Abstract

The deformation behavior of automotive double-cell thin-walled tubes under oblique loading is inherently complex. To address this crashworthiness design challenge, this study employs a decision-tree-based data-mining method to guide the structural design of thin-walled tubes. In contrast to conventional black-box optimization approaches, the proposed approach not only accomplishes structural optimization but, more importantly, derives design rules for the tubes, enabling critical parameter identification and design domain reduction. By analyzing the crashworthiness responses of double-cell tubes under oblique loading, the method establishes an interpretable linkage between design variables and crashworthiness performance, thereby providing engineers with design guidance. The results show that the optimization design efficiency based on data mining improved by nearly 10 times relative to traditional methods, highlighting its potential to significantly reduce design time and development cost.

Highlights

- A decision-tree-based data-mining approach is proposed for crashworthiness design of double-cell thin-walled tubes under oblique loading.

- The proposed method overcomes the limitations of black-box optimization by identifying critical design parameters and deriving interpretable design rules.

- The data-mining-based optimization improves design efficiency by nearly one order of magnitude, significantly reducing design time and development cost.

1. Introduction

Thin-walled tubes are widely used in the design of energy-absorbing structures for vehicles and trains to ensure structural crashworthiness [1]. During collisions, thin-walled tubes undergo plastic deformation, effectively converting kinetic energy into internal energy, thereby demonstrating excellent energy absorption characteristics. Among various configurations, multi-cell thin-walled tubes have been widely studied due to their great performance in energy absorption. Studies have shown that, compared with square tubes [2] and even foam-filled tubes [3], multi-cell tubes have better energy absorption performance. Under axial loading conditions, multi-cell structures can absorb more impact energy than traditional thin-walled structures of the same mass.

Although thin-walled tubes exhibit excellent energy absorption capabilities under axial crushing, in actual vehicle frontal collision scenarios [4], the thin-walled structures longitudinally arranged at the front of the vehicle are usually subject to different degrees of oblique load [5, 6], as illustrated in Fig. 1. Researches have shown that the deformation mode and energy absorption efficiency of thin-walled tubes are significantly affected by changes in the oblique loading angle. Particularly, when tubes are subjected to oblique load and the loading angle exceeds the critical value, the progressive crush mode of tubes will transform into the global bending collapse mode, resulting in a sharp decline in energy absorption [7, 8]. Therefore, the impact of oblique loads on the crashworthiness of thin-walled tubes should not be overlooked during the design process.

To address the challenges posed by oblique loads, researchers have employed experiments, numerical simulations, and theoretical models to investigate the deformation mechanisms and energy absorption performance of thin-walled tubes. Experimental and simulation studies provide insights into deformation modes and the effects of key parameters [5, 8, 10, 11]. Meanwhile, researchers have proposed theoretical models by modifying existing axial or bending deformation formulas to establish predictive equations that explain the complex coupled deformation of thin-walled beams under oblique loads [6, 12, 13]. However, the geometric complexity of multi-cell thin-walled tubes increases the difficulty of these theoretical derivations, thereby reducing their predictive accuracy.

Fig. 1Schematic of oblique loads in the actual collision conditions [9]

![Schematic of oblique loads in the actual collision conditions [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img1.jpg)

In performance-driven parameter design of thin-walled tubes, traditional optimization algorithms [14-16] typically treat the structural design as a black-box problem [17], generating optimal solutions through automatic search processes. Fang et al. [18] successfully achieved optimal design of multi-cell tubes under oblique loads by combining Kriging models and multi-objective particle swarm optimization. Liu et al. [19] established a surrogate model of the crashworthiness indices with respect to the design variables by SVM. And multi-objective optimization of square carbon fiber reinforced plastic tubes for crashworthiness has been realized in their study. However, due to the uncertainty of these methods, the final designs often fall into infeasible parameter spaces. Moreover, traditional optimization approaches can’t reveal the interactions between design variables and responses, making it difficult to derive useful design rules that could assist engineers in developing similar structures.

To overcome the limitations of traditional methods, this study employs a data mining method based on decision trees, using the multi-angle crashworthiness design of double-cell thin-walled tubes as a case study. Through data mining, the study reveals the implicit relationships between thin-walled tube design variables and crashworthiness performance, and explicitly presents these correlations. In the way, key design parameters influencing crashworthiness and the range of the values of these key parameters can be determined quantitatively. Furthermore, this study compares the optimal design of double-cell thin-walled tubes based on the reduced design domain obtained through data mining with the original design domain. By comparing the two methods, the effectiveness of the data mining method in improving design efficiency is validated.

2. Research problem

In frontal crash situations, the thin-walled structures arranged longitudinally at the front of the vehicle (such as the front longitudinal beams) are often subjected to loads from different angles. Variations in the direction of these loads introduce significant uncertainty into the deformation modes, often leading to coupling between compression and bending or overall structural instability. This unpredictability reduces the energy absorption efficiency of thin-walled tubes and increases the risk of occupant injury [20].

