Abstract

This review explores the possibility of enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of Industrial Gas turbine Performance testing by critically assessing the traditional methods, their limitations, and how modern technologies can be used to complement the existing traditional testing approaches, optimize data acquisition, and predict operational failures. A systematic and comprehensive search strategy was employed to identify relevant academic and industry literature. Studies on traditional testing practices were reviewed to highlight their constraints, while researches involving the application of emerging technologies for performance diagnostics were also reviewed to illustrate their benefits. Findings show that measured data such as turbine inlet temperature, compressor pressure ratio, exhaust temperature, fuel flow, shaft speed, and vibration remain essential for both traditional and AI-enhanced methods. These parameters, typically obtained through standardized testing procedures, provide the foundational input for AI models such as machine learning algorithms and digital twins. The study revealed that AI technologies thrive in data-rich, repeatable environments by enhancing processes like instrumentation, data logging, and normalization. The study also revealed that machine learning, deep learning, artificial neural networks, and digital twins can be used for more effective planning, reduce redundant testing, and mitigate delays caused by variable factors like weather or load conditions.

Highlights

- Traditional methodologies for measuring critical gas turbine performance indicators, such as power output and efficiency, remain fundamental but face limitations in precision and adaptability under diverse operating conditions.

- The integration of emerging technologies with traditional methods has shown great potential in advancing industrial gas turbine performance testing.

- AI-driven solutions enable predictive analytics, automated anomaly detection, and optimization of operational parameters, thereby significantly reducing downtime and maintenance costs.

- To achieve optimized performance testing and further minimize downtime and maintenance costs, a hybrid approach that combines traditional methods with data-driven analytics and emerging sensor technologies must be adopted.

1. Introduction

In the past four decades, Industrial Gas Turbines (IGTs) have been employed in power generation, mechanical drives, and marine applications [1, 2]. The performance and reliability of industrial gas turbines are determined by taking measurement of critical parameters such as efficiency, fuel flow, and power output. Traditional methods for testing and evaluating these parameters have followed well-defined procedures and standards [1]. However, the emergence of artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies has necessitated the need to employ these new technologies, in addition to existing traditional methods, to optimize testing methodologies and improve the decision-making process.

The industrial gas turbine performance test procedure provides a structured approach for accurately assessing gas turbine performance while considering the operational environment [1]. Performance testing is essential for newly manufactured, repaired, or overhauled gas turbines [3]. It ensures the optimization of the IGT’s performance and helps minimize unscheduled shutdowns and repairs, as turbine component failures can lead to significant financial losses [1]. Although the testing procedure may involve considerable costs for operators and manufacturers, it serves as a critical foundation for operational decisions, including modifications, performance monitoring, and plant extensions. It also provides valuable complementary data to factory testing results. Established standard testing codes, such as those from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), Verband Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI), and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), have traditionally been used to assess the performance of industrial gas turbines. These codes provide comprehensive guidelines for site preparation, instrumentation requirements, thermodynamic calculations, and test result reporting [4]. They ensure consistency and accuracy across various testing scenarios, facilitating fair comparisons and informed operational decision-making [1].

The efficiency and operational stability of the gas turbine are determined by conducting performance testing. Performance testing provides information about power output, thermal efficiency, and fuel consumption under standardized and varying operational conditions [5]. Affonso et al. [6] stated that obtaining the heat rate is crucial for determining the overall performance of a gas turbine and is most commonly considered when conducting an acceptance test. The guidelines for accurate and repeatable tests, which are provided by international standards such as ASME PTC 22 [4] and ISO 2314 [7], are required to be adhered to when conducting performance testing. Comprehensive methods for evaluating turbine power output and efficiency are provided by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Performance Test Code [4]. Test requirements such as instrumentation setup, environmental correction factors, and test duration are outlined in ISO 2022[8]. A detailed framework for determining performance based on direct measurement and thermodynamic principles is provided in the ASME PTC 22 standard [4].

This review explores the possibility of enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of these tests by critically assessing the traditional methods, their limitations, and how modern technologies, including AI, can be deployed in addition to traditional methods to achieve enhanced testing methodologies and procedures in industrial gas turbines. The focus of this study is on using AI to complement the existing traditional testing approaches, optimize data acquisition, and predict operational failures.

