Abstract

To optimize the efficiency and noise performance of high-frequency vibrating screens, this study investigates the airflow behavior of lightweight materials during free fall and their impact dynamics on the screening surface. Based on the energy conservation theorem and the characteristics of tobacco screening, a computational model for the air resistance coefficient was derived. KT board specimens were employed as experimental substitutes for tobacco leaves to examine the effects of porosity and geometric dimensions on descent velocity and air resistance. The results indicated that materials with higher porosity exhibited greater descent velocities and lower air resistance, whereas larger geometric dimensions lead to increased aerodynamic drag and higher resistance coefficients. Furthermore, field operational modal analysis revealed that the sieve plate exhibited subharmonic resonances within the 9.9-10 Hz and 20-30 Hz frequency bands under nonlinear excitation. These findings could provide theoretical and data support for structural optimization aimed at noise reduction and screening efficiency enhancement.

Highlights

- To optimize the efficiency and noise performance of high-frequency vibrating screens, this study investigates the airflow behavior of lightweight materials during free fall and their impact dynamics on the screening surface by modal analysis.

- Based on the energy conservation theorem and the characteristics of tobacco screening, a computational model for the air resistance coefficient was derived.

- The results indicated that materials with higher porosity exhibited greater descent velocities and lower air resistance, whereas larger geometric dimensions lead to increased aerodynamic drag and higher resistance coefficients.

- It is recommended to improve the sieve plate material to significantly increase its natural frequency and reduce its mass. This approach can effectively control noise and minimize the impact of the screening machine's vibration on the building structure.

1. Introduction

The efficient operation of the tobacco leaf screening system plays a crucial role in improving the production efficiency of cigarette factories [1]. During the high-frequency vibration screening process, tobacco leaves with different varieties, porosity, and moisture levels experience varying air resistance, which affects the screening efficiency at different stages of the production line [2].

The air resistance coefficient is a key parameter used to characterize the effect of air resistance on an object or structure moving through the air, particularly in high-speed motion. Accurately determining the air resistance coefficient is essential in the design of high-frequency vibrating screens, as it directly impacts screening efficiency and energy consumption. Optimizing the screening process to enhance efficiency while achieving energy-saving and low-carbon goals is a critical factor in process improvement [3]. The main technical contents of the relevant standards of high frequency vibrating screen in China are elaborated [4].

Currently, research on air resistance effects is more prevalent in defense, military, and civilian applications, particularly in high-speed transportation vehicles such as high-speed railways and aircraft, as well as in regions with complex geographical and atmospheric conditions. For example, Y. Chen [5] et al. conducted a three-dimensional numerical simulation to analyze the effect of air resistance on high-speed subway trains. Their findings indicated that as the train approached the vertical shaft, the air resistance coefficient continuously decreased, with the resistance concentrating at the rear of the train during steady motion. Li [6] et al. developed a three-dimensional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model for high-speed trains and found that the leading car was the primary noise source. Cao [7] et al. employed numerical simulation to analyze the gas flow field inside a concentric tube during missile launch, providing a reference for optimizing concentric tube design. Wang [8] et al. constructed a jet motion model that accounts for air resistance, proposing a feasible wind-resistant firefighting scheme for compressed air foam cannons under harsh wind conditions. Deng [9] et al. investigated the effects of tunnel length, slope type, gradient, altitude, and train speed on four air resistance indicators for high-speed trains passing through high-altitude railway tunnels: average train air resistance, maximum train air resistance, average tunnel air resistance coefficient, and maximum tunnel air resistance coefficient.

In contrast, limited research has been conducted on the influence of air resistance coefficients on the screening efficiency of high-frequency vibrating screens and the vibrational response of the screen panels. Pany [10] et al. had studied the supersonic panel flutter analysis of flat plates and curved plates with different edge boundary conditions. The linear piston theory was used to evaluate the aerodynamic loads. The solution of a complex eigenvalue problem was formulated according to Hamilton’s principle. Members of the research group, Pang [11] et al. and Ren [12] et al. used MATLAB simulations to analyze the displacement and velocity of tobacco leaves in motion, comparing results with cases where air resistance was not considered. However, there remains a lack of systematic research on how the air resistance coefficient varies with tobacco leaf characteristics and how these variations impact screening efficiency and screen panel vibration. Investigating the effects of tobacco leaf size, porosity, and other constitutive parameters on air resistance and integrating these findings into the structural optimization of high-frequency vibrating screens align with the scientific and technological innovation goals of new-quality productivity in the tobacco industry.

With the implementation of the national “carbon peaking” and “carbon neutrality” policies, enterprises can reduce their carbon emissions and accumulate carbon credits by adopting advanced energy-saving technologies, improving production processes, and optimizing energy structures. As a result, the application of high-frequency vibrating screens in the tobacco industry is expected to expand. Further research on the factors influencing air resistance during tobacco leaf screening is crucial for improving screening efficiency. However, experimental studies on air resistance in tobacco leaf screening remain limited. The national standards for vibrating screen design in the tobacco industry only specify screening efficiency requirements, stating that efficiency is related to factors such as tobacco variety and porosity. The specific design requirements should align with the working conditions specified by the end user.

During the tobacco screening process, variables such as drop height, ambient airflow, tobacco leaf size, and porosity influence the screening efficiency of different vibrating screens, with a particularly significant impact on high-frequency vibrating screens. These factors are indispensable for future research on the development of high-frequency vibrating screens and the optimization of screening production lines.