This deformation instability is illustrated in Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Table 1, which compare the deformation modes of aluminum double-cell thin-walled tubes under different oblique loading angles [9]. It can be observed that when the oblique load angle is small, the thin-walled tube exhibits an axial progressive compression deformation mode. At this point, the collision force rapidly rises, then slightly drops, and subsequently fluctuates around a certain lateral value, indicating that the thin-walled tube has good energy absorption performance. As the oblique angle increases, the deformation mode shifts progressively toward global bending, with the collision force rising to a peak before rapidly decreasing. The energy absorption performance of the thin-walled beam decreases. Table 1 further shows that when the oblique loading angle increases from 10° to 20°, the energy absorption of the double-cell thin-walled tube decreases by 77.76 %, and the initial peak force decreases by 18.15 %, quantitatively demonstrating that the energy absorption capacity of the structure declines with increasing oblique loading angle. This structural deformation instability complicates the study of the collision resistance performance of thin-walled tubes under oblique load.

Fig. 2Deformation mode of FE model of double-cell thin-walled tube under oblique angles [9]

![Deformation mode of FE model of double-cell thin-walled tube under oblique angles [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img2.jpg)

a) 0°

![Deformation mode of FE model of double-cell thin-walled tube under oblique angles [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img3.jpg)

b) 10°

![Deformation mode of FE model of double-cell thin-walled tube under oblique angles [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img4.jpg)

c) 20°

Fig. 3Force-displacement curves of the numerical model of double-cell thin-walled tube under different loading angles [9]

![Force-displacement curves of the numerical model of double-cell thin-walled tube under different loading angles [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img5.jpg)

a)0°

![Force-displacement curves of the numerical model of double-cell thin-walled tube under different loading angles [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img6.jpg)

b)10°

![Force-displacement curves of the numerical model of double-cell thin-walled tube under different loading angles [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img7.jpg)

c)20°

Table 1Energy absorbed and initial peak force by double-cell thin-walled tube under different load angles [9]

Energy absorbed / kJ | Initial peak force / kN | |

0° | 7.25 | 90.38 |

10° | 7.24 | 54.22 |

20° | 1.61 | 44.38 |

Researches have shown that exhibit better impact resistance than single-cell thin-walled tubes. However, they also demonstrate greater deformation instability under oblique loading [9]. As illustrated in Fig. 4, with an increasing number of unit cells, the global bending mode emerges at smaller oblique load angles, indicating that the deformation stability of multi-cell thin-walled beams decreases with an increase in the number of unit cells. This increase in deformation instability further complicates the study of multi-angle collision resistance performance for multi-cell thin-walled tubes.

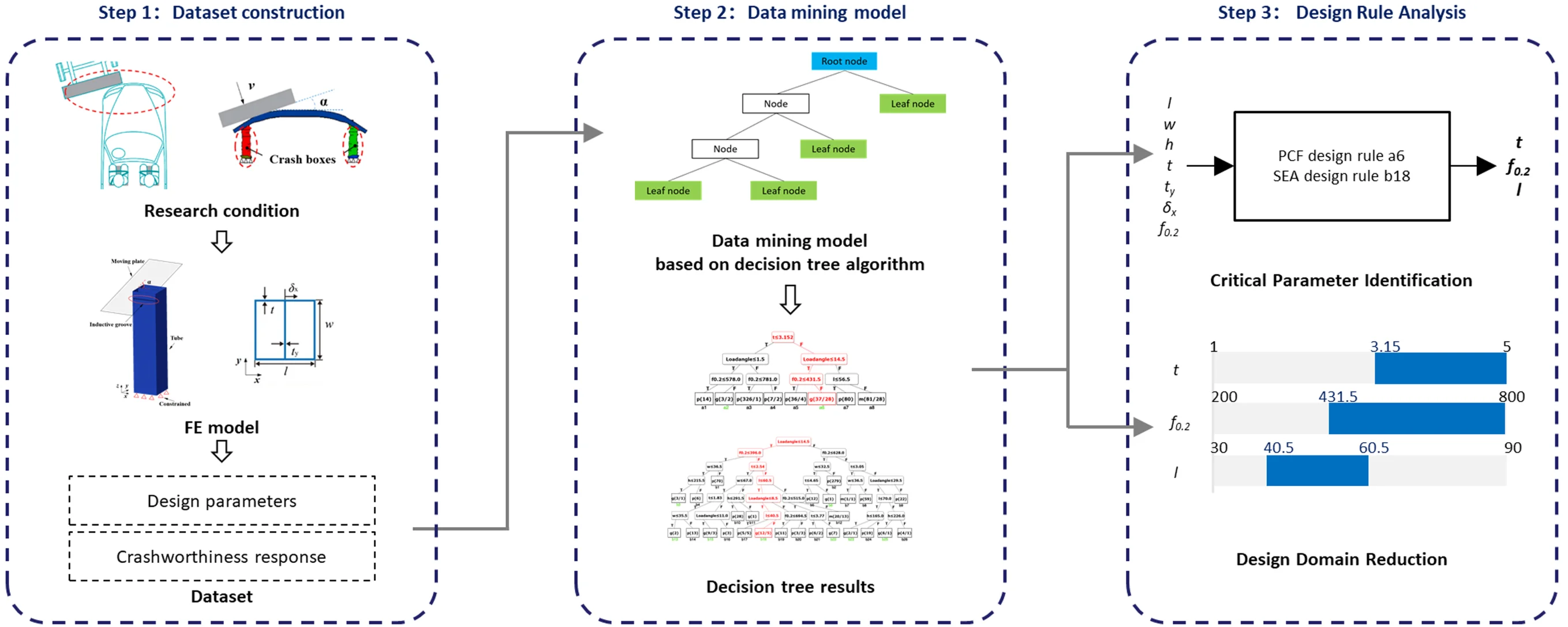

3. Method

This study uses a data mining method based on decision trees. Through the decision tree algorithm, data mining is performed on the dataset of research object to obtain the implicit relationship between the design parameters of the study object and the target response and display this relationship, identifying the key parameters in the dataset that affect the response of the study object. Meanwhile, the design range of the key parameters is quantitatively determined according to the design objectives, thereby reducing the design domain of the study object. The general process of this method is shown in the figure. The general workflow of the proposed method is illustrated in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4Comparison of deformation modes with four multi-cell tubes under different load angles [9]

