Abstract

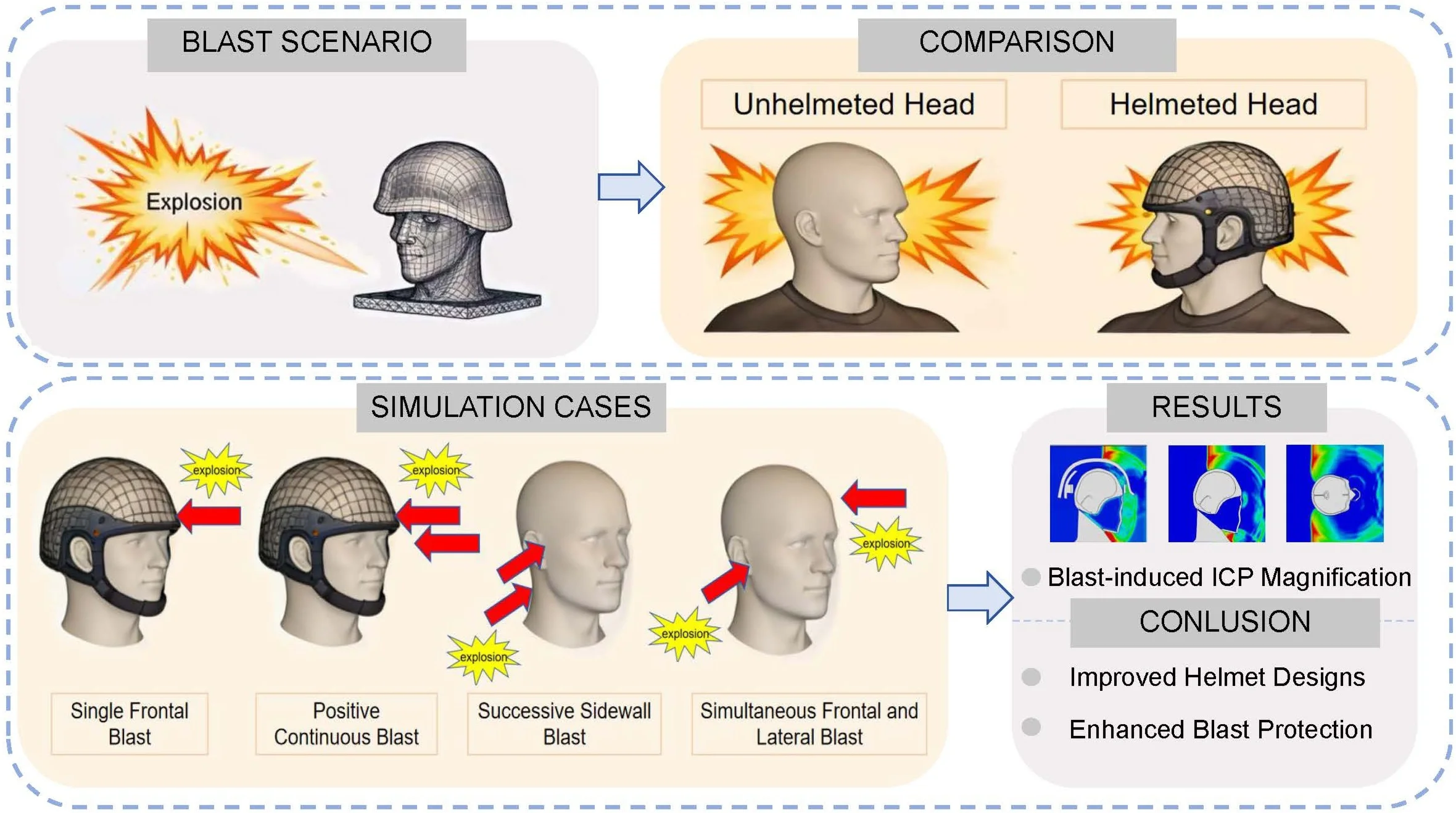

To systematically investigate the protective effects of helmets against human head injuries under various shock wave conditions, a finite element head-helmet coupling model was developed. This model analyzed how helmets influence biomechanical response parameters, such as intracranial and cranial pressure, when subjected to a single blast wave and its accompanying shock wave. While extensive research exists on single blast scenarios, studies on the more complex and militarily relevant accompanying shock waves, which pose a greater threat due to prolonged loading and multiple reflections, remain scarce. Several impact scenarios were considered, including single frontal impact, positive continuous impacts, successive sidewall impacts, and simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts. The study examined the dynamic changes in brain tissue within a blast environment to assess the efficacy of helmets in protecting the human head. In single frontal impact scenarios, helmets effectively reduced intracranial pressures in the frontal, occipital, and parietal lobes by 32 %, 38 %, and 19 %, respectively, while significantly decreasing the stress peak at the back of the skull. During positive continuous impacts, helmets decreased intracranial pressure in the parietal and occipital lobes by 36 % and 21 %, respectively, although their effectiveness in reducing frontal lobe pressure was limited due to inadequate facial protection. For successive sidewall impacts, helmet protection delayed the blast wave, reducing intracranial pressure in the frontal lobe by 60 kPa but increasing pressure in the parietal lobe by 80 kPa. This alleviated stress on the skull’s rear while increasing stress on the opposite side. In scenarios involving simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts, lateral blasts increased parietal intracranial pressure by 20 kPa, with the right hemisphere experiencing more pressure than the left due to the mitigating effect of reflective side blasts on skull stress. The study found that, compared to single blast waves, accompanying shock waves present a greater risk of cranial injuries due to their prolonged impact. These findings address a critical gap in blast neurotrauma research and provide valuable insights into the biomechanics of head injuries under realistic multi-blast conditions, which can directly inform the design of improved helmets with enhanced protection in complex blast environments. However, because shock waves may originate from multiple directions and elevations, the protective capability of conventional helmets for the facial region remains limited.

Highlights

- A novel numerical framework was established to explicitly incorporate accompanying shock waves into blast-induced head injury analysis.

- Four structured multi-directional blast–shock scenarios were designed to enable systematic and comparable biomechanical evaluation.

- The analysis reveals that facial exposure, rather than cranial shell response alone, governs helmet vulnerability under complex shock loading.

