Abstract

China is vigorously developing distributed small hydropower in rural areas. However, the large-scale integration of small hydropower into distribution networks causes voltage fluctuations and over-limits due to seasonal variations in power output. To ensure the safe and stable operation of the distribution network, a voltage optimization strategy based on the adaptive shrinkage factor particle swarm optimization (ASCF-PSO) algorithm is proposed. The strategy involves dividing small hydropower into clusters and coordinating the optimization of reactive power compensation devices and cluster output, with the goal of minimizing node voltage deviation and network loss under different spatiotemporal scenarios. Simulations conducted on a 33-node system using actual output data from multiple small hydropower stations in the Meijiang River Basin. It shows that ASCF-PSO can keep all node voltages within the normal range and improve the rationality of power distribution. This study provides an effective solution for the safe and stable operation of distribution networks with high penetration of small hydropower.

1. Introduction

In response to global challenges such as global warming and excessive greenhouse gas emissions, the State Council of China issued the action plan for carbon peaking by 2030, which included “carbon peaking” and “carbon neutralization” into the “14th five year plan” and medium- and long-term development strategies to achieve energy security and sustainable development [1]. China has vigorously promoted distributed generation (DG) across various regions, leading to a year-on-year increase in the penetration rate of renewable energy in power systems [2]. In water-rich areas, large-scale small hydropower grids have gradually formed. Small hydropower units are mainly distributed in rural and remote areas, connected to distribution networks as auxiliary power sources to complement the main power supply and support the main grid’s power dispatching. Typically, distributed small hydropower units are integrated into the low-voltage side of distribution networks.

In general, the output operation of small hydropower is relatively stable, and the voltage fluctuation range is smaller than that of wind power, photovoltaic and other distributed power sources. With installed capacities generally below 50 MW and voltage levels of 10-35 kV, most small hydropower units are run-of-river type, whose active power output depends heavily on river runoff. Therefore, there are problems such as seasonality, randomness of output, intermittence and greater impact by meteorological factors such as rainfall. The power generation characteristics of small hydropower units differ greatly in different spatiotemporal scenarios, and their grid connected capacity, location and active and reactive output have a great impact on the voltage of distribution network [3]. The imbalance between load power and small hydropower injection power [4] causes voltage fluctuations and over-limits in low-voltage distribution networks [5]. During the wet season, DG connected to the low-voltage distribution network has the phenomenon of reverse power flow, resulting in the line node voltage exceeding the upper limit [6], and serious reactive power surplus in the region; During the dry season, some DG units reduce output or shut down, failing to meet load demand and causing line node voltages to drop below the lower limit. Voltage instability or over-limits in distribution networks severely degrade power quality, reduce voltage qualification rates [7], and cause damage to user equipment. In the long run, it also fails to meet the economic and security needs of power grid companies.

In view of the voltage fluctuation and voltage out of limit caused by DG access to low-voltage distribution network, scholars worldwide have conducted in-depth research and proposed various solutions. In [8] proposes a multi-agent control system, which can globally correct voltage overruns and coordinate the operation of reactive power control devices. In [9] proposed a decentralized coordinated voltage control (CVC) scheme, which uses OLTC and other voltage regulating devices to achieve better voltage regulation and increase reactive power reserve under normal operation conditions of power grid. In [10]-[12] carry out DG optimal dispatch and reactive power and voltage control of power system based on particle swarm optimization algorithm. In [13] proposes a centralized support distributed voltage control algorithm, which uses -decomposition to decompose the distribution system into different regions, determines the effective position of injecting reactive power into the distribution system, and provides safe reactive power control. In [14] effectively utilizes and excavates the flexible regulation potential of small hydropower and uses the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm with elite strategy to solve the multi-objective model to realize the collaborative optimization of distribution network. In [15] and [16] provide scheduling strategies for the coordinated scheduling of distribution networks with DG to achieve the balance between network loss and voltage deviation. In [17] proposed a data-driven predictive voltage control method, which can improve the voltage suppression effect through boundary information interaction and inter regional coordinated control. In [18] uses the intelligent search technology of combining particle swarm optimization algorithm and genetic algorithm to automatically modify the parameters of power controller, and modify the system voltage by modifying the control mode of DG. In [19] and [20] are devoted to multi-objective reactive power optimization to obtain high-quality reactive power regulation strategies for distribution networks and restore the node voltage to the normal range. Although the aforementioned studies have made significant progress in voltage control using intelligent algorithms, several challenges remain when applied to the voltage optimization of distribution networks. Many methods perform well in static or single scenarios but lack the dynamic adaptability to the intense spatiotemporal variations in the output of small hydropower during its peak and low water periods. Moreover, traditional optimization strategies often treat each distributed power source as an independent entity, lacking a framework for collaborative optimization from the perspective of the entire cluster, leading to low control efficiency.

To ensure adaptive optimization of intelligent algorithm parameters and enhance algorithmic performance and accuracy, recent studies have employed fuzzy logic systems to dynamically control and adjust key parameters of metaheuristic algorithms such as genetic algorithms (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and flower pollination algorithm (FPA). For instance, in [21], a fuzzy logic-based parameter adaptation mechanism was proposed for FPA, utilizing two types of fuzzy inference systems to facilitate dynamic parameter adaptation in metaheuristic algorithms, thereby reducing uncertainty and improving performance. In [22], two shadow-type 2 fuzzy reasoning systems were developed for metaheuristic algorithms, demonstrating superior optimization results. Similarly, paper [23] introduced an interval type-2 fuzzy logic system (IT2FLS) for harmonic search (HS) and differential evolution (DE) algorithms, enabling dynamic parameter adjustment to enhance performance and minimize errors. In [24], a fuzzy tilted integral derivative (FTID) controller was designed by integrating the chicken swarm optimization (CSO) algorithm with a fuzzy logic system, achieving optimal parameter tuning and outperforming traditional PID controllers in both transient and steady-state responses. Additionally, paper [25] enhanced the HS algorithm by dynamically modifying its parameters using type-1 and interval type-2 fuzzy systems, confirming the effectiveness of fuzzy logic in improving metaheuristic algorithms. While these fuzzy logic-based methods exhibit strong nonlinear processing capabilities and robustness, their system designs tend to be relatively complex and computationally inefficient. In contrast, this paper adopts an intrinsic adaptive optimization mechanism within the algorithm, which is simpler, more efficient, and particularly suitable for real-time applications such as distribution network voltage control.