![Comparison of deformation modes with four multi-cell tubes under different load angles [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img8.jpg)

Fig. 5Research framework

3.1. Dataset construction and preprocessing

Before initiating the study, it is necessary to analyze the research subjects, establish corresponding datasets, and perform data preprocessing suitable for decision tree-based data mining. Specifically, first establish an accurate finite element model to simulate the research conditions. Analyze the design problem, determine the design variables and their ranges of variation. Then, apply the experimental design (DOE) method based on the Hammersley sampling criterion in the design space to construct a test matrix, generate design samples that uniformly cover the design space, and create the corresponding finite element models in batch. During the sampling process, the th -dimensional Hammersley sampling point is calculated by the following equation [21]:

where is the total number of samples, is the index of the sample (a non-negative integer), and is a prime number, often selected from values such as 2, 3, 5, 7, etc., to improve the uniformity of the sequence. The function is the inverse basis function of the Hammersley sequence, which transforms the index into an evenly distributed point in the parameter space.

Before the data mining model training, the joint probability distribution of input features should be determined. Due to the randomness of uncertainty in engineering design and manufacturing, we use the Gaussian distribution as the default PDF if there is no prior knowledge of the interval distribution (e.g. ), where is defined as the mean [22]. The 3-sigma rule, which covers most parts of a Gaussian distribution, is adopted over the whole interval range with the PDF defined as:

where is the normal distribution, and 1/0.997 is a normalization factor to adjust the probability within an interval to 1.

In addition, the crashworthiness responses of each design sample are obtained from finite element simulations and subsequently preprocessed through a grading classification using the following equation:

where is the response, is the number of response, is the number of categories, is the lower limit of the class and is the upper limit. To adapt to the subsequent decision tree algorithm, category labels are assigned to the responses of each sample according to actual engineering requirements.

3.2. Data mining model

In this study, a data mining model based on the decision tree algorithm is developed to analyze the dataset of research subject to achieve critical parameter identification and design domain reduction. The decision tree algorithm is one of the most widely used algorithms in data mining and is highly effective in addressing classification problems. The algorithm exhibits strong interpretability. By learning from a design dataset generated from simulations, this method uncovers the implicit interrelations between the design variables and the responses and presents these relationships explicitly, which helps designers better understand the design problem and make informed design decisions when developing similar products.

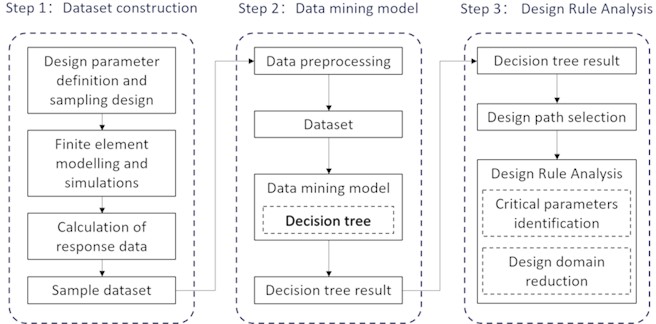

Structurally, a decision tree consists of a root node, internal nodes corresponding to feature-based decision points, and leaf nodes representing classification outcomes, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Each path from the root to a leaf encodes a specific classification rule.

The specific steps for classification using the decision tree algorithm are as follows. Identify the optimal feature from the samples in the dataset as the root node for classification. Then, evaluate the features and classifications in the data based on the classification criteria of the root node. If the attributes of the data to be classified are the same as those of other nodes, they are considered to belong to the same type; if different, they can be regarded as a new node [23]. This process is recursively repeated until the entire tree is constructed.

There are various types of decision tree algorithms. To account for the uncertainty in engineering design, this study employs the decision tree algorithm for uncertain data (DTUD) proposed by Du et al. [22] to construct the data mining model. The DTUD shares a similar structure with conventional decision trees. Its key distinction lies in incorporating a probabilistic mechanism into the node-splitting process. In this framework, each sample is no longer treated as a deterministic point but as an uncertain region within the feature space, typically represented as an interval and assumed to follow a specific probability density function.

Fig. 6A typical decision tree architecture

In this study, information gain, gain ratio, and Gini index are adopted as candidate criteria for node splitting during DTUD training.

Information gain is derived from information entropy and quantifies the increase in dataset purity before and after splitting. The corresponding calculation formula is given as follows [24]:

where is the dataset, is entropy of the target variable, is the number of branches, and is a part of the primary data whose characteristic value is . Also means the size of .

