Abstract

In this paper, extensive numerical investigations into reinforced concrete beam made of lightweight concrete are given, through the ANSYS finite element program. The main aim was to assess the load carrying capacity, stiffness and deformation characteristics of the beams of different concrete densities. There were seven beam specimens, which vary in the percentage ratio of lightweight to normal aggregates, and the material properties were duly incorporated in the model. Three-dimensional nonlinear finite element analysis was used to simulate the beams with a mesh size of 25 mm, and the results were compared with the experimental results. Results showed that when the concrete density was reduced the loadbearing capacity decreased gradually, as the concrete became normal weight (95 kN) and then fully lightweight (85.7 kN). Nevertheless, the plastic zone transition happened later in lightweight beams and this implies that the deformation resistance was more difficult than in normal-weight concrete. The load-deflection curve demonstrated the fact that lightweight concrete beams though less stiff in nature, are structurally reliable and competitive. This study highlights the possibility of the lightweight concrete to be used as a structural material in contemporary engineering practice and therefore seismic zones where minimized self-weight improves the overall safety and efficiency. The results are useful in understanding how to optimize and design the reinforced lightweight concrete members.

1. Introduction

Beams of reinforced concrete have been consistently of special concern to the construction industry as one of the primary load carrying components. Over the past few years, in addition to typical normal weight concrete, the application of lightweight concrete structural members has become a relatively growing trend. Lightweight concrete mainly has the merits of low weight density, high thermal and acoustic insulation, economical nature, and more importantly, the possibility of decreasing the total weight of the structures within seismic territories. Parameters like compressive strength, modulus of elasticity and resistance to deformation might however be slightly less than the normal-weight concrete. Thus, to make sure of their credible performance, it is critical to perform thorough analyses with the help of contemporary numerical modeling tools.

In this light, over the past few years, scholars have carried out several studies in which they modeled lightweight concrete beam using the ANSYS software. Specifically, reinforced concrete beam produced using lightweight concrete, including the expanded polystyrene (EPS) and montmorillonite additives, were thoroughly analyzed in the paper by Surjith Singh Raja and J. Saravanan [1]. ANSYS was used to create a nonlinear finite element method (FEM) model to study the loaddeflection behavior and the distribution of stress in the steel reinforcement. The study results showed that the numerical simulation had high level of correlation with the experimental data and could give reliable predictions even at the post-yield deformation stage [2]. The study has offered an appropriate representation of the effects of different lightweight concrete modifications on the structural strength of the beam, which can be utilized as a sound methodological foundation to select materials to use in future construction projects.

Mohamed A. El Zareef [3] provided an experimental study into the flexural behavior, the stages of failure and performance of reinforced concrete beams assembled on light weight concrete of a cylindrical compressive strength of 30 Mpa with the reinforcement of glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars. They were compared to the beams of the same compressive strength (30 MPa) reinforced with conventional steel bars and composed of the normal-weight concrete. Despite the fact that the experimental results were analyzed with the DIANA finite element software, the obtained results were also observed to be in high agreement with the results that would have been obtained through calculations with ANSYS, which underscores the consistency of the methodologies. The experiment comprehensively studied the effect of the kind of reinforcement on the load bearing capacity and tensile deformation behavior of the beams. The findings showed that GFRP reinforcement has the potential of being more efficient than steel reinforcement in structural elements cast with lightweight concrete. Moreover, the analysis of lightweight aggregate concrete and normal-weight concrete beam drawing found that the ultimate load bearing capacity, flexural ductility, crack propagation behavior and failure mode of both were similar which proved the lightweight concrete could be used in confident structural practices [4].

Ade Sriwahyuni, Vanissorn Vimonsatit, and Hamid Nikraz [5] applied the ANSYS 12.1 program to examine the structural efficiency of lightweight sandwich beams constructed of autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC). They used nonlinear finite element analysis (FEA) in their study to identify a bending moment, deflection behavior, and deformation pattern that occurred in the beams. The results of the research stated that at the early loading stages, the numerical modeling results were well in agreement with the experimental data. Nevertheless, upon crack initiation, visible changes were also noticed and the authors explained it by the heterogeneous nature of the microstructure of concrete and the inability to reliably predict micro-deformations in the computational model. The research was a valuable scientific basis of knowing the issues surrounding the nonlinear analysis of lightweight concrete beam, and that further sophisticated methods of its modeling are required to reflect the post-cracking behaviour of the elements made of AAC-based structure.

