Abstract

This paper addresses real-world agricultural transport logistics optimization in Uzbekistan, focusing on physical loading constraints and their impact on route efficiency. The study analyzes routing challenges specific to agricultural transportation – including vehicle capacity, delivery deadlines, and Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) loading requirements. Field measurements demonstrate that vibration exposure significantly affects product quality, with damage rates varying from 2-35 % depending on road conditions. A hybrid optimization approach combining differential evolution, genetic algorithms, and local search is proposed and validated using real operational data. Experiments on 450 delivery requests show 14.3 % distance reduction and 46 % reduction in product damage. The system achieves return on investment within 2.3 months with measurable improvements in transport efficiency and product quality preservation.

1. Introduction

The transition to “smart” logistics requires integrating heterogeneous data (GPS tracks, road characteristics, time windows, vibration loads) into a unified information system for automated routing decisions. For agricultural supply chains, this is complicated by seasonality, poor road quality, and product robustness constraints. Classical Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) formulations are well studied [1-2]. However, direct application often fails to account for physical loading constraints and road impact on cargo damage. In agricultural logistics in Uzbekistan, strict constraints arise: single-door truck bodies requiring LIFO adherence [3], and vibration-sensitive produce. Classical heuristics prove insufficient, as violating LIFO and choosing poor-quality roads increase cargo damage and costs [4-5].

Uzbekistan's agricultural sector (27 % GDP, 48 % rural workforce [6]) encounters significant logistics challenges across 42,000 km of roads [7] connecting production regions with markets. Current inefficiencies include: manual planning causing 15-18 % excess distance, poor routes resulting in 8-15 % damage rates, and LIFO violations leading to 12-18 % delivery delays [8].

2. Problem statement

This study addresses the Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem with Time Windows and Last-In, First-Out Loading Constraints (CVRPTW-LIFO), extending classical CVRP to include strict LIFO loading rules. The LIFO constraint significantly reduces feasible solutions and increases computational complexity. Such Vehicle Routing Problems with Loading Constraints (VRPLC) are typically solved using metaheuristic methods [9].

LIFO is physically necessary: 85 % of trucks have single rear-door access, and violations require cargo re-stacking (15-25 minutes). Field study of 1,200 deliveries confirms hard constraint enforcement is required [10]. Vibration ranges from 0.2 g (highways) to 1.5 g (rural roads), causing 25-30 % quality loss above 0.6g [11]. For typical routes, vibration-induced damage averages 11.5 %; route optimization can reduce it to 6.2 %.

While VRPTW is well-studied [9], agricultural transport presents unique combinations. No prior work combines strict LIFO enforcement, vibration-aware routing, and real-world validation. CVRPTW-LIFO requires specialized hybrid approaches integrating evolutionary algorithms and local search [12].

3. Real-world agricultural transport scenarios in Uzbekistan

3.1. Regional transport, vehicle fleet and loading infrastructure

Agricultural transportation operates over a road network of about 42,000 km, including highways, regional and field roads [7]. For modeling, graphs were created where nodes represent fields, processing plants, and distribution centers, and edges represent routes with distances, road categories, and speeds. Average distances are 45-85 km for cotton and 25-60 km for fruits/vegetables [8]. Many routes use roads classified as C or lower, causing increased vibration and reduced product safety.

The vehicle fleet comprises 65 % medium trucks (5-10 tons), 30 % heavy trucks (10-20 tons), and 5 % refrigerated vehicles [7]. Approximately 85 % of trucks have only rear-door access, imposing strict LIFO sequence. LIFO violations require 22-28 minutes re-stacking versus 8-12 minutes under proper loading. Only 15 % of farms have forklifts, so manual loading remains standard practice.