Gain ratio corrects the bias of information gain toward multi-valued attributes by introducing the intrinsic value (IV) of the attribute. The corresponding formula is given as follows:

Gini index quantifies the probability that a randomly selected sample from the dataset would be incorrectly classified. Gini index for a data subset 𝐷 is defined as follows:

where denotes the probability that a sample belongs to class . For an attribute , the corresponding Gini index is computed as follows:

3.3. Design rule analysis

The results of the decision tree usually contain multiple branches. To obtain the design path corresponding to the “target level,” it is necessary to select from the branches where the leaf nodes are at the “target level.” If there are multiple branches with leaf nodes at the “target level,” the decision path with a higher probability of classification as the “target level” and containing more data should be selected as the design rule, which implies better robustness [16].

By analyzing the selected design rule, key parameter identification (CPI) and design domain reduction (DDR) are effectively achieved. In accordance with the decision tree algorithm, the feature attribute that maximizes the splitting criterion at each partitioning stage is selected to obtain the highest gain in classification purity. As a result, the attributes appearing along a design path are recognized as having the strongest influence on the classification of the target responses. These attributes are defined as key design variables, and their relative importance decreases progressively from the upper to the lower nodes of the path.

Each design rule also conveys explicit information regarding the variable ranges, indicating that within these ranges, the probability of the final design achieving the target performance level is greater. These ranges are employed as the reduced design domain, within which the subsequent optimization of the key variables is conducted. Conversely, variables absent from the design paths exhibit limited influence on response classification and can be fixed according to engineering experience and practical design requirements, thereby reducing unnecessary tuning of non-critical variables.

For design rules of multiple responses, a comprehensive synthesis of the design rules extracted for different responses is conducted. Variables that appear in design rules are identified as key parameters influencing multiple responses simultaneously. The intersection of their respective design domains defines the reduced design domain, which satisfies multiple response objectives and provides a focused and efficient foundation for subsequent design.

4. Case study: multi-angle crashworthiness design of double-cell thin-walled tubes

In this study, the crashworthiness of double-cell thin-walled tubes under oblique loading is investigated as a design case to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed data mining approach. The extracted design rule is subsequently applied to the optimization design, and the results are compared with those obtained from the original design domain, thereby verifying the effectiveness of this data mining method in improving design efficiency.

4.1. Data preparation for crashworthiness analysis of double-cell thin-walled tubes

To investigate the crashworthiness of double-cell thin-walled tubes under oblique loading, a finite element (FE) model, as illustrated in Fig. 7(a), was developed to construct a multi-angle crashworthiness dataset for subsequent data mining analysis.

The cross-section of the double-cell tube is shown in Fig. 7(b). The total structure height of the multi-cell tube is . The total length and width of the cross-section are and . The thickness of the rectangular wall outside the cross-section is . are the thicknesses of the intermediate ribs parallel to the -axis, respectively. represents the offset ratio of the intermediate ribs parallel to the -axis relative to the central axis of the cross-section, respectively. Referring to previous studies, the general geometric parameter design ranges for automotive double-cell tubes are listed in Table 2. The value range of and is set to 30-90 mm, the value range of and is set to 1.0-5.0 mm, the value range of is –0.3-0.3, and the value range of is set to 150-300 mm. The value range of is 0-40° to ensure covering enough oblique loads.

The material properties of aluminum alloy AA6063-T5 can be well fitted to the actual material curve using the parametric curve calculated by the following equation [21]:

where is the elastic modulus, is the residual strain which generally set as 0.002, is the stress corresponding to the residual strain which generally the equivalent yield stress corresponding to the residual strain and is the strain hardening index. Referring to previous research [9], this study only selected as the material parameter variable, with a range set from 200 to 800 MPa, as shown in Table 2. and were set as fixed values ( 71 GPa and 30).

To ensure that the design parameters are uniformly sampled across their entire range of values, an experimental design (DOE) method based on Hammersley sampling criteria was used to establish a test matrix. A total of 800 design cases are generated, and corresponding finite element models are developed to simulate their crash responses. The simulation results form a complete dataset for further data mining.

Fig. 7a) FE model of double-cell tubes; b) structures description of double-cell tubes [9]

![a) FE model of double-cell tubes; b) structures description of double-cell tubes [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img11.jpg)

a)

![a) FE model of double-cell tubes; b) structures description of double-cell tubes [9]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25270/25270-img12.jpg)

b)

4.2. Data preprocessing for crashworthiness analysis of double-cell thin-walled tubes

As an energy-absorbing structure, thin-walled tubes should absorb as much energy as possible per unit mass. Therefore, the specific energy absorption (SEA) is selected as a target response and is maximized in crashworthiness optimization. Meanwhile, the peak crushing force (PCF) reflects the severity of the collision, which is highly correlated with occupant injury. Therefore, PCF is selected as another target response and minimized in the optimization problem [25].

SEA is the ratio of the amount of energy absorbed to the mass of tube during the crushing process. SEA can be calculated as follows [26]:

where is the instantaneous crushing force, is the crush displacement, is the mass of the tube.