2. Materials and methods

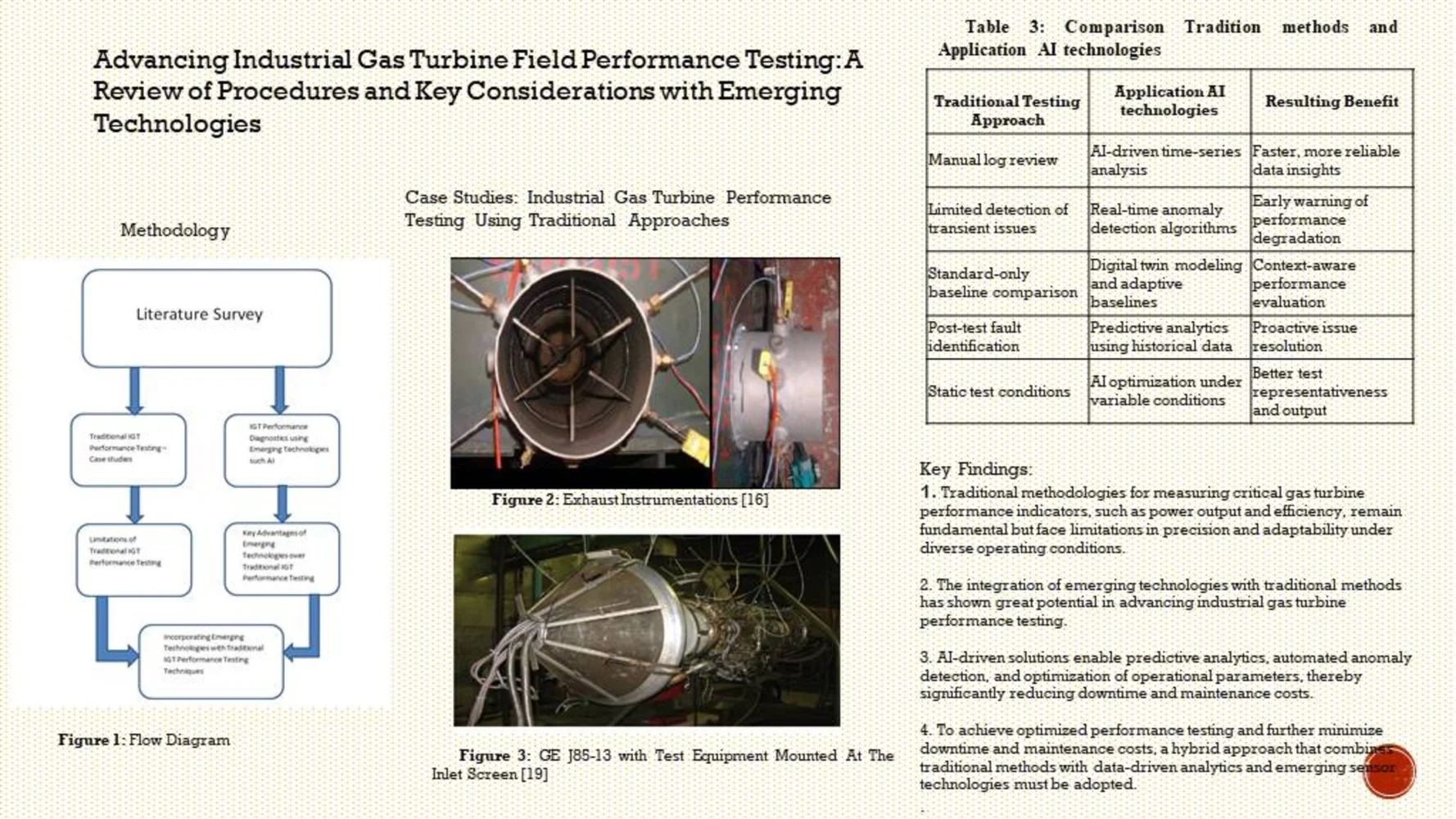

The methodology adopted in this study involved search strategies, inclusion/exclusion criteria, data extraction, and analysis procedures. The strategies adopted in conducting this study include examining current procedures and best practices in industrial gas turbine performance testing, identifying key challenges associated with performance testing, and exploring the role and impact of emerging technologies, including AI, in enhancing gas turbine performance testing. Fig. 1 shows the flow chart of the study.

To identify relevant and important literature in the area of study, a systematic and comprehensive search strategy was employed. Academic and industry databases were pivotal in conducting the study. The academic databases covered in the study include articles from Elsevier, Springer Nature, ASME Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, PhD Thesis from reputable universities etc. The industry databases include the ASME Digital Collection, Gasturbine World, ASME Turbo Expo, and communications from leading gas turbine manufacturers such as General Electric, Siemens, Solar Turbines, and Mitsubishi. Grey literature, including technical reports, industry white papers, and conference proceedings, were also reviewed during the literature search. In addition, key search word combinations such as industrial gas turbine performance testing, gas turbine testing procedures, key considerations in turbine testing were used. Other key word combinations included application emerging technologies in gas turbine performance diagnostics, artificial intelligence in performance testing, and AI-based turbine diagnostics.

The literature was examined through a thematic analysis to uncover recurring patterns and emerging trends. The primary themes identified were as follows: traditional performance testing procedures, including benchmarking methods and their limitations; challenges in performance testing, such as instrumentation errors, environmental variability, and operational constraints; and the integration of emerging technologies, particularly the role of AI and machine learning in optimizing performance.

Fig. 1Flow chart of study

3. Studies on industrial gas turbine performance testing using traditional approaches

Diakunchak [9] conducted a fully factory-loaded test to verify the performance and mechanical integrity of a new engine model. To obtain measurement data on the engine and its components' performance, a large number of specialized instruments were employed. At each measurement point, nearly 500 individual readings were recorded. The results showed that the power output exceeded 47 MW when measurements were conducted under ISO conditions using natural gas as the fuel. Also, the author reported that metal temperature measurements in the combustor and turbine confirmed the engine's mechanical integrity. Bustos et al. [10] stated that during individual test campaign, some major gas turbine components can be verified to ascertain their mechanical integrity and performance. The authors further added that vibration levels in the power turbine are assessed through a mechanical run test (MRT), while the gas generator is expected undergo performance testing to determine whether its operating parameters are within acceptable limits. Lee et al. [11] conducted a performance test on a micro gas turbine consisting of a single-stage centrifugal compressor, a radial turbine, and an annular combustor. Various instrumentations were used to measure temperature, pressure, and flow rate at different sections of the engine as shown in Fig. 2. The compressor inlet and turbine exit temperatures were measured using T-type and K-type thermocouples, respectively, installed within the engine. Meanwhile, the fuel flow rate was measured using a thermal mass flow meter, and the compressor exit pressure was obtained using a pressure probe. Based on the measurement data, the authors calculated the shaft power and thermal efficiency.

