Abstract

The article presents the results of vibration monitoring, the purpose of which was to determine the vibration parameters of an existing industrial building from pile driving. Ground vibrations induced by pile driving are transmitted through the subsurface via elastic wave propagation mechanisms and may remain perceptible at significant offsets, frequently exceeding a few hundred meters from the source. The main evaluation parameters of vibration: vibration displacement (amplitude), vibration speed, frequency and vibration acceleration. Vibration parameters were measured at different distances from the excitation source: near the pile, at a distance of 10, 50, 100 m. According to the results of the measurements, the dependence of the vibration parameter changes on the time of hammering based on the analysis of which the dependence of the vibration parameter changes depending on the distance from the excitation source was determined. The work also presents statistical data of the obtained results, on the basis of which an analysis of the relationship of the received individual values of the vibration indicators was carried out.

1. Introduction

Modern construction places high standards and demands on engineers for the construction and design process. In response to these challenges, established traditional approaches are gradually giving way to new, more cost-effective and environmentally efficient technologies that promote energy conservation and reduce environmental impact. The issue of updating technological and technical solutions also affected foundation construction, in particular the technology of constructing deep foundations (pile foundations) [2]. Pile foundations play a fundamental role in the construction industry, ensuring the stability and durability of buildings and structures [1].

Pile foundations are currently the focus of attention at construction sites in Kazakhstan and are in demand as one of the most preferred foundation types. This is due not only to the need for load-bearing capacity for the construction of buildings and structures, including high-rise structures, but also to a number of other factors that make pile foundations indispensable in modern construction practice in Kazakhstan. This has led to the emergence of new technologies and equipment for pile foundation installation, which offer direct advantages over established technologies in the construction market.

Vibration monitoring tests of dynamic impacts during pile driving on the structure were conducted (pouring): during concrete work, structures are in the process of achieving 70 % strength; after this strength has been achieved, they are most sensitive to dynamic impacts. According to standard, freshly placed concrete must not be subjected to vibration loads until it has reached sufficient strength. However, under construction conditions, completely stopping pile driving for the entire period of concrete curing is not feasible. Therefore, pile driving is permitted in remote areas where the vibration level recorded by vibration monitoring equipment does not exceed the maximum permissible vibration velocity (mm/s) for immature structures. This approach minimizes the impact of vibration on freshly placed concrete while ensuring the continuation of construction work [3].

To assess the impact of construction vibrations, their nature is first determined – whether they are short-term (pulsed) or long-term (continuous/regular). Pile driving within a project involves a series of short-term dynamic impacts (individual impacts/pile driving). When driving large numbers of piles simultaneously using multiple machines, vibrations have a prolonged effect. Due to the repeated nature of the operations, cumulative effects (soil compaction, fatigue damage to elements, long-term deformations) are possible. Therefore, the impact should be considered a regular, short-term event with an increased risk of long-term consequences.

2. Literature review

The object of monitoring was a building located on an industrial site in Pavlodar. The Pulp Conditioning Area served as a testing ground for driving piles for vibration monitoring purposes.

Pile driving is recognized as one of the loudest activities in construction. While the resulting noise can annoy people located far from the site, it almost never causes actual structural damage [1]. However, because of the high noise and vibration levels, nearby residents may mistakenly believe their buildings have been damaged and start looking for signs of harm. Like explosive blasts and sonic booms, pile driving generates ground vibrations. Unlike blasting, though, the vibrations from pile driving are limited by the mechanical energy of the system. In other words, a hammer weighing W and falling from a height cannot deliver more energy than on impact. Each hammer strike produces both noise and ground vibration.

The elastic deformation of the soil generates elastic waves [2]. In a uniform, isotropic, and linearly elastic medium, two main types of waves can travel through the ground: body waves and surface waves [3]. Body waves include compression (P) waves and shear (S) waves, while the main surface wave of interest is the Rayleigh (R) wave.

In saturated soils, P waves move only through the pore fluid, since the fluid is nearly incompressible. Because fluids cannot resist shear, the velocity of S waves depends on the stiffness of the soil’s solid skeleton [3]. When body waves reach the surface of a homogeneous, isotropic, elastic half-space, they generate Rayleigh waves.

