Abstract

Hot and arid climates cause freshly laid concrete pavements to lose moisture rapidly, impeding cement hydration and preventing the concrete from achieving its design strength. Conventional curing methods (such as frequent water sprinkling or covering) are labor-intensive and resource-intensive. In this study, a new film-forming curing compound was developed using a local Uzbek petroleum wax byproduct (“Gach”) to mitigate moisture loss in fresh concrete. The effectiveness of this locally developed film-forming material was compared with that of imported curing compounds in terms of moisture retention and overall impact on concrete performance. Laboratory tests demonstrated that the Gach-based formulation can form an effective protective film at an application rate of about 300-350 g/m2, whereas the imported materials required around 400-600 g/m2 for adequate coverage. Using the Gach-based curing film reduced material consumption by approximately 12.5 % and lowered curing costs by over 50 % for a typical project, all while preserving the concrete’s strength and durability. These results highlight the potential of using local materials like Gach to improve concrete curing efficiency and performance in hot, dry climatic conditions.

1. Introduction

Fresh cement concrete pavements in hot, dry climate regions experience accelerated moisture evaporation. This rapid drying of the concrete surface slows or halts cement hydration and can prevent the pavement from reaching its designed strength within the expected time frame. As a result, the physical and mechanical properties of the concrete (such as compressive strength, frost resistance, and corrosion resistance) deteriorate, especially in the upper layer of the pavement where moisture loss is most pronounced. Researchers worldwide have explored various curing compounds (film-forming materials) to address moisture loss in concrete. For example, Bin Xue et al. (2016) found that acrylic-based and composite film-forming materials were most effective at retaining moisture and preventing surface microcracks, whereas paraffin- and sodium silicate-based materials were somewhat less effective [1]. Maoqing Li et al. (2024) demonstrated that using a composite curing agent containing paraffin emulsion and polymers improved concrete’s compressive and flexural strength and reduced drying shrinkage [2]. Similarly, Goel and Kumar (2022) showed that wax- and resin-based curing compounds form a strong, elastic film on the concrete surface, significantly reducing the number of microcracks compared to traditional water curing [3]. In Ethiopia, Ayalew and colleagues (2021) developed a liquid membrane-forming curing compound that improved the compressive strength of concrete, although it was less effective in reducing water absorption; conventional water curing still performed better in limiting absorption in that study. Other studies have evaluated curing compounds under extreme conditions [4]. Whiting and Snyder (2003) reported that in hot, windy conditions, concrete curing compounds can effectively retain surface moisture if applied in two coats or in a sufficiently thick layer, thereby protecting the concrete from microcracking and preserving its structural integrity [5]. Chyliński et al. (2022) observed that paraffin-based curing agents provided the highest moisture retention and increased the surface density of concrete, while polymer-dispersion agents had positive but lesser effects [6]. Yuan et al. (2019) demonstrated that an emulsion wax curing agent (EWCA) forms a stable membrane on the concrete surface, reducing water penetration and evaporation across various weather conditions and thus minimizing crack formation [7]. These prior works underscore the importance of film-forming curing materials for maintaining concrete moisture and strength, and they highlight that compositions based on waxes, polymers, or composites can offer improvements over basic curing methods.

In Uzbekistan, numerous studies by E. Kholmukhammedov, T. Amirov, and others have investigated cement concrete mix design, processing technology, and standard curing methods to improve road pavement quality. However, very little research has focused on film-forming curing materials for concrete pavements under local climate conditions. This gap in the literature is significant given Uzbekistan’s hot and dry climate. The present study aims to address this gap by developing a new film-forming curing compound using locally available materials (including “Gach”, a petroleum wax residue) and evaluating its effectiveness in comparison with imported curing compounds. The novelty of this work lies in leveraging a local industrial byproduct for concrete curing and demonstrating its benefits in terms of moisture retention and cost-effectiveness under harsh climatic conditions [8].

