Abstract

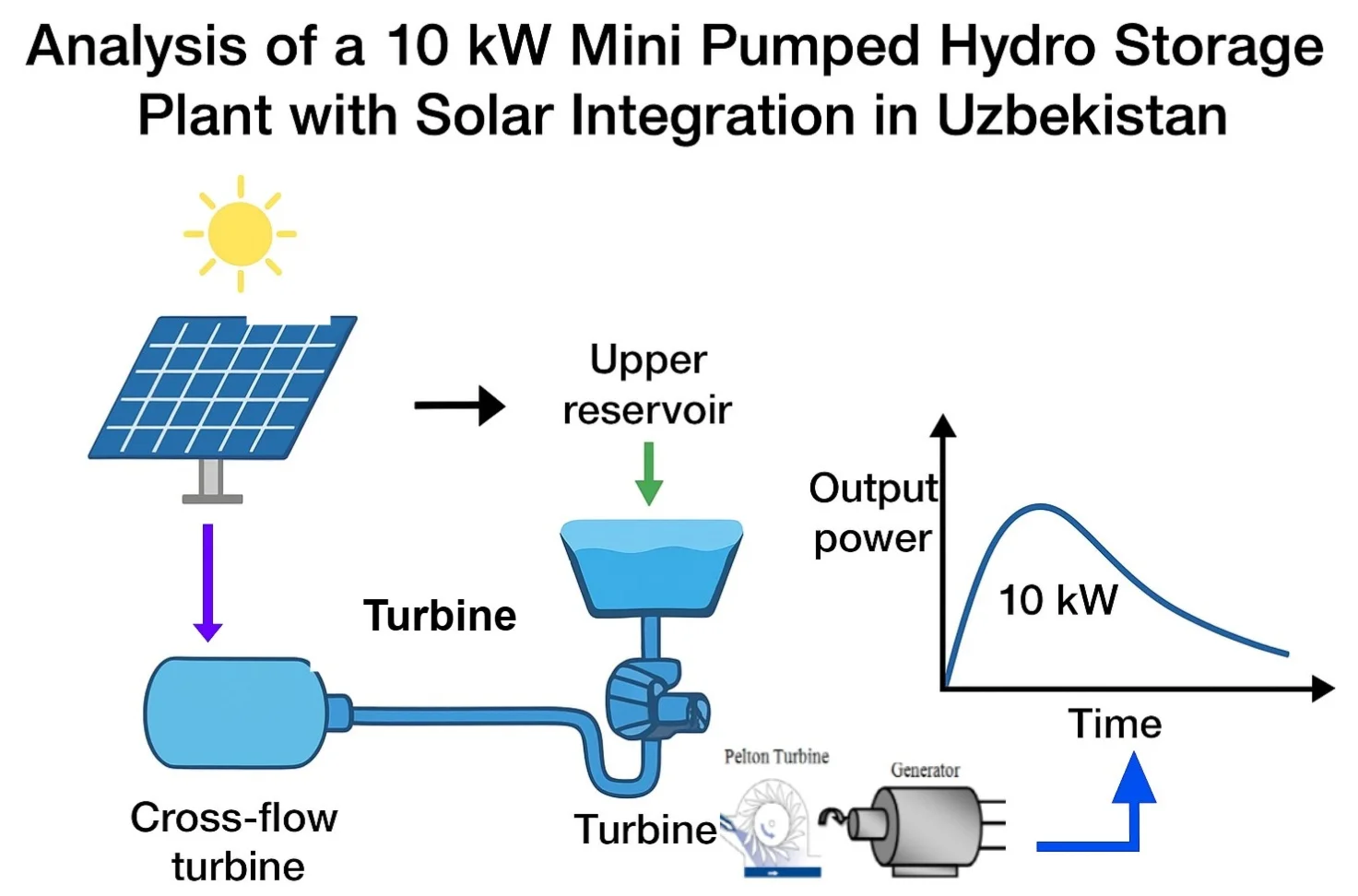

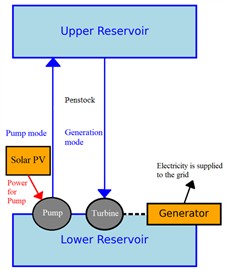

This paper presents the design and performance evaluation of a 10 kW mini pumped hydro storage (PSH) system integrated with solar photovoltaic (PV) energy for rural electrification in Uzbekistan. The system stores excess solar energy during the day and generates 60 kWh electricity during evening hours at a rated power of 10 kW, with an overall efficiency of about 75 %. The optimized design includes a Cross-Flow turbine (200 mm diameter, 600 rpm), a 10 m head, and 58 solar panels of 400 W. The study demonstrates that such small PSH systems can provide a cost-effective, long-lifetime alternative to chemical batteries in rural power applications.