PCF is the maximum crush force measured during the crushing process of the tube, as expressed as follows [27]:

Before using decision trees for data mining on a dataset, it is necessary to classify and label the target responses based on safety regulations or the experience of designers. In this study, considering the design objectives of maximizing SEA and minimizing PCF, and with reference to the crashworthiness responses of the initial design (SEA = 163.56 kJ, PCF = 500.09 kN), the classifications are as follows: for SEA, values in the range SEA > 150 J/kg are labeled as “good”; 100 < SEA ≤ 150 J/kg as “intermediate”; and 0 < SEA ≤ 100 J/kg as “poor.” For PCF, values in the range 0 < PCF ≤ 500 N are labeled as “good”; 500 < PCF ≤ 600 N as “intermediate”; and PCF > 600 N as “poor.”

4.3. Data mining model for double-cell thin-walled tubes

In this study, data mining models based on the DTUD algorithm were developed to achieve the design rule analysis of SEA and PCF for double-cell thin-walled tubes, respectively. Both models were trained through five-fold cross-validation, and a grid search was performed across candidate splitting criteria (information gain, gain ratio, and Gini index) and maximum tree depths ranging from 3 to 9 to identify the optimal model configuration.

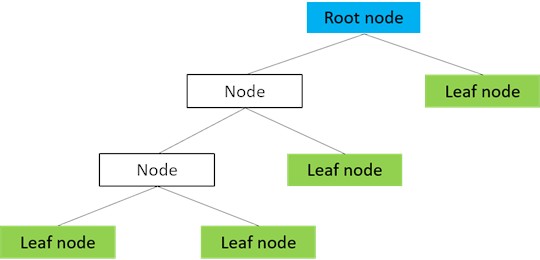

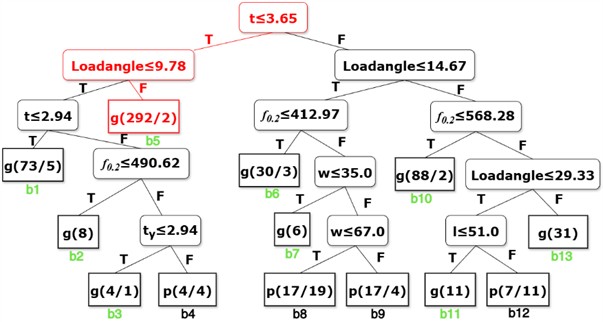

After cross-validation, the optimal parameters for the SEA model were as follows: the splitting criterion was the gain ratio, and the maximum tree depth was 6. The model achieved an average accuracy of 0.8656 and an average Brier score of 0.0699 across the five folds. On the independent test set ( 160), the accuracy and Brier score were 0.8562 and 0.0706, respectively. The optimal SEA decision tree is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8SEA decision tree. The denotation of the leaf node: Label (the number of designs in this leaf/the number of designs incorrectly classified)

For the PCF model, the optimal parameters were as follows: the splitting criterion was the Gini index, and the maximum tree depth was 5. The model achieved an average accuracy of 0.8922 and an average Brier score of 0.0532 during cross-validation, and an accuracy of 0.8938 with a Brier score of 0.0506 on the independent test set. The optimal PCF decision tree is illustrated in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9PCF decision tree

To enhance the statistical robustness of performance estimation, bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) was applied to derive 95 % confidence intervals for both metrics. For the SEA model, the 95 % confidence intervals for accuracy and Brier score were [0.8438, 0.9375] and [0.0335, 0.0718], respectively. For the PCF model, the corresponding intervals were [0.8750, 0.9313] and [0.0345, 0.0593].

Based on the above evaluation results, both the SEA and PCF models achieved accuracies exceeding 85 % and Brier scores below 0.1, demonstrating strong performance in prediction accuracy and statistical robustness. These results establish a reliable foundation for subsequent analyses.

4.4. Data mining of crashworthiness of double-cell thin-walled tubes

Based on the dataset comprising the design variables and corresponding responses of the double-cell thin-walled tubes, this study utilized the DTUD algorithm for data mining to analyze the design rules of the double-cell tubes, thereby identifying the critical design parameters influencing its crashworthiness and the corresponding reduced design domain.

By applying the DTUD algorithm to the dataset, decision trees for SEA and PCF were obtained, as illustrated in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9. Design variables are tested at non-leaf nodes, and structural performance is labeled at leaf nodes (g = “good,” m = “intermediate,” p = “poor”). The node splitting criteria are displayed along the path.

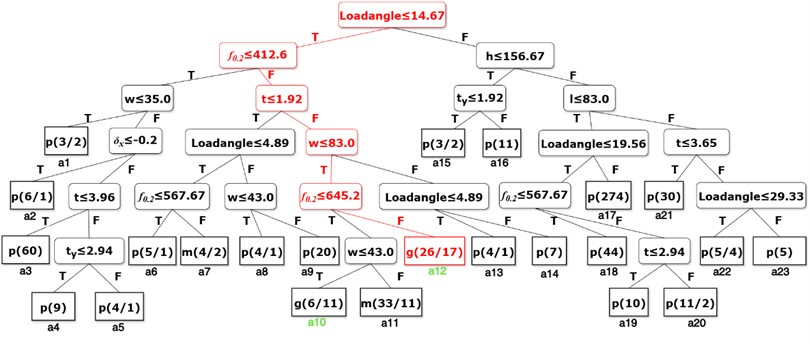

The SEA decision tree is illustrated in Fig. 8, with several branches (labeled a1 to a23). To enhance the collision resistance of thin-walled beams under oblique loads, it is desirable for SEA to be as large as possible, corresponding to the “good” classification path (a10, a12). To improve robustness, it is advisable to select paths with a high probability of being classified as “good” and containing a significant amount of data. The optimal path is marked in red (a12) in Fig. 8. Analysis of a12 yields the following design rules for a larger SEA: Load angle ≤ 14.67°, > 645.2 MPa, 1.92 mm, 83.0 mm. It is confirmed that f₀.₂, t, and w are the critical design parameters, with their influence on SEA decreasing in that order.