1. Introduction

In modern military and counter-terrorism operations, soldiers and personnel are frequently exposed to complex blast threats from improvised explosive devices (IEDs), grenades, or mortar rounds. These threats often generate not only a primary blast wave but also accompanying shock waves from reflections off nearby structures (e.g., buildings, vehicle interiors) or secondary explosions. This complex blast environment has led to a high prevalence of traumatic brain injuries (TBI), which account for 15 to 20 percent of all injuries in recent conflicts [1-2]. These injuries significantly impair neurological functions and quality of life, posing substantial challenges for medical treatment. The pattern of injuries from these complex explosions can vary significantly depending on the circumstances [3-5]. Although helmets are recognized as effective protective devices for the head, comprehensive research on their protective efficacy in various shockwave scenarios remains insufficient.

In recent years, scholars have conducted extensive research on shockwave-induced craniocerebral injuries. Singh et al. [6] utilized a multi-body model and a precise head model to recreate head kinematics during explosions, discovering that the height of the blast significantly impacted translational and rotational acceleration. Townsend et al. [7] evaluated brain material models within the blast-induced traumatic brain injury (bTBI) computational framework using both computational and experimental methods, concluding that variations in brain material parameters greatly influenced strain and intracranial pressure (ICP). Azar et al. [8] investigated factors affecting helmet protection effectiveness, revealing that goggles and helmets significantly reduced intracranial pressure and mechanical impact in simulations of head-on explosions and high frontal blunt impacts. Specifically, explosions reduced impact forces by 49 %-52 %, while impacts diminished cranial stress and intracranial pressure by 80 % and 84 %, respectively. Huang et al. [9] developed a shockwave-helmet-head fluid-solid coupling model to simulate helmet responses to shockwaves in explosive traumatic brain injuries. Their findings indicated that an advanced combat helmet (ACH) could reduce brain damage by approximately 5 %, whereas full-coverage helmets offered a 65 % reduction. Li et al. [10] utilized the cloudburst bomb static detonation test to identify shock waves and concrete debris as primary damaging elements and improved damage assessments by addressing the complex behavior of reflected shock waves on a humanoid device's surface. These insights provide valuable references for engineering applications and damage assessments. Ganpule et al. [11] explored helmet efficiency in mitigating IED shockwaves and determined that effectiveness was dependent on the helmet gap. Li et al. [12] examined helmet protection mechanisms against shockwaves from far-field explosions through experimental and numerical simulations, noting a reduction in peak overpressure at the top of the head but a potential increase at the rear. Despite the critical role of helmets in preventing shockwave-induced head injuries, their protective effects remain limited, underscoring the need for further research to enhance helmet design and materials [13-15]. In addition, the biomechanical response of cranial tissues under blast loading is strongly time-dependent and exhibits memory effects, which are not fully captured by classical integer-order models. Fractional calculus has recently emerged as a powerful mathematical framework for describing viscoelasticity and non-local interactions in biological tissues. Related studies demonstrated efficient techniques for solving fractional partial differential equations, explored theoretical properties through Mittag-Leffler functions, and developed numerical methods applicable to irregular geometries such as the head-helmet system [16-18]. These advances indicate that fractional-order modeling may enrich the theoretical framework of craniocerebral dynamics and provide complementary perspectives to finite element simulations.

However, the majority of the aforementioned studies, along with the current state of the literature, have primarily focused on the biomechanical response to a single, isolated blast wave. In real-world scenarios, such as breaching operations, vehicle underbody blasts, or complex urban environments, head exposure to multiple, accompanying shock waves from primary explosions, secondary reflections, or nearby simultaneous blasts is a prevalent and potentially more dangerous threat. The understanding of helmet performance under such complex, multi-blast loading conditions is critically lacking.

This study addresses a critical gap in blast-induced traumatic brain injury research by numerically investigating the protective efficacy of helmets under continuous and multi-directional shockwave loading – a scenario that more accurately reflects real-world blast exposures. Using a finite element head-helmet coupling model, we systematically analyzed key biomechanical response indicators, including intracranial pressure (ICP), cranial stress distribution, and shockwave propagation pathways, under both sequential and simultaneous blast waves.

Unlike prior studies limited to isolated single-blast scenarios, this work introduces a realistic multi-blast simulation framework to evaluate how helmet design influences brain injury risk under complex loading conditions. The findings provide new mechanistic insights into the dynamic interaction between blast waves and cranial structures, and offer evidence-based guidance for the development of next-generation helmets with enhanced protection against realistic multi-blast threats.

2. Models and methods

2.1. Establishment of head-helmet finite element model

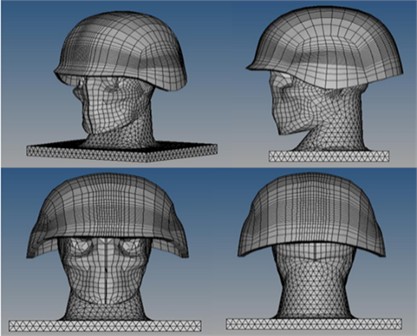

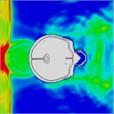

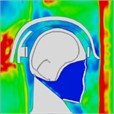

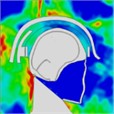

The finite element model of the human head-helmet system primarily consists of the skull (including cortical and trabecular bones), brain, cerebellum, scalp, dura mater, meninges, pons, falx, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The helmet model was constructed from Kevlar® K129 material [19] and was secured with straps; notably, it did not include foam padding for impact absorption, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1Head-helmet finite element model

The entire modeling and simulation process was conducted using a suite of commercial engineering software. The three-dimensional geometry of the neck was created using SOLIDWORKS™. All finite element simulations were solved using the explicit dynamics solver of Abaqus/Explicit™. Pre-processing tasks within the Abaqus environment, such as assigning material properties and defining boundary conditions, were completed using Abaqus/CAE™. Finite element pre-processing, including the importing of geometry, detailed meshing, and model assembly (e.g., sealing the gap between the neck and head), was performed using Altair HyperMesh™. The material properties of the head and helmet are detailed in Table 1. The parameters for the soft tissue of the neck were sourced from the literature [19].