An experimental study was done by Abdullah Basil Raheem and Fadya S. Klak [6] to determine the shear strength behavior of I-shape lightweight concrete beam reinforced with the addition of steel and glass fibers in different fraction of volumes. The 75 per cent of the ordinary coarse aggregates were substituted with the lightweight aggregates in the preparation of lightweight concrete with both the control specimen (normal-weight concrete) and the lightweight concrete sample being set to reach a compressive strength of 30 MPa. The numerical simulations of the ANSYS finite element software were also compared with the experimental results. It was noted that, addition of 0.5 % of steel fibers to normal weight concrete, 1 % of steel fibers, 1.5 % of steel fibers, shear strength along the diagonal section increased by 3.5 %, 13.5 and 13.3 respectively as compared to the specimens that were not added with the fibers. The same was also observed in the lightweight concrete beams [7-9]. The overall results revealed that fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete has a similar and competitive shear strength performance to standard weight concrete, which supports its structural integrity and the possibility of being used in the construction industry today [10, 11].

2. Method

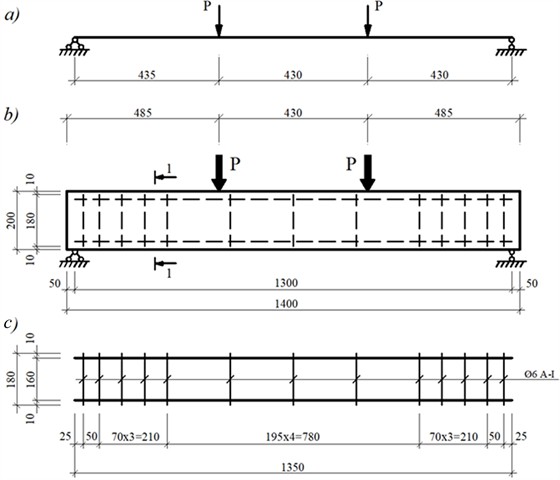

It is an analytical model of a beam that was designed as a simply supported beam with a rectangular section whose geometrical dimensions, loading configuration and reinforcement layout is shown in Fig. 1. According to this model, the distribution laws of normal stresses, deformations and crack propagation were studied in detail. The acquired data allowed to obtain credible simulation results in ANSYS, as long as the geometric and physico-mechanical parameters were correctly specified through the modelling procedure. The characteristics of the beams used in the modeling process are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1The calculation scheme of the beam and the location of the reinforcement frame in it: a) calculation scheme; b) placing the load on the beam; c) rebar frame

Table 1Characteristics of beams

Naming of the beam | Average bulk density, kg/m3 | Cubic strength , MPa | Prismatic strength in compression , MPa | Prismatic tensile strength , MPa | Modulus of elasticity , MPa |