The overall goal of voltage balance control is to ensure power system voltage stability and power quality improvement through multi-dimensional, multi-measure coordination and optimization, while satisfying safety, economic, and reliability requirements. In order to solve the voltage problem caused by small hydropower cluster integration into distribution networks, this study takes the regional power grid data of small hydropower groups in the Meijiang River Basin and IEEE-33 node example data as the support in [26]-[27] and uses the improved particle swarm optimization algorithm with adaptive shrinkage factor (ASCF-PSO) to control the node voltage of distribution network in a safe and reasonable range. ASCF-PSO algorithm, which features a dynamically adaptive shrinkage factor. This improvement significantly enhances the convergence speed and global search capability compared to the standard PSO, effectively preventing premature convergence and ensuring solution quality. In order to minimize the node voltage fluctuation and regional network loss, the reactive power compensation device and the active and reactive power output of small hydropower units are combined to realize the comprehensive voltage control of low-voltage distribution network. At the same time, a clustering partitioning strategy based on electrical distance and reactive voltage sensitivity is proposed. This strategy can achieve coordinated voltage optimization control within the clusters. The effectiveness of the control strategy is verified by numerical simulation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the mathematical model of the power system and the formulation of the optimization problem. Section 3 elaborates on the proposed cluster division strategy and the ASCF-PSO based voltage optimization control framework. The content of the case study and result analysis, as well as the discussion, are presented in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future work.

2. System modeling

2.1. Power flow calculation of power system

Power flow calculation is essential for power system voltage optimization control. Changes in distribution network power flow affect the steady-state voltage distribution. Power flow calculation computes the state parameters of steady-state operation given the known power system topology, equipment parameters, and load parameters, ensuring system voltage control under normal operation. According to the power flow calculation formula, voltage fluctuation is related to active power , reactive power , resistance and reactance . The specific formulas for voltage deviation and active network loss between any two nodes are as follows:

where is the voltage deviation between nodes and . is the active network loss between nodes and . and are the active power of node and the reactive power of node respectively. and are the impedance values between nodes and . is the voltage amplitude of node .

Reasonable parameter adjustment can minimize voltage drop and regional network loss. According to the Newton-Raphson method, the basic data required for power flow calculation include branch resistance, reactance, susceptance, active and reactive power injected by small hydropower generators, node voltage, and node access load. Combining the voltage deviation and active network loss formulas yields the initial voltage of each distribution network node.

2.2. Constraints and objective function

The mathematical model with equality constraints for the power flow calculation equation of a certain node in the distribution network is:

where and represent the active and reactive power of node . and are the voltage amplitudes of node and node . represents the conductivity between nodes and . represents the electronegativity between nodes and . represents the voltage phase angle difference between two nodes.

The mathematical model for the equality constraint of power distribution network lines is:

where and represent the active and reactive power generated by the main generator in the distribution network. and provide active and reactive power to the distributed power source connected to node . , , , and respectively represent the active and reactive power absorbed by the load and the active and reactive power lost on the line.

The mathematical model of inequality constraints for controlling variables is as follows:

where and are the upper and lower limits of the reactive power compensation devices that are put into operation. , , , are the upper and lower limits of active and reactive power output of distributed power sources.

The mathematical model of inequality constraints for state variables is as follows:

where and are the upper and lower limits of the node voltage amplitude.

This study uses ASCF-PSO for distribution network voltage optimization, requiring the construction of a fitness function. The fitness function reflects the objective function value, constructed to minimize node voltage fluctuation and active area network loss. The objective function mathematical model is:

where is the objective function for the comprehensive optimization of active and reactive voltage of small hydropower. is the active power loss of the system. is the penalty coefficient for voltage exceeding the limit. is the square of the voltage deviation at node .

Constraints on the voltage deviation variable in the objective function ensure the node voltage is penalized when exceeding limits. The mathematical model is:

3. Voltage optimization control of small hydropower units connected to the distribution network

3.1. Voltage collaborative optimization control strategy

Distribution network voltage levels are maintained by controlling active and reactive power through generator sets, reactive power compensation devices, and other equipment. The ultimate goal of node voltage optimization is to minimize regional network losses and voltage fluctuations at each node while meeting power flow constraints, safety constraints, and other system constraints. Currently, most distribution networks achieve voltage regulation by combining reactive power compensation devices with DG units, focusing on selective optimization of specific grid stages or states. Ensuring the power factor remains within the normal range further adjusts the active output of distributed small hydropower.

