Abstract

A variable-adaptive-law control algorithm for application to common problems like multi-objective control, actuator output constraints, and suboptimal adaptive laws is proposed in this paper. The multi-objective control problem of a nonlinear suspension is converted to the constrained stability problem of a sprung mass using a quarter nonlinear-suspension model. A variable-adaptive-law controller is then used, along with feedback from the output error, and considering the constraints of the actuator output. The controller modifies the adaptive law to reduce the active control force and restores it to the unsaturated zone. This ensures that the suspension system is always in a controlled state when the output saturation occurs. The controller was simulated for the following two cases: (i) a bump road and (ii) a C-grade road. The analysis is verified by experiments in the end.

1. Introduction

The suspension system of a vehicle is a nonlinear time-varying system with uncertainties. The excitation from the road inputs energy into the suspension system. The damper consumes this energy, thereby stabilizing the whole system. In a passive suspension, the adopted value of the damping coefficient is a compromise for a variety of road conditions. In a semi-active suspension, the damping coefficient is adjustable, which enables the suspension to adapt to a variety of paved surfaces [1]. An active suspension is stabilized using an actuator, which can provide the required active force [2].

Magnetorheological damper (MRD) is a damper that uses the magnetorheological fluid (MRF). The shear stresses in the MRF can change with a varying magnetic field [3]. This property can be utilized for adjusting the damping coefficient of the MRD using a varying current that gives rise to a varying magnetic field. MRDs are widely used in semi-active suspensions. There are several studies that have used MRDs quite effectively. Both a magnetorheological damper and an adaptive sliding-mode algorithm were used in a bicycle in [4]. The optimal control force could be computed by tracking the idealized model using a controller designed in [5, 6]. A special MR damper was developed in [7], and the sky-hook algorithm was used to reduce the vibration acceleration of the entire vehicle. An MR damper was also used in a train in [8], and the H-infinity algorithm served to control the vibration. Another study [9] describes a controller that was built to compensate for the uncertainties of the quarter suspension model and MR damper to improve the robustness of the system. Variable damping aperture control is another type of semi-active suspension that has been studied [10]. Active suspensions are more widely studied compared to semi-active suspensions. In [11], a combination of linear-quadratic regulator (LQR) and neural-network controls improve the stability of the camera. Some researchers [12, 13] studied the use of an inertia container as the active output mechanism to reduce the acceleration of the body. Suspension systems that use fuzzy control was used in an electromagnetic suspension system in [14]. A disturbance observer was established based on the sliding-mode controller in [15]and verified by experiments. In [16], grey predictive control and fuzzy controllers were combined. A hybrid control algorithm was also used in [17]. An active electromagnetic suspension with good control effect in the high frequency range was designed and verified in [18], while [19] used a data-driven method to adjust a fixed order controller. Active suspension systems have also been controlled using a linear feedback controller designed especially for nonlinear systems [20] and an LQR controller combined with a risk-sensitive controller [21]. In the literature mentioned above, regardless of the nature of the damper, whether MRD, inertia or electromagnetic actuator, the main objective was to reduce the sprung-mass acceleration, and this objective was achieved to a considerable degree as verified by experiments in several cases. However, safety and the suspension travel limit should also be considered along with the increase in ride comfort. In other words, it is not enough to reduce the sprung-mass acceleration alone, and active suspension control should be treated as a multi-objective control problem.

According to [22, 23], multi-objective control of the suspension can be approximated as a control problem in which minimization of the sprung-mass acceleration is the primary objective, while the dynamic tire load and suspension space limit are the constraints. Multi-objective control was realized by assigning different weights for the sprung-mass acceleration, space requirements of the suspension, and dynamic tire load [24, 25]. Additionally, in real-world applications, the output force of the actuator is limited, presenting a new problem: the output force of the actuator acts as a constraint on the system [26]. To model this, an actuator saturation-control problem was formulated and solved [27, 28]. Active fault tolerance control was studied in [29-31] and the uncertainties in output were taken into consideration [32]. A significant number of adaptive-control algorithms were designed to make the controlled suspensions more stable. However, there is still no satisfactory solution to the problem of finding an ideal adaptive law, which is typically chosen based on experience. In addition, there is usually no connection between the adaptive law and the output constraints on a system. Hence, there is need for further improvement of suspension control systems.