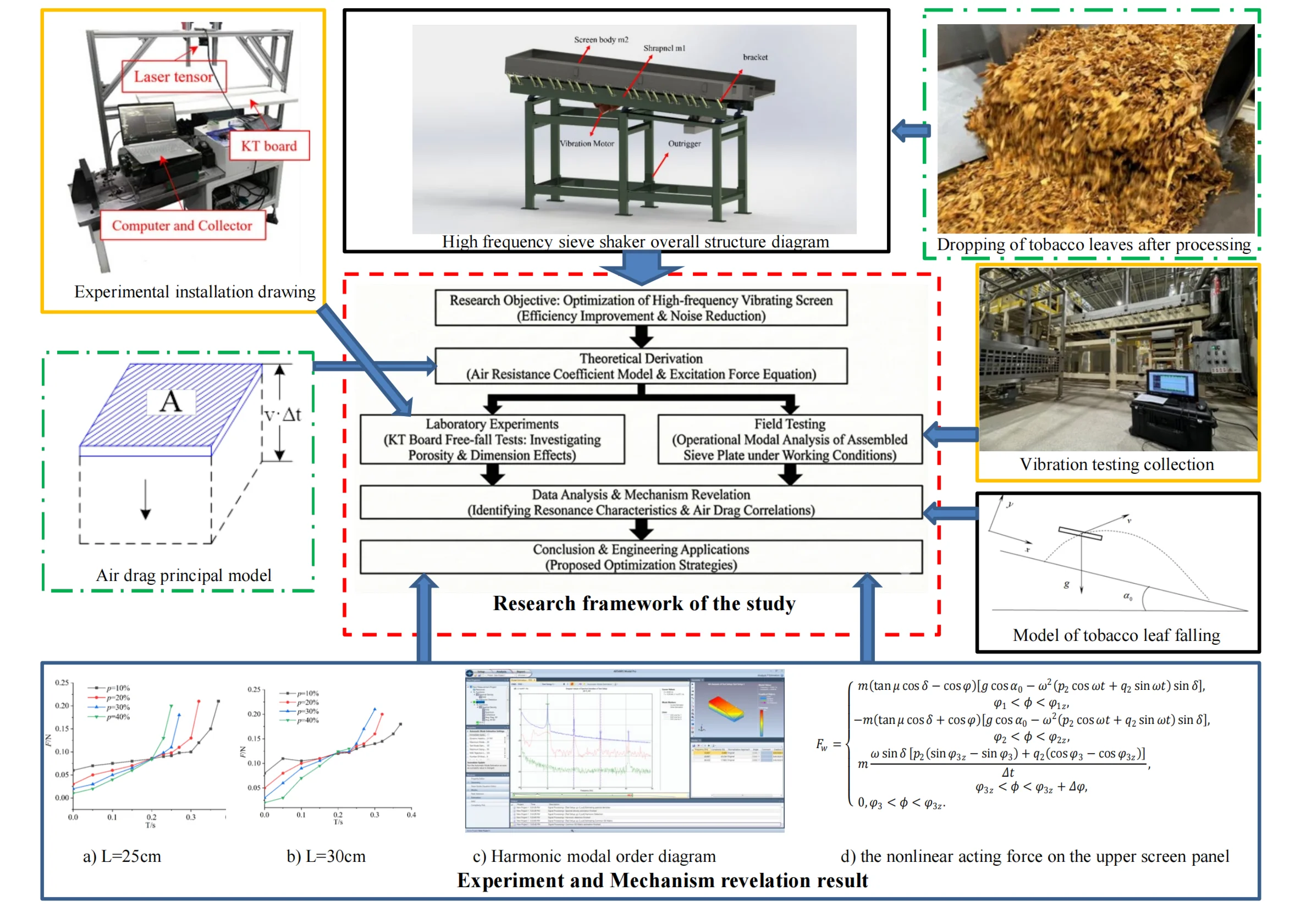

The research framework of this study is illustrated in Fig. 1. Drawing on research methods such as those employed by Liang [13] et al., who used a free-fall model to determine the air resistance coefficient, and Yuan [14] et al., who conducted simulations to analyze air resistance coefficients, this study aims to simulate material screening conditions using KT board specimens. The novelty of this work lies in three main aspects: (i) experimentally determining the air resistance coefficient of lightweight particulate materials and assessing its correlation with porosity and dimensions; (ii) deriving a theoretical model for the excitation force exerted by falling materials; and (iii) conducting experimental modal analysis to determine the natural frequency of the assembled sieve plate. By comprehensively analyzing these factors, this research reveals the mechanism of resonance and noise generation, providing a theoretical basis for optimization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 derives the theoretical model for the air resistance coefficient of lightweight particulate materials. Section 3 details the experimental design using KT board specimens and analyzes the effects of porosity and dimensions on descent velocity and air resistance. Section 4 presents the modal analysis of the high-frequency vibrating screen under operating conditions. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the conclusions and implications for industrial applications.

Fig. 1Research framework of the study

2. Research method for testing air resistance of light particulate materials tobacco dropping

2.1. Derivation of Light particulate materials air resistance coefficient

To address the need for precise optimization of screening parameters, it is necessary to first establish a theoretical basis for the interaction between the material and airflow. In this section, we derive the computational model.

In the process of actively promoting technological innovation across industries, gaining core competitiveness requires conducting relevant theoretical research and proposing corresponding improvement measures and solutions to existing problems [15]. Cai [16] et al. had numerical simulation of air resistance of light materials. But the accumulation of theoretical knowledge is essential for addressing each original problem.

