Abstract

The enhancement of guide rail strength for ball rolling applications is crucial to improving the durability and operational efficiency of the manufacturing process. One effective method for achieving this is carbonitriding, a chemical-thermal treatment that forms a hardened surface layer by saturating the material with both carbon and nitrogen at relatively low temperatures. This study was aimed at improving the mechanical properties of the guide bar used to hold balls on the rolling axis in ball rolling mills by chemical-thermal strengthening-carbonitration. Specimens of mild and medium carbon steel were used as tests. The process consisted in immersing the specimens in a bath with molten salts at a temperature of 570 °C and holding for 1.5 hours. The samples were then cooled in oil and then cleaned with high-pressure water. The study showed that the melt of salts based on urea and potassium carbonate saturates the steel surface with nitrogen and carbon, forming a hardened layer. The depth of the hardened layer depends on the exposure time, but after one hour, the penetration of diffusing substances slows down. This is due to the saturation of the steel crystal lattice with alloying elements (carbon and nitrogen) during carbonitration. The maximum hardening depth for high-alloy tool steels is 0.05-0.12 mm, for carbon steels 0.1-0.6 mm. Carbonitration can be used to increase the hardness, strength, wear resistance of balls without increasing the brittleness of the part.

1. Introduction

Improving the mechanical strength of the guide ruler used in ball rolling in a ball rolling mill is a critical factor in increasing the service life and overall efficiency of the production process. One of the most effective methods of improving the performance of steel, is the use of chemical heat treatment, known as carbonitriding. This process allows the formation of a hard, wear-resistant and corrosion-resistant surface layer by saturating the surface of the material with carbon and nitrogen at relatively low processing temperatures.

Carbonitration is the process of hardening the surface layer of steel by immersing it in a melt of potassium cyanate (KOCN) and potassium carbonate salt (K2CO3) at a temperature of 570-580 ℃ with a holding time of about one hour [1, 2]. During the carbonitriding process, a hardened layer consisting of several distinct zones is formed on the steel surface. The uppermost layer represents a carbonitride phase of the Fe(N,C) type, beneath which lies a diffusion (heterogeneous) zone composed of a solid solution of carbon and nitrogen in iron with dispersed carbonitride inclusions. The hardness of this diffusion zone is significantly higher than that of the core material. For high-alloy tool steels, the maximum hardening depth ranges from 0.05 to 0.12 mm, while for carbon steels, it ranges from 0.1 to 0.6 mm. Carbonitriding enhances surface hardness, strength, and wear resistance without significantly increasing the brittleness of the treated components [3, 4].

2. Methods

Proposed Technology: Following thermal and mechanical treatment, the centering guide rail is placed in an electric furnace and heated to a temperature of 450-500 °C to relieve residual stresses and to ensure thorough removal of surface moisture. The component is then immersed in a carbonitriding bath maintained at 570 °C and held for 1.5 hours. After carbonitriding, the component is transferred to an oil bath for slow cooling and subsequently cleaned of soot using high-pressure water spray equipment.

Laboratory Investigation: The primary objective of the experimental work was to prepare a chemically active molten salt mixture based on urea (CO(NH2)2), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and sodium chloride (NaCl), in order to perform carbonitriding on a steel macrosection and evaluate changes in surface hardness. The study aimed to assess the effectiveness of the chemical-thermal hardening process by comparing hardness values before and after treatment.

Experimental Procedure: To prepare the molten mixture with the required chemical composition, data from source [5] were used. The quantities of the components and the relevant chemical reactions are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1Melt composition

Component | Amount, g | Proportion, % |

CO(NH2)2 | 90 | 42.86 |

NaHCO3 | 80 | 38.1 |

NaOH | 20 | 9.52 |

NaCl | 20 | 9.52 |

TOTAL | 210 | 100 |

Table 2Chemical reactions in the melt

No. | Reaction equation |

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

5 | |

6 |

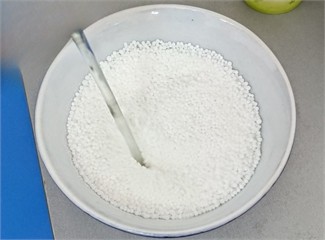

At the first stage, the melt was prepared and the hardness of the steel macrosection was measured using an HRC-scale hardness tester. All reagents were precisely weighed on a laboratory scale and thoroughly mixed in a ceramic container (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1Component preparation process. Photo taken by M. Z. Ubaydullaev (co-author) in the laboratory of the Almalyk Branch of NUST MISIS, 2025

At the second stage, the mixture of substances was transferred into a steel crucible and placed in a muffle furnace to initiate the melting process. Along with the crucible, the steel macrosection was also placed into the furnace for heating and moisture removal from its surface. The furnace had been preheated in advance, and the chamber temperature was set to 580 °C [6].