Table 1Material characteristics of the head model

Performance data for head modelling materials | Densities(g/cm3) | Modulus of elasticity (GPa) | Poisson’s ratio |

Cortical bone | 2.00 | 15 | 0.22 |

Cerebrospinal fluid | 1.04 | 0.00015 | 0.499989 |

Dura mater | 1.14 | 0.0315 | 0.45 |

Face | 2.50 | 5.54 | 0.22 |

Cerebral scythe | 1.14 | 0.0315 | 0.45 |

Cerebellum | 1.04 | 0.000123 | 0.49 |

Neck (soft tissue) | 1.06 | 0.11 | 0.45 |

Soft mening meninges | 1.13 | 0.0115 | 0.45 |

Scalp | 1.13 | 0.0167 | 0.42 |

Cerebral Curtain | 1.14 | 0.0315 | 0.45 |

Trabecular bone | 1.30 | 1 | 0.24 |

Upper brain (cerebrum) | 1.04 | 0.00219 | 0.4996 |

2.2. Loads and boundary conditions

This study investigated the clearance pressures between the helmet and the head model at various blast positions, with a focus on the effects of blasts from the side, rear, and front on the head. The analysis was limited to direct impacts on the front plane of the head or face, given that frontal blasts typically result in the most severe head injuries. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of potential damage caused by blasts, a simulation scenario was employed to assess both a sustained frontal blast and the impact on the side of the head.

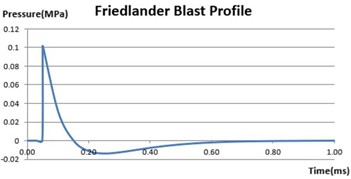

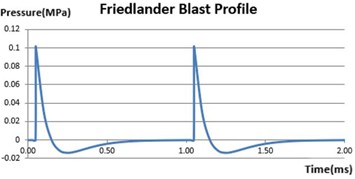

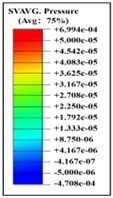

In this investigation, the Friedlander equation was employed to compute a blast pulse simulating the detonation of a TNT explosive, resulting in a planar overpressure of 1 atm (100 kPa) [20]:

where is the peak pressure and is the overpressure explosion duration, the explosive profile for this application is remarkably similar to the MIHRADI [21]. Furthermore, according to the literature review [21], Friedlander shock waveforms with a peak overpressure of 1 atm have been extensively applied. The Eulerian boundary defines conditions for independent inflow and outflow. The functional properties of Eulerian boundary conditions include: (1) defining the pressure field at the boundary, (2) regulating the flow of material into the Eulerian domain, (3) modeling an infinite domain by establishing non-reflecting boundary conditions at truncated artificial boundaries, and (4) associating with surfaces on the Eulerian mesh boundary where inflows or outflows occur [19].

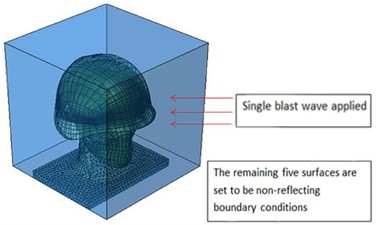

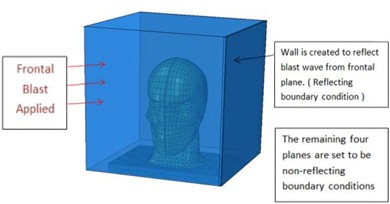

2.2.1. Single frontal shock wave simulation

Non-reflective boundary conditions were employed on artificial boundaries to model infinite domains. As illustrated in Fig. 2, these conditions were applied in a single planar explosion, utilizing five non-reflective surfaces with free-flow boundary conditions to permit material inflow and outflow. It is essential to manage the outflow of air to prevent the development of an environment with excessive negative pressure. To minimize the reflection of expansion and shear wave energy back into the model, non-reflective and equilibrium outflow boundary conditions were utilized [21]. The blast profile at this condition is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2Single frontal impact and non-reflective boundary conditions on other surface

Fig. 3Blast profile for single planar blast

Fig. 4Blast profile for two continuous blast waves

2.2.2. Simulation of accompanying shock waves

2.2.2.1. Positive continuous impacts

In this simulation, the head target was assumed to be located in the far-field of the explosion source, a condition where the curvature of the shock wave front is negligible and it can be accurately modeled as a planar wave impinging on the target. This allows us to isolate and study the effects of wave interaction without the complicating factors of spherical wave decay and complex geometry. Meanwhile the head target was subjected to two successive frontal blasts and two planar shock waves, each with an intensity of 1 atm. The blast waveform, as illustrated in Fig. 4, was utilized, and boundary conditions were established as a non-reflective border between free inflow and equilibrium outflow to accurately recreate this event. To validate the analytical results, the explosion test scenarios were examined using simulated head models both with and without helmets.

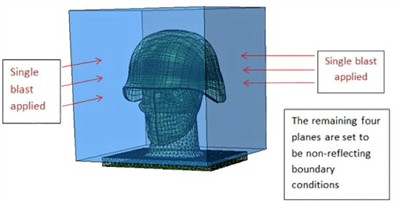

2.2.2.2. Successive sidewall impacts

In this scenario, two successive explosions impacted the frontal plane, or face, of the head. To simulate the worst-case scenario where the head is adjacent to a rigid, perfectly reflective wall. The wall was positioned to ensure full reflection of the incident shock wave onto the head model, which is the primary mechanical load of interest in this study, the left side of the cube’s transverse plane was configured as a reflective boundary wall measuring 330×330×6 mm. The other four planes were set with non-reflective boundary conditions to allow for “free inflow and equilibrium outflow”, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The blast profile in this condition is similar to that of positive continuous impacts.

2.2.2.3. Simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts

This scenario was designed to simulate simultaneous frontal and lateral blast waves impacting the head. In this configuration, the lateral and frontal explosions occurred concurrently, enabling a comparative analysis of their combined impact on head injuries as opposed to a single frontal blast. Examples of lateral and frontal blast waveform are presented in Fig. 4, with the boundary conditions detailed in Fig. 6.