In an idealized model, the pile tip acts as the source of these waves. As the pile is driven, body waves radiate outward in spherical patterns and reach the ground surface, where they reflect and refract, producing Rayleigh waves that travel along the surface in cylindrical patterns [3]. As the waves spread out, they cover a larger volume of soil, which reduces their energy density through geometric damping. Because body waves spread spherically, their intensity decreases more quickly than that of surface waves [3-7].

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Engineering and geological conditions of the construction site

Based on the field description of soils and the results of laboratory tests, the soils comprising the survey site were divided into engineering-geological elements in the strati-graphic sequence of their occurrence according to the requirements of the standard [8]: EGE-1. Loam – aQII-III; EGE-2. Silty sand – aQII-III; EGE-3. Loam – N1-2pv; EGE-4. Medium-grained sand – N1-2pv; EGE-5. Clay – N1-2pv; EGE-6. Fine sand – N1-2pv; EGE-7. Clay – N1-2pv.

For each selected engineering-geological element, specific values of physical and mechanical properties, data from shear and compression tests using laboratory methods, and calculations of standard and design characteristics of soils are provided.

Table 1Engineering-geological element 1

No. | Name of indicators | Unit of measurement | Average value (EGE1) |

1 | Natural moisture content | % | 4.7 |

2 | Moisture content at the liquid limit | % | 17 |

3 | Moisture content at the rolling limit | % | 12 |

4 | Plasticity index | % | 4.8 |

5 | Consistency | – | –1.7 |

6 | Soil density | gr/cm3 | 1.76 |

7 | Soil particle density | gr/cm3 | 2.7 |

8 | Porosity coefficient | 0.610 | |

9 | Moisture content | 0.209 | |

10 | Specific adhesion (at natural moisture content) | MPa | 0.008 |

11 | Angle of internal friction (at natural moisture content) | degree | 13.1 |

12 | Compression modulus of deformation in the range of 0.1-0.6 MPa (at Sr) | MPa | 22.6 |

13 | Modulus of deformation by triaxial compression, MPa | MPa | 16.8 |

14 | Poisson's ratio | – | 0.321 |

EGE–2. Dust sand aQII-III – characterised by a determining fraction (particles smaller than 0.1 mm) with an average value of 26.6 %, in a water-saturated state.

There is no frozen soil in Kazakhstan, but there is soil that freezes and thaws seasonally. For the city of Pavlodar, soil freezing ranges from 1.76 to a maximum of 2.30 m and depends on the type of soil. It is not the soil that freezes, but the water in the soil mass, and the groundwater at the survey site has been exposed by boreholes and has settled at a depth of 2.8-5.6 m. As the results of engineering and geological surveys show, there is no need to take into account the frozen state of the soil base.

3.2. Technical characteristics of pile foundations

Driving shall be performed using a hydraulic hammer with an impact weight of at least 7 t. Driving concrete piles series C1of 12.0 m long, cross section 30×30 cm performed at a distance of 15 m. from the site of vibration monitoring of dynamic impacts on the industrial building. (with driving into the ground to a depth of 11.0 m). C-2 piles with a length of 12.0 m and a depth of 11.0 m in the leading borehole can be driven into the ground to a depth of 1.0 m at a distance of 5.0 m.

3.3. Vibration monitoring of pile driving with leader drilling

Two vibration monitoring tests were conducted during pile driving using leader drilling technology. Test conditions:

− Number of tests – 2.

− Distance between vibration sensors and pile driving site – 2.5 m (200 mm) and 5 m (200 mm), with the diameter of the drilling rig auger indicated in brackets.

− Vibration parameters will be monitored in accordance with the requirements [10].

Test objectives:

– To record vibration levels during pile driving with leader drilling.

– A comparative analysis of vibration intensity at various distances from the source was carried out.

– Initial data was compiled to assess the dynamic impact on structures and soil.

The test results are presented in section 3, with the measurement results presented in tables and graphs showing the “speed-time” and “speed-frequency” relationships for each of the two observation points.