B1-L0/H100 | 2515 | 48.89 | 35.24 | 2.61 | 35416 |

B2-L50/H50 | 2092 | 40.63 | 29.52 | 2.46 | 33502 |

B3-L60/H40 | 1925 | 37.42 | 27.23 | 2.42 | 32685 |

B4-L70/H30 | 1861 | 34.51 | 25.18 | 2.36 | 31902 |

B5-L80/H20 | 1798 | 30.14 | 22.09 | 2.26 | 30630 |

B6-L90/H10 | 1702 | 27.66 | 20.33 | 2.18 | 29851 |

B7-L100/H0 | 1632 | 23.30 | 17.17 | 2.12 | 28354 |

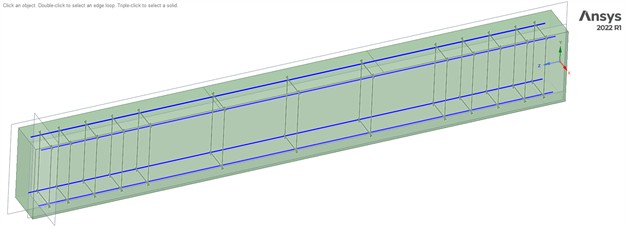

The model and analysis of these reinforced concrete beams in ANSYS was performed through three-dimensional finite element analysis, with the finite element mesh size being fixed to 25 mm (as seen in Fig. 2). The reinforcement cage during the modelling process was such that it would agree with the dimensions applied during the experimental tests. The physico-mechanical properties of all the constituent materials used were taken into account keenly to yield results that accurately depict real structural behaviour in the simulation process.

3. Results and discussion

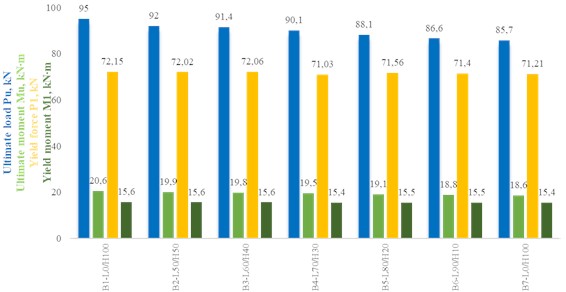

Based on the research results, the reduction in the load-carrying capacity with the decrease in concrete density was also consistent. The normal-weight concrete beam had the greatest load capacity of 95kN, whereas the beam of B7-L100/H0 series, manufactured with lightweight aggregates, showed the least of 85.7 kN. Fig. 3 shows the values of the ultimate load and the respective limiting bending moment of the reinforced concrete beams as well.

Fig. 2Finite element model of the beam and reinforcement frame in ANSYS

Fig. 3Destructive load and ultimate moment values in reinforced concrete beams

Fig. 4Changes in ductility when steel reinforcement reaches the yield point and fails under loading in beams

The peak deflection of the normal-weight concrete beam was 25.68 mm with 19.95 mm in the lightweight concrete beam. The deflection due to the corresponding reinforcement yield limit however had an opposite trend-3.11 mm and 3.48 mm in the normal and lightweight concrete beam respectively. With a B1-L0/H100 beam, the deflection at the steel yield point (f1) contributed 12.1 percent of the total deflection, compared to the range of 13.4 percent to 17.4 percent in other specimens. As such it can be concluded that as the concrete density increases the overall deflection increases. Meanwhile, the reinforcement yield limit deflection is a major indicator of beam rigidity and is widely used in design calculation as the load carrying capacity. Fig. 4 shows the respective deflection values of all the beams.

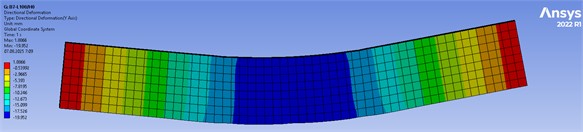

The load carrying capacity of the beams also rose gradually at the initial loading stage within the elastic working range of the steel reinforcement. In this stage, beams were at their highest level of stiffness and they were also stable in their performance due to the loads that were applied. Nevertheless, when the force on the reinforcement hit the yield limit, which was the point of the start of plastic deformations, the overall stiffness of the beams became discernibly lower. Fig. 5 depicts the behavior of the B7-L100/H0 beam under ultimate (failure) load under deflection.

Fig. 5Formation of deflection under destructive load on a B7-L100/H0 beam

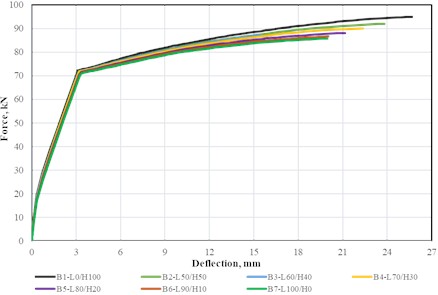

It was observed that the load carrying capacity of the beams grew progressively in the elastic range of the steel reinforcement at the first stage of loading. The beams were stiffest during this stage, meaning that they had sufficient resistance to the forces exerted on them. But, as the stress in the steel reinforcement reached its yield point, causing the onset of plastic deformations, the overall stiffness of the beams was gradually reduced. Fig. 6 gives the generalized version of the load-deflection diagram of reinforced concrete beam of various unit weights.