2. Governing equation for a controlled suspension

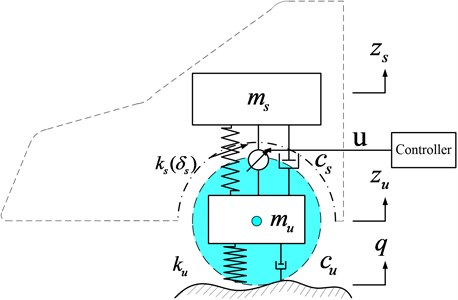

As shown in Fig. 1, the body mass of the car and the passenger mass are taken together as the sprung mass , which varies with the load over a small range. The mass of the wheel, brake system, and other connections are lumped together as the unsprung mass . The sprung and unsprung masses are connected by a spring and a damper . The spring in the model is a combination of a linear spring and a nonlinear spring . The unsprung mass is supported on the ground by an equivalent linear spring and a linear damper . In an active suspension, the actuator generates an active force, whose function is to improve the ride comfort.

Fig. 1A nonlinear quarter car-suspension with an active controller

According to Newton’s second law, the governing equations are:

where:

which are the restoring forces at the corresponding dampers and springs.

We define the state variables , , , , and Eq. (1) can be modified as:

where represents the saturation function of the output force. is a variable parameter, which changes with the load and satisfies the equation:

In addition, since the actual actuator output has the maximum value, the active control-force saturation function is defined as:

Vehicle suspension control can be expressed as a multi-objective control problem, whose objective is the maximization of ride comfort while ensuring the safety of the vehicle and keeping within the limited space available for the suspension system. These conditions can be expressed as:

where is the minimum sprung mass. is the maximum space available for the suspension, and is a finite time.

2.1. Controller design with an ideal actuator

We define the tracking error as where is the reference signal. It is continuous and differentiable and satisfies the condition , where is a positive constant. In the differential form:

The ideal function of the virtual control input is and we define the error:

Substituting Eq. (7) into (6) yields the following equation:

We use the Lyapunov candidate function:

Differentiating yields the following equation:

We then choose an ideal function:

where is a positive constant. Substituting Eq. (11) into (10) yields:

From Eq. (12) we can see that, if , then , ensuring that converges to zero.

Differentiating Eq. (7) yields the following equation:

We define the term:

where is an estimate of . The Lyapunov candidate function now considered is:

where is a positive constant. Differentiating Eq. (15) yields:

We choose:

and substitute Eq. (17) into Eq. (16) to yield the following equation:

We then define the adaptive law as follows:

Eq. (19) implies that when the rate of variation of the adaptive law rate is positive, it eventually reaches the maximum and when the rate of variation in the adaptive law is negative, the value eventually reaches the minimum. When the rate of variation of the adaptive law is set to zero, i.e., there is no variation, the value remains stable within a range.

Substituting Eq. (19) into (18) yields:

Integrating Eq. (20) yields the following:

From Eqs. (20) and (21), we can see that , , and are finite, and , as .

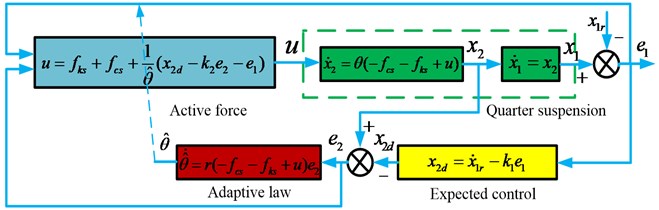

The structure of the controller is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2Schematic diagram of an adaptive controller

2.2. Controller design with an actuator having output constraints

In reality, the output of the actuator has the maximum value. Therefore, when the active control force exceeds the maximum value, the actuator cannot track it further. In this situation, the error should be compensated:

where is a positive constant, is the initial value of the uncertain parameter , and represents the difference in the output. Substituting Eq. (22a) into Eq. (6) yields the following equation:

Substituting Eq. (23) into Eq. (10) yields:

We choose the ideal function:

Substituting Eq. (25) into Eq. (24) yields:

From Eq. (26) we can see that, if , then , ensuring that converges to zero.