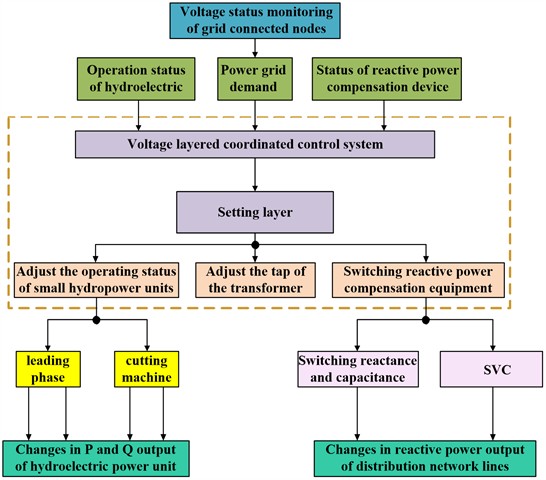

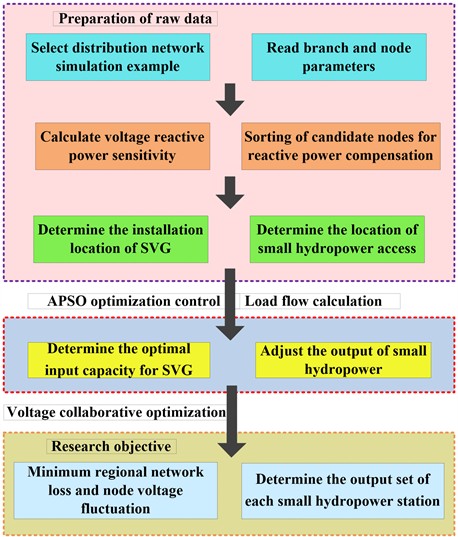

Fig. 1Small hydropower voltage collaborative optimization flow chart

The collaborative optimization process of active and reactive power voltage for small hydropower is shown in Fig. 1, indicating that multiple methods can be combined for voltage optimization. As shown in Fig. 1, the voltage of each node in the distribution network is first monitored. If it does not meet the demand of the power grid, priority is given to adjusting the operating status of small hydropower units and the switching capacity of reactive power compensation equipment through a voltage layered coordination control system. Adjusting the transformer tap is generally used as an auxiliary measure and is not easily changed. The phase in or phase out operation of small hydropower units will affect the overall active and reactive power output of the hydropower units, while changes in capacitance, reactance, and static var compensator (SVC) switching capacity will affect the flow of reactive power in the overall distribution network lines. Taking into account the output of small hydropower units and the switching level of reactive power compensation equipment in the distribution network can effectively achieve optimized control of node voltage.

3.2. Using reactive voltage sensitivity to determine the input of small hydropower

Unlike traditional distribution networks, distribution networks with high DG penetration exhibit complex, non-unidirectional power flow. The active and reactive power generated by distributed small hydropower units will be reversed back to the main network, potentially increasing the voltage of some nodes. Improper planning of small hydropower integration will significantly increase distribution network voltage control difficulty. In the distribution network, the reactive voltage sensitivity of each node can serve as a basis for small hydropower input. Calculating this sensitivity identifies weak system nodes. Higher sensitivity indicates greater node sensitivity to reactive power disturbances. Investing reactive power compensation equipment and small hydropower units in higher-sensitivity nodes enhances node voltage stability, facilitating voltage balance control within the cluster. Combined with the PSO intelligent optimization algorithm, it is easier to ensure distribution network voltage balance and stability throughout the entire period. Node voltage amplitude is primarily affected by injected reactive power flow. Ignoring the impact of active power flow, the simplified power flow equation is:

where is the change in reactive power flow. is the node admittance matrix. is the inverse of the voltage matrix. Since the matrix can be represented by the node admittance matrix, the reactive voltage sensitivity can be analyzed according to Eq. (9), and its mathematical expression is:

where is the reactive power sensitivity of node , which is the ratio of the voltage change at node to the reactive power flow change.

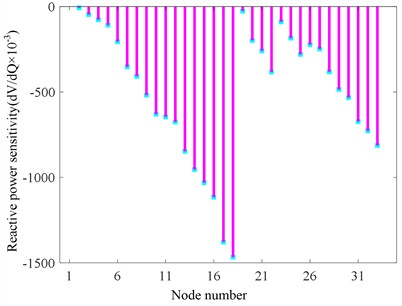

Fig. 2Reactive voltage sensitivity distribution of the IEEE-33 node system

This study selected the IEEE-33 node in the MATPOWER toolbox as an example, and calculated the reactive voltage sensitivity of each node according to the above formula. The reactive voltage sensitivity indicators of each node are shown in Fig. 2.

As shown in Fig. 2, the larger the absolute value of reactive voltage sensitivity, the more sensitive the node is to voltage changes. Selecting nodes with higher reactive power sensitivity to invest in distributed small hydropower and reactive power compensation devices has a significant effect on voltage optimization control. Select several sensitive nodes, namely 18, 17, 16, 15, 14, 13, 32, 31, and 22, as the basis for selecting the location of small hydropower and SVC for subsequent case analysis.

3.3. Division of small hydropower clusters

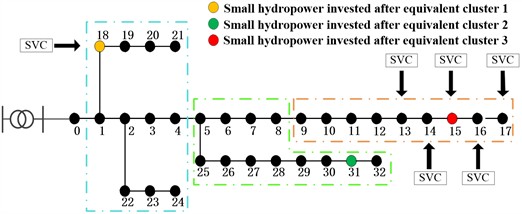

Reasonable division of small hydropower clusters can develop personalized voltage control strategies based on the voltage characteristics of each cluster, which helps optimize the active and reactive power allocation of distributed power sources, improve voltage control efficiency and accuracy, and enhance the grid's acceptance of small hydropower. This study uses the IEEE-33 node system as an example, determines the input node of small hydropower based on the reactive voltage sensitivity mentioned above, and selects SVC as the reactive power compensation device. A total of 9 small hydropower units and 6 SVC units are deployed in the distribution network. Small hydropower units are installed at nodes 13-18, 31-32, and 22, and SVC reactive power compensation devices are installed at nodes 13-18. The set SVC capacity is 0-500 KVar, with bidirectional reactive power regulation capability.

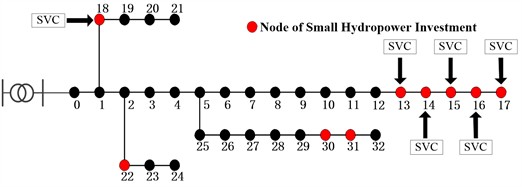

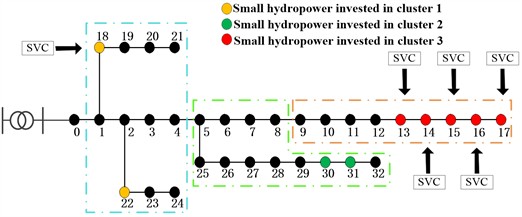

Fig. 3Distribution network system structure before and after cluster division

a) System structure before cluster partitioning

b) System structure after cluster partitioning

c) Equivalent system structure after cluster division

For the convenience of management and rational allocation of resources, the 9 small hydropower units deployed are divided into 3 clusters based on the electrical distance and topology structure of the IEEE-33 system, ensuring that small hydropower operates within each cluster and reducing power flow. In the subsequent voltage optimization control, the small hydropower within the cluster is equivalent to a node, reflecting the overall characteristics of the cluster. The system structure before and after cluster partitioning is shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 3(a) shows the input of small hydropower and reactive power compensation devices before the cluster division, Fig. 3(b) divides 9 small hydropower plants according to the topology of 33 nodes, and Fig. 3(c) is the equivalent diagram of each cluster, which equates the total output of small hydropower in the cluster to one node, which is convenient for calculation and analysis.