Decker and Pathak [12] conducted an Engineer, Procure and Construct (EPC) performance test on Combustion Turbine Generators under base load condition to ascertain the facility-wide unfired net electrical output and heat rate. It was stated that during the test, the Chiller was switch off while the HRSG remained unfired. The study revealed that the corrected unfired net electrical output was greater than the guaranteed value, while the corrected unfired net heat rate was less than the guarantee value. Purvis [13] conducted the measurement of turbine inlet temperature using a single three-point stagnation thermocouple rake at the outlet from each of the six combustion chambers to provide a rough guide to temperature. The authors ensured that single unit readings were never accepted as representing a true mean outlet temperature. Six thermocouple units are usually used to measure the exhaust temperature. Of these, three are installed in the exhaust duct elbows in pairs [30]. Mathioudakis [14] presented methods for correcting data from gas turbine acceptance testing. The study focused on addressing issues that were not sufficiently covered by existing standards. The author presented a procedure for verifying guarantee data at specific operating points, and methods were proposed for correcting performance test data. Kurz et al. [15] discussed field testing of gas turbine-driven compressors and measurement uncertainties when test guidelines were judiciously followed. The authors outlined a compressor field testing procedure that reduces measurement inaccuracies and maintains cost efficiency. In addition, the authors addressed issues related to the planning and organization of field tests and necessary instrumentation. Other areas covered in the study include data reduction, data correction, test uncertainty, and the interpretation of test data. Furthermore, the study reviewed necessary test codes and their relevance to field testing.

Fig. 2Micro gas turbine test facility [11]

![Micro gas turbine test facility [11]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/24894/24894-img2.jpg)

Purvis [13] conducted tests using standard procedures and rules similar to those outlined in the ASME Power Test Code '22 or the CIMAC code of acceptance requirements. The tests were performed on normal production units that were being prepared for delivery or on-site acceptance. During the measurement exercise, attempts were made to provide an alternative for measuring parameters where doubt existed regarding the accuracy of the recorded measurement data. The author used a measuring device that functions by sensing the distortion of the magnetic flux induced by the shaft torque when it was subjected to torsional strain to obtain the measurement of the output torque produced. Performance testing of an APU GTCP was conducted by MSc Thermal Power class of 2010. The performance test was carried out on an APU GTCP 30-92 Avon Test Facility located at Cranfield University, UK, to provide a first-hand insight on the operation of a gas turbine. The APU been investigated was an old gas turbine engine which performs multiple functions in an aircraft (see Fig. 3).

According to Pachidis [16] the measurements were obtained after starting and running until it is stabilized before readings were taken. The fuel flow was measured using a ball flow meter located just before the injection port into the combustion chamber. The flow meter was calibrated for the density of the fuel used, and the corresponding chart between the graduations and fuel flow were used to obtain the fuel flow in kg/s. While the pressure values were measured at the compressor exit and the exhaust using five tubes connected to a digital meter (DP101). The compressor intake total pressure was measured using three of the Pitot probes provided. While the remaining tubes, which consist of a rail of three tubes were used to measure static pressure at the exhaust, whose mean value provides the static exhaust pressure. The compressor delivery temperature and exhaust temperature were measured through thermocouples installed at the exhaust tubes. The K-type thermocouples made of Chromel-Alumel material, which are poor conductors and are well-suited for high-temperature measurements due to their low electromotive force, were used for obtaining the temperature measurements, as shown in Fig. 4. Due to the non-homogeneous gas flow in the exhaust duct, three thermocouple probes were installed at strategic positions according to the British Standard for the measurement of fluid flow.

Fig. 3Main components of the GTCP 30-92 engine [16]

![Main components of the GTCP 30-92 engine [16]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/24894/24894-img3.jpg)

Cong et al. [17] conducted experiments to mimic varying environmental conditions by controlling intake humidity using ultrasonic atomizers. The intake pressure was adjusted with a wind deflector, and intake temperature was regulated by selecting different room temperatures. The measurements collected during the experiment included flow, pressure, temperature, humidity, and smoke composition. Flow and pressure data were obtained using the micro gas turbine’s pre-installed system, while temperature and humidity were measured with an AS847 split-type meter. An infrared smoke analyzer (MGA5) was employed to measure the combustion-generated smoke components. The results showed that operating parameters of the micro gas turbine fluctuated slightly with changes in intake humidity, but the magnitude of these fluctuations was small, indicating that the turbine can operate normally even in high humidity environments. Also, power generation efficiency and compressor power consumption exhibited opposite trends when the intake temperature changed. Changes in intake temperature also affected the concentrations of NOx and CO emissions.

Fig. 4Exhaust instrumentations [16]

![Exhaust instrumentations [16]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/24894/24894-img4.jpg)

Sitanggang et al. [18] conducted an experimental study to analyse the performance of Gas Turbine Units in Jambi, Indonesia. The performance testing was conducted by collecting data accordance ASME Performance Test Code 22. Data obtained included parameters such as inlet air temperature, air filter pressure differential, fuel flow rate, exhaust gas temperature, self-use electrical energy, and electricity production. The kWh-meter transactions in the Generator Auxiliary Control (GAC) room was used to obtain the Net energy production data, while gross energy production data was read from the gross kWh-meter in the Local Control Room. The heat rate and compressor efficiency were calculated from data obtained from the measured parameters.