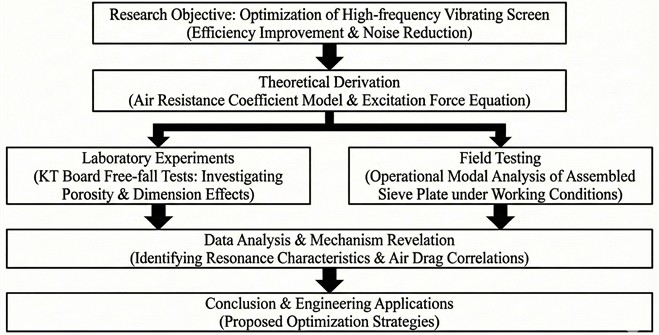

Fig. 2Model and material

a) Air drag principal model

b) Light material

As shown in Fig. 2(a), the thin plate undergoes free-fall motion with an area of and a velocity of . Considering an infinitesimal time interval , the air density is set as under normal temperature and pressure conditions. Given the incompressibility of air, during the time interval , the gravitational force acting on the thin plate performs work on a cylindrical air element with a mass of , resulting in the following kinetic energy of the air element:

According to Newton’s third law, the forces exerted by two interacting bodies are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. The force exerted by the air that resists the downward motion of the thin plate is the air resistance acting on the plate. Thus, the work done by the air resistance can be expressed as:

Since the lightweight thin plate moves at a relatively low speed, the heat loss due to friction during motion is negligible. Its motion satisfies the law of energy conservation. Based on , the expression for air resistance can be derived as:

Based on the well-established theories and research findings in the automotive field regarding air resistance and drag coefficient, the following expression can be derived. dimensionless parameter is introduced, which is related to the shape of the lightweight falling object:

In the above equation, represents the air resistance coefficient, which varies depending on the falling object and its surface characteristics. During the free-fall process of the thin plate, data is continuously recorded using a laser ranging acquisition system. Subsequently, data processing is performed to obtain the velocity and acceleration curves of the falling plate throughout its motion. Here, denotes the instantaneous displacement of the falling plate, and represents its instantaneous acceleration, expressed as:

According to Newton’s Second Law, the formula for calculating air resistance can be expressed as:

where represents the gravitational force of the thin plate, and represents the inertial force of the thin plate, is the mass of the thin plate.

Substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (4), the air resistance coefficient formula for the falling thin plate can be expressed as:

where, 1.29 kg/m3 represents the air density under standard conditions.

Fig. 2(b) displays the KT board specimen used in this study. The KT board consists of a polystyrene (PS) core produced through a foaming process. It is characterized by its light weight, resistance to deterioration, and ease of processing, which allows for precise control over porosity and mass distribution. Similar to tobacco leaves, it serves as an ideal model for lightweight and thin particulate materials.

2.2. Experimental testing and analysis of Light particulate materials air resistance

The experimental measurement of air resistance for lightweight falling objects, such as tobacco leaves, is the most direct and reliable method for studying their motion characteristics. In this experiment, KT boards were used as substitutes for tobacco leaves to investigate the effects of material porosity and geometric dimensions on air resistance during free fall. A linkage device was employed to release the lightweight boards while a laser ranging data acquisition system recorded the motion. Subsequently, data regression processing was conducted using MATLAB to indirectly determine velocity and acceleration [17]. The entire testing process was conducted under stable airflow conditions in the laboratory [18], and the air resistance and its coefficient were obtained using the air resistance coefficient calculation Eq. (7). Finally, the experimental results were used to analyze the impact force of falling tobacco leaves on the sieve plate.

3. Application effects of Light particulate materials

3.1. Experimental design

Tobacco leaves exhibit characteristics such as being lightweight, thin, porous, and irregularly shaped. After re-drying, their density ranges from 0.90 to 1.22 g/m3, which is relatively close to the density of KT boards, which fall within 1.00 to 1.40 g/m3. Moreover, KT boards allow precise control of porosity and dimensions, facilitating experimental data analysis and comparison. Therefore, lightweight KT boards were selected for the study.

To ensure the reproducibility of the experiments, strict environmental controls were implemented. The laboratory temperature was maintained at 25±2 °C, and the relative humidity was controlled at 50±5 % to minimize the impact of air density variations on the free-fall motion. The KT board specimens were precision-cut using a computer numerical control (CNC) cutter to ensure dimensional accuracy (± 0.1mm) and to maintain consistent edge quality, thereby reducing aerodynamic interference caused by rough edges.

Fig. 2(b) presents a KT board measuring 40 cm × 40 cm with a porosity of 40 %. Four groups of square thin plates were designed and fabricated, with side lengths of 25, 30, 35, and 40 cm. Each group corresponds to four porosities : 10 %, 20 %, 30 %, and 40 %. Including additional backup KT boards, a total of 24 boards were prepared to ensure uniform horizontal mass distribution and stable free-fall motion while maintaining consistent mass within each group.

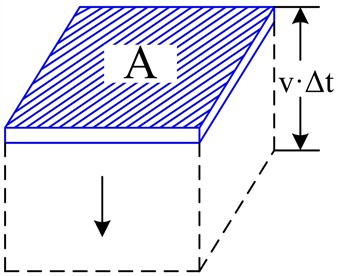

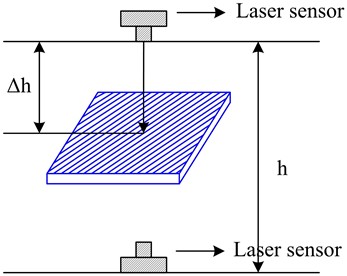

The laser sensor used for displacement measurement during the KT board’s free-fall is detailed in Table 1. The experiment simulates the movement of tobacco leaves from the discharge outlet to the screening surface, where they are influenced by gravity and rebound airflow near the screening surface, allowing for an in-depth investigation of their motion behavior.