Fig. 5Boundary conditions applied in continuous lateral impact

Fig. 6Boundary conditions applied in synchronous frontal side impact

3. Results

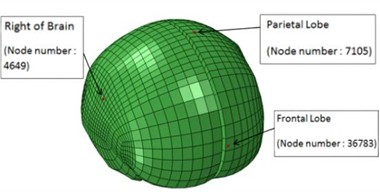

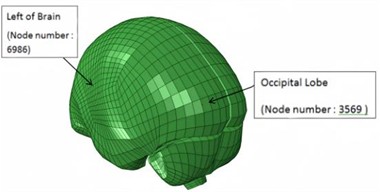

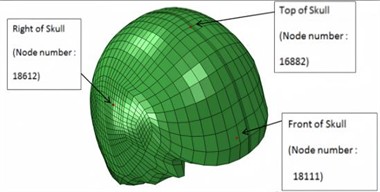

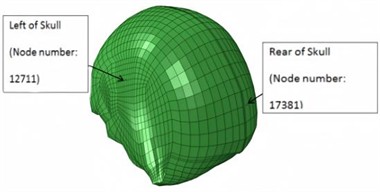

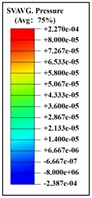

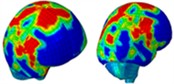

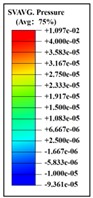

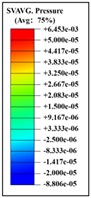

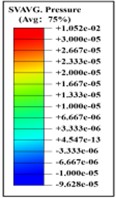

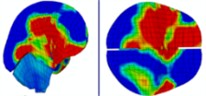

Based on intracranial pressure (ICP) tolerance criteria derived from brain damage analyses and in vivo animal testing, a peak ICP exceeding 235 kPa can result in severe brain damage, while an ICP below 173 kPa is likely to cause only mild or negligible damage [22]. Shear deformation of the brain occurs when brain tissue is displaced or distorted in different directions due to external forces, such as blast shock waves. This phenomenon can significantly affect the brain’s structure and function, with an ICP of 15 kPa considered the threshold for the onset of injury [23]. Consequently, the severity of craniocerebral injury can be assessed by measuring intracranial pressure. Additionally, by comparing the cranial fracture threshold established in biological experiments with cranial stress from analyses [23-24], von Mises cranial stress can serve as a crucial parameter for evaluating cranial stress. The locations of the measurement nodes for ICP and cranial stress are shown in Figs. 7-8.

Fig. 7Location of nodes at the brain where intracranial pressure is measured

Fig. 8Location of nodes at skull where stresses are measured

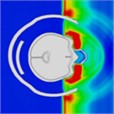

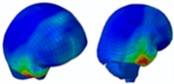

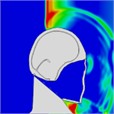

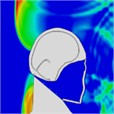

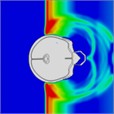

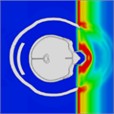

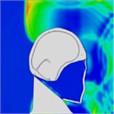

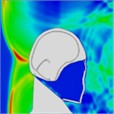

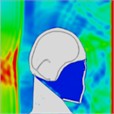

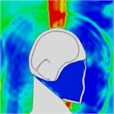

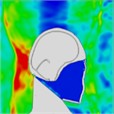

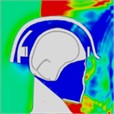

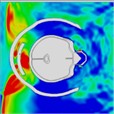

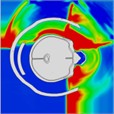

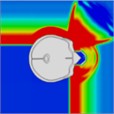

3.1. Simulation results of a single frontal impact

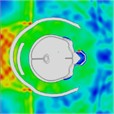

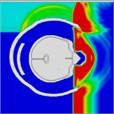

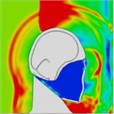

By examining the propagation of blast shock wave over the head with a helmet, researchers found that the wave impacts the face at approximately 0.35 ms, with high pressure gradually accumulating in the space between the jawbone and the neck. However, because the blast wave reflects off the front of the helmet, there is no direct impact on the skull, resulting in reduced pressure on it. As depicted in Table 2, the blast wave enters the helmet from both sides and reaches the back of the head at 0.8 ms.

Table 2Pressure distribution of a single frontal impact on the head while wearing a helmet

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 0.1 ms | Time = 0.2 ms | Time = 0.3 5 ms | Time = 0.4 ms | Time = 0.85 ms | Time = 1.05 ms |

Based on the analysis of intracranial pressure distribution data, the temporal lobe on the side of the head experiences higher pressure initially, at approximately 0.55 ms. The intracranial pressure then propagates from the anterior to the posterior regions between 0.60 ms and 1.0 ms. At 0.675 ms, the shockwave impacts the anterior side of the head, causing cranial stress to spread from the anterior to the parietal area over approximately 1.050 ms. Subsequently, cranial stress progresses from the top to the back of the head at 1.325 ms. However, cranial stress returns to the anterior portion of the skull between 1.425 ms and 1.85 ms. Table 3 illustrates the distribution of intracranial pressure for a single frontal impact.

Table 3Distribution of intracranial pressure in a single frontal impact

|  |  |  |  |

Time = 0.350 ms | Time = 0.550 ms | Time = 0.650 ms | Time = 0.825 ms | |

|  |  |  | |

Time = 1.025 ms | Time = 1.325 ms | Time = 1.425 ms | Time = 1.850 ms |

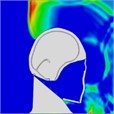

When a blast wave strikes an unhelmeted head, in comparison to one wearing a helmet, the wave directly impacts the skull for approximately 0.275 milliseconds. Moreover, the blast wave generates a pressure ring at the back of the skull, causing increased pressure that persists for about 0.8 milliseconds. Table 4 illustrates the pressure distribution on the skull.