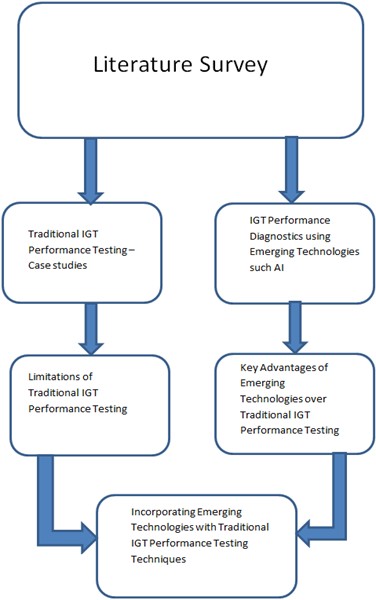

Syverud et al. [19] conducted an investigation to determine the effect of saltwater ingestion on the performance of a General Electric J85-13 turbojet engine. Salt ingestion was achieved by spraying atomized droplets of saltwater into the engine intake, leading to the fouling of salt deposits on the axial compressor. To obtain more detailed data than what was available from the existing test instrumentation, additional sensors were deployed. Figures 5 and 6 show the General Electric J85-13 turbojet engine and test equipment mounted at the inlet screen of the engine respectively. Four sensors positioned at the engine inlet screen measured the compressor inlet temperature. The compressor inlet total pressure was measured using three pitot tubes located in the bellmouth, while the static pressure at the same location was measured using three static ports. Static pressure at stage 5 was recorded via a 1 mm tap located at a single point on the circumference within the bleed channel. Gas path temperatures were measured using unshielded Resistance Temperature Detectors (RTDs) installed at stator rows 1, 3, 4, 6, and 8. Ambient temperature and relative humidity were manually recorded outside the test cell at the same location. The compressor inlet temperature was observed to be higher than the ambient temperature and varied with engine load, attributed to test cell recirculation. A minimum of 60 data points were collected at each setting, using a 2 Hz sampling rate, to reduce data scatter. The average of these readings was taken as the steady-state data point. All performance data were corrected to standard ISO reference conditions (15°C ambient temperature and 101,325 kPa barometric pressures). The authors reported that the largest shift in mean value occurred in the compressor discharge pressure, which resulted in partial overlap of the measurement uncertainties.

Fig. 5Single spool turbojet engine [19]

![Single spool turbojet engine [19]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/24894/24894-img5.jpg)

Fig. 6GE J85-13 with test equipment mounted at the inlet screen [19]

![GE J85-13 with test equipment mounted at the inlet screen [19]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/24894/24894-img6.jpg)

It is evident from the foregoing that numerous studies have been conducted using traditional methods of industrial gas turbine performance testing. Table 1 provides a summary of the key references reviewed for this research, highlighting the key performance parameters measured, the equipment used, and the objectives achieved in the respective tests. From the reviewed literature, it is evident that field performance testing requires considerable human effort for data collection and analysis. Also, accurate calibration of instruments is also required to reduce errors in the measured results. In addition, the personnel conducting the test must have a strong understanding of gas turbine performance calculations to estimate parameters that cannot be measured directly. In light of these challenges associated with traditional performance testing, it has become necessary to integrate emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, to address these issues and optimize the testing process for improved accuracy and efficiency.

3.1. Limitations of traditional gas turbine performance testing

In the recent past, traditional testing procedures have been used to evaluate the performance of gas turbines and provide guidance for maintenance actions. However, these methods face several challenges and limitations, including high costs and time requirements for comprehensive testing, limited flexibility in adapting to new turbine designs, the potential for human errors in data collection and analysis, and the inability to predict long-term performance and degradation trends. These limitations and challenges have necessitated the exploration of more robust and sophisticated methods that use artificial intelligence that can affect their effectiveness [1]. Some of the limitations associated with traditional performance testing are presented below:

1. Manual Data Analysis.

– Time-consuming and prone to human error.

– Limited to steady-state conditions and snapshot data.

2. Delayed Fault Detection.

– Anomalies often detected only after performance deviation becomes significant.

3. Limited Adaptability.

– Performance results do not easily adapt to changing operational environments (e.g., ambient conditions, fuel variability).

4. Reactive Approach.

– Testing focuses on assessing current state rather than predicting future issues or optimization opportunities.

3.2. Integrating emerging technologies in IGT performance testing

Advancements in diagnostic tools have significantly improved the accuracy and efficiency of performance tests [20]. As a result, there is growing interest in leveraging emerging technologies such as AI-based models for predictive analytics, anomaly detection, and performance optimization. Data collection has also been significantly improved through the development of high-precision, wireless, and self-calibrating sensors [21]. Another pivotal technology in performance testing is digital twins, which use virtual replicas to enable real-time simulation and performance analysis of gas turbines [22]. Also, a digital twin models are capable of providing early warning for gas-path faults. The ability to process vast amounts of data and identify patterns that are not readily apparent to human analysts has positioned AI and machine learning as pivotal tools in performance testing.

3.3. Application of emerging technologies for gas turbine performance diagnostics

Industrial gas turbine performance testing can be revolutionized by employing advanced technologies, such as AI, for data acquisition, data analysis, and system behavior prediction. With AI, the process of data acquisition can be automated, and data analysis can be enhanced [23]. Key AI technologies, such as Machine Learning, Deep Learning, Natural Language Processing, and the Internet of Things (IoT), can be employed to achieve automated data acquisition and enhanced data analysis, as mentioned.