Highlights

- A mini 10 kW pumped hydro storage system integrated with solar energy was designed and evaluated for stable off-grid power generation.

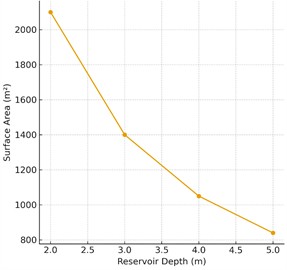

- The reservoir geometry and water surface area were analyzed to determine optimal depth–volume characteristics for energy storage cycles.

- Hydraulic losses, pumping head, and turbine efficiency were calculated to estimate overall system performance under varying operating conditions.

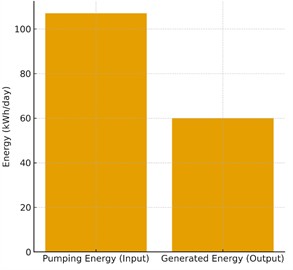

- Energy balance analysis showed that 106 kWh of input energy yields 60 kWh of output, confirming the viability of small-scale PSH systems.

- A cross-flow turbine configuration was optimized based on head, discharge, and runner diameter to meet the 10 kW design requirement.

1. Introduction

Pumped storage power plants (PSH) are recognized as the most reliable and scalable energy storage technology, with a round-trip efficiency ranging from 70 % to 85 % (IEA, 2020). They play a key role in balancing the variable output of renewable energy sources and in stabilizing power systems. In Uzbekistan, where the average solar radiation is 5-5.5 kWh/m2 per day, solar generation is one of the fastest growing technologies. However, its variability remains a serious challenge, especially in rural and autonomous areas [1].

Worldwide, pumped storage generation accounts for more than 90 % of installed energy storage capacity, with the largest stations operating in China, the USA, Japan, and Europe [2]. While large PSH plants have traditionally dominated, in recent years there has been increasing interest in small and mini systems (< 100 kW) designed for local needs [3]. Such systems are particularly relevant for Central Asia, where grid expansion is expensive and the terrain is favorable for hydropower development. Mini-PSH provides a sustainable solution for balancing solar generation without the use of costly chemical batteries. Compared to lithium-ion storage, they have a longer lifetime (30-50 years versus 8-12 years for lithium-ion batteries), lower operating costs, and minimal environmental impact, whereas chemical batteries are characterized by high cost, limited capacity, and the need for recycling [4]. Most existing research on pumped storage systems has focused on large-scale plants with capacities above 100 MW, while the potential of mini-PSH (< 100 kW) remains insufficiently studied. In particular, very few studies have been carried out for Central Asia, where solar insolation is high but centralized electricity supply in rural areas is limited. Thus, there is a research gap related to the adaptation of mini-PSH for the conditions of Uzbekistan, which this work seeks to address.

2. Literature review

Small and micro-hydropower plants are actively studied as decentralized solutions for rural electrification. [5] identified their global potential, emphasizing adaptability to remote areas. Later, [6] reviewed new developments in turbines and generators, making mini-hydropower more economical. Cross-Flow turbines have received particular attention due to their simplicity, low cost, and stability under variable discharge conditions [7]. The integration of pumped storage with renewable energy sources has been implemented in a number of hybrid systems. [8] showed that solar-PSH hybrids can smooth fluctuations in solar panel output. Similar conclusions were made by [9] for “wind-PSH” systems in Korea. For arid and semi-arid regions, solar-hydro hybrids are particularly advantageous because of high solar insolation [10].

Research on small PSH plants has begun to grow actively in recent years. [11] demonstrated the feasibility of micro-PSH systems for autonomous Turkish villages, showing that capacities of 5-20 kW are sufficient for stable electricity supply. Similar studies in India [12] confirmed the economic viability of small PSH in combination with solar power plants. Nevertheless, challenges remain: the need for land for reservoirs, high capital thresholds, and efficiency losses at small scales [3]. However, modular design and new materials are gradually reducing costs. Thus, there is a clear research gap in the application of mini-PSH in Central Asia, which defines the relevance of this article. The use of intelligent sensors to measure and control the rotational angular displacement of micro-engines increases their performance. Such intelligent sensors have been used in agricultural machinery [13-15]. Today, such hybrid energy systems are being used in various regions of Uzbekistan [16]. In addition, mini and micro hydropower plants do not affect the structural composition of water [17]. It is even possible to power some actuators with solar panels [18].