Similarly, the PCF decision tree is illustrated in Fig. 9, with several branches (labeled b1 to b13). To improve the crashworthiness of thin-walled tubes under oblique loads, it is desirable for the PCF to be as small as possible, corresponding to the “good” classification path (marked in green). To enhance robustness, the path with a higher probability of being classified as “good” and containing more data should be selected. The optimal path is marked in red(b5) in Fig. 9. Analysis of b5 yields the following design rules for a smaller PCF: 3.65 mm, Load angle > 9.78°. It is confirmed that t are the critical design parameters.

Table 2Comparison between the original design domain and the reduced design domain based on data mining

Design variables | Original design domain | Reduced design domain after data mining | ||

Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | |

/ mm | 1 | 5 | 1.92 | 3.65 |

/ MPa | 200 | 800 | 645.2 | 800 |

/ mm | 30 | 90 | 30 | 83.0 |

/ mm | 30 | 90 | 50 | |

/ mm | 150 | 300 | 150 | |

–0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | ||

/ mm | 1 | 5 | 1 | |

Based on the above analyses, this study aims to achieve double-cell tube design with excellent crashworthiness (SEA and PCF) under conditions where Load angle < 15°. Based on the results of the SEA and PCF decision tree, the three design variables , , and on design rules a12 and b5 are identified as critical design parameters. Among these, has the most significant impact on the collision resistance of double-cell tubes, followed by , and . Consequently, future design efforts should focus on these parameters. Additionally, based on the decision tree, the intersection of the parameter ranges obtained for a6 and b18 is taken to obtain a reduced range of values, as shown in Table 2, thereby achieving design domain reduction (DDR). The other four design variables (, , , and ) have no significant impact on the sizes of SEA and PCF. These can be selected with appropriate values based on engineering requirements, thereby reducing the effort invested in non-critical design parameters during the design process.

4.5. Comparison of design based on data mining driven design domain reduction and original design domain

To validate the performance of the data mining methods in improving design efficiency in this study, based on the above analysis, multi-objective optimization was conducted separately in the original design domain (ODD) and the reduced design domain (RDD) obtained through data mining for the multi-angle crashworthiness design of double-cell thin-walled beams. The results of the optimized designs were then compared.

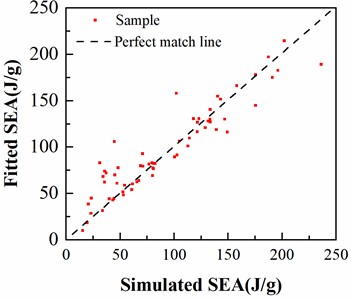

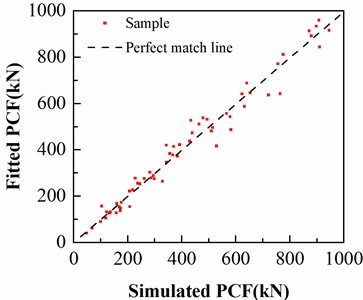

First, it is necessary to establish prediction models for SEA and PCF. Using the dataset generated by finite element simulations, construct polynomial surrogate models for SEA and PCF. A random selection of 60 points was used for error analysis to validate the accuracy of the surrogate models. Fig. 10 shows the comparison between the predicted values and simulation results of SEA and PCF, and the predicted values are generally close to the actual values. The value of the SEA surrogate model is 0.8627, and that of the PCF model is 0.9774. Both are greater than 0.85, which meets the requirements of the corresponding error analysis indicators. These surrogate models can replace finite element simulations for predicting performance objectives in subsequent optimization design.

Fig. 10Prediction results of RSM model

a) SEA

b) PCF

Based on the third-order polynomial surrogate models of SEA and PCF, the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) was adopted to perform multi-objective optimization in the original design domain (ODD) and the reduced design domain (RDD) obtained through data mining, to obtain the Pareto optimal solution sets. In this study, the population size of the NSGA-II algorithm was set to 50, the number of generations was 50, and the crossover probability was 0.9.

In theory, any point on the Pareto front can be regarded as an optimal point, but SEA increases usually cause PCF to increase as well, and an excessively high PCF may lead to high impact acceleration, which is unfavorable for passenger safety. Therefore, the TOPSIS method was used to assign weights to performance objectives based on actual engineering requirements and select the optimal solution from the Pareto solution set. In this study, the weights of SEA and PCF were 0.6 and 0.4, respectively. The optimal design schemes and crashworthiness indicators predicted by the RSM model under ODD and RDD are shown in Table 3. Finite element simulations were performed based on the design variable values of the optimal schemes, and the results are shown in Fig. 11, Table 3, and Table 4. The results show that the prediction errors of SEA and PCF in the optimal design under ODD were –6.82 % and –5.60 %, respectively, while those under RDD were –7.85 % and –8.47 %, respectively, all within the allowable range of less than 10 %, indicating that the obtained optimal design schemes are reliable.