Fig. 6Load-deflection diagram

In the B1-L0/H100 normal-weight concrete beam, the gradual change to the plastic zone (i.e. the stiffness reduction) was initiated at 0.77 Pu, and in the B7-L100/H0 beam made of lightweight concrete, it happened later-at 0.083 Pu. This implies that the deformation resistance in normal weight concrete is lessened sooner than it is in light weight concrete. This is a behavior that is of great concern in the determination of the overall strength and stiffness of beams. In addition, post-yield behaviour of reinforcement is not normally taken into account in theoretical calculations, as at this point the structure experiences irretrievable deformations, indicating the end of its design load-carrying ability. Consequently, the graphical method of examining the loaddeflection relationship through such a diagram presents useful scientific and practical information in evaluating the structural performance during loading and in designing the optimum solutions to reinforced concrete beams.

4. Future scope

The results of this experiment have a strong basis to do additional numerical and experimental work on the topic of lightweight reinforced concrete beams. Three directions should be considered in future research because they are the ones that need improvement in terms of understanding and application. First, dynamic and cyclic characteristics of lightweight beams in seismic loading and repeated loading should be investigated. Due to the extensive use of lightweight elements in the seismic areas, time-history and modal studies can offer effective information about the fatigue strength, energy loss and general durability of the element under actual loading conditions. Second, the models of constitutive materials used in finite element models ought to be further improved. Defining material parameters better, and use of more complex models, such as microstructural heterogeneity, crack propagation, and time-dependent factors (such as creep, shrinkage), will help provide much better modeling accuracy and predict performance (long-term) much better. Lastly, hybrid reinforcement optimization is to be taken into consideration. As a further extension of the numerical modeling methodology to a set of reinforcement ratios, arrangements of bars, and combinations of steel and fiber-reinforced polymers will assist in streamlining structural design and reducing the amount of material used without reducing the safety level. There are also further studies in the future that may double the modeling of more intricate geometries like T-beams, L-beams and composite sections to enhance the relevance of the research findings to actual structures.

The other important future work opportunity is to investigate the impact of various forms of lightweight aggregates and additives. The performance of lightweight concrete in terms of its mechanical performance is mostly determined by the nature of its aggregates, including its density, rate of absorption and strength of its bondage to the cement matrix. By comparing experimental results with natural (e.g. pumice or volcanic ash) and artificial (e.g. expanded clay, shale or polystyrene beads) lightweight aggregates, it might be possible to understand the effects of microstructural variations on the behavior of stiffness, ductility and cracking. Nanomaterials or auxiliary cementitious materials can also be added to the mixture to improve the mechanical and durability performance, and this must be confirmed using coupled experimental numerical studies. Also, the communication between the lightweight concrete beams and the ambient conditions (temperature changes, humidity and contact with aggressive substances, chlorides, sulfates or carbonation) should be further researched. The degradation of materials in the long run has a great impact on the stiffness and the load carrying capacity of the beams. Thus, incorporating the thermo-mechanical and durability studies into the mesh structure may be a significant move in designing a sustainable and robust lightweight concrete structure.

5. Conclusions

1) The research results of the study show that the decrease in concrete density results in a steady decrease in the load-carrying capacity of reinforced concrete beams. Nevertheless, even beams manufactured using lightweight concrete had enough strength and stiffness, and had significant benefits in terms of reduced self-weight, ease of transportation, and seismic. These results affirm the possibility of the lightweight concrete as a logical substitute to the normal weight concrete in the construction field.

