Abstract

Shotcrete has the problems of easy cracking and high brittleness, the incorporation of fiber can reduce the brittleness and improve the mechanical properties and durability of shotcrete. This study investigated the effect of basalt fibers (BF) lengths on mechanical properties and durability of shotcrete. The BFs were also compared with steel fibers (SF) to verify the performance advantages of BFs. The results showed that 16 mm BF had the best effect on enhancing the mechanical properties of shotcrete. The 16 mm BF shotcrete had the best frost resistance, while the 50 mm BF had poor frost resistance. The SF reinforced shotcrete exhibits inferior frost resistance compared to BF reinforced shotcrete, due to its narrower operating temperature range and higher susceptibility to corrosion.

1. Introduction

Shotcrete has become a widely used cementitious material in underground engineering and slope protection construction due to its short setting time, easy operation and high early strength [1-2]. As a core aspect of safe construction of transport projects, the immediate support effect of shotcrete is a decisive factor in controlling the deformation of the surrounding rock and ensuring the progress of the project. Similar to conventional cast-in-place concrete, shotcrete is prone to cracking and high brittleness, which compromises durability and reduces structural service life [3]. The incorporation of fibers into shotcrete has been shown to enhance strength and durability while reducing material brittleness [4].

Currently, the most commonly used fibers in shotcrete applications include steel fiber (SF), basalt fiber (BF), and polypropylene (PP) fiber [5-6]. The addition of SF has been demonstrated to enhance the mechanical properties of concrete [7]. Zhang et al. [8] found the higher dosage of SF leads to more effective suppression of microcrack development within the concrete. However, SF are susceptible to corrosion in concrete [9]. In comparison, PP fibers exhibit excellent corrosion resistance but demonstrate relatively weak adhesion to the concrete substrate [10].

The BF is produced from natural basalt ore through a process involving raw material crushing, high-temperature melting at 1450 °C-1500 °C, and continuous filament drawing through platinum-rhodium alloy bushings [11-12]. BF exhibits outstanding mechanical properties and exceptional temperature adaptability [13-15]. Qin and Wu [16] studied the effect of BF content and length on concrete properties, identifying optimal parameters as 1.5-2.0 kg/m3in dosage and 18-24 mm in length. The addition of BF refines the internal pore structure of concrete, reduces microcrack formation, and enhances structural compactness. Elshazli et al. [17] illustrated that the BF improved both mechanical properties and durability properties of concrete, with a volume fraction of 0.3 % providing an optimal balance between mechanical enhancement and corrosion resistance. Li et al. [18] compared the performance of alkali-resistant BFs (ABF) and conventional BF, finding that ABF exhibits superior bonding with the concrete matrix. At a dosage of 0.1 %, ABF increased compressive strength, flexural strength, and splitting tensile strength by 2.5 %, 17.2 % and 12.1 %, respectively. These findings collectively establish BF as an effective reinforcement material for enhancing the mechanical and durability properties of shotcrete.

In order to solve the problems of lack of toughness and durability of shotcrete, BFs are used to strengthen the shotcrete. In this work, the influence of different lengths of BF on the mechanical properties and durability properties of shotcrete is investigated. Meanwhile, SF were set as a control group to verify the performance advantages of BF.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

In this test, the grade of shotcrete was configured as C30. Both the coarse aggregates (nominal size: 5-12 mm) and the fine aggregates (natural river sand with a fineness modulus of 2.6) were employed. The length of SF is 25 mm. The admixtures include a high-range water reducer and an alkali-free liquid flash setting admixture.

2.2. Proportioning of shotcrete

The shotcrete mix proportions are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The dosage of water reducing admixture (WRA) and flash setting admixture (FSA) is 5.5 and 33.6 kg/m3, respectively.

Table 1The Basic mix proportion of shotcrete (kg/m3)

P·O 42.5 | silica fume | Sand | Stone | Water | WRA | FSA |

399 | 21 | 784 | 958 | 187 | 5.5 | 33.6 |

Table 2The mix proportion of each group (kg/m3)

Group | P·O 42.5 | silica fume | Sand | Stone | Water | SF | BF |

NF | 399 | 21 | 958 | 784 | 187 | 0 | 0 |

SF | 399 | 21 | 958 | 784 | 187 | 35 | 0 |

BF-6 | 399 | 21 | 958 | 784 | 187 | 0 | 4 |

BF-16 | 399 | 21 | 958 | 784 | 187 | 0 | 4 |

BF-50 | 399 | 21 | 958 | 784 | 187 | 0 | 4 |

Note. Abbreviations: NF, non-fiber reinforced; SF, steel fiber reinforced; BF-6, 6 mm basalt fiber reinforced; BF-16, 16 mm basalt fiber reinforced; BF-50, 50 mm basalt fiber reinforced | |||||||

2.3. Test methods

The specimens used in this test were made from shotcrete slabs cut and cured to a specified age for testing. Cubic specimens measuring 100×100×100 mm were fabricated in accordance with GB/T 50081-2019 and tested for compressive strength and splitting tensile strength (Fig. 1). The compressive strength and splitting strength results were averaged from three specimens.