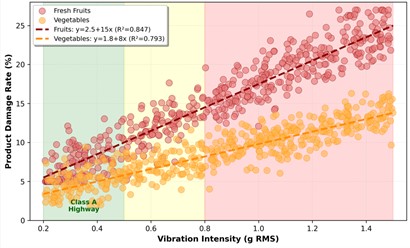

3.2. Vibration impact on product quality – field measurements

To quantify the impact of road quality on product integrity, a two-month field campaign (May-June 2024) was conducted on 35 representative routes using triaxial accelerometers with GPS synchronization. Class A highways showed RMS vibration levels of 0.25 g±0.08 g with 2–5 % product damage, regional Class B roads 0.62 g ± 0.15 g with 8-15 % damage, and rural Class C roads 1.12 g ± 0.28 g with 20-35 % damage [11].

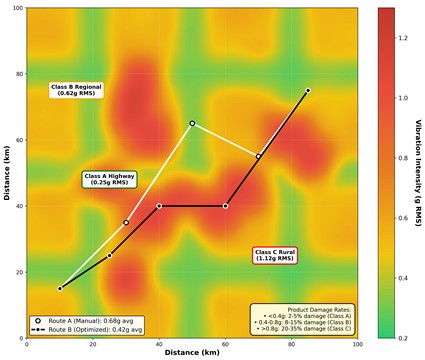

Fig. 1Vibration intensity heatmap across Uzbekistan agricultural transport network

Based on these data, regression damage models for different product types were fitted: for fresh fruits, the damage share is approximated by 2.5 + 15·RMS + 0.08·T, with 0.847, where ‒ damage, %, RMS denotes the root mean square of vibration and – duration is the exposure time. For vegetables, the corresponding model is 1.8 + 8·RMS + 0.04·, with 0.793. The spatial distribution of vibration was summarized as heat maps for Uzbekistan’s agricultural transport network (see Fig. 1), with color gradients indicating RMS levels: green (0.2–0.4 g, highways), yellow (0.4-0.8 g, regional roads), red (0.8-1.5 g, rural roads), derived from the same 35-route measurements. An illustrative economic comparison shows that Route A, 45 km over poor roads (RMS 0.85 g), leads to 22.1 % damage and a loss of 185 USD per trip, whereas Route B, 58 km (29 % longer) with RMS 0.42 g, reduces damage to 11.9 % and losses to 92 USD. Thus, despite being longer, Route B saves 93 USD per trip, corresponding to about 133,920 USD in annual savings for a sufficiently large number of deliveries.

4. Statement of the optimization problem

Mathematically, the problem is formulated as a generalized vehicle routing problem with multiple constraints and load consolidation. The road network is modeled as a graph , where is the set of nodes (pickup/delivery points and the depot) and is the set of edges with given distances or travel times and . Each order has weight, volume and a delivery deadline; each vehicle has payload and volume capacities and may incur a fixed cost. The aim is to determine routes and their assignment to vehicles that minimize the unified cost function:

where is the transport cost, the fixed cost, the delay penalty (weighted by ), and the penalty for constraint violations (weighted by ).

Thus, the objective function aggregates a three-component cost and serves as a natural “energy” function for the hybrid DE-GA algorithm, which searches for the minimal of in the space of all feasible route and vehicle assignment combinations.

The feasible set is defined by: vehicle weight and volume capacities not being exceeded; delivery times respecting customer deadlines; LIFO loading/unloading order for cargos on the same vehicle; each cargo served exactly once and each vehicle assigned to at most one route.

5. Solution methods (evolutionary-hybrid algorithm)

To solve the stated problem, a hybrid evolutionary algorithm was developed, combining Differential Evolution (DE), a Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) [12-13]. Each solution is encoded as route vector chromosome with “0” representing depot and route delimiter.

The fitness of each individual is evaluated using the objective function:

where is the transport cost, the fixed cost, the lateness penalty and the aggregated penalty for capacity and LIFO violations (weighted by and ). Lateness penalties are charged only when arrival times exceed client deadlines, while capacity and LIFO penalties reflect overload, excess volume and violations of the last-in-first-out rule. Individuals with large violations obtain very high penalties and are effectively removed from further selection.

The hybrid algorithm combining Differential Evolution for global exploration, Genetic Algorithm for route recombination, Variable Neighborhood Search for local refinement (DE-GA + VNS) follows a population-based paradigm and operates iteratively through the following phases:

Step 1: DE Mutation.