2) The ANSYS program also demonstrated its ability to accurately simulate the actual behavior of reinforced concrete beams as seen in the three-dimensional finite element modeling that was conducted with the ANSYS software and showed a high level of agreement with experimental results. It was demonstrated that the numerical model was capable of reproducing much of the stress distribution, the deformation pattern and the cracking progression, proving that ANSYS-based nonlinear analysis can be a strong analytical tool in predicting and optimizing the beam behavior in engineering design.

3) The experimental data proved that the experiment with the transition to the plastic deformation stage was observed at the higher load ratio in lightweight reinforced concrete beams (0.83 Pu) than in normal-weight beams (0.77 Pu), which showed more ductility and capacity to deform. That is a behavior that is tied to the internal microstructure of lightweight concrete that offers better stress redistribution and better energy absorption with increasing loads. Engineering wise, these properties indicate that lightweight concrete may be utilised successfully to decrease the total structural mass resulting in the saving of materials and expenses without compromising on the strength. Moreover, the high ductility and energy absorption capacity has led to a higher seismic performance thus, lightweight concrete beam is practical and efficient because of their seismic and energy saving features.

4) The load-deflection relationship study revealed that after the reinforcement reached its yield point, the total stiffness of the beams decreased considerably and irreversible deformations began. Even though this post yield phase is not normally featured in theoretical design, the numerical outcomes of this stage give significant information on the residual strength and deformation capability of the beams. The results are part of a more in-depth knowledge of the structural behaviour of lightweight concrete members and in the process, facilitate the formulation of the most ideal design plans as far as their application is concerned.

References

-

R. P. Surjith Singh Raja and J. Saravanan, “Finite element analysis of EPS based lightweight reinforced concrete beams using ANSYS,” Journal of Harbin Engineering University, Vol. 45, pp. 298–309, 2024.

-

A. Martazaev and S. Khakimov, “Dispersed reinforcement with basalt fibers and strength of fiber-reinforced concrete beams,” in The 3rd International Symposium on Civil, Environmental, and Infrastructure Engineering (ISCEIE) 2024, Vol. 3317, p. 030011, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0266797

-

El Zareef and Mohamed A., “An experimental and numerical analysis of the flexural performance of lightweight concrete beams reinforced with GFRP bars,” Engineering, Technology and Applied Science Research, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 10776–10780, Jun. 2023, https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.5871

-

R. Mavlonov and S. Razzakov, “Numerical modeling of combined reinforcement concrete beam,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 401, p. 03007, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202340103007

-

V. Vimonsatit, A. S. Wahyuni, and H. Nikraz, “Reinforced concrete beams with lightweight concrete infill,” Scientific Research and Essays, Vol. 7, No. 27, pp. 2370–2379, Jul. 2012, https://doi.org/10.5897/sre12.115

-

A. B. Raheem and F. S. Klak, “Shear strength of conventional and lightweight concrete I-beams with fibrous webs,” Engineering, Technology and Applied Science Research, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp. 16486–16491, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.8155

-

S. Razzakov and A. Martazaev, “Mechanical properties of concrete reinforced with basalt fibers,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 401, p. 05003, Jul. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202340105003

-

R. Mavlonov, S. Razzakov, and S. Numanova, “Stress-strain state of combined steel-FRP reinforced concrete beams,” in E3S Web of Conferences, Vol. 452, p. 06022, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202345206022

-

A. Martazaev, M. Orzimatova, and M. Xamdamova, “Determination of optimum quantity of silica fume for high-performance concrete,” in The 3rd International Symposium on Civil, Environmental, and Infrastructure Engineering (ISCEIE) 2024, Vol. 3317, p. 030012, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0266799

-

Pandimani, M. R. Ponnada, and Y. Geddada, “Numerical nonlinear modeling and simulations of high strength reinforced concrete beams using ANSYS,” Journal of Building Pathology and Rehabilitation, Vol. 7, No. 1, p. 22, Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41024-021-00155-w

-

M. S. Manharawy, A. A. Mahmoud, O. O. El-Mahdy, and M. H. El-Diasity, “Experimental and numerical investigation of lightweight foamed reinforced concrete deep beams with steel fibers,” Engineering Structures, Vol. 260, p. 114202, Jun. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.114202

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.