Table 1Key references for traditional testing cases studies

Reference | Key parameters measured/ calculated | Equipment employed | Overall target |

Diakunchak [9] | Compressor inlet pressure and temperature, relative humidity, Exhaust temperature and pressure, Power output - Performance Combustor Metal Temperature, fuel flow | K-type thermocouples, digital pressure indicator, Reuter Stokes, Pressure Test Gauge, station meters, Tube Manometer | To verify the performance and mechanical integrity of a new engine model |

Bustos et al. [10] | Vibration levels in the power turbine Performance Test | Mechanical run test (MRT) | To verify mechanical integrity and performance |

Lee et al. [11] | Temperature, pressure, and flow rate at different sections of the engine | T-type and K-type thermocouples-for temperature Thermal mass flow meter for Fuel flow Pressure probe | Performance test on a micro gas turbine |

Decker and Pathak [12] | Net electrical output and heat rate | Permanent plant Instrumentation | Performance test on Combustion Turbine Generators under base load condition to ascertain the facility-wide unfired net electrical output and heat rate |

Purvis [13] | Torque, Exhaust Temperature, Power Output | Thermocouple for temperature Magnetic Flux Torque meter | On-site performance acceptance test |

Pachidis et al. [16] | Fuel flow, Pressure, temperature | K-type thermocouples Ball flow meter Pressure tubes connected to a digital meter | To provide insight on gas turbine engine testing and test data collection and assessment |

Sitanggang et al. [18] | Inlet air temperature, air filter pressure differential, fuel flow rate, exhaust gas temperature, self-use electrical energy, and electricity production | gross kWh-meter | Analyse the performance of Gas Turbine Units in Jambi, Indonesia |

Cong et al. [17] | Flow, pressure, temperature, humidity, and smoke composition | AS847 split-type meter An infrared smoke analyzer (MGA5) | Analyse the performance of micro gas turbines under different intake environmental conditions |

Syverud et al. [19] | Ambient temperature, relative humidity, Compressor Inlet Pressure and temperature, Exhaust temperature and pressure | Pitot tubes, static ports. Static pressure ,1 mm tap, unshielded resistance temperature detectors (RTDs) | To determine the effect of saltwater ingestion on the performance of a General Electric J85-13 turbojet engine |

3.3.1. Machine learning

A tool which is known as machine learning has gain significant recognition for solving physical problems by learning from data [24]. Trained ML models, which typically work without the need of solving physical governing equations, are computationally efficient [25]. Machine learning methods are data-driven approaches that use interconnected sensor systems to transmit real-time measurements from machines to the cloud. These systems create datasets for the models, which analyze large amounts of data to detect patterns and alert users when something is not right [20]. For instance, large volumes of test data can be analyzed using machine learning algorithms to identify patterns and correlations that may be difficult to detect with traditional methods [21]. Shen and Khorasani [26] proposed a data driven fault diagnostic system to monitor engine health status. A hybrid multi-mode machine learning strategies was used to develop the system. The hybrid system comprised the supervised recurrent neural networks and the unsupervised self-organizing maps. The authors reported that the proposed framework and methodology can also be applied for assessing the health status of multiple components by only having access to the input/output sensor data.

A machine learning-based technique was employed to predict gas turbine performance for power generation [27]. Two surrogate models based on High Dimensional Model Representation (HDMR) and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) were developed using real operational data. The authors reported that the operating characteristics of the air compressor and turbine were effectively predicted by the developed models, demonstrating the potential of AI in predicting the performance of gas turbines. Liu et al. [28] developed a physics-informed machine learning methodology that incorporated thermodynamic heat balancing mechanisms, component characteristics, multi-source data, and neural network models to predict gas turbine degradation. The study provided insights into parameters that are difficult to measure directly through the simulation of the thermodynamic performance model under different conditions. The study demonstrated that the complex dynamics of gas turbines can be effectively captured by combining physics-based models with machine learning techniques.

3.3.2. Artificial neural networks

Asgari et al. [29] developed a methodology based on ANN for an offline system identification of a gas turbine. Different ANN models with two-layer feed-forward multi-layer perceptron (MLP) structure were created and trained using a comprehensive computer program code, generated and run on MATLAB environment. The resulting model predicted the performance of the system with high accuracy. The authors reported that a comprehensive view of the performance of different ANN models for system identification of a single shaft GT was achieved using the proposed methodology. Osigwe et al. [30] presented an integrated gas turbine system diagnostic tool, based on ANN diagnostic system, for quantifying gas turbine component and sensor fault. Also, Omoniabipi et al [31]) developed an ANN system to detect deteriorations in transmission cables. Neural networks were employed using MATLAB R2021a and Python, implemented in Visual Studio Code. Data from 132 kV overhead line (OHL) transmission cables, provided by the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN), were utilized in the study. The authors reported that the modeled ANN system successfully identified transmission cable deterioration caused by electric overloading, achieving an accuracy of 77.9 % in recognizing overload patterns.