Fig. 1Splitting strength test (Hanghang Wang took the photo, Chang’an University, and 2025.06.03)

The compressive strength and splitting tensile strength are calculated according to Eqs. (1, 2):

where denotes the failure load of the specimen, and denotes the loaded area of the specimen.

The rapid freeze-thaw test was conducted in accordance with GB/T 50082-2024, and the performance was evaluated by the mass loss rate and the relative dynamic elastic modulus. The mass loss rate and relative dynamic elastic modulus results were averaged from three specimens.

The mass loss rate is one of the most important characterization indicators of concrete's own frost durability, and the mass loss rate is calculated according to Eq. (3):

where denotes the mass loss rate of specimens after freeze-thaw cycles, denotes the quality of specimens before freeze-thaw cycles, and denotes the mass of specimen after freeze-thaw cycles.

The dynamic modulus of elasticity of concrete reflects the compactness of its internal structure, and higher values indicate greater structural density. The relative dynamic modulus is calculated according to Eq. (4):

where denotes the relative dynamic modulus of elasticity of specimens after freeze-thaw cycles, denotes the transverse fundamental frequency of specimens after freeze-thaw cycles, and denotes the transverse fundamental frequency of specimen before n freeze-thaw cycles.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Compressive strength

The compressive strength enhancement factor was calculated according to Eq. (5):

where denotes the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced shotcrete, denotes the compressive strength of ordinary shotcrete.

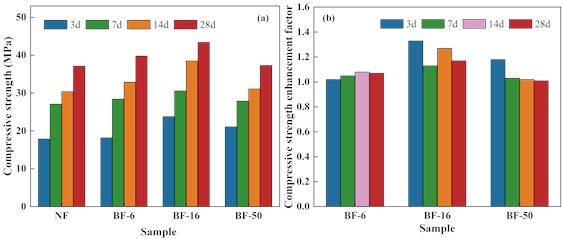

As indicated in Fig. 2, the compressive strength of shotcrete peaks at a 6 mm fiber length across all curing ages. At a fiber length of 16 mm (BF-16), the 28 d compressive strength reaches 43 MPa, representing a 16.2 % improvement over plain shotcrete. This enhancement is attributed to the denser internal structure through BF incorporation, which improves crack resistance. However, when the BF length increases to 50 mm (BF-50), the 28 d compressive strength decreases due to fiber agglomeration caused by inadequate dispersion within the matrix.

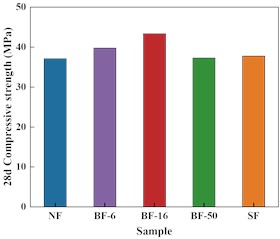

According to Fig. 3, SF also enhance the compressive strength of the shotcrete, achieving a 28 d value of 38 MPa. Nevertheless, this represents an 11.6 % reduction compared to the BF-16 group, indicating that SF provides a relatively weaker enhancement effect on compressive strength. The high stiffness of steel fibers makes them prone to balling and non-uniform dispersion during the mixing process, may result the lower compressive strength.

Fig. 2Effect of BF length on compressive strength (NF, non-fiber reinforced; SF, steel fiber reinforced; BF-6, 6 mm basalt fiber reinforced; BF-16, 16 mm basalt fiber reinforced; BF-50, 50 mm basalt fiber reinforced)

Fig. 3Effect of fiber type on 28d compressive strength

3.2. Splitting tensile strength

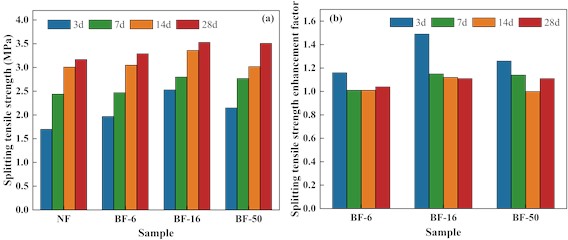

The variation of splitting tensile strength with fiber length is presented in Fig. 4. The splitting strength similarly follows a trend of initial increase followed by decrease. The optimum BF length of 16 mm yields a 28 d splitting tensile strength of 3.5 MPa, corresponding to a 9.4 % improvement over the reference shotcrete. This improvement stems from the appropriate fiber length enhancing matrix connectivity and utilizing the inherent tensile properties of the fibers. However, the splitting strength decreased at 50 mm BF length (BF-50), confirming that excessive fiber length diminishes the reinforcement effect.