Table 1Parameters of sensor

Type | Maximum measurement center distance (mm) | Measuring range (mm) | Maximum resolution (mm) | Maximum acquisition frequency (Hz) |

HG-C1800 | 1000 | ±400 | 1 | 1000 |

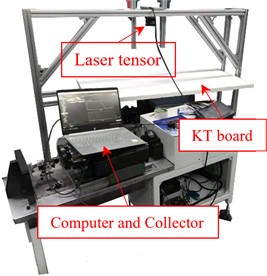

The experimental model is shown in Fig. 3(a) and 3(b). The experiment was conducted under laboratory conditions. A laser displacement sensor was activated, and the KT board was fixed at the zero-point release panel. The KT board was released via a linkage switch, simultaneously triggering data acquisition by the laser displacement sensor. The experiment was carried out under normal indoor ventilation conditions to simulate the free-fall motion of tobacco leaves, with different KT board models tested sequentially.

Fig. 3(b) illustrates the experimental support structure for simulating the screening surface. The setup consists of an aluminum alloy frame, a laser sensor, a linkage switch, a bottom baffle support, and a laptop data acquisition system.

Fig. 3Experiment setup for lightweight boards. (Experiment in Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, Hebei, China, 2024)

a) Experimental diagram

b) Experimental installation drawing

3.2. Experimental data analysis of Light particulate materials air resistance

The free-fall method was used to measure the air resistance coefficient. By recording the displacement data of KT boards with different combinations of side lengths and porosity during the falling and screening process, the original data was analyzed using Origin to generate curves. MATLAB was employed to calculate and solve for parameters such as velocity, acceleration, and air resistance coefficient during the descent [19].

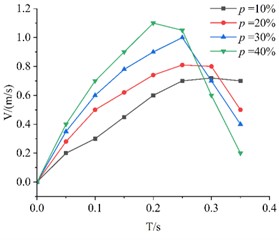

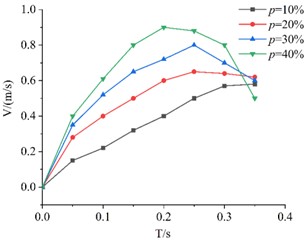

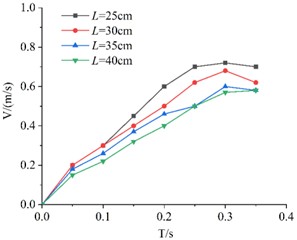

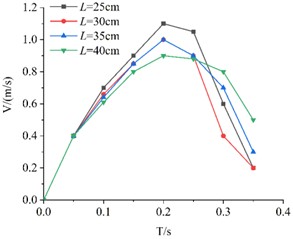

3.2.1. Influence of porosity on the screening descent velocity

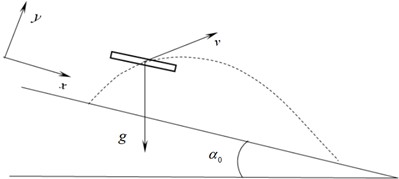

To facilitate data comparison in the graphs and make the overall trend of each curve more distinct, the plotting time is uniformly set to 0.4 seconds. As shown in Fig. 4, KT boards with the same edge length but different porosities exhibit an initial increase in velocity followed by a decrease during descent. When approaching the sieve plate surface, the velocity decreases due to the influence of rebound airflow, which increases air resistance.

Comparative analysis indicates that for thin plates with the same edge length, a higher porosity results in a shorter descent time, a greater average velocity, and a higher peak velocity. The experimental results strongly validate the derived Eq. (7) for calculating air resistance coefficients. With constant density across all test specimens, the plate exhibiting the fastest drop velocity demonstrated the highest porosity and consequently the least air resistance, showing the most significant velocity change. This phenomenon became particularly pronounced in thinner plates with smaller dimensions, demonstrating how size effects influence porosity and air resistance. Key parameters require comprehensive consideration and simulation calculations. Vibration significantly affects the synchronization of vibrating screen movements.

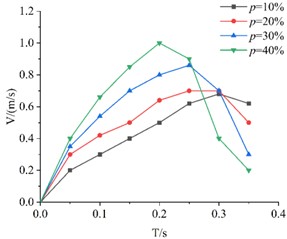

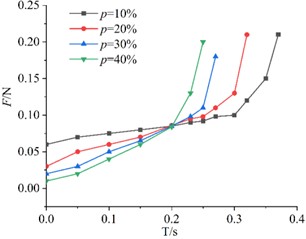

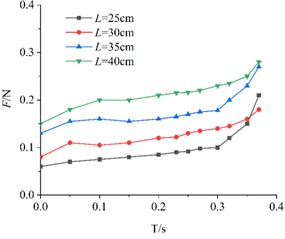

3.2.2. Influence of porosity on Light particulate materials air resistance

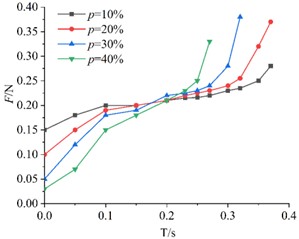

To investigate the effect of porosity on air resistance during the descent process, time-air resistance curves were plotted for KT board models with the same edge length but different porosities, as shown in Fig. 5.

From the four subplots in Fig. 5, it can be observed that the air resistance acting on the KT board model increases with time during its descent. The falling time of KT board with lower porosity is short. At 0.2 s, the air resistance curves for the four porosity levels intersect at a common point. Before this intersection, at any given moment, board with lower porosity experience greater air resistance, whereas those with higher porosity experience lower resistance. After the intersection point (approximately 0.2 s), the aerodynamic behavior diverges significantly. KT boards with higher porosity descend faster and approach the sieve plate earlier. Consequently, they encounter the rebound airflow from the sieve surface sooner, leading to a sharp and early increase in air resistance. In contrast, boards with lower porosity descend more slowly and experience this resistance spike later. Therefore, in the late stage of descent, the measured air resistance for high-porosity boards appears higher because they are interacting with the ground effect zone while low-porosity boards are still in free fall.