3. Materials and methods

The study applies mathematical models of hydropower processes that describe the conversion of the potential energy of water into electrical power, as well as determine the parameters of the pump-turbine cycle. The methodology includes:

– Energy model: the power equation , describing the dependence of output power on head and discharge.

– Cycle energy balance: calculation of input and output energy taking into account efficiency, which makes it possible to determine the effectiveness of pumped hydro storage.

– Hydraulic models: equations for calculating flow velocities, pipe diameters, and hydraulic losses during pumping and generation.

– Reservoir geometry model: determination of the relationship between surface area and depth for a fixed storage volume.

– Parametric optimization method: selection of optimal Cross-Flow turbine parameters (speed ratio, rotational frequency, runner diameter) to match the generator and ensure maximum efficiency. Based on these models, calculations were carried out for the parameters of generation, reservoir, pumps, turbine, and solar integration, which are presented below.

Initial parameters: Evening generation time: 6 h. Daytime pumping time: 5 h. Power: 10 kWh. Head: 10 m.

Water pumping and solar integration discharge during generation: 0.136 m3/s, where – efficiency (assumed 0.75), – water density (1000 kg/m3), – gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s2), – discharge (m3/s), – head (m).

Active water volume to be discharged during generation: 0.136⋅6⋅3600 = 2937.6 m3. Pumping discharge: = 0.163 m3/s (585 m3/h). Water energy will be: 288178560 J ≈ 80.05 kWh. Taking into account cycle efficiency (~75 %) the required energy is: = 106.73 kWh.

With average solar insolation of 5 h/day, the required solar power considering a 10 % reserve (dust, temperature, tilt angle) is: = 23.48 kW.

Taking into account losses, starting torque, and possible efficiency reduction, a pump with a reserve of 25 kW is selected.

Solar panels used: = 400 Wh, in quantity: 58. Total area of panels: 116 m2, where the area of one panel 2 m2.

Table 1Final calculated parameters of the 10 kWh mini-PSH with solar panel integration.

Parameters | Names | Magnitude |

Generation power | 10 kW | |

Head | 10 m | |

Water discharge during generation | 0.136 m3/s | |

Pumping discharge | 0.163 m3/s | |

Active water volume | 2937.6 m3 | |

Water energy | 80.05 kWh | |

Energy considering efficiency | 106.73 kWh | |

Solar panel power with reserve | 23.48 kW | |

Number of panels | 58 units | |

Total area of panels | 116 m² |

Hydraulic Elements. Jet velocity during generation (discharge): 13.73 m/s, where 0.98 is the nozzle velocity coefficient for a cross-flow turbine.

Pipe diameter calculation formula: .

Generation pipe. Diameter: 0.112 m = 11.2 sm.

Cross-sectional area: 98.47 sm2.

Pumping pipe. Diameter: 0.322 m = 32.2 sm.

Water lifting velocity: = 2 m/s.

Cross-sectional area: = 813.91 sm2.

When sizing the pumping pipe, an optimal flow velocity of 2 m/s is considered. Higher velocities reduce the pipe diameter and material cost, but significantly increase hydraulic losses, energy demand, and risks such as erosion, noise, water hammer, and cavitation. Total reservoir volume. The total reservoir volume, including a 10 % dead storage allowance (to account for factors such as sedimentation, suction vortex, and safety margin), is: = 2937.6⋅1.1 = 3231.36 m3.

The water surface area is calculated as , and the reservoir area with side slopes is estimated as .

Based on the total volume 3231.36 m3, the reservoir dimensions for different depths are calculated and summarized in the Table 2.

Turbine selection. The type of turbine is chosen based on the following parameters shown in Table 3.

Based on the table, a Cross-Flow turbine is selected, as it is suitable for small/medium flows and low/medium heads. For 10 m, 0.136 m3/s, the Cross-Flow turbine provides a simple, cost-effective design with an efficiency of 0.75, and performs well under variable flow rates and water contamination.

Optimal speed ratio for Cross-Flow turbines: .

Peripheral (tangential) velocity of the runner: 0.45∙13.73 = 6.1785 m/s.