Fig. 4Effect of BF length on splitting tensile strength

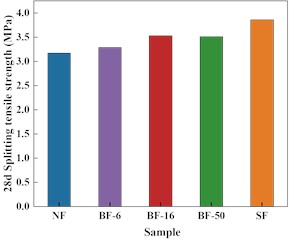

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the SF exhibit the most pronounced enhancement in splitting tensile strength, achieving a 28 d value of 3.9 MPa. This represents a 21.9 % improvement over plain shotcrete, indicating that SF provides superior enhancement compared to BF fibers for this particular mechanical property. This is likely due to the high elastic modulus and excellent anchorage performance of SFs, which enhance the crack resistance of shotcrete, thereby resulting in higher splitting tensile strength.

In summary, BFs significantly enhance the early splitting tensile strength of shotcrete, with 16mm fibers demonstrating optimal performance. However, SFs also exhibit substantial improvement in splitting tensile strength under standardized curing conditions.

Fig. 5Effect of fiber on 28d splitting tensile strength

3.3. Frost resistance

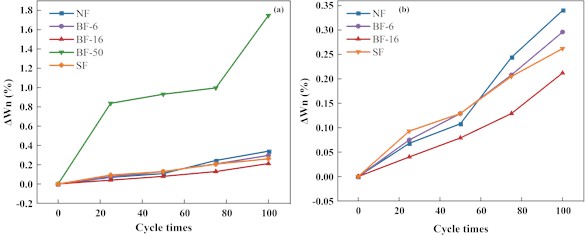

3.3.1. Rate of mass change

As illustrated in Fig. 6, a progressive rise in mass loss rate is observed with increasing freeze-thaw cycles. Notably, 50 mm BFs exacerbate mass loss during freeze-thaw cycles. Specimens containing 50 mm fibers exhibited dramatically higher mass loss – approximately 12 times and 5 times greater than conventional shotcrete after 25 and 100 cycles, respectively. This detrimental effect is attributed to the excessively high aspect ratio, which creates extensive interfacial contact areas with the shotcrete matrix. These interfaces possess relatively lower strength compared to both the concrete bulk material and the fibers themselves, rendering them particularly vulnerable to freeze-thaw damage. In contrast, 16mm BFs effectively reduce mass loss compared to ordinary shotcrete, demonstrating their potential for enhancing frost resistance in shotcrete applications.

Fig. 6Effect of BF on rate of mass change

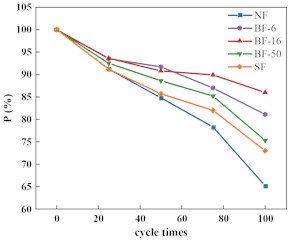

3.3.2. Relative dynamic modulus of elasticity

As shown in Fig. 7, the relative dynamic modulus exhibited a clear negative correlation with the number of freeze-thaw cycles, demonstrating accelerated material deterioration. When the number of cycles reaches 50, initial damage emerges within the concrete matrix, activating the reinforcement mechanisms of both basalt and steel fibers. The 6 mm BFs (BF-6), with their low length-to-diameter ratio, effectively suppress microcrack initiation during early freeze-thaw stages. The 16 mm and 50 mm basalt fibers demonstrate intermediate effectiveness, while steel fibers show the least improvement. Beyond 50 cycles, 16 mm BFs deliver optimal performance, increasing the relative dynamic elastic modulus by 32 % compared to ordinary shotcrete after 100 freeze-thaw cycles. Although both BF types enhance the dynamic modulus, SF provides inferior reinforcement due to corrosion susceptibility and limited operating temperature range. In summary, 16 mm BF significantly enhance concrete frost resistance, supporting enhanced durability for concrete in cold regions of northern China.

Fig. 7Effect of BF on relative dynamic modulus of elasticity

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the effect of BF on shotcrete is investigated and compared with SF. The results are as follows.

1) BF effectively enhance both compressive and splitting tensile strength of shotcrete, with varying lengths exhibiting distinct performance advantages at different curing ages, demonstrating length-dependent activation periods.