Fig. 4Descent velocity curves of KT boards with different porosities over time

a) 25 cm

b) 30 cm

c) 35 cm

d) 40 cm

Fig. 5Air resistance variation of KT boards with different porosities (same edge length)

a) 25 cm

b) 30 cm

c) 35 cm

d) 40 cm

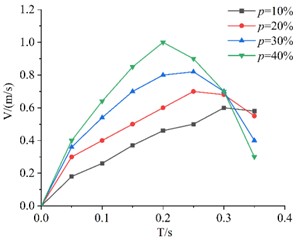

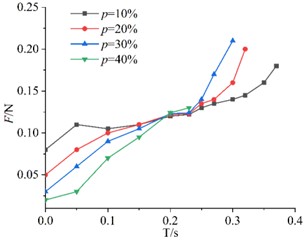

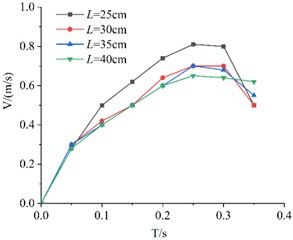

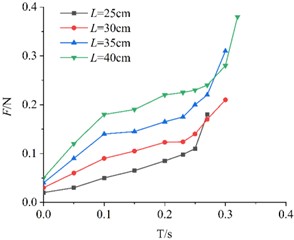

3.2.3. Influence of edge length on descent velocity

The experimental data were imported into Origin, and a comparative plot of descent velocity for KT boards with the same porosity but different edge lengths was generated, as shown in Fig. 6.

From Fig. 6, it can be observed that the velocity of all four boards initially increases and then decreases during descent. Before reaching the peak velocity, the influence of the upper sieve surface is minimal. However, after reaching the peak velocity, the KT boards begin to decelerate due to the effect of the upper sieve surface. The velocity variation pattern remains consistent across different KT boards with the same porosity. It can be observed that before reaching peak velocity, boards with larger edge lengths generally exhibit lower descent velocities at any given moment due to increased surface area and air drag. Furthermore, the velocity variation pattern remains consistent across different edge lengths: the board accelerates until it encounters the resistance effects near the sieve surface. Comparing the curves, larger boards (e.g., 40 cm) show a more gradual velocity increase compared to smaller boards (e.g., 25 cm), confirming that geometric size significantly influences the descent dynamics.

Fig. 6Velocity comparison of different side length board with the same porosity

a) 10 %

b) 20 %

c) 30 %

d) 40 %

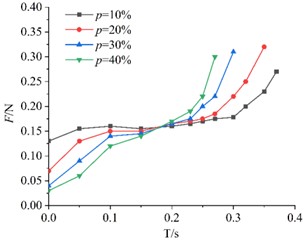

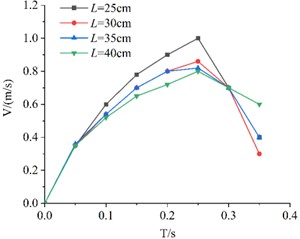

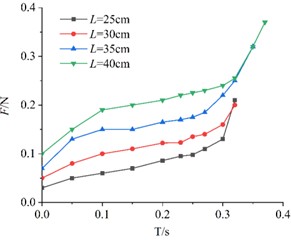

3.2.4. Influence of edge length on Light particulate materials air resistance

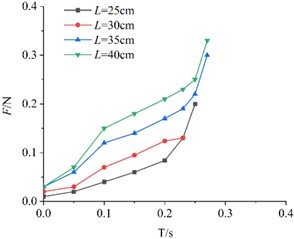

As shown in Fig. 7, KT boards with the same porosity but different edge lengths experience gradually increasing air resistance during descent. In the early stage of descent, the resistance increases slowly. However, in the later stage, as the plates approach the baffle, air resistance grows significantly and rapidly.

From Fig. 7, it can be observed that the air resistance variation pattern remains generally consistent across KT board models with different porosities. Specifically, the larger the size of the square KT board model, the greater the air resistance it experiences during descent.

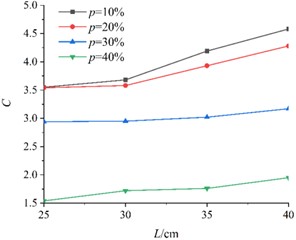

3.2.5. Influence of edge length and porosity on air resistance coefficient

Using the air resistance coefficient Eq. (7), the air resistance coefficients for different KT board models with varying edge lengths and porosities during descent were calculated, as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 7Comparison of air resistance of models with same porosity and different side lengths

a)10 %

b)20 %

c)30 %

d) 40 %

From the variation curves of air resistance coefficient with KT board size and porosity in Fig. 8, combined with the expression of air resistance coefficient in Eq. (7), it can be concluded that in the presence of a baffle: The larger the edge length of the KT board, the greater the air resistance coefficient during the screening descent process; The smaller the porosity, the greater the air resistance coefficient. During screening, the impact force of tobacco leaves on the sieve plate is a random nonlinear excitation.

Fig. 8Air drag coefficient as a function of edge length and porosity

3.3. Analysis of the impact of Light particulate materials material falling on the resonance of high-frequency vibrating screens

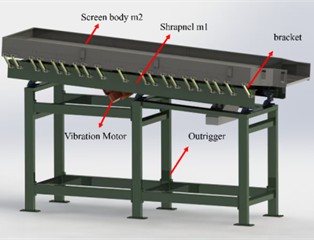

High-frequency vibrating screens are currently in a rapid development phase within the tobacco industry, with broad application prospects and increasing customization needs. The overall structure of the high-frequency vibrating screen is shown in Fig. 9(a), two high-frequency motors are installed on the lower frame, and the amplitude of the eccentric excitation force is adjusted by modifying the position of the internal eccentric mass blocks, while the excitation force frequency is controlled by varying the rotational speed. The vibration amplitude of the upper and lower screening plates is controlled by adjusting the number, stiffness, size, and shape of resin elastic elements between them, as well as by designing the relative mass and structural configuration of the two plates.