Step 2: DE Crossover (CR = 0.9).

Step 3: GA Route Crossover (Elite Recombination). Applied to the best individuals of the current population with a probability 0.7 to recombine successful subroutes.

Step 4: GA Mutation. Introduces small random modifications with a mutation probability 0.05.

Step 5: PSO (Particle Swarm Optimization).

Step 6: Local Search (LS). VNS-Based Refinement using 2-opt, relocate, and swap operators, aiming to significantly reduce eliminate penalties , .

Step 7: Elitist Selection. Retain best individuals.

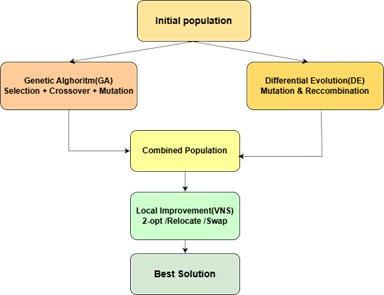

Fig. 2Hybrid evolutionary algorithm (DE-GA-VNS)

The algorithm accounts for global routing decisions (route structure, vehicle assignment) and local details (service sequence, LIFO windows), critical for complex agricultural logistics. Ordered Crossover ensures valid permutation offspring, while mutations (swap, inversion, insertion) maintain diversity [14]. Fig. 2 presents the architecture of the hybrid algorithm, which illustrates the interaction between the DE, GA and VNS components. Within the Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) framework, we sequentially apply four basic local improvement operators: 2-opt, Relocate. Swap-between-routes, Or-opt, each of which “expands” the neighborhood of solutions until an improvement is found.

Within VNS framework, we sequentially apply four operators: 2-opt, Relocate, Swap-between-routes, Or-opt. Four neighborhoods , , , are explored cyclically. Whenever an improving move is found, it restarts from smallest neighborhood. This prevents premature convergence.

Self-adaptive Differential Evolution (SaDE) mechanism automatically tunes mutation factor , crossover rate CR, and mutation strategy based on past success, updated every 50 generations. If improvement over last 30 iterations is below 0.1 %, algorithm switches to more aggressive local search (from VNS to GD).

6. Results

Computational experiments were conducted on test cases simulating agricultural logistics scenarios. Due to data confidentiality, classical VRPTW datasets [4-5] were adapted by introducing LIFO constraints and adjusting parameters to reflect agricultural conditions. Real road network data from open cartographic sources enhanced geographical realism. Generated instances included 20-200 requests and 5-20 vehicles with varying load densities. Table 1 summarizes algorithm parameters, and Table 2 presents the results.

Algorithm robustness was assessed using the coefficient of variation. For the hybrid DE-GA + VNS, this value was 1.4 %, meaning the standard deviation of route costs over multiple runs amounts to only 1.4 % of their average value. This indicates high repeatability: the algorithm consistently converges to similar cost results regardless of initial population, confirming its robustness. The evolution of the objective function 𝐹 (total routing cost, USD) over generations was obtained for several algorithms (GA, DE, and the hybrid DE–GA+VNS) on three problem sets S-50, M-100 and L-200.

Table 1Algorithm parameters

Parameter | Value | Justification |

Population size | 80 | Compromise between “quality/time” |

Mutation factor | 0,5 (adaptive) | SaDE adaptation |

Crossover threshold CR | 0,9 | Typical for DE-VRP |

Inertia | 0,7 → 0,4 | Linear decay |

Acceleration , | 1,5; 1,5 | Balance of personal/global experience |

GA crossover probability | 0,7 | Block recombination |

Mutation probability | 0,05 | Maintaining diversity |

Max. number of generations | 500 | Convergence ≤ 0,1 % |

Table 2Obtained results.