2) The 16 mm BF provides optimal mechanical enhancement, significantly enhancing the compressive and splitting tensile strength, while 6 mm BF demonstrate superior early-age splitting tensile strength development.

3) BFs outperform SFs in controlling mass loss and maintaining dynamic elastic modulus during freeze-thaw exposure. The 16 mm length shows overall best performance, whereas 6 mm BF effective preserve modulus at low cycle numbers. SFs exhibit inferior frost resistance compared to BF, primarily due to their limited operational temperature limitations and corrosion vulnerability.

References

-

T. Asheghi Mehmandari, M. Shokouhian, M. Imani, and A. Fahimifar, “Experimental and numerical analysis of tunnel primary support using recycled, and hybrid fiber reinforced shotcrete,” Structures, Vol. 63, p. 106282, May 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106282

-

S. Guler, B. Öker, and Z. F. Akbulut, “Workability, strength and toughness properties of different types of fiber-reinforced wet-mix shotcrete,” Structures, Vol. 31, pp. 781–791, Jun. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.02.031

-

G. Liu, W. Cheng, and L. Chen, “Investigating and optimizing the mix proportion of pumping wet-mix shotcrete with polypropylene fiber,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 150, pp. 14–23, Sep. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.169

-

X. Wu, H. Pan, K. Song, S. Xie, and Q. Zhao, “Influence of basalt fiber and flexural load on carbonation resistance of shotcrete: Experimental study and predictive model,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 478, p. 141421, Jun. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.141421

-

G. Zhang, L. Li, H. Shi, C. Chen, and K. Li, “The influence and mechanism of polyvinyl alcohol fiber on the mechanical properties and durability of high-performance shotcrete,” Buildings, Vol. 14, No. 10, p. 3200, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103200

-

P. Oreste, C. Oggeri, and G. Spagnoli, “Fiber-reinforced shotcrete lining for stabilizing rock blocks around underground cavities,” Transportation Geotechnics, Vol. 49, p. 101407, Nov. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2024.101407

-

H. Liao et al., “Effects of fiber and rubber materials on the dynamic mechanical behaviors and damage evolution of shotcrete under cyclic impact load,” Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 73, p. 106763, Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106763

-

X. Zhang, C. Ma, C. Liu, K. Zhang, J. Lu, and C. Liu, “Uniaxial tensile properties of steel fiber-reinforced recycled coarse aggregate shotcrete: Test and constitutive relationship,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 411, p. 134202, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134202

-

Z. Hu, Q. Wang, H. Lv, K. Li, J. Zhang, and Y. Ma, “Improved mechanical and macro-microscopic characteristics of shotcrete by incorporating hybrid alkali-resistant glass fibers,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 403, p. 133131, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133131

-

Q. Liu, P. Song, L. Li, Y. Wang, X. Wang, and J. Fang, “The effect of basalt fiber addition on cement concrete: A review focused on basalt fiber shotcrete,” Frontiers in Materials, Vol. 9, p. 10482, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2022.1048228

-

B. Ding, L. Zhang, and J. Liu, “The difference in weather resistance and corrosion process for different types of basalt fiber,” Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, Vol. 590, p. 121678, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2022.121678

-

K. Lou, P. Xiao, B. Wu, A. Kang, X. Wu, and Q. Shen, “Effects of fiber length and content on the performance of ultra-thin wearing course modified by basalt fibers,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 313, p. 125439, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125439

-

A. Liu, D. Kong, J. Jiang, L. Wang, C. Liu, and R. He, “Mechanical properties and microscopic mechanism of basalt fiber-reinforced red mud concrete,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 416, p. 135155, Feb. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135155

-

R. Pantawane and P. K. Sharma, “A critical review on basalt fibre geo-polymer concrete,” in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 2267, No. 1, p. 012014, May 2022, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2267/1/012014

-

D. Wong, G. Fabito, S. Debnath, M. Anwar, and I. J. Davies, “A critical review: Recent developments of natural fiber/rubber reinforced polymer composites,” Cleaner Materials, Vol. 13, p. 100261, Sep. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2024.100261

-

S. Qin and L. Wu, “Study on mechanical properties and mechanism of new basalt fiber reinforced concrete,” Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 22, p. e04290, Jul. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04290

-

M. T. Elshazli, K. Ramirez, A. Ibrahim, and M. Badran, “Mechanical, durability and corrosion properties of basalt fiber concrete,” Fibers, Vol. 10, No. 2, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/fib10020010

-

M. Li, F. Gong, and Z. Wu, “Study on mechanical properties of alkali-resistant basalt fiber reinforced concrete,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 245, p. 118424, Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118424

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.