To mitigate the harmful vibrations transmitted to the factory floor, particularly when the vibrating screen is installed on the second floor or higher, damping supports are designed and tested for optimal selection. Currently, imported ROSTA elastic supports are widely used, but their fixed vibration characteristics limit their adaptability. Pany [20] et al. observed that the lowest frequency can be found out at the lower bound of first propagation surface, by choosing an optimum periodic angle of curved panel. In some environments, their performance is suboptimal, slowing down the customization of high-frequency vibrating screens. Key technical challenges include determining the damping and vibration isolation parameters of elastic supports, selecting appropriate materials, and optimizing the support arrangement. Addressing these issues is essential for enhancing the large-scale design, customization, and proprietary development of high-frequency vibrating screens. In the tobacco screening process, the falling of tobacco leaves can be simulated as lightweight plates with varying porosities dropping onto the sieve plate. To prevent material accumulation and improve efficiency, the swing amplitude or vibration frequency of the sieve plate is typically increased. However, this often leads to increased noise and significant machine vibration. Therefore, reasonable regulation of these parameters is essential to balance efficiency with operational stability.

Fig. 9Overall structure diagram of the high-frequency sieve shaker and the motion model for tobacco leaf falling and throwing

a) High frequency sieve shaker overall structure diagram

b) Model of tobacco leaf falling and throwing motion

The research team has accumulated several years of study and has established and derived the vibration control equation for the dual-mass high-frequency vibrating screen. Pang [21] et al. had studied nonlinear harmonic resonance analysis of vibrating screen. Ma [22] et al. had studied on vibration characteristics and parameter optimization of double-mass linear vibrating screen. Considering the actual working conditions where tobacco leaves fall onto the upper screening plate as a nonlinear excitation force, the theoretical derivation and calculation indicate the potential occurrence of nonlinear harmonic resonance in this type of vibrating screen. The force exerted by the falling tobacco leaves on the screening plate is a random nonlinear excitation. Based on previous research findings, Fig. 9(b) illustrates the throwing motion model of the tobacco leaves. According to D’Alembert’s principle, the equation of motion for the material in the y-direction is given by:

Just before the throwing motion occurs, = 0, the phase angle at which the material begins its throwing motion is obtained as:

where is referred to as the throwing index.

During the falling process, when the tobacco leaves have not yet contacted the screen panel, the acting force is zero. Using this boundary condition, the nonlinear acting force on the upper screen panel of the high-frequency vibrating screen is obtained as:

where, represents the rotor angle of the motor when the tobacco leaves slide forward, and represents the rotor angle of the motor when the tobacco leaves slide backward. And represents the angle between the vibration direction and the horizontal direction, denotes the vibration amplitude (which is adjustable), and is the circular frequency of the vibrating screen.

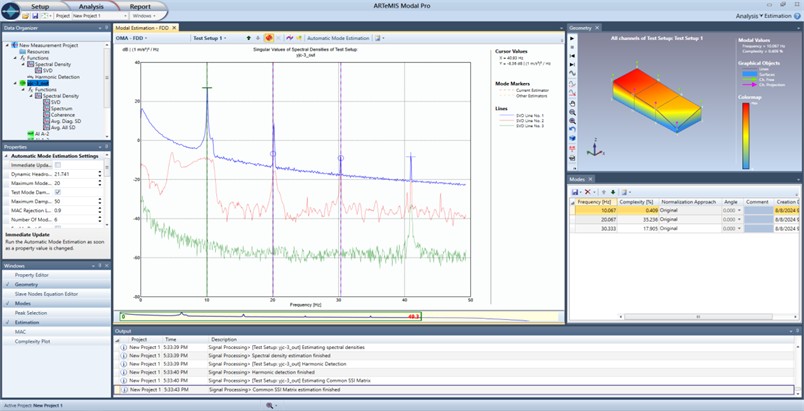

When considering the nonlinear force exerted by tobacco leaves, the amplitude of the upper screen plate decreases, which slows down the material passing speed and reduces screening efficiency. Yu [23] et al. investigated the synchronized motion characteristics of a four-exciting motor-driven two-body vibrating system to determine its engineering applicability. They derived the system's differential equations using the Lagrange equation. Pany [24] et al. presented a method of analysis to determine multi-supported curved panel frequencies using high-precision triangular finite element. The nonlinear vibration significantly affects the synchronization of vibrating screen movement. The upper screen plate exhibits harmonic vibrations accompanied by noticeable high-frequency noise, while the amplitude of the lower support structure increases. Based on feedback regarding screen plate noise issues from different models of high-frequency vibrating screens used in Chuzhou, Bijie, and Zunyi tobacco factories, the Austrian DEWESoft vibration acquisition system was employed for testing. The testing setup is shown in Fig. 10. A hammer force sensor and 16 acceleration sensors were used, and environmental excitation methods were applied with ARTeMIS Modal Pro modal analysis software to conduct rigid-body modal tests on the double-layer vibrating screen. Additionally, elastic-body modal tests were performed separately on the upper and lower screen bodies.

Fig. 10High frequency double-sieve shaker test field diagram. (Test at Chuzhou Cigarette Factory, Anhui, China, 2024.6.15)

a) Vibration testing collection

b) Dropping of tobacco leaves after processing

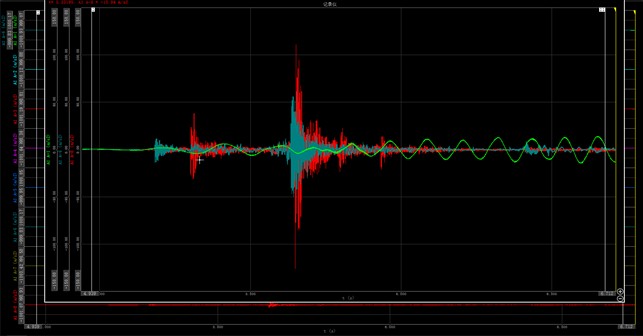

The analysis revealed that during normal startup and operation, an instantaneous random excitation of approximately 9.8 Hz occurs, as shown in the impact curve in Fig. 11. As the motor speed increases, the vibrating screen quickly enters its normal working state, and the vibration amplitude of the support legs significantly decreases, remaining within the industry’s standard operating range. The blue curve represents the horizontal impact signal on the support legs, while the red curve corresponds to the vertical impact signal.