Table 4Single frontal impact head pressure distribution without wearing a helmet

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 0.275 ms | Time = 0.475 ms | Time = 0.600 ms | Time = 0.700 ms | Time = 0.800 ms | Time = 0.900 ms |

According to Grujicic et al. [3], a single blast wave simulation of the Friedlander blast distribution was conducted for both helmeted and unhelmeted heads. The results indicated that intracranial pressure in an unhelmeted head ranged from 0 to 120 kPa. In contrast, the Advanced Combat Helmet (ACH) effectively provided head protection, maintaining pressures between –80 kPa and 80 kPa [21]. Comparing these simulation results with existing literature revealed a broader range of intracranial pressures, possibly because the foam padding in the helmet model did not perform as expected [21]. Furthermore, a study by Tan et al. [19] noted that the cranial force on a helmeted head should range between 6 and 11 MPa when simulating a 1 atm overpressure TNT explosion. A comparison of these results with literature data showed a slightly lower cranial stress level, which might be attributed to differences in the biological head materials used in the two simulations.

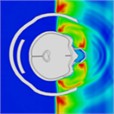

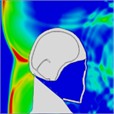

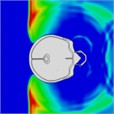

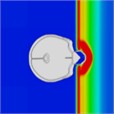

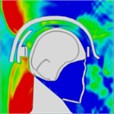

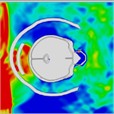

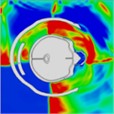

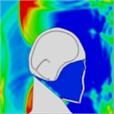

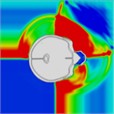

3.2. Simulation results of positive continuous impacts

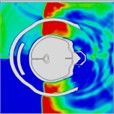

When a helmet is worn, the blast’s shock wave initially strikes the face and then concentrates behind the lower jaw for approximately 0.375 ms. Importantly, the shock wave does not directly contact the skull; instead, it reflects off the front of the helmet, thereby mitigating direct impact on the skull. At 0.375 ms, the blast wave enters the helmet through the side openings, as shown in the head pressure distribution plot (Table 5). When the helmet padding is replaced by a helmet band, the shock wave flows into the gap between the head and the helmet and then exits from the back. Consequently, the shock wave wraps around the back of the head and affects the occipital part of the optic nerve. At 0.975 ms, a negative pressure causes the blast wave to return to the back of the head, and at 1.2 ms, a second blast impacts the face while enveloping the front and sides of the head. The blast wave focuses on the sides at the gap between the head and helmet, subsequently moving to the back of the helmet, where it accumulates at 1.97 ms. By 2.15 ms, the blast wave flows back to the front of the head, with the shock wave accumulating in the gap between the head and helmet. By 2.7 ms, most of the blast wave has gathered at the front of the head.

Table 5Pressure distribution of continuous frontal impact head while wearing a helmet

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

Time = 0.250ms | Time = 0.375 ms | Time = 0.475 ms | Time = 0.700 ms | Time = 0.900 ms | Time = 1.100 ms | |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 0.250 ms | Time = 0.375 ms | Time = 0.850 ms | Time = 0.975 ms | Time = 1.250 ms | Time = 1.825 ms | |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 1.975 ms | Time = 2.075 ms | Time = 2.150 ms | Time = 2.700 ms | Time = 2.900 ms | Time = 3.000 ms |

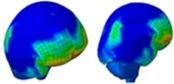

Based on the analysis of intracranial pressure distribution, it was observed that the shock wave first reached the frontal lobe from the temporal lobe within 0.5 ms. Subsequently, high intracranial pressure spread and propagated from the anterior and posterior regions of the brain. At 1.0 ms, as the blast’s shock wave became concentrated, the intracranial pressure converged in the area of the lateral ventricle, located at the brain's center. At 1.325 ms, a second blast continued to impact the face, transmitting pressure to the brain through the soft tissues and skull. This process again subjected areas of the brain, including the frontal and temporal lobes, to high pressure. Immediately afterward, the pressure wave spread and propagated once more from the front and back of the brain, with the central regions again experiencing high pressure. Compared to the results of a single-plane explosion, the lateral ventricles experienced a higher degree of intracranial pressure buildup, regardless of helmet use. This suggests that the impact from the second explosion could result in more severe brain damage. The distribution of intracranial pressure is illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6Distribution of intracranial pressure during continuous frontal impact

|  |  |  | |

Time = 0.300 ms | Time = 0.500 ms | Time = 0.700 ms | ||

|  | |||

Time = 1.000 ms | Time = 1.325 ms | |||

An analysis of head explosions under both helmeted and unhelmeted conditions revealed certain variations as well as commonalities. Specifically, at 0.25 ms, the sagittal distribution of impact pressure indicated that the blast shockwave affected both the face and the skull, suggesting direct impact on the skull in the unhelmeted condition. This is similar to the helmeted condition, where the shock wave envelops the back of the head at 0.8 ms and 1.7 ms. When a helmet is worn, the posterior part of the head is protected, reducing the pressure on the occipital lobe. Therefore, without helmet protection, the blast's effect on the back of the head might be more pronounced. The pressure distribution on the head without a helmet is illustrated in Table 7.

Table 7Continuous frontal impact head pressure distribution without wearing a helmet

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 0.250 ms | Time = 0.625 ms | Time = 0.800 ms | Time = 1.025 ms | Time = 1.425 ms | Time = 1.750 ms |