Relation between peripheral velocity, diameter, and rotational speed: , where is the rotational speed in revolutions per minute (rpm). Runner diameter: = .

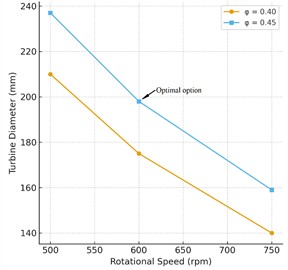

The turbine parameters are selected based on the following results shown in Table 4.

Table 2Reservoir parameters for different depths h

Parameters | Symbol | Depth 2 m | Depth 3 m | Depth 4 m | Depth 5 m |

Water surface area | 1615.68 m2 | 1077.12 m2 | 807.84 m2 | 646.27 m2 | |

Reservoir area with slopes | 2100.38 m2 | 1400.26 m2 | 1050.19 m2 | 840.15 m2 | |

Reservoir dimensions (square, 1:1) | – | 45.8×45.8 m | 37.4×37.4 m | 32.4×32.4 m | 29.0×29.0 m |

Reservoir dimensions (rectangle, 1.5:1) | – | 56.1×37.4 m | 45.9×30.6 m | 39.8×26.5 m | 35.5×23.7 m |

Table 3Parameters of hydraulic turbines

Head () | Flow rate () | Turbine type |

High: 150-200 m | Low: 0.005-0.01 m3/s | Pelton |

Wide range: 10-300 m | Medium and high: 0.1 up to hundreds of m3/s | Francis |

Low: 2-30 m | High: tens to hundreds of m3/s | Kaplan or propeller |

Low and medium: 5-50 m | Low: 0.005-0.01 m3/s | Cross-Flow |

Table 4Runner diameter D at rotational speeds of 500, 600, and 750 rpm, and speed ratios φ= 0.4 and φ= 0.45

, rpm | (peripheral velocity, m/s) | , mm | Nozzle height , mm | Nozzle width , mm | |

0.40 | 500 | 5.49 | 210 | 21.0 | 472 |

0.40 | 600 | 5.49 | 175 | 17.5 | 567 |

0.40 | 750 | 5.49 | 140 | 14.0 | 708 |

0.45 | 500 | 6.18 | 237 | 23.7 | 419 |

0.45 | 600 | 6.18 | 198 | 19.8 | 502 |

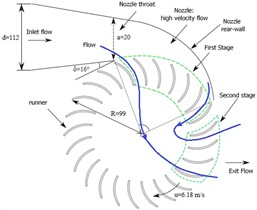

According to the table, the most optimal option is: 0.45, 200 mm, 600 rpm.

This combination provides:

– Good hydraulic performance.

– A convenient runner size.

Nozzle (slot) position relative to the turbine runner:

Jet angle – angle of attack relative to the tangent: 16 (recommended value). The jet entry point is located at the outer part of the runner. The distance from the nozzle edge to the runner contact point is about 1-2 jet thicknesses, which in this design corresponds to 19.8-39.6 mm. To ensure uniform filling of the inlet channels of the runner blades, the nozzle shape is designed along an arc.

Generator selection: For a mains frequency of 50 Hz and a turbine runner speed of 600 rpm, we use a generator with synchronous speed in the range 500-750 rpm. Based on the Table 5, a generator operating at 600 rpm corresponds to 10 poles.

4. Results and discussion

The designed mini-pumped storage power plant (mini-PSPP) provides evening electricity generation of 60 kWh with an installed capacity of 10 kWh over a period of 6 hours. To accumulate the required amount of energy, daytime pumping of approximately 107 kWh is needed, which corresponds to an overall cycle efficiency of about 75 %. Thus, the plant effectively compensates for the intermittency of renewable generation and ensures reliable coverage of the evening peak demand through hydro storage.

Fig. 1Nozzle and Cross-Flow turbine runner

Table 5Correspondence between generator poles and rotational speed (50 Hz)

Poles | Synchronous speed (rpm) |

2 | 3000 |

4 | 1500 |

6 | 1000 |

8 | 750 |

10 | 600 |

12 | 500 |

14 | 428.6 |

16 | 375 |

Table 6Generator parameters

Parameter | Value |

Generator type | Synchronous with AVR (automatic voltage regulator – stable frequency/voltage) |

Power | 12-15 kW |

Poles | 10 (for 600 rpm selection) |

Gearbox | Low-loss gearbox with protection against hydraulic water hammer |

The analysis of the relationship between reservoir water surface area and depth shows that increasing the depth from 2 m to 5 m reduces the surface area from 1615.68 m2 to 646.27 m2. This indicates that increasing the reservoir depth significantly reduces the required land area while maintaining the same storage volume. Therefore, selecting a greater reservoir depth is a more spatially efficient solution in the design of a pumped storage system.