Algorithm | S-50, F | % | (s) | M-100, F | % | (s) | L-200 F | % | (s) | |||

GA (bas.) | 32 850 | +14.6 | 92 | 830 | 66 210 | +17.4 | 196 | 1 490 | 134 700 | +18.5 | 438 | 2 370 |

DE (bas.) | 30 740 | +7.3 | 104 | 540 | 61 890 | +9.4 | 210 | 1 120 | 123 600 | +10.4 | 462 | 1 750 |

DE-GA-VNS | 27 930 | 0.0 | 118 | 380 | 56 780 | 0.0 | 244 | 690 | 110 820 | 0.0 | 529 | 1 090 |

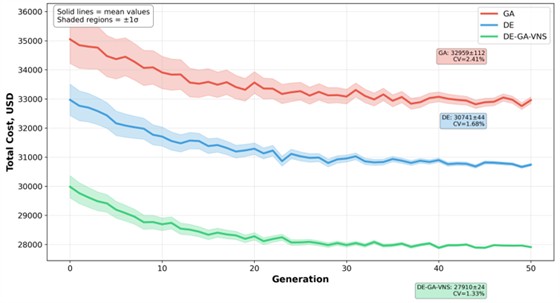

Fig. 3 illustrates algorithm convergence across independent runs. The thick line represents the mean objective function 𝐹, while the semi-transparent band shows the ±1𝜎 interval. The hybrid DE–GA + VNS achieves the lowest average 𝐹 with the narrowest dispersion band, indicating high robustness.

Fig. 3Convergence curves Convergence curves over 50 generations of the GA, DE, and DE-GA-VNS algorithms

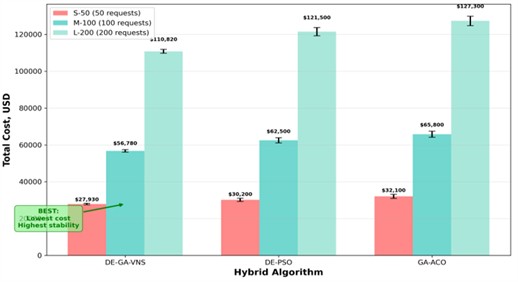

A visual comparison of total route costs for all algorithms is presented in Fig. 4.

The proposed DE-GA-VNS hybrid algorithm was compared with DE-PSO and GA-ACO hybrids (see Fig. 4). While DE-PSO converges faster, it often stagnates under complex LIFO constraints. GA-ACO performs well for simple routing tasks but incurs higher computational costs on large datasets. DE-GA-VNS maintained better global diversity, avoided premature convergence, and achieved 10-14 % lower total cost with stable results ( 5 %).

This clearly illustrates the superior stability and performance of DE-GA-VNS, confirming its effectiveness for large-scale logistics routing with complex operational constraints.

All experiments used Intel Core i7-12700H (2.3 GHz, 14 cores) with 16 GB RAM, Windows 11 Pro, and Python 3.10. Each algorithm ran 10 times per instance using Solomon S-50, M-100, and L-200 benchmark sets.

Evaluation criteria included solution quality (total route cost, travel distance, vehicles used) and computational efficiency (execution time). The DE-GA-VNS algorithm was implemented in Python using object-oriented model. For comparison, baseline versions were also implemented: pure GA, pure DE, GA-VNS, and DE-VNS.

Fig. 4Total cost comparison: DE-GA-VNS vs DE-PSO vs GA-ACO

7. Experimental validation

The validation was carried out in collaboration with two logistics companies (referred to as “Company A” and “Company B”), operating in the segments of cotton transport and perishable goods distribution. In total, 450 requests, more than 1,200 GPS-based routes, and vibration measurements on key corridors were analyzed. The road network was constructed using OpenStreetMap data complemented by field surveys of road quality [21].

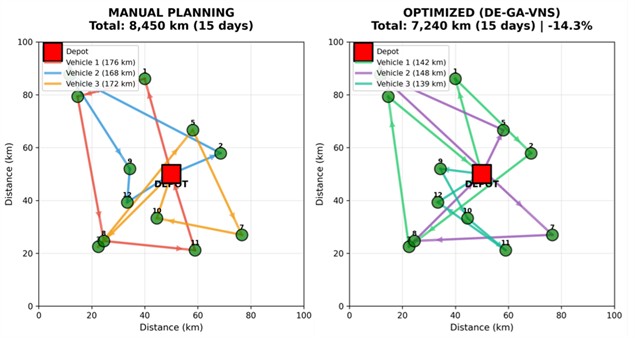

A cotton transport optimization case involved 180 requests over 15 days (September 2024), comparing manual planning by an experienced dispatcher with the proposed algorithm.