3.4. Voltage optimization control based on ASCF-PSO

Comprehensive voltage optimization control for distributed small hydropower is a nonlinear integer programming problem with multiple variables and constraints, requiring intelligent algorithms like PSO and GA for solution. Compared to other algorithms, PSO offers advantages such as fast convergence, simple principles, high computational efficiency, low parameter complexity, strong adaptability to continuous variables, and good dynamic robustness.

The particle swarm algorithm imitates the foraging behavior of bird flocks to find the global optimal solution. Including concepts such as particles, position, and velocity, the velocity and position are iteratively updated. During the iteration process, the fitness function is used to evaluate the quality of the results and update the optimal solution.

Set random solutions, initialize them, and find the optimal solution in the iteration. In each iteration, particles update their position by tracking two extremum values, namely the particle’s own optimal solution and the entire population’s optimal solution . Search for the target in -dimensional space, where parameter is the total number of optimization variables. Each particle has its own position vector and velocity vector at a certain moment, expressed as:

where and represent the position and velocity of the variable in dimensional space.

In the process of seeking the optimal solution, particles update their position and velocity at time . The expressions for the position update formula and velocity update formula are:

where is the position of the particle at time in a certain dimension, representing the sum of the particle position at time 1 and the particle velocity at time 1. is the velocity of a particle at a certain one-dimensional time . is the inertia weight factor. is the individual learning factor, is the social learning factor. and are random numbers between [0, 1]. is the individual’s known optimal solution. is the best-known optimal solution for the population. The velocity of particles at time consists of three parts: inertia, cognition, and society. Reasonable parameter settings are beneficial for solving the optimal value.

Standard PSO suffers from premature convergence, local optima, and low search efficiency in voltage optimization. To address these issues, this study uses ASCF-PSO for voltage optimization control. The number of iterations and population size were set to 50. This setting is a common practice when dealing with optimization problems of power systems of similar scale. To achieve a more balanced ability of global and local particle search, a dynamic adaptive linear decay shrinkage factor was constructed, and its calculation formula is:

where and are the maximum and minimum values of , the maximum number of iterations is , and the number of iterations is . The higher the initial value, the more conducive it is to exploration, while its linear decrease helps to conduct more detailed development around the optimal solution.

Construct an expression for the dynamic contraction factor , and its calculation formula is:

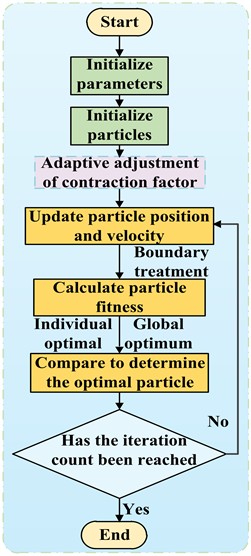

where is the sum of and , usually greater than 4, and the value range of is kept between [0.4, 0.9] to ensure convergence and balance global exploration and local development. These parameter values are derived based on preliminary simulations, and the simulation results show a good balance achieved between computation time and solution quality. Replace the inertia weight factor with the dynamic contraction factor , and achieve this by dynamically adjusting and during the iteration process. The process of the ASCF-PSO algorithm is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4Flowchart of the ASCF-PSO algorithm

ASCF-PSO offers fast convergence, more accurate optimal solution search, high robustness, and strict boundary control, suiting complex multimodal function optimization problems. Compared to basic PSO, it is more conducive to solving distribution network node voltage optimization control. Based on this, selecting appropriate distribution network examples and nodes for small hydropower units allows voltage optimization for the optimal node voltage solution. The overall voltage optimization control process framework is shown in Fig. 5.

As shown in Fig. 5, the process is: first, select a suitable distribution network example to obtain raw data like node reactive power and voltage sensitivity to determine SVC and small hydropower connection positions. Then, calculate node voltage amplitude through power flow calculation and perform ASCF-PSO voltage optimization control on nodes exceeding limits. Finally, obtain the optimal SVC input capacity and each hydropower cluster's output through algorithm optimization to meet the goal of minimizing regional network loss and node voltage limit.

Fig. 5Overall framework of voltage optimization control

4. Case studies and discussion

4.1. Raw data analysis

Based on the above research and analysis, the voltage balance control of the distribution network is carried out by combining the SVC reactive power compensation device with the different active and reactive power outputs of small hydropower in the two spatiotemporal backgrounds of high and low water periods. The original data comes from the output of 9 small hydropower units in the Meijiang River Basin of Guizhou Province. By comprehensively adjusting the voltage values of each node in the power grid through multiple control variables, it is ensured that the node voltage does not exceed the limit. The normal range of voltage is set between 0.95-1.05, expressed in unit value form. The IEEE-33 node distribution system data from the MATPOWER toolbox is used as the simulation standard data. The reference voltage at the head end of the power network is 10.5 kV, the reference capacity is 10 MVA, and the total system load is 5084.26+j2547.32 kVA. The network has one main generator located at node 0, defined as the balancing node, and the other nodes are treated as PQ nodes.