Fig. 11Comparison of vibration acceleration amplitude signal during starting of vibrating screen

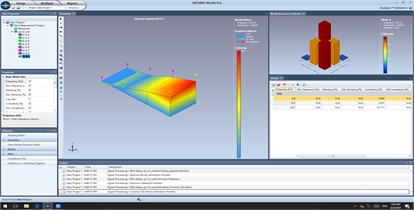

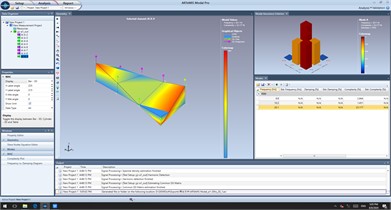

Fig. 12Vibration modal analysis of upper tank body

a) Harmonic modal order diagram

b) First-order primary resonance

c) 1/2 subharmonic resonance

During the tobacco material screening process, tests were conducted with the variable-frequency motor operating at 12.5 Hz, which corresponds to a motor speed of 750 r/min. Modal analysis determined that the first in-plane primary resonance frequency of the upper screen plate falls within the range of 9.9-10 Hz, as shown in Fig.12(b). However, in the modal order determination diagram shown in Fig. 12(a), harmonic vibrations with amplitude attenuation were observed at frequencies of 20 Hz and 30 Hz. Specifically, at 20 Hz, a noticeable torsional vibration occurred, as illustrated in Fig. 12(c). This further validates the theoretically derived conclusion that the high-frequency vibrating screen, under external nonlinear excitation, exhibits nonlinear harmonic vibration. Additionally, it confirms that the upper screen plate generates a certain level of noise during operation, providing essential references for the subsequent optimization of high-frequency vibrating screen design. The optimal selection of physical characteristics for lightweight falling materials is based on minimizing air resistance and reducing the descent time to the sieve plate, thereby significantly improving screening efficiency. Through modal analysis of the sieve plate, the excitation frequency caused by the continuous falling of lightweight materials must be controlled to avoid the ranges of 9.9-10 Hz and 20-30 Hz. This prevents resonance with the sieve plate’s natural frequencies, which would otherwise compromise the equipment’s service life.

4. Conclusions

By applying the principle of energy conservation and considering the characteristics of tobacco screening, a computational model for the Light particulate materials air resistance coefficient of falling tobacco leaves was derived. Through an orthogonal experimental comparison, the effects of porosity and size of lightweight falling objects on their falling velocity, air resistance, and air resistance coefficient during high-frequency vibrating screen screening were investigated. Through systematic experimental research, we further validated the accuracy of the numerical simulation results obtained by research group member Cai [16] et al., who used ANSYS/Fluent to simulate the unsteady process of material screening and falling. The conclusions drawn from this experimental study are consistent with those derived from the numerical simulations. Additionally, vibration modal tests of the screen plate under working conditions were conducted. The main findings are as follows:

1) For thin plate models with the same edge length, a larger porosity results in a greater falling velocity and acceleration, while the air resistance coefficient decreases. For thin plates with the same porosity, a larger edge length leads to a lower falling velocity and acceleration, whereas a longer edge length increases the air resistance and air resistance coefficient.

2) The upper screen plate affects the falling velocity of lightweight material models, slowing their descent and increasing air resistance. As the material approaches the baffle, the Light particulate materials air resistance and air resistance coefficient increase.

3) During the screening process, the impact of tobacco leaves on the screen plate acts as a random nonlinear excitation. A reduction in the amplitude of the upper screen plate leads to a decrease in the material flow rate and screening efficiency. Therefore, when designing the amplitude of high-frequency vibrating screens, a 10 % increase should be considered.

4) During the tobacco material flow period, the falling process continuously applies nonlinear excitation to the upper screen plate. Under the influence of external nonlinear excitation, the high-frequency vibrating screen exhibits nonlinear harmonic vibration, leading to noise generation from the upper screen plate. Measures such as modifying the screen plate structure, improving processing techniques, and using advanced composite materials can help achieve energy savings and noise reduction, providing valuable references for the optimization of high-frequency vibrating screens.

5) The tobacco screening process can be simulated as lightweight plates with varying porosities falling onto a sieve plate. To prevent material accumulation and improve efficiency, the swing amplitude or vibration frequency of the sieve plate is typically increased. However, this often leads to increased noise and significant machine vibration. Therefore, reasonable regulation of these parameters is essential. It is recommended to improve the sieve plate material to significantly increase its natural frequency and reduce its mass. This approach can effectively control noise and minimize the impact of the screening machine's vibration on the building structure.

Factors such as the size, porosity, and moisture content of tobacco leaves which is one of the Light particulate materials directly impact screening efficiency. Particularly for high-frequency vibrating screens, results indicate that at a distance far from the bottom baffle, the motion of the lightweight plate is not significantly affected by the bottom airflow. However, after reaching maximum velocity, the airflow generated by the bottom sieve surface exerts a greater influence, causing the plate to enter a deceleration phase. When the lightweight plate is very close to the sieve surface, the resistance from compressed air increases rapidly. This paper identifies these patterns experimentally; future work will deduce theoretical models considering the influence of eddy currents behind the lightweight plate for further research and experimental verification. The research results not only apply to tobacco leaves but also provide theoretical models and reference data for calculating air resistance and improving screening efficiency for other lightweight materials. These findings can serve as essential reference indicators for optimizing screening processes and developing screening equipment.