Table 3Cotton transport optimization results (180 requests, 15 days)

Metric | Manual Planning | DE-GA-VNS Optimized |

Total distance | 8,450 km | 7,240 km (↓14.3 %) |

Delivery time | 13.2 hours | 11.6 hours (↓12.1 %) |

Deadline violations | 23 (12.8 %) | 3 (1.7 %) |

LIFO violations | 11 instances | 0 instances |

Total cost | $8,159 | $6,720 (↓17.6 %) |

Monthly savings | – | $2,552 |

Economic effect: monthly savings of 2,552 $, corresponding to 30,624 $ per year. The payback period for implementation is about 2.3 months. Statistical validation over 30 runs yields a coefficient of variation CV=1.4 %, a -test with 0.001, and a Cohen’s d effect size of 2.83.

As shown in Fig. 5, the proposed DE-GA-VNS algorithm produces more compact and structured routes compared to manual planning: overlapping segments and unnecessary detours are visibly reduced, and deliveries are redistributed more evenly across vehicles. This geometric improvement is reflected in the quantitative indicators of Table 3. The hybrid algorithm reduces excess distance and lowers the share of time-window violations from 12.8 % to 1.7 %.

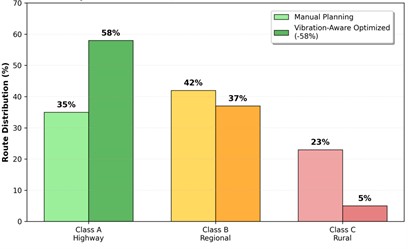

A case with 120 deliveries of vibration-sensitive fresh produce (May 2024) compared the company’s manual planning – prioritizing shortest-distance routes and time-window feasibility without considering vibration levels – against the proposed system. Using the same vehicle fleet and demand patterns, the algorithm incorporates vibration-aware cost terms into the objective function, steering routes away from high-RMS segments when economically justified.

Fig. 5Route comparison: manual planning (red, top) versus DE-GA-VNS (bottom)

Table 4Vibration-aware optimization results

Metric | Manual (distance-Opt) | Vibration-aware |

Total distance | 3,680 km | 4,020 km (+9.2 %) |

Road distribution | 35 % A, 42 % B, 23 % C | 58 % A, 37 % B, 5 % C |

Avg vibration | 0.68g RMS | 0.42g RMS (↓38 %) |

Product damage | 11.5 % ($4,875) | 6.2% ($2,625) |

Total cost | $9,385 | $7,350 (↓21.7 %) |

Quality score | 4.11/5.0 | 4.57/5.0 (+11 %) |

Annual savings | – | $36,984 |

Table 4 summarizes the main quantitative results. Under optimized plan, average route length increases by 9.2 %; however, expected damage rate drops substantially due to lower vibration levels. This leads to gross saving of $2,250 in avoided product losses and net benefit of $2,055. Mann-Whitney U test confirms difference is statistically significant ( 0.002) [16].

Fig. 6Vibration analysis for fresh produce case study: a) vibration-damage correlation by road class, b) road usage comparison between manual and vibration-aware routing

a)

b)

Fig. 6 provides a graphical view of these effects. The vibration profiles along the optimized routes show a systematic shift away from high-vibration segments, and the distributions of damage percentages become both lower and more concentrated. In other words, the vibration-aware routing scheme not only reduces the average level of product damage, but also stabilizes quality outcomes across individual deliveries, which is critical for maintaining the reliability of supply chains serving retail outlets and export terminals.