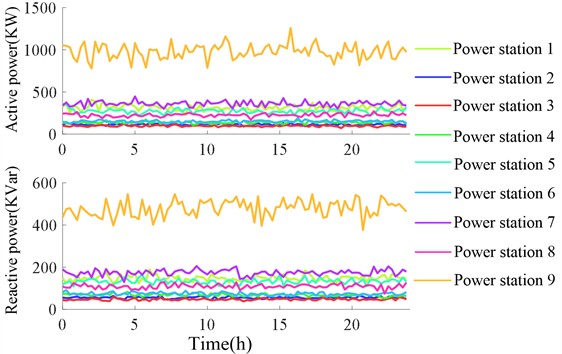

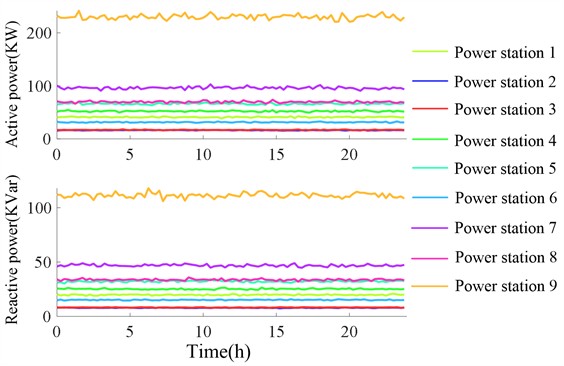

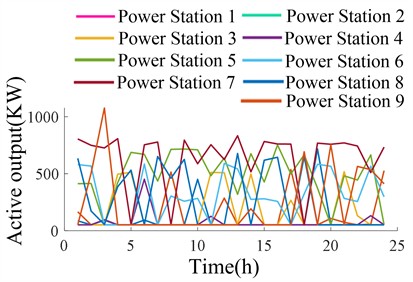

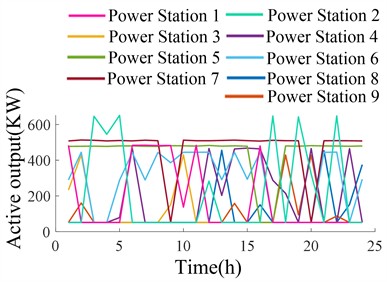

There is a significant difference in average active and reactive power output between wet and dry seasons. The initial daily average output is shown in Table 1. Based on this, the injection power of small hydropower can be obtained. Connecting to the distribution network changes the initial power flow distribution. Predicting changes within a day based on average daily output, monitored every 15 minutes, the active and reactive power output curves for each small hydropower in wet and dry seasons are simulated, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7.

According to the curves, output fluctuates greatly in the wet season due to significantly increased rainfall and river inflow, with precipitation uncertainty and unevenness causing sharp short-term inflow changes. In the dry season, inflow is relatively stable, making output regulation easier.

Table 1Average daily active and reactive output of small hydropower stations

Number | Name | Average active power during flood season (KW) | Average active power during dry season (KW) | Mean reactive power during flood season (KVar) | Mean reactive power during dry season (KVar) |

1 | Meijiang reservoir power station | 309.53 | 41.13 | 150.0 | 19.9 |

2 | Walnut dam power station | 113.48 | 16.35 | 55.0 | 7.9 |

3 | Xuantang power station | 97.43 | 16.95 | 47.2 | 8.2 |

4 | Shiyan power station | 137.40 | 52.16 | 66.5 | 25.3 |

5 | Daping power station | 272.34 | 66.39 | 131.9 | 32.2 |

6 | Yankongba power station | 150.30 | 31.43 | 72.8 | 15.2 |

7 | Jiangjiaba power station | 360.14 | 96.30 | 174.5 | 46.7 |

8 | Dyeing vat power station | 223.92 | 69.76 | 108.5 | 33.8 |

9 | Wuyi power station | 972.3 | 230.06 | 471.1 | 111.5 |

Fig. 6Average daily active and reactive output curve of small hydropower in wet season

Fig. 7Average daily active and reactive output curve of small hydropower in dry season

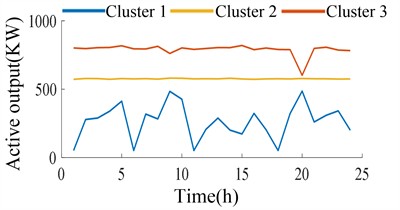

4.2. Analysis of voltage optimization control

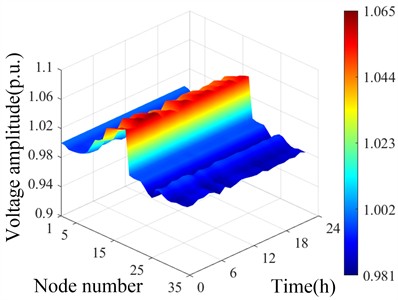

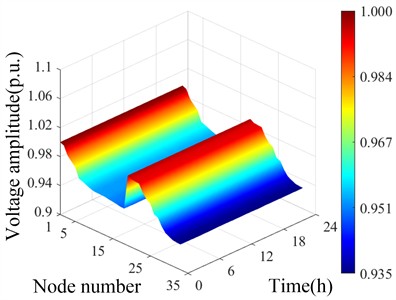

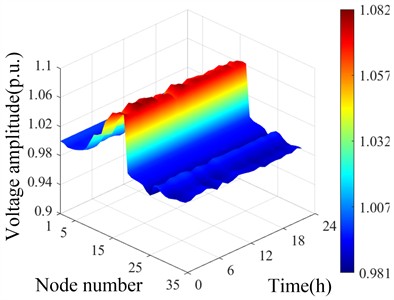

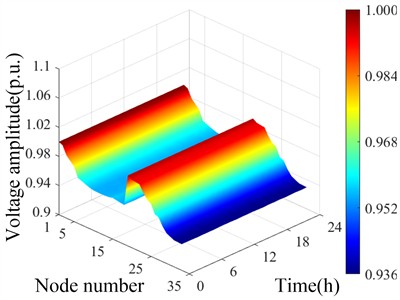

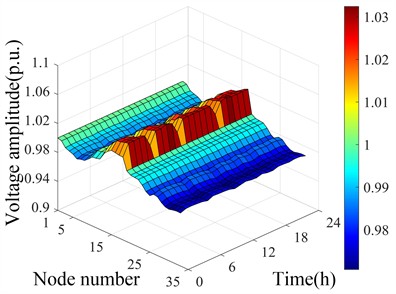

On the initial active and reactive power output curves during the wet and dry seasons, hourly output data were selected for a total of 24 datasets to obtain the spatiotemporal distribution of voltage 24 hours after connecting to DG during the wet and dry seasons. According to Fig. 3, the 9 small hydropower plants were clustered and divided into 3 clusters. Equivalent calculations were conducted within each cluster to obtain the spatiotemporal distribution of 24-hour voltage during the wet and dry seasons. As shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8Spatial and temporal distribution of initial voltage of distribution network before and after cluster division

a) Temporal and spatial distribution of voltage during the flood season before cluster division

b) Temporal and spatial distribution of voltage during the dry season before cluster division

c) Temporal and spatial distribution of voltage during the flood season after cluster division

d) Temporal and spatial distribution of voltage during the dry season after cluster division