At the third stage, the salt mixture was fully melted after exactly one hour in the muffle furnace. The preheated steel macrosection sample was then immersed in the resulting melt for a duration of two hours. Fig. 2 shows the steel crucible containing the melt and the sample. Fig. 3 presents a top view of the melt, where additional samples intended for future impact toughness testing can be seen. The furnace temperature during this stage was also maintained at 580 °C [7].

Fig. 2Sample and steel crucible in the muffle furnace. Photo taken by M.Z. Ubaydullaev (co-author) in the laboratory of the Almalyk Branch of NUST MISIS, 2025

Fig. 3Top view of the melt with various samples. Photo taken by M.Z. Ubaydullaev (co-author) in the laboratory of the Almalyk Branch of NUST MISIS, 2025

At the fourth stage, after two hours, the crucible was removed from the furnace, and the sample was subjected to oil quenching, as shown in Fig. 4. Subsequently, the sample was washed with water and the surface was polished to remove the formed soot [8].

Fig. 4Oil quenching process. Photo taken by M.Z. Ubaydullaev (co-author) in the laboratory of the Almalyk Branch of NUST MISIS, 2025)

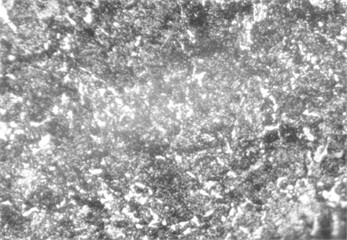

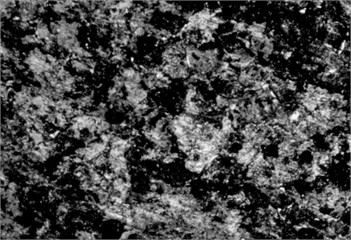

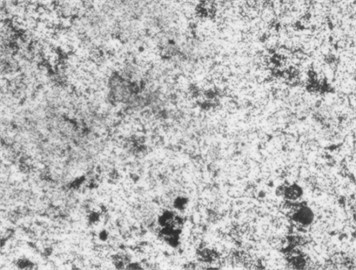

At the fifth stage, hardness measurements were conducted and the microstructure was examined. The data are presented in Table 3, while the microstructure is shown in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 [9].

Table 3Average hardness before and after carbonitriding

Before carbonitriding | After carbonitriding | ||||

Sample type | HRC | HB | Sample type | HRC | HB |

Low-carbon steel | 13.15 | 190 | Low-carbon steel | 17.25 | 208 |

Medium-carbon steel | 25.4 | 250 | Medium-carbon steel | 27.8 | 262 |

Fig. 5Microstructure before carbonitriding. Photo taken by M.Z. Ubaydullaev (co-author) in the laboratory of the Almalyk Branch of NUST MISIS, 2025

a) Low-carbon steel

b) Medium-carbon steel

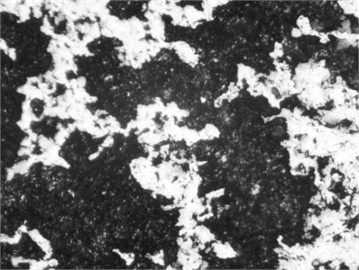

Fig. 6Microstructure after carbonitriding. Photo taken by M.Z. Ubaydullaev (co-author) in the laboratory of the Almalyk Branch of NUST MISIS, 2025

a) Low-carbon steel

b) Medium-carbon steel

Possible sources of experimental error may include slight deviations in the weight of salts during mixture preparation, which can affect the chemical composition and reactivity of the molten bath. Variations in the actual temperature and holding time may also influence the diffusion rate of carbon and nitrogen, leading to differences in the thickness of the hardened layer. Additionally, inaccuracies during hardness measurement – caused by surface roughness, uneven polishing, or indentation placement – can result in minor discrepancies in the obtained HRC and HB values. Consequently, the observed variations in hardness and diffusion layer thickness should be considered within the limits of experimental uncertainty.