3.4. Testing of pile driving without pilot drilling

Pile driving was performed using an HHK-7A hydraulic hammer based on a JUNTTAN PM25 pile driving rig at the autoclave oxidation site of industrial construction site. The depth of the piles driven was 8.0-9.0 m. Weather conditions during the test were good, ranging from +5 ℃ to +20 ℃. The test results were taken from three average values for each distance and demonstrate a clear dependence of the vibration level on the distance from the source. The attenuation of the maximum vibration velocity ( axis) with increasing distance. Beyond 90 m the attenuation is equal to the background vibration, so there is no point in continuing vibration monitoring for complete attenuation. Monitoring is conducted 2-6 hours before pile driving to record background vibrations caused by construction equipment and traffic. This allows for the determination of a baseline vibration level, against which the vibration impact during pile driving is subsequently recorded. Mukhanov D. carried out vibration monitoring measurements of driving pile foundations at the construction site on September 19, 2025 Fig. 1.

Fig. 1Vibration monitoring at a construction site

Vibration monitoring was performed using a Profound VIBRA+ device, using a 3D seismic sensor. The vibration measurement interval was 5 s. Tests were performed in accordance with the requirements of DIN 4150-3, which specifies a maximum permissible vibration level (acceleration rate) of 5.00 mm/s (from 0-10 Hz). Sensor Installation Location for Testing. During vibration monitoring, the sensor was installed on the very edge of the hangar building’s foundation slab, or on the closest grillage to the vibration point and was installed according to the work program [9-12].

4. Results analysis

4.1. Checking the background effects on the industrial building

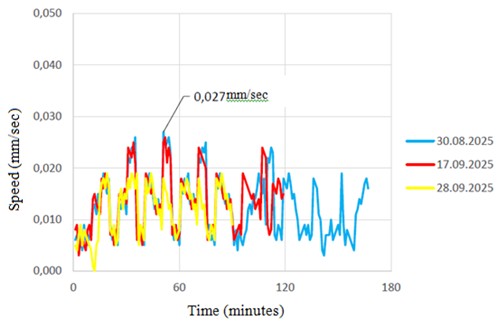

In accordance with the program, the level of background vibrations was recorded before the start of shock operations. There were 3 tests of vibration monitoring of background vibrations with dates: August 30, 2025, September 17 and 28, 2025, all three tests are shown in one table.

On August 30, vibration monitoring was conducted 2.5 hours before the start of pile driving, on September 17, 2 hours before pile driving, and on September 28, 1.5 hours before pile driving. The measurement results are presented.

An analysis of the recordings showed that the level of background vibrations does not exceed 0.27 mm/s on any of the three axes from the three tests, which corresponds to the category Safe/Non-critical according to the program. The frequency indicators gave a jump to 8.5 Hz at times, which is also uncritical. Spectral analysis did not reveal pronounced resonant peaks that coincide with the calculated natural frequencies of the building structures.

Table 2Background vibration readings

Date of measurement | Measurement duration | Max. speed | Security clearance level |

30.08.2025 | 2.5 hours | 0.27 mm/s | Safe |

17.09.2025 | 2 hours | 0.26 mm/s | Safe |

28.09.2025 | 1.5 hours | 0.19 mm/s | Safe |

Fig. 2Vibration – speed-time results

To assess the impact of vibration on the industrial structures, the methodology outlined in the international standard DIN 4150-3 “Vibration in Buildings. Part 3: Effects on Structures” was used.

4.2. Pile driving tests with pilot drilling

A comprehensive full-scale test program was completed at the construction site of industrial Plant to assess the dynamic impacts of pile driving with pilot drilling. Two tests were conducted from October 2nd to 3rd at distances of 2.5 and 5.0 meters from the vibration source using a 200 mm auger diameter to compare the effectiveness of pilot drilling in reducing vibration loads on the grillage of the industrial building.

5. Discussion

Based on the measurements conducted, a comparative assessment of the effectiveness of various pile driving methods was performed:

– Pile driving without pilot drilling generates significant vibrations near the source (7.8 mm/s at 15 m), but exhibits rapid attenuation with distance.

– Pile driving with a 200 mm diameter pilot drilling generates critical vibrations (12.9 mm/s) at short distances (2.5 m).