Fig. 8(a) and 8(b) show that the output of each small hydropower unit is relatively high during the flood season, resulting in some nodes exceeding the upper limit of voltage, with the maximum amplitude of voltage exceeding the limit at nodes 16-18. During the dry season, the output of small hydropower units is relatively low, and even stops at some point. Therefore, the voltage at some nodes decreases below the lower limit, and the voltage at nodes 27-32 at the end of the distribution network decreases to the maximum extent. Fig. 8(c) and 8(d) show that after cluster partitioning, due to the equivalence of several adjacent small hydropower stations within the cluster at one node, the voltage amplitude of some nodes increases significantly during the wet season, while the change is not significant during the dry season.

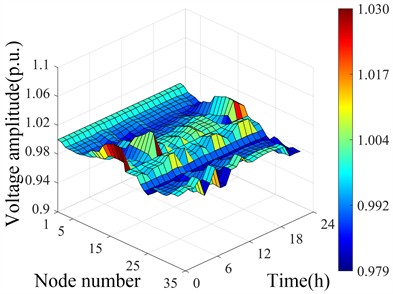

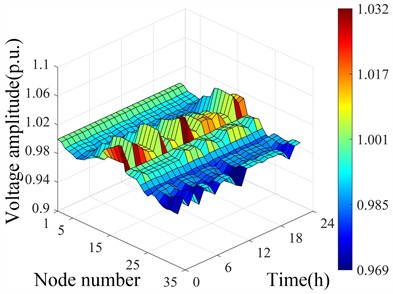

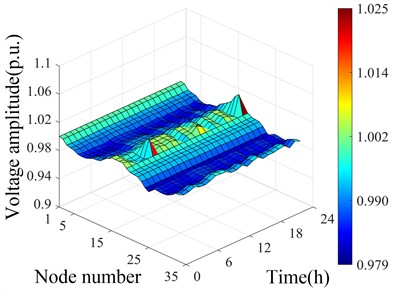

To ensure all node voltages remain within the normal range, ASCF-PSO regulates small hydropower output and SVC reactive power input for optimization. The optimized voltage distribution under different scenarios before and after cluster division is shown in Fig. 9. Fig. 9(a) and 9(b) show that after optimization, all voltages are within 0.95-1.05 during both seasons, with max 1.03 and min 0.979 p.u. Fig. 9(c) and 9(d) show that after cluster partitioning, ASCF-PSO still ensures no limit violations, enabling coordinated scheduling and power allocation within clusters, reducing power flow.

Fig. 9Spatiotemporal distribution of voltage under different scenarios after ASCF-PSO optimization

a) Optimized spatiotemporal distribution of voltage during flood season

b) Optimized spatiotemporal distribution of voltage during dry season

c) Optimization of cluster partitioning and spatiotemporal distribution of voltage during flood season

d) Spatiotemporal distribution of voltage during dry season after cluster partitioning optimization

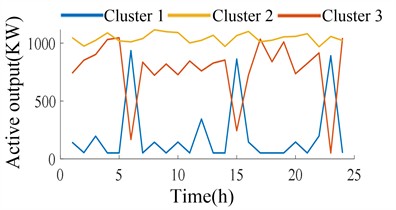

Fig. 10(a) and 10(b) show the active power output of 9 small hydropower plants after optimization. The power factor is set to 0.9, and the objective function of ASCF-PSO optimization ensures the minimum regional network loss and node voltage fluctuation. However, the output fluctuation of small hydropower plants within 24 hours is large, with large power flow and disorder, which does not conform to the overall scheduling strategy of the distribution network for small hydropower plants. Fig. 10(c) and 10(d) show the active power output of small hydropower at different periods after cluster division, with the power factor still set at 0.9. It can be clearly seen that the fluctuation of active power output of small hydropower has decreased after cluster division, especially in Cluster 2, which is more in line with the actual scenario of small hydropower output adjustment. Cluster division of small hydropower optimizes the allocation of water resources, with centralized distribution of output among various hydropower units and coordinated output, and has practical significance.

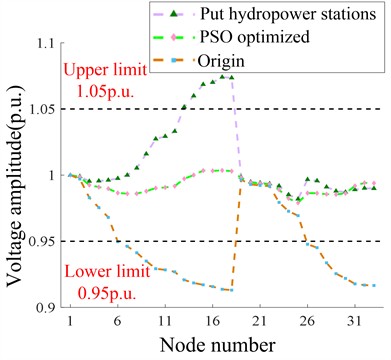

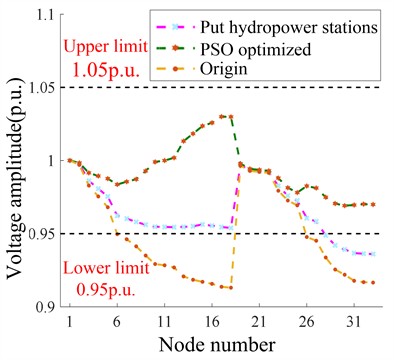

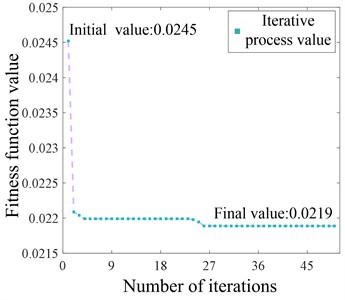

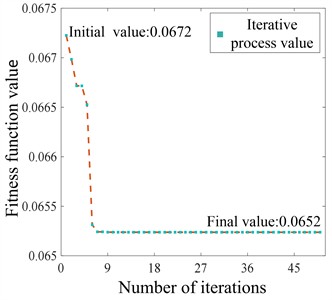

Taking ASCF-PSO voltage optimization control at a certain time in wet and dry seasons after cluster division as an example, the optimization effect and fitness function value changes are more intuitively demonstrated in Fig. 11. Fig. 11(a) and 11(b) show the voltage optimization effect at each node at a certain time. During both seasons, the algorithm maintains voltages within the normal range. Fig. 11(c) and 11(d) show that after 50 iterations, the fitness function values combining minimum loss and fluctuation achieve the optimal solution..