3.3.3. Digital twin technology

Digital twin technology has emerged as a pivotal tool for monitoring and enhancing gas turbine performance. By creating virtual replicas of physical turbines, digital twins enable real-time data analysis, facilitating predictive maintenance and performance optimization [32-34]. This technology collects and processes real-time data from numerous sensors embedded in gas turbines, providing valuable insights that enhance operational efficiency and reliability. Through digital twin solutions, organizations can proactively identify issues, reduce downtime, and optimize turbine performance. Panov and Cruz-Manzo [32] opined that gas turbine performance can be virtually simulated under various conditions using digital twins, which have the capacity to provide insights for optimization. Zhang et al. [35] proposed a digital twin approach to fuse physical mechanisms and big data by integrating machine learning, performance adaptation and component matching methods. Panov and Cruz-Manzo [32] conducted an investigation on a field trial of the Performance of a Digital Twin system deployed onto a PC-based platform at an operational site. Field data collected covering several months were analysed to assess performance of the deployed Digital Twin. The Digital Twin utilized various gas turbine sensors to detect variations in predicted engine health conditions, which served as indicators of common gas path faults and degradation patterns. The authors highlighted that the Digital Twin system successfully fulfilled its intended functions, particularly in tracking gas turbine performance and performing diagnostics.

3.3.4. Other technologies

Deep Learning models are particularly suited for handling complex, non-linear relationships in test data. These models are especially effective for visual inspections and monitoring turbine performance over time due to their superior image recognition and time-series analysis capabilities. A deep learning approach was explored by Yan and Yu [36] to detect anomalies in gas turbine combustors. The authors stated that the deep learning approach, which involved hierarchically learning features from exhaust gas temperature sensor measurements, demonstrated improved combustor performance anomaly detection, highlighting the efficacy of deep learning in diagnostics. Also, Natural Language Processing (NLP) can be used to extract valuable insights that provide necessary information for test planning and execution by analysing test reports and maintenance logs. The Internet of Things, on the other hand, enables real-time monitoring of IGT parameters through a network of interconnected sensors, facilitating continuous data acquisition; thereby reducing the need for periodic testing. In recent years, the integration of the Internet of Things (IoT) into gas turbines for monitoring engine performance has gained significant attention [20]. IoT technologies are playing a pivotal role in achieving enhanced efficiency and reliability in gas turbine operations by enabling real-time data acquisition, advanced analytics, and predictive maintenance.

Togni et al. [37] proposed a performance-based diagnostic system for detecting single and multiple failures in a two-spool engine, utilizing a combination of methodologies. To enhance the system’s success rate, Kalman Filter (KF), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and Fuzzy Logic (FL) techniques were integrated. The system targeted specific failure types, including compressor fouling, turbine fouling, and turbine erosion. In random simulations involving varying deterioration magnitudes and failure types, the system achieved success rates exceeding 92.0 % for quantification and 95.1 % for classification.

Ma et al. [21] presented a novel approach for anomaly detection in gas turbines using a digital twin framework. The developed system consisted of an Uncertain Performance Digital Twin (UPDT) and a fault detection component. The UPDT modeled the expected performance behavior of real-world gas turbine engines operating under varying conditions. The fault detection module was designed to identify UPDT outputs that exhibit low probability under the training distribution. To train and test the UPDT model, a real full-flight operation data of a turbofan engine was used. Seven parameters namely static air temperature, altitude, Mach number, low pressure rotor speed, Thrust Lever Angle resolver, Selected VSV Position, Selected VBV position, which are used to characterize the engine operating conditions and thrust setting were used as input data, while Exhaust gas temperature, fuel flow and high pressure rotor speed were considered as the target outputs. The study demonstrated that the proposed method effectively detects abnormal samples, thereby improving fault detection once anomalies are identified. Table 2 presents key references reviewed for the application emerging technologies including AI for gas turbine performance diagnostics.

Table 2Case studies involving technologies deployed for gas turbine performance diagnostics

Reference | Type of AI technologies employed | Overall target |

Liu et al. [28] | Physics-informed machine learning methodology | To predict gas turbine degradation |

Liu, Z. and Karimi [24] | Machine learning-based technique | To predict gas turbine performance |

Yan and Yu [36] | A deep learning approach | To detect anomalies in gas turbine combustors |

Omoniabipi et al. [31] | Artificial Neural Networks | To detect deteriorations in transmission cables |

Panov and Cruz-Manzo [32] | Digital Twin system | To detect variations in predicted engine health conditions |

Togni et al. [37] | Combination of methodologies: Kalman Filter (KF), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and Fuzzy Logic (FL) techniques | For detecting single and multiple failures in a two-spool engine |

Ma et al. [21] | Digital Twin framework | For anomaly detection in gas turbines |

Shen and Khorasani [26] | Hybrid multi-mode machine learning strategies | to monitor engine health status |

4. Findings

From the literature review conducted on industrial gas turbine performance testing, including the assessment of various test procedures, key considerations, and the transformative role of emerging technologies, a detailed combination of findings is presented. Traditional testing methods outline standard procedures for evaluating the performance of gas turbines. These methods include steady-state, transient, and emission testing. Steady-state testing involves measuring parameters such as temperature, pressure, and fuel flow under stable operating conditions, while transient testing entails monitoring dynamic responses to load changes or operational events. For emission testing, the exhaust gas composition is examined to ensure compliance with environmental regulations.

The study revealed that it is essential to monitor key parameters such as, efficiency, power output, exhaust temperature and gas flow rate, air temperature, pressure ratios, and airflow rates, to assess the performance of gas turbines. These parameters provide valuable insights into the turbine’s condition, enabling operators to identify issues related to efficiency degradation. With this information, operators can take appropriate measures to optimize the turbine’s performance. To optimize the operation and performance of IGTs, it is imperative to ensure that the efficiency, fuel flow, power output, capacity, and all control installations are adequately verified.

The study revealed that traditional methods provided a reliable foundation for performance testing. However, they are associated with numerous challenges, including being labor-intensive and prone to inaccuracies due to sensor limitations and variations in environmental conditions. These limitations highlight the need for integrating advanced technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, for a more automated and adaptive testing solutions to improve accuracy and efficiency.