Table 3Optimal results based on ODD and RDD, and Crashworthiness metrics predicted by the RSM model

ODD | RDD | ||

Design variables | / mm | 48 | 50 |

/ mm | 30 | 30 | |

/ mm | 150 | 150 | |

-0.04 | 0 | ||

/ mm | 3.86 | 3.65 | |

/ mm | 1.01 | 1 | |

/ MPa | 800 | 800 | |

Crashworthiness response (Load Angle = 10°) | SEA / (J/g) | 217.67 | 214.33 |

PCF / kN | 480.78 | 456.82 |

Fig. 11Comparison of deformation modes: Initial design, optimal design based on ODD and RDD

a) Initial

b) ODD

c) RDD

Table 4Comparison of optimal results based on ODD and RDD

Simulated SEA / (J/g) | Relative to the initial value | Simulated PCF / kN | Relative to the initial value | Iterations required for convergence | |

Initial | 163.56 | – | 500.09 | – | – |

ODD | 232.51 | 42.16 % | 507.7 | –1.52 % | 20 |

RDD | 216.01 | 32.07 % | 432.87 | –13.44 % | 2 |

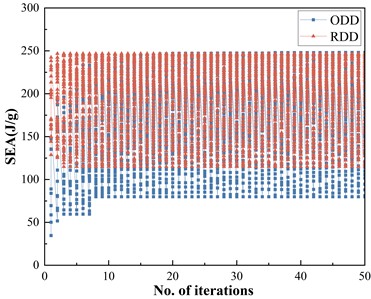

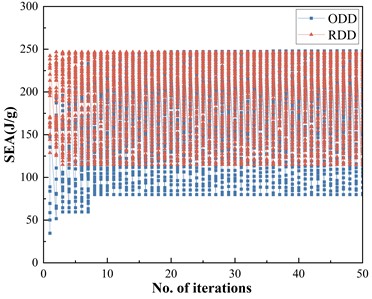

Fig. 12The iteration histories of multi-objective optimization in data mining-based reduced design domain (RDD) and the original design domain (ODD)

a) SEA iteration histories

b) PCF iteration histories

The simulation results of the optimal design schemes under ODD and RDD are compared with the optimal design in the initial dataset, as shown in Table 4. The optimal design scheme obtained through multi-objective optimization based on data mining under RDD improved the SEA by 32.07 % compared to the initial design, while the PCF increased by 13.44 %, indicating that the overall crashworthiness performance of the optimal design under RDD conditions is superior to that of the optimal design in the initial dataset and is comparable to the optimization effect under ODD conditions. This validates the effectiveness of this decision tree-based data mining method for design optimization.

In addition, the convergence speed of the optimization under ODD and RDD was compared. Fig. 12 shows the iteration history of the two optimization methods. As can be seen, under the same optimization effects, the data mining-based optimization methods SEA and PCF converged in the 2th and 3th iterations, respectively, which was much faster than the ODD-based optimization method, which converged after the 20th and 15th iterations. This indicates that the data mining method employed in this study can effectively identify critical design parameters and design rules, thereby significantly enhancing design efficiency in practical design processes.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a decision-tree-based data-mining methodology is developed to address the crashworthiness design of automotive dual-cell thin-walled tubes subjected to oblique loading. In contrast to conventional parameter-optimization strategies, this method not only enables structural optimization but, more importantly, extracts design rules directly from simulation data. This capability facilitates critical parameter identification and design domain reduction, thereby enhancing the efficiency of the design process.

This study takes the crashworthiness design of double-cell thin-walled tubes as a case study. Geometric and material properties of the tube are defined as design variables, whereas maximizing the specific energy absorption and minimizing the peak crushing force are specified as the performance objectives. Through data mining of finite-element simulation data, the method establishes an interpretable mapping between design variables and crashworthiness responses, yielding actionable insights for engineering design. The study identifies three critical design parameters and the reduced design domain.

Furthermore, multi-objective optimization is performed within both the reduced design domain derived from data mining and the original domain. The results show that the optimization efficiency of the data-mining-based method is nearly ten times higher than that of traditional approaches, while ensuring the optimization effect (SEA: +32.07 %, PCF: –13.44 %). This method effectively shortens the development cycle and reduces reliance on repeated simulations and crash tests, providing a new approach for automotive crashworthiness design.

The data-driven design philosophy demonstrated in this method is readily extendable to complex engineering systems involving multiple objectives and constraints, providing a transferable and interpretable solution for crashworthiness-oriented and other performance-critical structural design problems.

References

-

R. Yao, T. Pang, B. Zhang, J. Fang, Q. Li, and G. Sun, “On the crashworthiness of thin-walled multi-cell structures and materials: State of the art and prospects,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 189, p. 110734, Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2023.110734

-

H.-S. Kim, “New extruded multi-cell aluminum profile for maximum crash energy absorption and weight efficiency,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 311–327, Apr. 2002, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0263-8231(01)00069-6

-

X. Zhang and G. Cheng, “A comparative study of energy absorption characteristics of foam-filled and multi-cell square columns,” International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 34, No. 11, pp. 1739–1752, Nov. 2007, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2006.10.007

-

M.-S. Gulino, L. D. Gangi, A. Sortino, and D. Vangi, “Injury risk assessment based on pre-crash variables: The role of closing velocity and impact eccentricity,” Accident Analysis and Prevention, Vol. 150, p. 105864, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2020.105864