Fig. 10Active power output of small hydropower under different scenarios after ASCF-PSO optimization

a) Optimized active output of small hydropower during flood season

b) Optimized active output of small hydropower during dry season

c) Optimized cluster partitioning for active power output of small hydropower during the flood season

d) Active output of small hydropower during dry season after cluster partitioning optimization

At this point, each node's voltage is optimized by ASCF-PSO, preventing limit violations. The optimized SVC capacity and each cluster's active/reactive power output data can be obtained. The optimal SVC input capacity and output are shown in Tables 2 and 3. SVC provides inductive reactive power in the wet season and capacitive in the dry season. Comprehensively adjusting SVC capacity and cluster output prevents node voltage limit violations, ensuring line safe operation.

Table 2Optimal SVC injection capacity at a certain time in wet season and dry season

Node number | Wet season | Dry season |

Input capacity (KVar) | Input capacity (KVar) | |

13 | 59 | 3.4 |

14 | 268 | 36 |

15 | 97 | 402 |

16 | 111 | 265 |

17 | 24 | 500 |

18 | 0 | 500 |

Table 3Optimal small hydropower output of each cluster at a certain time in wet season and dry season

Wet season | Dry season | |||

Cluster number | Active output (KW) | Reactive power output (KVar) | Active output (KW) | Reactive power output (KVar) |

1 | 208.24 | 100.85 | 387.27 | 185.14 |

2 | 797.8 | 386.4 | 694 | 336.6 |

3 | 1045.4 | 506.3 | 472.4 | 228.8 |

Fig. 11Distribution network node voltage optimization effect and fitness function value

a) Optimization of voltage during the flood season after cluster partitioning

b) Optimization of voltage during dry season after cluster partitioning

c) The fitness function value optimized during the flood season

d) The fitness function value optimized during the dry season

4.3. Discussion

The results demonstrated in Fig. 9 and Fig. 11 are not merely numerical simulations, they have profound practical implications. The proposed ASCF-PSO strategy can be deployed in the energy management system (EMS) of distribution networks to perform real-time or day-ahead voltage stability control. It is particularly crucial for smart grids with high penetration of renewables, where voltage fluctuations are becoming increasingly common. By ensuring voltage security, this method directly contributes to reducing the risk of equipment damage and improving power supply reliability for end-users.

Despite the promising results, several limitations should be acknowledged. This study is based on a 33-node system. The computational efficiency and effectiveness of this method in larger-scale distribution networks need further verification. The computational time of ASCF-PSO may still be a challenge for real-time control applications. The performance of the algorithm depends to a certain extent on the scenario settings, and its universality in distribution networks with different climatic conditions and different watershed characteristics needs more cases to verify.

Future research will focus on the following directions. The framework will be extended to larger scales and real-world distribution networks to comprehensively test its scalability and robustness. More advanced machine learning techniques will be explored to predict the temporal and spatial output of hydropower, which will further enhance the active control capability of the proposed strategies. Combine small hydropower with other renewable energy sources to form a hybrid renewable energy system, and coordinate with each other to achieve voltage optimization.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the voltage over-limit issue of distribution networks integrated with small hydropower clusters under different spatiotemporal scenarios. The main contributions are as follows:

1) A novel optimization framework was established, which innovatively combines the ASCF-PSO algorithm with a cluster division strategy. This framework is specifically designed to handle the spatiotemporal variability inherent in small hydropower generation.

2) The proposed ASCF-PSO algorithm demonstrated superior performance, effectively minimizing both node voltage fluctuations and network losses while ensuring all voltages remain within safe limits under both wet and dry season scenarios.

3) The cluster-based optimization strategy proved to be not only effective for voltage control but also beneficial for practical grid operation. It resulted in more coordinated and smoother power output from the hydropower plants, enhancing dispatch efficiency and reducing unnecessary power flow fluctuations.

There are still some limitations and future research directions need to be considered. The method was verified on a standard test system; its scalability and computational efficiency in larger, more realistic networks need further study. The optimization relies on accurate hydropower output prediction, which can be uncertain. Future work will focus on integrating uncertainty quantification techniques to enhance strategy resilience against prediction errors and on extending the approach to hybrid renewable energy systems. The findings and proposed framework provide a reliable and effective solution for enhancing voltage stability in distribution networks with high intermittent renewable penetration.

References

-

Z. X. Zhang, M. J., Cui, and C. B. Zhang, “Active and reactive power coordinated optimal voltage control of a distribution network based on counterfactual multi-agent reinforcement learning,” (in Chinese), Power System Protection and Control, Vol. 52, No. 18, pp. 76–86, 2024, https://doi.org/10.19783/j.cnki.pspc.231477

-

S. H. Lee, D. Choi, and J.-W. Park, “Power-sensitivities-based indirect voltage control of renewable energy generators with power constraints,” IEEE Access, Vol. 9, pp. 101655–101664, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2021.3097350

-

Y. Qiu, J. Lin, F. Liu, Y. Song, G. Chen, and L. Ding, “Stochastic online generation control of cascaded run-of-the-river hydropower for mitigating solar power volatility,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, Vol. 35, No. 6, pp. 4709–4722, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrs.2020.2991229