2. Materials and methods

Film-forming materials must allow the use of modern machine mechanisms for applying them to the surface of freshly laid road concrete and ensure the possibility of mechanized application of film-forming materials without stopping spraying and washing for at least one shift. The recommended value of the conditional (technical) viscosity of the aqueous solution of the film-forming material, measured using a VZ-4 type technical viscometer, should not exceed 25 sec (at an air temperature of (18+/–2) °C) and should be at least 15 sec. The aqueous solution of film-forming materials should not contain large particles (size greater than 1.0 mm) and foreign impurities. If the nominal viscosity of the aqueous solutions of the film-forming material exceeds 25 sec or is less than 15 sec, the probability that the sprayers of modern machines and mechanisms will not be able to mechanically distribute the material over the surface of the coating increases. With minimal coating slopes, the probability of film-forming material leaking from the surface increases. The recommended pH value (medium acidity) for aqueous film-forming materials should be pH = 7.0-9.0, and the density of film-forming materials should be 0.9-1.1 g/cm3. The consumption rate of film-forming materials is set at more than 100 g/m2 [9, 10].

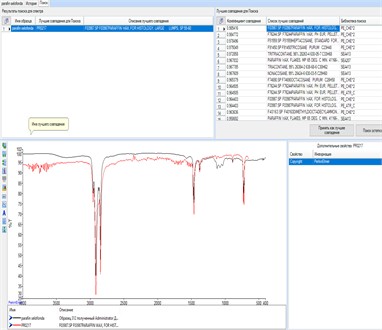

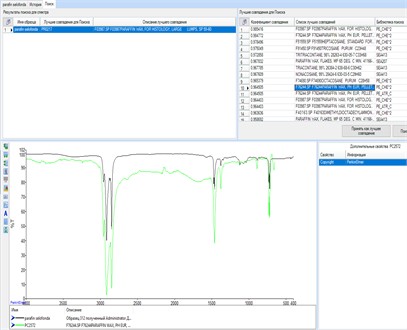

The composition of the BASF company's Masterkure 217 film-forming materials used in the care of freshly laid cement-concrete road surfaces was studied, and their chemical composition was tested using an IR spectrometer laboratory setup.

Composition Development: To address the problem, we first analyzed a commercially available curing compound as a benchmark. The composition of BASF’s MasterKure 217 film-forming curing compound (imported to Uzbekistan) was examined using infrared (IR) spectroscopy (Fig. 1). This analysis provided insight into the chemical components (such as waxes, oils, and additives) used in effective curing agents. Guided by these findings and considering locally available resources, we developed three candidate film-forming compositions using domestic raw materials in the Republic of Uzbekistan (Table 1-3).

Fig. 1Composition of the film-forming material Masterkure 217 by BASF, determined using a laboratory IR spectrometer setup

Table 1Composition I (paraffin-based)

Component / cost type | Quantity (g) | Unit price (uzs/kg or lt) | Total price (uzs) |

Paraffin | 875 | 50000 | 43750 |

Sodium fluoride | 52.5 | 300000 | 15750 |

DAE | 38.5 | 25000 | 962 |

Oleic acid | 17.5 | 50000 | 875 |

Technical oil | 105 | 20000 | 2100 |

Latex | 182 | 30000 | 5460 |

Costs for water, energy, labor, and other expenses | – | – | 10000 |

Total expenses | – | – | 79897 |

Table 2Composition II (based on GACH)

Component / Cost Type | Quantity (g) | Unit price (uzs/kg or lt) | Total price (uzs) |

GACH | 875 | 20000 | 17500 |

Sodium fluoride | 52.5 | 300000 | 15750 |

DAE | 38.5 | 25000 | 962 |

Oleic acid | 17.5 | 50000 | 875 |

Costs for water, energy, labor, and other expenses | – | – | 10000 |

Total expenses | – | – | 44087 |

Table 3Composition III (paraffin-based)

Component / cost type | Quantity (g) | Unit price (uzs/kg or lt) | Total price (uzs) |