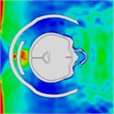

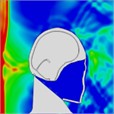

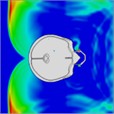

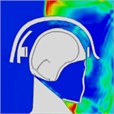

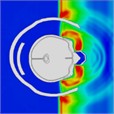

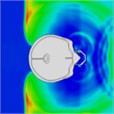

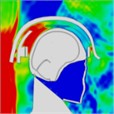

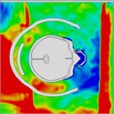

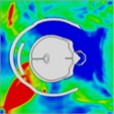

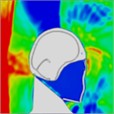

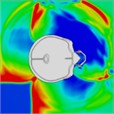

3.3. Simulation results of successive sidewall impacts

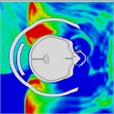

The pressure distribution diagram, used to analyze the impact of an explosion on a helmeted head, indicates that the left wall of the head model instantly reflects the initial forward shock wave after it strikes the surface. During the first phase, as the forward blast wave moves towards the back, the rebounded shock wave covers and reaches the back of the head. At 0.775 ms, a high-pressure wave appears behind the neck, potentially creating a “shock” effect at the back of the head. By 0.975 ms, the negative phase of the blast wave shifts, allowing the pressure wave from the first blast to intersect with the second blast wave at 1.175 ms. By 1.25 ms, high-pressure waves surround both the front and back of the head, subsequently gathering again. At 1.775 ms, the high-pressure wave concentrates at the back of the neck. At 1.875 ms, due to changes in the second blast wave, the high-pressure wave moves back to the front of the head. By 2.175 ms, the pressure wave is trapped at the back of the neck and moves forward to the front of the head after reflection. By 2.875 ms, the high-pressure wave forms a ring around the front of the head. The head pressure distribution is illustrated in Table 8.

Table 8Pressure distribution of continuous lateral impact on the head when wearing a helmet

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

Time = 0.300 ms | Time = 0.500 ms | Time = 0.775 ms | Time = 0.975 ms | Time = 1.175 ms | Time = 1.250 ms | |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 1.775 ms | Time = 1.875ms | Time = 2.100 ms | Time = 2.175 ms | Time = 2.875 ms | Time = 2.975 ms | |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 0.275 ms | Time = 0.500 ms | Time = 0.625 ms | Time = 0.800 ms | Time = 0.925 ms | Time = 1.100 ms |

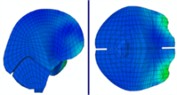

The intracranial pressure distribution graph indicates that high intracranial pressure gradually propagates from the anterior to the posterior part of the brain between 0.225 ms and 0.475 ms. The left side of the occipital and temporal lobes experiences numerous positive pressure spikes as the shock wave rebounds off the wall. Additionally, the right side of the head is subjected to high pressure at 1.325 ms. The accumulated high-pressure wave on the right side of the head is alleviated when a helmet is worn. This suggests that wearing a helmet reduces intracranial pressure on the right side of the brain. The intracranial pressure distribution is illustrated in Table 9.

Table 9Intracranial pressure distribution of continuous lateral impact

|  |  |  | |

Time = 0.225 ms | Time = 0.275 ms | Time = 0.425 ms | ||

|  | |||

Time = 0.475 ms | Time = 1.350 ms | |||

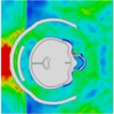

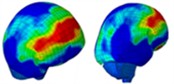

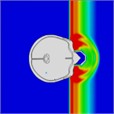

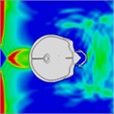

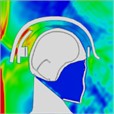

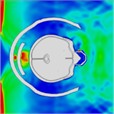

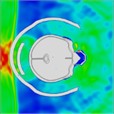

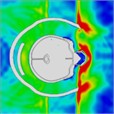

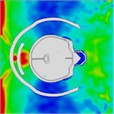

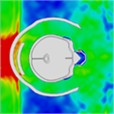

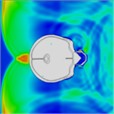

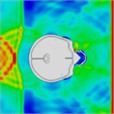

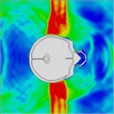

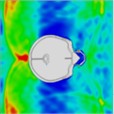

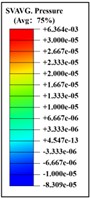

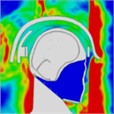

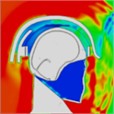

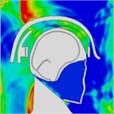

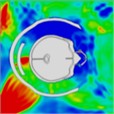

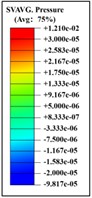

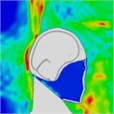

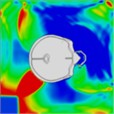

3.4. Simulation results of simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts

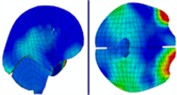

Simulation results indicate that the explosion initially impacts the left side of the head. At 0.4 ms, high-pressure waves are present on this side. By approximately 0.75 ms, these waves converge on the right side of the head. At 0.85 ms, high-pressure waves spread to the back and left side of the head, resulting in a “shock” effect. During this time, the high-pressure wave produces an “impact” on these areas. The wave begins to wrap around the head, and by about 1.3 ms, it starts to completely envelop it once more. By 2.0 ms, the head is fully surrounded by the blast wave.

Initially, the peak intracranial pressure (ICP) in the left temporal lobe appears at 0.275 ms, with ICP spreading from the front to the back of the head. High ICP is observed in the parietal lobe between 0.675 ms and 0.8 ms. By 1.225 ms, high ICP is concentrated in the lateral ventricles or nuclei of the brain, indicating that intracranial pressure is transmitted from the outside to the inside of the brain. At 1.7 ms, a significant increase in ICP occurs in the right temporal lobe, likely due to the shock wave converging on the right side and creating a powerful impact. Finally, at 2 ms, most of the brain tissue, including the lateral ventricles, experiences a very high ICP shock. The head pressure distribution is illustrated in Table 10.

Table 10Pressure distribution of synchronous frontal side impact while wearing a helmet

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

Time = 0.250 ms | Time = 0.450 ms | Time = 0.650 ms | Time = 0.850 ms | Time = 1.025 ms | Time = 1.200 ms | |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 0.250 ms | Time = 0.325 ms | Time = 0.450 ms | Time = 0.775 ms | Time = 0.825 ms | Time = 0.875 ms | |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 1.050 ms | Time = 1.275 ms | Time = 1.325 ms | Time = 1.500 ms | Time = 1.750 ms | Time = 2.000 ms |

The pressure distribution graphs indicate that both helmeted and unhelmeted heads are subjected to similar explosion rates overall. However, the unhelmeted head exhibits significantly higher intracranial pressure on the left side compared to the helmeted head, likely due to the protective effect of the helmet. Table 11 illustrates the pressure distribution on the head without a helmet.

