russia, 2009.

-

M. Mekhmonov, S. Makhamadjonov, and A. Uralov, “Efficiency of reinforcement of transition sections on the railroad by the developed constructions,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 508, p. 08017, Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202450808017

-

K. S. Lesov, M. M. Rasulmukhamedov, A. K. Mavlanov, and M. K. Kenjaliyev, “Tension of ground pressure on the foundations of railway catenary supports,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 401, p. 03035, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202340103035

-

A. Abdujabarov, P. Begmatov, F. Eshonov, M. Mekhmonov, and M. Khamidov, “Influence of the train load on the stability of the subgrade at the speed of movement,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 264, p. 02019, Jun. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202126402019

-

N. Begmatov, U. Ergashev, K. Lesov, and S. Shayakhmetov, “Bearing capacity of the subgrade for high-speed train traffic,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 531, p. 02006, Jun. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202453102006

-

A. A. Glagolyev, “Development of comprehensive protection of the roadbed from waterlogging by atmospheric wastewater,” (in Russian), Voronezh, Russia, 2007.

-

O. V. Petrov, “Wind erosion and wind-erosion research,” (in Russian) in Atmospheric and Oceanographic Sciences Library, Vol. 1, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2025, pp. 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8895-7_1

-

K. S. Lesov and A. S. O. ‘Ralov, “Protect the slopes of the land polo,” (in Uzbek), in Proceedings of the International Scientific and Technical Conference on Sustainable Architecture and City Planning in the Aral Sea Region, 2024.

-

K. Lesov, A. O. ’Ralov, M. Kenjaliyev, N. Begmatov, and U.B. Ergashev, “Calculation of slope stability against erosion deformations,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 583, p. 01006, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202458301006

-

“Program and Methods of experimental research on strengthening the slopes of railway earth beds,” (in Uzbek), JSC Uzbekistan Railways, Tashkent Institute of Railway Engineers, Scientific Research Laboratory Track and Track Facilities, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2019.

-

U. Ergashev and N. Begmatov, “Ensuring safety of track-laying works while long-welded rails replacement,” Discover Applied Sciences, Vol. 7, No. 5, p. 470, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-025-07049-3

-

K. S. Lesov, A. S. O.‘Ralov, and J. B. Yuldashaliyev, “Analysis of erosion processes and use of geosynthetic materials,” (in Uzbek), Problems of Architecture and Construction, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 40–47, Mar. 2025, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15239323

-

D. A. Makhmudova and F. K. Ikramova, “Strengthening of the earth bed using innovative materials based on basalt,” (in Russian), Universum: Technical Sciences, Vol. 12, No. 81, 2020.

-

“Methodological recommendations for choosing the design of slope reinforcement of the earth bed of public roads,” (in Russian), Moscow, Russia, ODM 218.2.078-2016, 2016.

-

P. Malinin, “Slope reinforcement,” (in Russian) in Dictionary Geotechnical Engineering/Wörterbuch GeoTechnik, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014, pp. 1250–1250, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-41714-6_194497

-

T. Y. Zhukova, A. V. Eremeev, N. V. Khanov, M. I. Zborovskaya, and A. I. Novichenko, “Study on the application possibility of engineering-ecological anti-erosion cover – geomat with soil and grass seeding,” (in Russian), Construction Economics, No. 11, 2022.

-

S. A. Matveev, “Innovative materials, technologies and constructions: theory and practice of application,” (in Russian), Construction Equipment and Technologies. Geosynthetic Materials, special ed., No. 2(2), Nov. 2015.

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.