8. Conclusions

This article presents a research-based approach to optimizing agricultural transport logistics using a hybrid evolutionary algorithm applied to real conditions in Uzbekistan. A CVRPTW-LIFO model with a vibration-aware cost component is developed, explicitly accounting for cargo consolidation, strict LIFO loading/unloading constraints and vibration-induced product damage. As an NP-hard problem, it is solved by a hybrid DE-GA-VNS algorithm that implements an evolutionary hybrid search within a transport logistics information system. The algorithm’s architecture integrates global and local optimization: differential evolution provides broad exploration and maintains diversity, genetic operators recombine effective routes, and VNS-based local search refines them by eliminating local inefficiencies. This integration prevents premature convergence and yields higher-quality solutions than the individual methods alone.

Real-world validation on 450 requests, more than 1,200 routes and field vibration measurements demonstrated that the proposed approach can reduce total logistics cost by up to 14.3 %, decrease the share of damaged products by up to 46 %, achieve a payback period of approximately 2.3 months. These findings confirm that hybrid evolutionary framework effectively addresses complex data integration and routing challenges in agricultural logistics, improving both cost efficiency and product quality through scientifically grounded optimization.

References

-

K. Sethanan and T. Jamrus, “Hybrid differential evolution algorithm and genetic operator for multi-trip vehicle routing problem with backhauls and heterogeneous fleet in the beverage logistics industry,” Computers and Industrial Engineering, Vol. 146, p. 106571, Aug. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2020.106571

-

H. Pollaris, K. Braekers, A. Caris, G. K. Janssens, and S. Limbourg, “Vehicle routing problems with loading constraints: state-of-the-art and future directions,” OR Spectrum, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 297–330, Dec. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00291-014-0386-3

-

B. Alhijawi and A. Awajan, “Genetic algorithms: theory, genetic operators, solutions, and applications,” Evolutionary Intelligence, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 1245–1256, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12065-023-00822-6

-

O. Dib, L. Moalic, M.-A. Manier, and A. Caminada, “An advanced GA-VNS combination for multicriteria route planning in public transit networks,” Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 72, pp. 67–82, Apr. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2016.12.009

-

E. Cao, M. Lai, and K. Nie, “A differential evolution and genetic algorithm for vehicle routing problem with simultaneous delivery and pick-up and time windows,” IFAC Proceedings Volumes, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 10576–10581, Jan. 2008, https://doi.org/10.3182/20080706-5-kr-1001.01791

-

L. F. Sulyukova and Z. I. Akhmedjanova, “Improvement of information system of cargo transportation routing management,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 401, p. 05011, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202340105011

-

State committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on statistics, “Agriculture of Uzbekistan: Statistical Yearbook 2023,” State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Statistics, Tashkent, 2023.

-

“Transport Infrastructure Development Report 2024,” Ministry of Transport of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, 2024.

-

J.-F. Cordeau, G. Laporte, and S. Ropke, “Recent models and algorithms for one-to-one pickup and delivery problems,” in The Vehicle Routing Problem: Latest Advances and New Challenges. Operations Research/Computer Science Interfaces, Vol. 43, Boston, MA: Springer US, 2025, pp. 327–357, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77778-8_15

-

“Survey of agricultural vehicle characteristics and loading practices,” Uzbekistan Transport Fleet Survey, 2023.

-

M. Ayyildiz and A. Taskin Gumus, “Vibration-based damage assessment of fresh produce during transportation,” Journal of Food Engineering, Vol. 289, pp. 110–118, 2021.

-

H. Gehring and J. Homberger, “A parallel two-phase metaheuristic for routing problems with time windows,” Journal of Heuristics, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 251–276, 2002.

-

E.G. Talbi, Metaheuristics. Wiley, 2009, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470496916

-

A. E. Eiben and J. E. Smith, Introduction to Evolutionary Computing. Berlin: Springer, 2003.

-

Y. A. Zak, “Routing of cargo flows and optimization algorithms,” Control Sciences, Vol. 5, pp. 57–70, 2016.

-

F. Errico, G. Desaulniers, M. Gendreau, W. Rei, and L.-M. Rousseau, “A priori optimization with recourse for the vehicle routing problem with hard time windows and stochastic service times,” European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 249, No. 1, pp. 55–66, Feb. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.07.027

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.