It is evident from the reviewed studies that measured data were essential wherever emerging technologies were applied to assess gas turbine performance. Standard performance test data, obtained through established ASME or ISO procedures, provided key parameters such as turbine inlet temperature (TIT), compressor pressure ratio, exhaust temperature, fuel flow, shaft speed, and vibration. These parameters form the foundation upon which artificial intelligence (AI) methods rely to optimize performance testing. Data generated through traditional testing approaches also serves as training input for machine learning models. The studies indicate that emerging technologies like AI build upon these traditional methods-especially in data-rich, repeatable processes such as instrumentation, logging, and normalization. These features form the basis for AI technologies to make the entire testing cycle faster, smarter, and more adaptive.

The study further revealed that gas turbine performance testing can be significantly optimized by integrating artificial intelligence (AI) techniques such as machine learning, digital twins, deep learning, and artificial neural networks into traditional testing methods. AI enhances efficiency by enabling better planning, reducing unnecessary tests, and minimizing delays caused by weather or load conditions. This is possible because machine learning models, trained on historical operational data, can recommend optimal testing conditions and accurately detect faulty readings, data noise, and instrument drift. Also, AI can simulate ideal turbine behavior for comparison with actual test data, allowing for more precise evaluation. It can also track test results over time to identify trends that may indicate issues such as compressor fouling, turbine blade degradation, or seal leakage.

While the review provides valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. The rapid development of AI and sensor technologies may render some findings out-dated. In addition, limited access to proprietary industry data constrained the analysis, and the focus on peer-reviewed literature may have excluded relevant grey literature.

Key findings from the study which highlight the significance of the integration emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence into traditional gas turbine performance testing methodologies are presented in Table 3.

Table 3Comparison tradition methods only and application AI technologies

Traditional testing approach | Application AI technologies | Resulting benefit |

Manual log review | AI-driven time-series analysis | Faster, more reliable data insights |

Limited detection of transient issues | Real-time anomaly detection algorithms | Early warning of performance degradation |

Standard-only baseline comparison | Digital twin modeling and adaptive baselines | Context-aware performance evaluation |

Post-test fault identification | Predictive analytics using historical data | Proactive issue resolution |

Static test conditions | AI optimization under variable conditions | Better test representativeness and output |

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive review of established procedures, key considerations, and emerging trends in gas turbine performance assessment to improve testing practices. Traditional methodologies for measuring critical performance indicators, such as power output and efficiency, remain fundamental but face limitations in precision and adaptability under diverse operating conditions.

Key considerations, including accurate instrumentation, standardized testing protocols, and comprehensive data collection, are essential for reliable assessments. The integration of emerging technologies with traditional methods has shown great potential in advancing industrial gas turbine performance testing.

AI-driven solutions enable predictive analytics, automated anomaly detection, and optimization of operational parameters, thereby significantly reducing downtime and maintenance costs. Additionally, machine learning models enhance data processing, providing deeper insights into turbine performance trends.

To achieve optimized performance testing and further minimize downtime and maintenance costs, a hybrid approach that combines traditional methods with data-driven analytics and emerging sensor technologies must be adopted.

References

-

M. P. Boyce, Gas Turbine Engineering Handbook (3rd ed.). Boston: Elsevier, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-7506-7846-9.x5000-7

-

S. Ahsan, T. A. Lemma, M. B. Hashmi, and X. Liang, “Investigation of operational settings, environmental conditions, and faults on the gas turbine performance,” Measurement Science and Technology, Vol. 35, No. 12, p. 125902, Dec. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ad678c

-

https://themethodstatement.com/testing-and-commissioning-of-gas-turbine/#google_vignette

-

Asme, “Gas Turbines, ASME PTC 22 2005,” America Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York, 2005.

-

https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/42989/9610d6b713be422a91d59d6da8cecd74/ISO-2314-2009.pdf, (accessed 1 March 2025).

-

L. O. A. Affonso and S. D. J. Oliveira, “Field Performance Testing Of Turbomachinery,” in Proceedings of COBEM 2005, 18th International Congress of Mechanical Engineering, Nov. 2005.

-

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, “PTC 4 – Fired Steam Generators,” America Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York, 2005.

-

M. Ohta and K. Handa, “ISO-2022-JP-2: Multilingual Extension of ISO-2022-JP,” RFC Editor, Dec. 1993, https://doi.org/10.17487/rfc1554

-

I. S. Diakunchak, “Operating Experience and Site Performance Testing of the CW251B12 Gas Turbine Engine,” in ASME 1992 International Gas Turbine and Aeroengine Congress and Exposition, Jun. 1992, https://doi.org/10.1115/92-gt-236

-

E. Bustos, M. Hotho, M. Mossolly, and A. Mastropasqua, “Gas turbines and associated auxiliary systems in oil and gas applications,” in Turbomachinery Pump and Symposia, 2017.

-

J. J. Lee, J. E. Yoon, T. S. Kim, and J. L. Sohn, “Performance Test and Component Characteristics Evaluation of a Micro Gas Turbines,” Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 141–152, 2007.

-

A. Decker and P. Parag Pathak, “73.09.02.010_FR_EPC – EPC Final Performance Test Report. Grand River Energy Center Unit 3 KED Project No. 2014-071,” Oct. 2017.

-

https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/bd2631ca-75d0-4371-b77a-78336d129f4b/content, (accessed 20 February 2025).