For structures that are in the process of hardening and gaining strength, it is critical to preserve the developing crystalline structure of the cement stone. Vibration exceeding a certain threshold can lead to the formation of microcracks and disrupt the adhesion of aggregates to the cement mortar, which subsequently reduces the design characteristics of the concrete. During monitoring, it was found that when using pile driving technology without pilot drilling, the vibration velocity level falls within the acceptable range for fresh concrete at a distance of approximately thirty meters from the source of vibration.

6. Conclusions

Field tests have fully confirmed the significant dynamic impact on building structures and soil foundations that occur during pile driving. The recorded vibration velocity levels show a clear dependence on the distance to the vibration source (pile driving rig) and the pile driving technology used. Comparative analysis of two methods of work (driving without lead drilling, with lead drilling using a 200 mm diameter auger) has clearly demonstrated the high effectiveness of leader drilling technology in reducing vibration loads.

Assessment of the impact on structures that have gained strength. For structures that have reached their standard (grade) strength, the recorded vibration levels at all distances studied did not exceed the maximum permissible value of 10 mm/s, established by the DIN 4150-3 standard for industrial buildings. Consequently, there is no direct threat to the integrity of the load-bearing structures. The values obtained indicate a potential risk to the structural integrity of structures at an early stage of construction. This requires visual inspection of the most critical components upon completion of pile driving work near these structures. Assessment of the impact on freshly laid concrete. Concrete structures in the strength gain stage are most at risk from dynamic impacts. It has been established that:

When working near a structure that has not yet gained strength: restrict (prohibited) percussion work at a distance of less than 38 m without the use of pilot drilling. If work is necessary at a shorter distance, use pilot drilling technology with a 200-250 mm diameter auger, which allows percussion work with a pile driver at a distance of 5 m from the nearest foundation or grillage. If work needs to be carried out at a shorter distance, use lead drilling technology with a 200-250 mm auger diameter, which allows the pile driver to be used at a distance of more than 10 m from the nearest foundation or grillage.

References

-

H. G. Poulos, Pile Foundations. Boston: Springer, 2001.

-

J.P. Schwab and S.K. Bhatia, “Pile Driving Influence on Surrounding Soil & Structures,” Journal of Civil Engineering for Practicing and Design Engineers, Vol. 4, pp. 641–684, 1985.

-

F. E. Richart, J. R. Hall, and R. D. Woods, Vibrations of Soils and Foundations. New Jercey: Prentice Hall Inc, 1970.

-

P. B. Attewell and I. W. Farmer, “Attenuation of ground vibrations from pile driving,” Jornal of Ground Engineering, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 26–29, 1973.

-

B. I. Dalmatov, V. A. Ershov, and E. D. Kovalevsky, “Some cases of foundation settlement in driving sheeting and piles,” in Proceedings of International Symposium on Wave Properties of Earth Materials, pp. 607–613, 1968.

-

G. W. Clough and J. L. Chameau, “Measured effects of vibratory sheetpile driving,” International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences and Geomechanics Abstracts, Vol. 18, No. 2, p. 35, Apr. 1981, https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(81)90911-6

-

D. Mukhanov, “Comprehensive vibration analysis of driven piles at an industrial development site in Kazakhstan: 9 implications for construction safety and engineering practices,” International Journal of Geomate, Vol. 28, No. 129, pp. 39–46, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.21660/2025.129.4811

-

“Engineering survey in construction,” Astana, CS RK 1.02-105-2014, 2014.

-

G. M. Skibin, “Investigation of particularities of the stress-strain state of the sandy basis under loading conditions of rough stamps,” in Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Vol. 1928, No. 1, p. 012065, Jun. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1928/1/012065

-

R. Bazilov, “Report of vibration monitoring,” Kazakhstan, 2025.

-

“Vibrations in construction,” Germany, DIN 4150-3, 2001.

-

G. W. Clough and J.-L. Chameau, “Measured effects of vibratory sheet-pile driving,” Journal of the Geotechnical Engineering Division, Vol. 106, No. 10, pp. 1081–1099, 1980.

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.