Paraffin | 875 | 50000 | 43750 |

Sodium fluoride | 52.5 | 300000 | 15750 |

DAE | 38.5 | 25000 | 962 |

Oleic acid | 17.5 | 50000 | 875 |

Costs for water, energy, labor, and other expenses | – | – | 10000 |

Total expenses | – | – | 71337 |

All three compositions were prepared in the laboratory by heating and mixing the ingredients until a homogeneous emulsion was formed. Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3 summarize the components and approximate costs for manufacturing 1 kg of each composition. Based on the cost analysis, Composition II (using Gach) is the most economical: for instance, producing 1 kg of the Gach-based material costs about 44100 uzs, roughly half the cost of Composition I (≈ 79900 uzs) and significantly less than Composition III (≈ 71300 uzs). This translates to a ~45 % cost reduction in material production for Composition II compared to the paraffin+latex formulation. The substantially lower cost is due to the inexpensive Gach residue replacing the costly refined paraffin and latex components. These cost considerations, combined with the health compliance issue of Composition I, suggest that the Gach-based Composition II could be a very attractive option if its performance proves adequate (Table 4).

Table 4Economic efficiency of paving

Indicator | New material | Existing material | Savings / difference |

Square | 18 500 m² | 18 500 m² | – |

Consumption rate (per 1 m2) | 350 g = 0.35 liters | 400 g = 0.40 liters | 0.05 L savings ≈ 12.5 % |

Total expenditure | 6,475,000 g = 6,475 liters | 7,400,000 g = 7,400 liters | 925 L savings ≈ 12.5 % |

Price / 1000 g | 11 021,75 sum | 20 000 sum | – |

Price /g | ≈ 11,02175 sum/g | 20 sum/g | – |

Total costs | ~ 71 379 126 uzs | 148 000 000 uzs | ~ 76,620,874 uzs, savings ≈ 51.8 % |

Using the new material to pave a 1 km long and 18.5 m wide cement-concrete road surface with a film saves about 51.8 % of costs.

This also prevents hydrophobicity of the cement-concrete pavement, reduces material consumption by approximately 12.5 %, which ensures convenience in terms of resources, transportation, storage, and application.

Composition I contain latex, while composition II is based on “Gach”. Gach is a paraffin residue obtained during oil refining, also known as wax oil mixture or petroleum wax. The main components of this product are hydrocarbons, primarily paraffins and naphthalenes, which have properties similar to fatty substances. The solid and viscous structure of gach allows it to be used in construction, the oil industry, and other fields.

The advantage of composition II is that during the reaction process, it is not necessary to add any oil instead of the oil used to dissolve the paraffin, as the incompletely processed oil in the gach composition allows it to be used directly for dissolving the gach.

The composition with the addition of latex is not economically suitable for us due to the high cost of latex substance. The use of film-forming material should not harm workers' health, and the use of Latex BS-50 chemical material does not meet the requirements of GOST 12.1.007-76 [10].

Testing Procedure: The performance of the developed compositions was evaluated through a series of laboratory and field-mimicking tests. First, the optimal application rate for each film-forming material was determined following the procedure outlined in ODM 218.3.039-2014 “Recommendations for testing film-forming materials for curing newly placed concrete” [11]. Freshly mixed concrete slabs (meeting GOST 26633-2012 requirements for heavy concrete [13]) were prepared, and each curing composition was sprayed onto the concrete surface. Application was done in two layers to ensure complete coverage, using a mechanized sprayer with the nozzle boom set ~50-60 cm above the surface. For moderate ambient temperatures (up to 25 °C), a total of at least 400 g/m2 (in two coats of ~200 g/m2 each) was applied, and for hotter conditions (>25 °C), about 600 g/m2 total (~300 g/m2 per coat) was applied. After spraying the first coat, we waited ~25-30 minutes for it to form a film and begin to dry, then applied the second coat. Care was taken to leave no area untreated, including the edges of the slabs. The sprayer speed and nozzle flow were adjusted to deliver the target application rate uniformly. Fig. 2 shows an example of the film-forming material being applied to a freshly laid concrete surface using the spraying equipment. After application, the water retention performance of each curing treatment was evaluated by monitoring the moisture loss from the concrete. Specifically, the specific water loss (kg of water evaporated per m2 from the concrete over 72 hours) was measured in a controlled hot/dry environment for concrete specimens with and without the curing film. These tests followed the guidelines of ODM 218.3.039-2014 [11] and the Uzbekistan Republic Construction Regulation 06.03-23 “Automobile Roads” [12], which provide standard methods for assessing curing compound effectiveness. By comparing the weight of concrete samples before and after the curing period, we quantified how much water evaporated from each sample. A lower water loss indicates a better curing effectiveness (higher water retention). In addition, visual inspections were made for the presence of surface microcracks or any signs of insufficient curing.