References

-

W. Kuang, “Analysis of material vibration screening process and its efficient way,” (in Chinese), China Plant Engineering, No. 9, pp. 209–210, May 2019.

-

L. Peng et al., “A review on the advanced design techniques and methods of vibrating screen for coal preparation,” Powder Technology, Vol. 347, pp. 136–147, Apr. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2019.02.047

-

H. S. Zhao and D. D. Yin, “The current situation and main technical content analysis of high-frequency vibrating screen standard in China,” China Coal, Vol. 46, No. 6, pp. 69–76, Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/10.19880/j.cnki.ccm.2020.06.011

-

H. S. Zhao, Y. Ding, M. Li, and H. L. Wang, “Current status in research of standards of high-frequency vibrating screen and proposed countermeasures,” Coal Preparation Technology, Vol. 4, pp. 1–7, Oct. 2020, https://doi.org/10.16447/j.cnki.cpt.2020.04.001

-

Y. Chen, C. H. Zhou, and X. F. Zhang, “Numerical simulation study on aerodynamic drag of high-speed subway train in interval tunnel,” Mechanical Science and Technology for Aerospace Engineering, Vol. 40, No. 12, pp. 1961–1965, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.13433/j.cnki.1003-8728.20200296

-

K. X. Li, “Numerical simulation of aerodynamic drag and aerodynamic noise of high-speed train,” (in Chinese), Science and Technology Innovation, Vol. 20, No. 32, pp. 89–91, Nov. 2021.

-

L. Cao, “Research on the combustion flow field in the concentric canister launcher during missile launch,” (in Chinese), Ship Electronic Engineering, Vol. 42, No. 6, pp. 155–158, Aug. 2022.

-

J. Y. Wang and H. H. Jing, “Study on wind-resistance characteristics of jet motion control in compressed air foam system,” Journal of Machine Design, Vol. 41, No. 8, pp. 45–52, Aug. 2024, https://doi.org/10.13841/j.cnki.jxsj.2024.08.011

-

H. Deng, Y. C. Wan, and Y. G. Mei, “Variation pattern in air resistance of a train passing through long and extra-long high-speed railway tunnels in plateau areas,” (in Chinese), Tunnel Construction, Vol. 44, No. 7, pp. 1491–1501, Aug. 2024.

-

C. Pany, “Panel flutter numerical study of thin isotropic flat plates and curved plates with various edge boundary conditions,” Politeknik Dergisi, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 1467–1473, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.2339/politeknik.1139958

-

J. F. Pang et al., “Motion analysis of vibrating screening material considering the effect of air resistance,” Chinese Quarterly of Mechanics, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 783–794, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.15959/j.cnki.0254-0053.2020.04.018

-

Y. L. Ren, “Dynamic analysis and parameter optimization of double-body high-frequency vibrating screen,” (in Chinese), Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, May 2018.

-

B. Liang and H. Y. Gan, “Measurement of air resistance coefficient by means of free falling body in laboratory,” Journal of Baise University, Vol. 22, No. 6, pp. 58–60, Apr. 2009, https://doi.org/10.16726/j.cnki.bsxb.2009.06.010

-

Y. Yuan and Y. H. Zhang, “Computational simulation of air resistant coefficient for S-blade,” (in Chinese), Journal of Anhui University of Technology (Natural Science), Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 246–249, Jul. 2011.

-

Y. Z. Zhang, Numerical Simulation Technology of Automobile Aerodynamics. (in Chinese), Beijing: Peking University Press, 2011.

-

Y. T. Cai, “Numerical simulation of air resistance of light materials,” (in Chinese), Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, 2021.

-

T. Wang, “Experimental study on air resistance of light material screening,” (in Chinese), Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, 2021.

-

J. Pang, X. Liu, Y. Cai, and G. Du, “Controlled experimental research and model design of double-layer high-frequency vibrating screen machine,” Journal of Vibroengineering, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 298–315, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2020.21639

-

J. F. Pang, “Study on vibration characteristics of double body high frequency vibrating screen and material movement,” (in Chinese), Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, 2020.

-

C. Pany, S. Parthan, and M. Mukhopadhyay, “Wave propagation in orthogonally supported periodic curved panels,” Journal of Engineering Mechanics, Vol. 129, No. 3, pp. 342–349, Mar. 2003, https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0733-9399(2003)129:3(342)

-

J. F. Pang, “Nonlinear harmonic resonance analysis of vibrating screen,” (in Chinese), Chinese Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 37, No. 6, pp. 2657–2663, Dec. 2020.

-

G. Y. Ma, “Study on vibration characteristics and parameter optimization of double-mass linear vibrating screen,” (in Chinese), Yanshan University, Qinhuangdao, 2019.

-

L. Yu, “Simulation and test of synchronous motion characteristics of four-motor driven two-body vibrating system,” (in Chinese), Journal of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, pp. 1–12, Aug. 2025.

-

C. Pany, S. Parthan, and M. Mukhopadhyay, “Free vibration analysis of an orthogonally supported multi-span curved panel,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 241, No. 2, pp. 315–318, Mar. 2001, https://doi.org/10.1006/jsvi.2000.3240

About this article

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation General Program (61873227), Central Government-funded Project for Guiding Local Scientific Development (246Z1819G) and China National Tobacco Corporation’s “Development of Dual-structure Resonant High-frequency Vibrating Screen” project (Y202206).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Xiaoman Liu: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, writing-original draft preparation. Yang Wang: writing-review and editing, methodology, resources. Jianyu Chang: writing-review and editing, software, formal analysis.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.