3. Results and discussion

During thermal decomposition at 160 °C, urea breaks down into isocyanic acid and ammonia gas. The isocyanic acid then reacts with sodium carbonate (a decomposition product of NaHCO3 at 200 °C), forming sodium cyanate (NaOCN), a key agent in the carbonitriding process. At 580 °C, sodium cyanate undergoes oxidation, releasing nitrogen and partially carbon atoms, which diffuse into the steel surface, enhancing hardness and mechanical strength. NaCl and NaOH are added to stabilize the melt temperature, as urea rapidly decomposes above 160 °C.

The initial surface structure of the low-carbon steel (Fig. 5) shows a ferrite–pearlite composition, while the medium-carbon steel exhibits a pearlite structure with ferritic inclusions. Due to the lower carbon content, the low-carbon steel contains more ferrite grains – softer and more ductile but less wear-resistant. After carbonitriding (Fig. 6), both samples display surface zones consisting of -carbonitride Fe3(N,C) and a subsurface -phase Fe4(N,C), with a total thickness of approximately 11 µm and a hardened layer depth of ~0.3 mm.

Table 4Tensile test results

Condition | Max load, kN | Ultimate strength, MPa | Elongation, % | Hardness HRC (HRB) |

Without carbonitriding | 21.22 | 530 | 51.28 | 5.8 (166) |

Carbonitriding – 1 hour | 22.97 | 574 | 46.57 | 14.4 (191) |

Carbonitriding – 2 hours | 30.58 | 581 | 50.97 | 21 (229) |

4. Conclusions

Carbonitriding of low- and medium-carbon steels at 570-580 °C for 1.5-2 hours in a molten salt bath composed of CO(NH2)2, NaHCO3, NaOH, and NaCl led to the formation of a 0.3 mm hardened layer, increasing hardness from 13.15 HRC to 17.25 HRC for low-carbon steel and from 25.4 HRC to 27.8 HRC for medium-carbon steel. The ultimate tensile strength rose from 530 MPa to 581 MPa, and the maximum load increased from 21.22 kN to 30.58 kN. These results confirm that the proposed chemical-thermal treatment effectively enhances the surface hardness, strength, and wear resistance of steel guide rails, thereby extending their service life and reliability.

References

-

V. A. Korotkov, Technical and Economic Efficiency of Carbonitriding. Moscow, Russia: Vestnik Mashinostroeniya, 2017.

-

W. Thermochim, “Description of Carbonitration,” 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yyipe7g5DvQ

-

I. L. Yakovleva, N. A. Tereshchenko, A. V. Stepanchukova, E. Y. Priymak, and Y. A. Chirkov, “Structure and wear resistance of nitrocarburized medium-carbon steels,” Metal Science and Heat Treatment, Vol. 59, No. 9-10, pp. 630–636, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11041-018-0202-9

-

“Thermomechanically hardened reinforcing steel for reinforced concrete structures,” Standartinform, Moscow, Russia, GOST 10884-94, 2009.

-

“Solid-Rolled Wheels,” Standartinform, Moscow, Russia, GOST 10791-2004, 2006.

-

S. G. Tsikh, V. I. Grishin, A. V. Supov, V. N. Lisitskii, and Y. A. Glebova, “Advancement of the process of carbonitriding,” Metal Science and Heat Treatment, Vol. 52, No. 9-10, pp. 408–412, Jan. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11041-010-9292-8

-

D. A. Prokoshkin, Chemical-Thermal Treatment of Metals – Carbonitriding. Moscow, Russia: Metallurgy/Mashinostroenie, 1984.

-

Y. M. Lakhtin and V. P. Leontyeva, Materials Science. Moscow, Russia: Wiley, 1990.

-

M. V. Mogilenets, “Carbonitration in molten salts,” Equipment and Tools for Professionals, pp. 1–52, 2018.

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.