-

Z. Cheng, L. Wang, S. Zeng, C. Su, R. Zhang, and W. Zhou, “Partition-global dual-layer collaborative voltage control strategy for active distribution network with high proportion of renewable energy,” IEEE Access, Vol. 12, pp. 22546–22556, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3364543

-

A. Fu, M. Cvetkovic, and P. Palensky, “Distributed cooperation for voltage regulation in future distribution networks,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, Vol. 13, No. 6, pp. 4483–4493, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2022.3191389

-

M. M. Othman, M. H. Ahmed, and M. M. A. Salama, “A coordinated real-time voltage control approach for increasing the penetration of distributed generation,” IEEE Systems Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 699–707, Mar. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/jsyst.2019.2904532

-

Y. Luo, Q. Nie, D. Yang, and B. Zhou, “Robust optimal operation of active distribution network based on minimum confidence interval of distributed energy beta distribution,” Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 423–430, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.35833/mpce.2020.000198

-

A. Elmitwally, M. Elsaid, M. Elgamal, and Z. Chen, “A fuzzy-multiagent self-healing scheme for a distribution system with distributed generations,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 2612–2622, Sep. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrs.2014.2366072

-

M. V. Gururaj and N. P. Padhy, “A novel decentralized coordinated voltage control scheme for distribution system with DC microgrid,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp. 1962–1973, May 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/tii.2017.2765401

-

M. Yousif, Q. Ai, Y. Gao, W. A. Wattoo, Z. Jiang, and R. Hao, “An optimal dispatch strategy for distributed microgrids using PSO,” CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 724–734, Jun. 2019, https://doi.org/10.17775/cseejpes.2018.01070

-

B. Gao, C. Peng, and W. M. Lu, “Reactive power and voltage control of power grid system based on improved particle swarm algorithm,” (in Chinese), Computer simulation, Vol. 39, No. 9, pp. 86–90, 2022.

-

X. Wu et al., “Reactive power and voltage control based on improved particle swarm optimization in power system,” (in Chinese), 8th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation (WCICA 2010), Vol. 35, No. 21, pp. 5291–5295, Jul. 2010, https://doi.org/10.1109/wcica.2010.5554836

-

A. Abessi, V. Vahidinasab, and M. S. Ghazizadeh, “Centralized support distributed voltage control by using end-users as reactive power support,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 178–188, Jan. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2015.2410780

-

J. Liao, J. Lin, G. Wu, and S. Lai, “Collaborative optimization planning method for distribution network considering “hydropower, photovoltaic, storage, and charging”,” IEEE Access, Vol. 12, pp. 172115–172124, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3487996

-

X. Li, L. Wang, N. Yan, and R. Ma, “Cooperative dispatch of distributed energy storage in distribution network with PV generation systems,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity, Vol. 31, No. 8, pp. 1–4, Nov. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/tasc.2021.3117750

-

L. Chen, Z. Deng, and X. Xu, “Two-stage dynamic reactive power dispatch strategy in distribution network considering the reactive power regulation of distributed generations,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 1021–1032, Mar. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrs.2018.2875032

-

Y. Huo et al., “Data-driven predictive voltage control for distributed energy storage in active distribution networks,” CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems, Vol. 10, No. 5, pp. 1876–1886, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.17775/cseejpes.2022.02880

-

M. Dashtdar et al., “Improving the power quality of island microgrid with voltage and frequency control based on a hybrid genetic algorithm and PSO,” IEEE Access, Vol. 10, pp. 105352–105365, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2022.3201819

-

R. Wu and S. Liu, “Multi-objective optimization for distribution network reconfiguration with reactive power optimization of new energy and EVs,” IEEE Access, Vol. 11, pp. 10664–10674, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2023.3241228

-

X. Liu, P. Zhang, H. Fang, and Y. Zhou, “Multi-objective reactive power optimization based on improved particle swarm optimization with ε-greedy strategy and pareto archive algorithm,” IEEE Access, Vol. 9, pp. 65650–65659, Jan. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2021.3075777

-

H. R. Patel and V. A. Shah, “Type-2 fuzzy logic applications designed for active parameter adaptation in metaheuristic algorithm for fuzzy fault-tolerant controller,” International Journal of Intelligent Computing and Cybernetics, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 198–222, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1108/ijicc-01-2022-0011

-

H. R. Patel and V. A. Shah, “Shadowed type-2 fuzzy sets in dynamic parameter adaption in Cuckoo search and flower pollination algorithms for optimal design of fuzzy fault-tolerant controllers,” Mathematical and Computational Applications, Vol. 27, No. 6, p. 89, Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/mca27060089

-

H. R. Patel and V. A. Shah, “simulation and comparison between fuzzy harmonic search and differential evolution algorithm: type-2 fuzzy approach,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, Vol. 55, No. 16, pp. 412–417, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.09.059

-

H. R. Patel, “Optimal intelligent fuzzy TID controller for an uncertain level process with actuator and system faults: Population-based metaheuristic approach,” Franklin Open, Vol. 4, p. 100038, Sep. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fraope.2023.100038

-

H. R. Patel and V. A. Shah, “Comparative analysis between two fuzzy variants of harmonic search algorithm: fuzzy fault tolerant control application,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, Vol. 55, No. 7, pp. 507–512, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.07.494

-

M. E. Baran and F. F. Wu, “Network reconfiguration in distribution systems for loss reduction and load balancing,” IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 1401–1407, Apr. 1989, https://doi.org/10.1109/61.25627

-

S. H. Dolatabadi, M. Ghorbanian, P. Siano, and N. D. Hatziargyriou, “An enhanced IEEE 33 bus benchmark test system for distribution system studies,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 2565–2572, May 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrs.2020.3038030

About this article

Project Supported by China Southern Power Grid Co., Ltd. Technology Project (No. GZKJXM20232577).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Tinghao Ren: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft preparation. Qican Dai: formal analysis, investigation, software, writing-review and editing. Jun Cai: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervisor. Yiming Fan: methodology, validation, writing-review and editing. YiZhao Bao: methodology, validation, writing-review and editing. Ying Lu: data curation, formal analysis, validation.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.