Fig. 2Application of film-forming materials to the surface of freshly laid cement concrete. Photograph taken by Tukhtayev Matchon Bekjonovich in the laboratory and on field test sections of newly constructed cement concrete pavement, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

We also conducted qualitative chemical tests on the cured concrete surfaces to verify film coverage and integrity (as illustrated in Fig. 3). In one test, a 10 % hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution was sprayed on the concrete surface: if the curing film fully covered the concrete, the acid would not readily penetrate to react with the cement hydration products (thus minimal effervescence or surface etching would be observed). In another test, a 1 % phenolphthalein solution was applied: phenolphthalein turns pink in contact with the alkaline concrete pore solution, so a well-sealed surface would show little to no coloration (indicating the film prevented the indicator from reaching the concrete). These tests helped confirm whether the film-forming compound created a continuous protective layer over the concrete.

Fig. 3Testing film-forming materials: a) testing the film-forming material with a 10 % solution of hydrochloric acid; b) testing the film-forming material with a 1 % solution of phenolphthalein. Photograph taken by Tukhtayev Matchon Bekjonovich in the laboratory and on field test sections of newly constructed cement concrete pavement, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

a)

b)

Based on the data presented above, summarizing the results of the test methods, we can see that when technically and economically comparing the three compositions we manufactured, the Gach-based composition has an advantage. In general, if we bring the consumption rate to the standard, then for the formation of a film per 1 m2 of surface, a consumption rate of 300-350 g/m2 corresponds. In the remaining compositions, mainly, a consumption rate of 400-600 g/m2 was given for film formation per 1 m2 of surface. From this, it can be seen that among the recommended compositions of film-forming materials, the material consumption of the composition prepared with “Gach” is economical, as well as the low consumption rate when applying to freshly laid cement-concrete pavement for film formation is one of our achievements.

For the full functioning of film-forming materials used for the care of freshly laid cement-concrete pavements on highways and airfields, it is necessary to pay attention to the storage conditions and shelf life of film-forming materials. After application to the surface of the cement-concrete coating, the material forms droplets on the surface of the coating and does not spread, particles larger than 1 mm are formed, and separation occurs.

Finally, the storage stability and shelf-life of the film-forming materials were examined. We subjected an aged sample of the Gach-based composition (beyond its recommended shelf life) to the same application test to observe its behavior (Fig. 4). We found that an expired or improperly stored film-forming emulsion can undergo irreversible separation: upon spraying, the old material formed droplets and clumps on the concrete instead of a uniform film, and particles larger than 1 mm were observed (due to coagulation of components). Such degraded material failed to cover the surface and even hardened inside the spray nozzle, causing equipment clogging. These observations underscore the importance of proper storage and adhering to the shelf-life of curing compounds. In practical implementation, users should follow standard guidelines for storing petroleum-based construction materials (e.g., GOST 1510-2022 [14] on packaging, labeling, and storage of oil products) to preserve the quality of film-forming curing agents.