-

A. Reyes, M. Langseth, and O. S. Hopperstad, “Crashworthiness of aluminum extrusions subjected to oblique loading: experiments and numerical analyses,” International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 44, No. 9, pp. 1965–1984, Sep. 2002, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7403(02)00050-4

-

T. Tran, S. Hou, X. Han, N. Nguyen, and M. Chau, “Theoretical prediction and crashworthiness optimization of multi-cell square tubes under oblique impact loading,” International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 89, pp. 177–193, Dec. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2014.08.027

-

D. C. Han and S. H. Park, “Collapse behavior of square thin-walled columns subjected to oblique loads,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 167–184, Nov. 1999, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0263-8231(99)00022-1

-

A. Reyes, M. Langseth, and O. S. Hopperstad, “Square aluminum tubes subjected to oblique loading,” International Journal of Impact Engineering, Vol. 28, No. 10, pp. 1077–1106, Nov. 2003, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0734-743x(03)00045-9

-

J. Zhang, J. Xie, T. Zhang, B. Lu, D. Zheng, and H. Zhou, “A prediction method for oblique load stability of multi-cell tubes based on SVM,” Engineering Structures, Vol. 283, p. 115885, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.115885

-

H.-S. Kim and T. Wierzbicki, “Crush behavior of thin-walled prismatic columns under combined bending and compression,” Computers and Structures, Vol. 79, No. 15, pp. 1417–1432, Jun. 2001, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0045-7949(01)00045-1

-

J. Zhang, D. Zheng, B. Lu, and T. Zhang, “Energy absorption performance of hybrid cross section tubes under oblique loads,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 159, p. 107133, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2020.107133

-

T. Tran, “Study on the crashworthiness of windowed multi-cell square tubes under axial and oblique impact,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 155, p. 106907, Oct. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2020.106907

-

S. Tabacu, “Analysis of circular tubes with rectangular multi-cell insert under oblique impact loads,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 106, pp. 129–147, Sep. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2016.04.024

-

H. Yin, G. Wen, Z. Liu, and Q. Qing, “Crashworthiness optimization design for foam-filled multi-cell thin-walled structures,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 75, pp. 8–17, Feb. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2013.10.022

-

R. Toledo, J. J. Aznárez, O. Maeso, and D. Greiner, “Optimization of thin noise barrier designs using Evolutionary Algorithms and a Dual BEM Formulation,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 334, pp. 219–238, Jan. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsv.2014.08.032

-

X. Du, F. Zhu, and C. C. Chou, “A new data-driven design method for thin-walled vehicular structures under crash loading,” SAE International Journal of Transportation Safety, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 188–193, Mar. 2017, https://doi.org/10.4271/2017-01-1463

-

S. Bagheri, W. Konen, and T. Back, “Online selection of surrogate models for constrained black-box optimization,” in IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), pp. 1–8, Dec. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/ssci.2016.7850206

-

J. Fang, Y. Gao, G. Sun, N. Qiu, and Q. Li, “On design of multi-cell tubes under axial and oblique impact loads,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 95, pp. 115–126, Oct. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2015.07.002

-

Q. Liu, K. Liufu, Z. Cui, J. Li, J. Fang, and Q. Li, “Multiobjective optimization of perforated square CFRP tubes for crashworthiness,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 149, p. 106628, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2020.106628

-

G. J. Sequeira and T. Brandmeier, “Evaluation and characterization of crash-pulses for head-on collisions with varying overlap crash scenarios,” Transportation Research Procedia, Vol. 48, pp. 1306–1315, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2020.08.156

-

L. Ke, H. B. Qiu, Z. Z. Chen, and L. Chi, “Engineering design based on Hammersley sequences sampling method and SVR,” Advanced Materials Research, Vol. 544, pp. 206–211, Jun. 2012, https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.544.206

-

X. Du, H. Xu, and F. Zhu, “A data mining method for structure design with uncertainty in design variables,” Computers and Structures, Vol. 244, p. 106457, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2020.106457

-

M. S. Aslam and Z. Ma, “Output regulation for time-delayed Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy model with networked control system,” Hacettepe Journal of Mathematics and Statistics, Vol. 52, No. 5, pp. 1282–1302, Oct. 2023, https://doi.org/10.15672/hujms.1017898

-

J. Han, J. Pei, and M. Kamber, Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques. United States: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc, 2006.

-

H. Wei, H. Wang, Z. Wen, Y. Peng, H. Wang, and F. Sun, “A crashworthiness design framework based on temporal-spatial feature extraction and multi-target sequential modeling,” Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 206, p. 112694, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.112694

-

T. Tran and A. Baroutaji, “Crashworthiness optimal design of multi-cell triangular tubes under axial and oblique impact loading,” Engineering Failure Analysis, Vol. 93, pp. 241–256, Nov. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2018.07.003

-

J. Gajewski, M. Rogala, and D. Vališ, “Application of neural networks specific forms for estimation of crushing signal parameters of multilevel structural absorbers implemented in passive safety research,” Measurement, Vol. 242, p. 115817, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115817

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Hongbin Tang: investigation, methodology, conceptualization, writing original draft. Xue Bai: conceptualization, writing-reviewing and editing, writing original draft. Ledan Liu: investigation, methodology, writing-reviewing and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.