-

K. Mathioudakis, “Gas Turbine Test Parameters Corrections Including Operation With Water Injection,” Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, Vol. 126, No. 2, pp. 334–341, Apr. 2004, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1691443

-

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/87265368.pdf, (accessed 15 January 2025).

-

V. Pachidis, “APU GTCP30-92 Laboratory Experiment Guide,” Cranfield University, Thermal Power M.Sc. Course, Dec. 2008.

-

L. Cong, S. Zhijun, L. Yimin, Z. Zhongning, and M. Lina, “Experimental study on the performance of micro gas turbines under different intake environments,” Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, Vol. 58, p. 104415, Jun. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2024.104415

-

R. B. Sitanggang, P. Paryanto, and B. W. Hadi Eko Prasetiyono, “Analyzing Gas Turbine Performance Through Simulation and Performance Tests: Case Study of Gas Turbine Units in Jambi, Indonesia,” TEM Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 2370–2377, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.18421/tem124-49

-

E. Syverud, “Axial compressor performance deterioration and recovery through online washing,” PhD thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway, 2007.

-

M. D. C. Rubiales Mena, A. Muñoz, M. Sanz-Bobi, D. Gonzalez-Calvo, and T. Álvarez-Tejedor, “Application of ensemble machine learning techniques to the diagnosis of the combustion in a gas turbine,” Applied Thermal Engineering, Vol. 249, p. 123447, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123447

-

Y. Ma, X. Zhu, J. Lu, P. Yang, and J. Sun, “Construction of Data-Driven Performance Digital Twin for a Real-World Gas Turbine Anomaly Detection Considering Uncertainty,” Sensors, Vol. 23, No. 15, p. 6660, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23156660

-

E. Kandemir, A. Hasan, T. Kvamsdal, and S. Abdel-Afou Alaliyat, “Predictive digital twin for wind energy systems: a literature review,” Energy Informatics, Vol. 7, No. 1, Aug. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1186/s42162-024-00373-9

-

Z. Zou, P. Xu, Y. Chen, L. Yao, and C. Fu, “Application of artificial intelligence in turbomachinery aerodynamics: progresses and challenges,” Artificial Intelligence Review, Vol. 57, No. 8, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-024-10867-3

-

R. M. Neal, Technometrics. Informa UK Limited, 2007, pp. 366–366, https://doi.org/10.1198/tech.2007.s518

-

J. Li, X. Du, and J. R. R. A. Martins, “Machine learning in aerodynamic shape optimization,” Progress in Aerospace Sciences, Vol. 134, p. 100849, Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paerosci.2022.100849

-

Y. Shen and K. Khorasani, “Hybrid multi-mode machine learning-based fault diagnosis strategies with application to aircraft gas turbine engines,” Neural Networks, Vol. 130, pp. 126–142, Oct. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2020.07.001

-

Z. Liu and I. A. Karimi, “Gas turbine performance prediction via machine learning,” Energy, Vol. 192, p. 116627, Feb. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2019.116627

-

X. Liu et al., “Intelligent fault diagnosis methods toward gas turbine: A review,” Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 93–120, Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2023.09.024

-

H. Asgari, X. Chen, M. B. Menhaj, and R. Sainudiin, “Artificial Neural Network-Based System Identification for a Single-Shaft Gas Turbine,” Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, Vol. 135, No. 9, pp. 092601–7, Sep. 2013, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4024735

-

O. E. Osigwe, Y. Li, S. Suresh, and G. Jumbo, “Integrated Gas Turbine System Diagostics: Components and Sensor Faults Quantification Using Artifical Neural Network,” 2017.

-

C. S. Omoniabipi, R. Agbadede, K. C. Emmanuel, O. J. Adewuni, and I. Allison, “Investigation of the application of an automated monitoring system for detecting transmission cable deterioration in Nigeria: A case study of transmission cable lines between Offa and Oshogbo,” Results in Engineering, Vol. 25, p. 104165, Mar. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104165

-

V. Panov and S. Cruz-Manzo, “Gas Turbine Performance Digital Twin for Real-Time Embedded Systems,” in ASME Turbo Expo 2020: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Sep. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1115/gt2020-14664

-

V. M. Kaplan, “Digital Twin Model for Gas Turbine Power Generation Forecasting,” Master’s thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway, 2023.

-

A. Rasheed, O. San, and T. Kvamsdal, “Digital Twin: Values, Challenges and Enablers from a Modeling Perspective,” IEEE Access, Vol. 8, pp. 21980–22012, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2020.2970143

-

J. Zhang, Z. Wang, S. Li, and P. Wei, “A digital twin approach for gas turbine performance based on deep multi-model fusion,” Applied Thermal Engineering, Vol. 246, p. 122954, Jun. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.122954

-

W. Yan and L. Yu, “On Accurate and Reliable Anomaly Detection for Gas Turbine Combustors: A Deep Learning Approach,” in Annual Conference of the PHM Society, Vol. 7, No. 1, Oct. 2015, https://doi.org/10.36001/phmconf.2015.v7i1.2655

-

S. Togni, T. Nikolaidis, and S. Sampath, “A combined technique of Kalman filter, artificial neural network and fuzzy logic for gas turbines and signal fault isolation,” Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 124–135, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2020.04.015

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The authors are exceedingly grateful to Faculty of Engineering, Nigeria Maritime University, Okerenkoko, for providing all technical assistance.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Roupa Agbadede: conceptualization, data curation, supervision, project administration, writing some parts of the original, and review and editing. Biweri Kainga: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing some sections of the original draft.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.