Fig. 2Energy balance of the 10 kW mini-PSPP

Fig. 3Dependence of water surface area on reservoir depth

The calculation results show that increasing the rotor speed from 500 to 750 rpm at a fixed speed ratio leads to a reduction in the runner diameter (from 210 to 140 mm at 0.40; from 237 to 159 mm at 0.45). At the same time, the nozzle height decreases proportionally, while its width increases (from 472 to 708 mm at 0.40; from 419 to 624 mm at 0.45). This indicates that higher rotational speed allows the use of a more compact runner, but requires an elongated nozzle slot, which must be taken into account in turbine design.

Fig. 4Dependence of turbine diameter on rotational speed at φ= 0.40 and φ= 0.45

Fig. 5Schematic diagram of a 10 kW mini-PSPP with solar integration

Technical Advantages: stable daily operation, integration with solar panels smooths generation fluctuations, more cost-effective and durable compared to lithium-ion batteries, minimal carbon footprint.

Limitations: requires suitable topography for reservoirs, high capital investment, efficiency is sensitive to pipeline losses.

Sensitivity Analysis: a parametric sensitivity analysis was carried out with respect to head and flow rate . For variations of ±10 % and ±20 % from the design values, proportional changes in output power were observed (see Table 7). In particular, a simultaneous reduction of and by 10 % results in a power decrease of ≈19 %, highlighting the need for design margin in reservoir volume or backup pump capacity to ensure the rated output of 10 kW.

Table 7Proportional changes in output power were observed

(kW) | (%) | ||

−20 % | −20 % | 6.404 | −36.0 % |

−10 % | −10 % | 8.105 | −19.0 % |

0 % | 0 % | 10.006 | 0.0 % |

+10 % | +10 % | 12.108 | +21.0 % |

+20 % | +20 % | 14.409 | +44.0 % |

Comparison with previous studies (Table 8): the results of this work are compared with the studies of [11], [12] and [2]. All of these studies examine mini-PSH systems of similar scale (5-20 kW) and also highlight the advantages of pumped hydro storage over chemical batteries in terms of lifetime and maintenance cost. Unlike several works that rely on higher heads and larger reservoir surface areas, the proposed configuration ( 10 m, active volume = 3231.36 m3) achieves a comparable round-trip efficiency (~75 %) with a smaller land footprint due to the increased reservoir depth.

5. Conclusions

This study has developed and analyzed a 10 kWh mini pumped storage hydropower (mini-PSH) system integrated with solar photovoltaic generation for rural electrification in Uzbekistan. The obtained results confirm the technical feasibility of using small-scale PSH plants to store surplus solar energy during the day and supply stable electricity during evening peak hours. The designed system provides an average daily output of 60 kWh at a rated power of 10 kWh, achieving an overall round-trip efficiency of approximately 75 %.

Table 8Comparative summary of mini-PSH studies (Turkey, India, China, Uzbekistan)

Parameter | Ozturk et al. (Turkey, 2020) | Kumar & Singh (India, 2021) | Zhang et al. (China, 2021) | This work (Uzbekistan) |

System type | Micro-PSH with solar integration | Small PSH with solar PV | Large-scale PSH, < 100 kW noted as promising | Mini-PSH with solar integration |

Power rating | 5-20 kW | < 20 kW | Hundreds of MW-GW (small-scale considered promising) | 10 kW |

Key findings | Technically feasible and economically viable for rural areas | Alternative to batteries, suitable for decentralized supply | Large plants dominate, but small units are important for distributed energy | Feasible for rural electrification, 60 kWh/day, efficiency ≈ 75 % |

Limitations/ conditions | Requires suitable topography, reservoir costs | Dependent on hydrological conditions | Limited research on small-scale systems | Requires favorable terrain and investment in pumps and reservoirs |

Parameter | Ozturk et al. (Turkey, 2020) | Kumar & Singh (India, 2021) | Zhang et al. (China, 2021) | This work (Uzbekistan) |

The optimization of turbine dimensions and reservoir parameters demonstrates that such configurations can be effectively adapted to local geographic and climatic conditions. The proposed system represents a practical alternative to chemical energy storage, offering improved sustainability and reliability for decentralized power supply in rural regions. However, the research is limited to computational modeling and does not include experimental validation. Future studies should focus on prototype testing under real operating conditions, detailed evaluation of hydraulic losses, and comprehensive techno-economic assessment, including equipment costs and life-cycle efficiency. Overall, the presented concept contributes to the advancement of hybrid renewable energy solutions suitable for Central Asian rural areas.