Fig. 4Verification of film-forming materials: a) type of film-forming material with expired shelf life, sprayed on the surface of freshly laid cement concrete; b) separation of film-forming material and formation of particles larger than 1 mm. Photograph taken by Tukhtayev Matchon Bekjonovich in the laboratory and on field test sections of newly constructed cement concrete pavement, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

a)

b)

3. Results and discussion

Composition II (Gach-based) exhibited a significant technical and economic advantage over the other formulations. We found that an application of roughly 300-350 g/m2 of the Gach-based material was sufficient to form a continuous, moisture-retaining film on the concrete surface. In contrast, Composition I (paraffin + latex) and Composition III (paraffin-only) generally required about 400-600 g/m² to achieve a comparable level of film coverage and curing performance. In other words, the Gach-based compound met the necessary curing criteria with about 20-30 % less material. This lower required dosage indicates that Composition II has a higher water-retention efficiency – it can reduce evaporation with a thinner application, likely due to Gach’s favorable film-forming and moisture-sealing properties.

Correspondingly, the specific water loss measurements reflected better performance for the Gach-based film. At the standard application rate (~350 g/m2), Composition II kept the water loss well below the allowable threshold defined in the test recommendations, whereas the paraffin-based compositions needed a heavier coat (~500 g/m2 or more) to reach the same level of moisture preservation. Although exact evaporation figures vary with conditions, this trend confirms that the water-holding capacity of the Gach-based material is superior to that of the alternatives.

Composition I (with latex) formed a slightly more elastic film, but as noted earlier, its advantages are offset by cost and safety issues. In fact, given that the latex-based formula fails to meet safety standard GOST 12.1.007-76 [10], it would likely be disqualified from practical use despite its curing efficacy. Composition III (paraffin only) performed reasonably well but did not retain moisture quite as effectively as the Gach-based Composition II, and it remained relatively costly. Meanwhile, Composition II demonstrated no drawbacks in application or performance: it sprayed on uniformly, did not exhibit any running or sagging even on sloped sections, and dried to a robust film. The success of the Gach formulation is a notable achievement of this research, showing that a local industrial byproduct can replace imported chemicals without loss of quality in concrete curing.

Another crucial finding concerns the storage and handling of these curing compounds. As described in the Methods, using material past its expiration or improperly stored material leads to failure in film formation. During our trials, an expired batch of the Gach-based emulsion showed complete breakdown: it could not form a cohesive film and instead clogged the spraying nozzle with clumps. This result serves as a reminder that even the best formulation will perform poorly if its quality is compromised. Therefore, strict adherence to storage guidelines and shelf-life is necessary when implementing these materials in the field. Ensuring fresh, well-mixed material will prevent issues such as nozzle blockage and uneven coverage. Fortunately, all tests with properly stored (within shelf-life) material were successful, indicating that under correct usage conditions, the new film-forming compounds are reliable for curing concrete.

4. Practical implementation

Implementation in road projects: The outcomes of this research can be readily applied in real road construction and maintenance projects, especially in regions with hot and arid climates. Using the new Gach-based film-forming curing material in field conditions is expected to significantly improve curing efficiency and reduce costs. For example, we estimated that for a standard highway project (approximately 1 km of cement concrete pavement, 18.5 m wide), adopting the new curing compound in place of conventional methods could reduce curing-related costs by roughly 51.8 %. This substantial cost savings comes from the lower material price of the Gach-based compound and the reduced application rate needed to achieve effective curing. In practical terms, road construction agencies can save tens of millions of uzs on each kilometer of concrete pavement by switching to the locally produced film-forming material. At the same time, the improved moisture retention provided by this curing film will enhance the quality of the pavement – minimizing early-age cracking and ensuring that the concrete reaches its intended strength and durability.

Adoption and recommendations: To implement these findings, it is recommended that construction specifications and guidelines be updated to include the option of using Gach-based film-forming curing compounds. Contractors and engineers should be made aware of the proper usage of the material: it should be applied according to the tested optimal rate (around 0.3-0.35 kg/m2 in two coats) for best results. Additionally, quality control measures should be in place – for instance, verifying the shelf-life and consistency of the emulsion before use, as only fresh and well-stirred material will perform reliably (per our findings on storage-related issues). Ensuring compliance with relevant standards (such as GOST 1510-2022 [14] for storage and handling of petroleum products and the ODM guidelines [11] for testing curing materials) will help maintain the material’s effectiveness from the plant to the construction site. Pilot projects could be initiated on real highway sections to further demonstrate the performance of the Gach-based curing compound under on-site conditions and to refine application procedures if necessary.