Table 11Pressure distribution of synchronous frontal side impact without wearing a helmet

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  | |

Time = 0.300 ms | Time = 0.400 ms | Time = 0.475 ms | Time = 0.650 ms | Time = 0.925 ms | Time = 1.15 ms |

4. Discussions

First, it is essential to thoroughly explain intracranial pressure (ICP). When comparing peak ICP from a single frontal impact with and without a helmet, it was found that wearing a helmet reduced ICP in the frontal lobe by 32 %, and in the occipital and parietal lobes by 38 % and 19 %, respectively. According to the head injury threshold [22], severe brain injuries are unlikely if ICP remains below 235 kPa. In sequential frontal impacts, the helmet reduced ICP in the parietal lobe by 36 % and in the occipital lobe by 21 %. However, ICP in the frontal lobe remained stable, suggesting that the helmet provides more substantial protection for the parietal region. Despite this, the benefit is not as pronounced because the parietal region is not the main pathway for stress transfer into the brain [25]. Severe brain injuries are more likely in unhelmeted heads, where ICP in the parietal lobe can reach 330 kPa, exceeding the 235 kPa threshold. Although helmets delay shock wave arrival, pressure waves can still reach the brain without helmet protection. Helmets can substantially reduce the speed of shock wave propagation in successive sidewall impacts. In both frontal and lateral continuous impact scenarios, helmet use decreased frontal lobe pressure from 220 kPa to 160 kPa, and increased it from 210 kPa to 290 kPa. Comparing data from these scenarios reveals an increase in ICP in the occipital lobe during sidewall impacts with a helmet, suggesting that blast wave reflection mainly occurs from the occipital area. Notably, ICP changes in the parietal and occipital lobes were insignificant without a helmet. ICP measurements in the temporal lobes revealed a significant increase on the left side, likely due to frontal wall reflection. Intracranial pressure in the parietal lobe was slightly higher during simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts than during single frontal impacts; however, ICP in the frontal and occipital lobes remained similar between the two scenarios, indicating that additional lateral blasts primarily affect parietal ICP. This suggests that lateral blasts are unlikely to cause severe brain damage, as the parietal lobe is not the main route for pressure entry compared to single blasts. In simultaneous impacts, the effect on the frontal lobe is more significant than on the lateral aspect. Furthermore, higher ICP on the right side of the brain compared to the left might result from reflections from frontal and lateral blasts. According to the blast-induced head injury threshold, there is a potential for severe brain injury with simultaneous impacts, regardless of helmet use [22]. This means the additional lateral blast does not significantly raise the risk of severe brain injury.

Secondly, a detailed examination of cranial von Mises stresses is needed. In a single frontal impact, the stresses in the frontal and parietal regions were almost unchanged between unhelmeted and helmeted heads. However, the posterior cranium of the helmeted head experienced relatively higher stress intensities, suggesting that helmets can effectively reduce peak stress at the back of the skull. In positive continuous impacts, cranial stress in the frontal region of helmeted heads was significantly higher than in unhelmeted ones, potentially due to the blast wave between the helmet's front and the forehead, which could increase frontal lobe ICP. When comparing helmeted and unhelmeted states, stresses in the parietal and posterior sections of unhelmeted heads were relatively higher. Thus, helmets provide some relief from shock waves in these areas. In successive sidewall impacts, stress magnitudes did not change significantly in the front and left sides of the head, while stress at the back of the head slightly decreased with helmet use, demonstrating helmet effectiveness. However, stress on the right side increased with a helmet. Graphically, helmeted heads showed one significant peak stress of 10 MPa, with cranial stresses fluctuating between 4 MPa and 6 MPa, whereas unhelmeted heads showed multiple peaks between 6 MPa and 8 MPa. This highlights the helmet’s role in reducing stress intensity on the right side of the skull. Helmets effectively reduce cranial stresses in the frontal, parietal, posterior, and left sides in simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts, significantly lessening the blast wave's impact on the brain.

5. Conclusions

Based on the head-helmet model, this study systematically investigated the kinetic response of the cranium and brain, as well as the protective performance of helmets under the influence of a single blast wave and accompanying shock wave. It also focused on analyzing the propagation characteristics of blast waves and the mechanisms of cranial and brain injury under scenarios of positive continuous impacts, successive sidewall impacts, and simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts. The specific conclusions are as follows:

1) Wearing a helmet can significantly reduce intracranial pressure in the parietal and occipital lobes during positive continuous impacts. However, the frontal lobe is not as well protected. While the helmet provides clear protective benefits for the parietal and posterior regions of the head, it is not entirely effective in preventing stressors from spreading through the main transmission channels of the intracranial cavity. Therefore, individuals without helmets are more susceptible to serious brain injuries, particularly in the parietal area.

2) In the case of successive sidewall impacts, wearing a helmet significantly reduces intracranial pressure on the right side of the brain due to blast impact, thereby delaying blast wave propagation. However, in extreme cases, intracranial pressure in the parietal lobe may still exceed normal limits. Helmets substantially lower intracranial pressure in the frontal lobe compared to scenarios involving sequential frontal blasts, though the parietal and occipital lobes remain at risk, with elevated ICP in the occipital lobe possibly due to reflective effects. Despite helmets' ability to reduce stress peaks in the skull, severe brain injuries cannot be entirely prevented in extreme cases.

3) Compared to single blast simulations, the additional lateral blasts during simultaneous frontal and lateral impacts do not significantly affect intracranial pressure in the frontal and occipital lobes, but they notably increase pressure in the parietal region. In this scenario, helmets reduce the impact of blast shock waves on the brain and significantly lower intracranial pressure.

4) Wearing a helmet greatly delays the arrival time of blast waves in all simulations involving shock waves, thereby enhancing brain protection. However, the protective effect on the face is relatively limited.