References

-

S. Shakirov, D. Tadjibaeva, and A. Karimov, “Renewable energy development in Uzbekistan: Current status and future prospects,” Energy Reports, pp. 4720–4732, 2022.

-

C. Zhang, N. Zhang, and Y. Xu, “Global trends and future prospects of pumped storage hydropower,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, pp. 111–241, 2021.

-

S. Bremner, R. Lawrie, and L. Ozawa-Meida, “Small pumped storage hydropower: A review of opportunities and challenges,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, pp. 110–176, 2020.

-

J. K. Kaldellis and D. Zafirakis, “Optimum energy storage techniques for the improvement of renewable energy sources-based electricity generation economic efficiency,” Energy, Vol. 32, No. 12, pp. 2295–2305, Dec. 2007, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2007.07.009

-

O. Paish, “Small hydro power: technology and current status,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 6, No. 6, pp. 537–556, 2002.

-

J. R. Laghari, H. Mokhlis, A. H. A. Bakar, and M. Karimi, “A comprehensive overview of new designs in the hydraulic, electrical equipment and controllers of mini hydro power plants making it cost effective technology,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, pp. 279–293, 2013.

-

I. Alcántara-Ayala, J. M. Carrillo, and M. A. García, “Performance analysis of cross-flow turbines for micro-hydropower applications,” Renewable Energy, pp. 1580–1590, 2020.

-

A. H. Fathima and K. Palanisamy, “Optimization in microgrids with hybrid energy systems – A review,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 45, pp. 431–446, May 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.01.059

-

T. Lee, H. Kim, and J. Cho, “Integration of wind power with pumped storage in South Korea: A techno-economic analysis,” Applied Energy, p. 2019, 1201.

-

S. Ali, S. Rehman, and L. M. Alhems, “Solar-hydro hybrid renewable energy system: a sustainable solution for arid regions,” Renewable Energy, pp. 1452–1463, 2021.

-

M. Ozturk, S. Sahin, and M. Aydin, “Feasibility of micro pumped hydro energy storage systems in rural areas of Turkey,” Renewable Energy, Vol. 156, pp. 960–973, 2020.

-

A. Kumar and S. Singh, “Feasibility study of small pumped hydro storage for rural electrification in India,” Energy for Sustainable Development, Vol. 65, pp. 90–98, 2021.

-

R. Baratov and A. Mustafoqulov, “Smart angular displacement sensor for agricultural field robot manipulators,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 386, p. 03008, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202338603008

-

A. Mustafoqulov, R. Baratov, Z. Radjapov, S. Kadirov, and B. Urinov, “Angular displacement measurement and control sensors of agricultural robot-manipulators,” in BIO Web of Conferences, Vol. 105, p. 03003, Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/202410503003

-

R. Baratov and A. Mustafoqulov, “Model of field robot manipulators and sensor for measuring angular displacement of its rotating parts,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 401, p. 04006, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202340104006

-

A. Bokiev, S. Sultonov, N. Nuralieva, and A. Botirov, “Design of mobile electricity based on solar and garland micro hydro power plant for power supply in Namangan region mountain areas,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 365, p. 04003, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202336504003

-

E. Shipacheva, S. Shaumarov, A. Gulamov, M. Talipov, and S. Kandakharov, “Water Structure and Its Influence on Cement Stone and Concrete Properties,” in ICTEA: International Conference on Thermal Engineering, Vol. 1, No. 1, Jun. 2024.

-

D. D. Karimjonov, I. X. Siddikov, S. S. Azamov, and R. Uzakov, “Study on determination of an asynchronous motor’s reactive power by the current-to-voltage converter,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 1142, No. 1, p. 012023, Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1142/1/012023

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the administration of the “Tashkent Institute of Irrigation and Agricultural Mechanization Engineers” National Research University, for their continuous support and valuable contributions to the advancement of this research. Their encouragement and provision of academic resources have significantly facilitated the successful development of this study.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.