5. Conclusions

In dry and hot climates, proper curing of concrete pavement is vital to prevent rapid dehydration and strength loss. This study showed that film-forming curing materials can effectively mitigate moisture evaporation from freshly laid cement concrete pavements, thereby ensuring sufficient hydration and strength development. We developed new film-forming curing compositions using local Uzbek materials and compared them with an imported benchmark. The results confirmed that a locally produced Gach-based curing compound outperforms the imported analogue in both technical efficacy and cost-efficiency. The Gach-based material formed a waterproof membrane that retained moisture better (achieving the required curing effect with a lower application rate) and was significantly more economical in terms of material cost and consumption. Domestic film-forming materials of the types tested are thus more advantageous than imported curing compounds under Uzbekistan’s climate conditions, offering equal or better water retention and strength preservation at lower cost. Overall, this research highlights the importance of using film-forming curing compounds for newly laid concrete pavements in harsh climates and demonstrates the feasibility of leveraging local industrial byproducts (like Gach wax) to improve concrete curing practices. The findings can be directly applied to improve the quality and durability of concrete road surfaces in construction. By adopting the recommended Gach-based curing material, construction projects in the region can achieve better concrete performance while reducing curing costs and reliance on imported products.

References

-

B. Xue, J. Pei, Y. Sheng, and R. Li, “Effect of curing compounds on the properties and microstructure of cement concretes,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 101, pp. 410–416, Dec. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.124

-

C. Wei et al., “Preparation and performance of cement-stabilized base external curing agent in a desert environment,” Buildings, Vol. 14, No. 5, p. 1465, May 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14051465

-

P. Goel and R. Kumar, “A comparative investigation on the effectiveness of a wax and a resin based curing compound as an alternate of water curing for concrete pavement slab,” in Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 575–583, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87379-0_43

-

R. Ayalew, K. Admassu, and S. Dagnaw, “Investigating the effectiveness of liquid membrane – forming concrete curing compounds produced in Ethiopia,” in Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering, Vol. 2, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021, pp. 453–466, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80618-7_31

-

N. M. Whiting and M. B. Snyder, “Effectiveness of Portland cement concrete curing compounds,” Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, Vol. 1834, No. 1, pp. 59–68, Jan. 2003, https://doi.org/10.3141/1834-08

-

F. Chyliński, A. Michalik, and M. Kozicki, “Effectiveness of curing compounds for concrete,” Materials, Vol. 15, No. 7, p. 2699, Apr. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15072699

-

J.-B. Yuan, J.-L. Yao, H.-C. Wang, and M.-J. Qu, “Membrane-forming performance and application of emulsion wax curing agent (EWCA) for cement concrete curing,” in Sustainable Civil Infrastructures, pp. 274–286, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61633-9_18

-

M. B. To’Xtaev, “Improving Methods for Maintaining Newly Laid Cement Concrete Pavements on Highways,” (in Uzbek/Russian), Tashkent, 2020.

-

“Petroleum paraffin (solid): technical specifications,” GOST 23683-2021, 2021.

-

“Occupational safety standards system – Hazardous substances. Classification and general safety requirements,” GOST 12.1.007-76, 1976.

-

“Recommendations for testing film-forming materials for curing newly placed concrete,” Russia, ODM 218.3.039-2014, 2014.

-

“Automobile Roads,” Uzbekistan Republic, Construction Regulation (QR) 06.03-23, 2023.

-

“Heavy and fine-grained concretes – technical specifications,” GOST 26633-2012, 2012.

-

“Oil and petroleum products – Marking, packaging, transportation, and storage,” GOST 1510-2022, 2022.

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.