References

-

Y. Li et al., “Review of mechanisms and research methods for blunt ballistic head injury,” Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, Vol. 145, No. 1, p. 01080, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4055289

-

Y. Li, H. Fan, and X.-L. Gao, “Ballistic helmets: Recent advances in materials, protection mechanisms, performance, and head injury mitigation,” Composites Part B: Engineering, Vol. 238, p. 109890, Jun. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.109890

-

A. Grujicic et al., “Potential improvements in shock-mitigation efficacy of a polyurea-augmented advanced combat helmet,” Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, Vol. 21, No. 8, pp. 1562–1579, Oct. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-011-0065-3

-

C. S. White, R. K. Jones, E. G. Damon, E. R. Fletcher, and D. R. Richmond, “The biodynamics of air blas,” Lovelace Foundation for Medical Education and Research, Albuquerque, Jan. 1971, https://doi.org/10.2172/4701469

-

S. G. Kulkarni, X.-L. Gao, S. E. Horner, J. Q. Zheng, and N. V. David, “Ballistic helmets – their design, materials, and performance against traumatic brain injury,” Composite Structures, Vol. 101, pp. 313–331, Jul. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2013.02.014

-

D. Singh and D. Cronin, “Multi-scale modeling of head kinematics and brain tissue response to blast exposure,” Annals of Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 47, No. 9, pp. 1993–2004, Jan. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-018-02193-x

-

M. T. Townsend, E. Alay, M. Skotak, and N. Chandra, “Effect of tissue material properties in blast loading: coupled experimentation and finite element simulation,” Annals of Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 47, No. 9, pp. 2019–2032, Dec. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-018-02178-w

-

A. Azar, K. B. Bhagavathula, J. Hogan, S. Ouellet, S. Satapathy, and C. R. Dennison, “Protective headgear attenuates forces on the inner table and pressure in the brain parenchyma during blast and impact: an experimental study using a simulant-based surrogate model of the human head,” Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, Vol. 142, No. 4, p. 04100, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4044926

-

X. Huang, L. Chang, H. Zhao, and Z. Cai, “Study on craniocerebral dynamics response and helmet protective performance under the blast waves,” Materials and Design, Vol. 224, p. 111408, Dec. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111408

-

G. Li et al., “Experimental research on lung injury of human under complex blast wave,” (in Chinese), Acta Armamentarii, Vol. 45, No. 5, pp. 1681–1691, 2024.

-

S. Ganpule, L. Gu, A. Alai, and N. Chandra, “Role of helmet in the mechanics of shock wave propagation under blast loading conditions,” Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 15, No. 11, pp. 1233–1244, Nov. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2011.597353

-

J. Li et al., “Protective mechanism of helmet under far-field shock wave,” International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 143, p. 103617, Sep. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2020.103617

-

Z. X. Duan et al., “Diagnosis and treatment of mild brain injury induced by explosive blast wave,” (in Chinese), Chinese Journal of Diagnostics (Electronic Edition), Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 26–29, 2016, https://doi.org/10.3877/cma.j.issn.2095-655x.2016.01.008

-

O. Rodriguez et al., “Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging as a diagnostic and dispositional tool after mild-moderate blast traumatic brain injury,” Journal of Neurotrauma, Vol. 33, No. 7, pp. 662–671, Apr. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2015.4002

-

Z. Cai, Z. Li, J. Dong, Z. Mao, L. Wang, and C. J. Xian, “A study on protective performance of bullet-proof helmet under impact loading,” Journal of Vibroengineering, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 2495–2507, Jun. 2016, https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2015.16497

-

H. K. Jassim, H. Ahmad, A. Shamaoon, and C. Cesarano, “An efficient hybrid technique for the solution of fractional-order partial differential equations,” Carpathian Mathematical Publications, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 790–804, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.15330/cmp.13.3.790-804

-

H. Ahmad, M. Tariq, S. K. Sahoo, J. Baili, and C. Cesarano, “New estimations of Hermite-Hadamard type integral inequalities for special functions,” Fractal and Fractional, Vol. 5, No. 4, p. 144, Sep. 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract5040144

-

F. Wang et al., “Meshless method based on RBFs for solving three-dimensional multi-term time fractional PDEs arising in engineering phenomenons,” Journal of King Saud University – Science, Vol. 33, No. 8, p. 101604, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101604

-

L. B. Tan, H. P. Lee, and V. B. C. Tan, “Ballistic impact analysis of an advanced combat helmet with interior cushioning system on a Hybrid3 headform,” in Defense Science Research Conference and Expo (DSR), Aug. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1109/dsr.2011.6026827

-

H. P. Lee and S. W. Gong, “Finite element analysis for the evaluation of protective functions of helmets against ballistic impact,” Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, Vol. 13, No. 5, pp. 537–550, Oct. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1080/10255840903337848

-

S. Mihradi, H. Homma, and Y. Kanto, “Numerical analysis of kidney stone fragmentation by short pulse impingement: effect of geometry,” Key Engineering Materials, Vol. 306-308, No. 2, pp. 1283–1288, Mar. 2006, https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/kem.306-308.1283

-

P. A. Taylor and C. C. Ford, “Simulation of blast-induced early-time intracranial wave physics leading to traumatic brain injury,” Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, Vol. 131, No. 6, p. 06100, Jun. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3118765

-

M. Rodríguez-Millán, L. B. Tan, K. M. Tse, H. P. Lee, and M. H. Miguélez, “Effect of full helmet systems on human head responses under blast loading,” Materials and Design, Vol. 117, pp. 58–71, Mar. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2016.12.081

-

A. M. Nahum, R. W. Smith, and C. C. Ward, “Intracranial response of a three-dimensional human head finite element model,” in Proceedings of Injury Prevention through Biomechanics Symposium, pp. 97–103, 1991.

-

K. H. Taber, D. L. Warden, and R. A. Hurley, “Blast-related traumatic brain injury: what is known?,” The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 141–145, Apr. 2006, https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.2006.18.2.141

About this article

We appreciate the editors and referees for their valuable remarks and advice, which have significantly enhanced the clarity of the paper. We would also like to express our gratitude for the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12372079), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (Grant No. BK20201470).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All figures are original and were generated by the authors from their own simulations, screenshots and data-visualisation workflows. This study involves no human or animal experiments.

Bin Yang, Jiajia Zou, Yang Zheng: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing-original draft preparation, visualization. Feng Gao, Xuan Ma, Xingyu Zhang, Hao Feng, Peng Zhang, Xinyu Wei, Li Li: conceptualization, investigation, validation, writing-review and editing, supervision.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.