The active control force is given in Eq. (17). When output saturation occurs, the variable adaptive law stated below is used:

where is a positive constant. This particular form of the variable adaptive law, shown in Eq. (27), is chosen because:

(a) When output saturation occurs, the variation in the adaptive law is increased to reduce the active control force and restore it to the unsaturated region. This ensures that the suspension system is always in a controlled state.

(b) When output saturation occurs, is modified by changing the adaptive law.

We consider a Lyapunov candidate function:

Here, the set is a compact set for any :

In a compact set , has the maximum value. In addition, the following can be obtained according to the properties of a perfect square:

Differentiating Eq. (28), we get:

where, . From Eq. (31) we can see that if the following condition:

is satisfied, we obtain:

The following equation can then be obtained from Eq. (33):

where is the exponential index. From Eq. (34) we can see that , , are finite when .

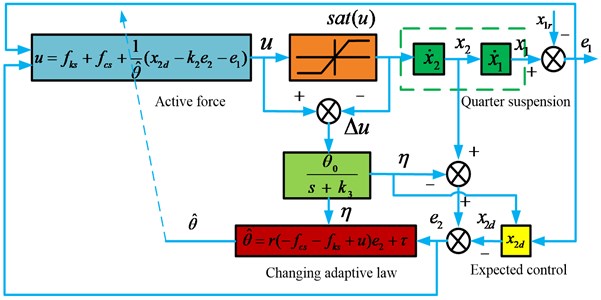

The mathematical model of the controller with output constraints is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3Schematic diagram of adaptive controller with output constraints

The zero dynamic stability of the system can be proved using the following equations. When , , which indicates that the output does not reach the constraint (), we obtain:

After replacing in Eq. (2d) with that in Eq. (35), the zero-dynamic system obtained can be represented as:

where:

Since matrix is a Hurwitz matrix, the zero-dynamic system is stable.

3. Numerical simulation

The quarter suspension model parameters are shown in Table 1.

The controller parameters are shown in Table 2.

Table 1Quarter suspension model parameters

Parameters | |||||||

Unit | kg | kg | N/m | N/m | N/m | Ns/m | Ns/m |

Value | 324 | 45 | 20000 | 2000 | 180000 | 1000 | 500 |

Table 2Controller parameters

Parameters | ||||||||||

Value | 0.01 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 1/300 | 1/350 | 1/300 | 0.5 | 1250 | 700 |

Simulations were carried out for the following three states:

(a) Variable-adaptive-law controller with output constraint,

(b) Fixed-adaptive-law controller with output constraint,

(c) Passive states.

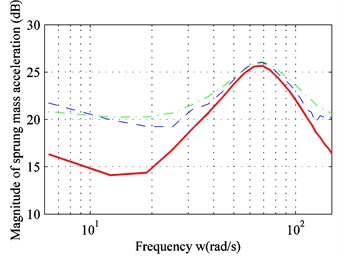

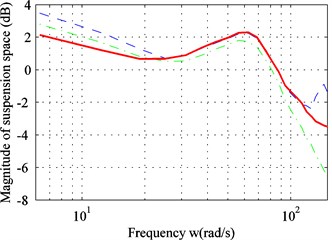

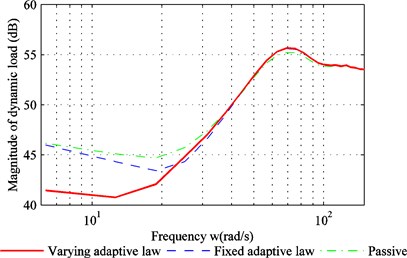

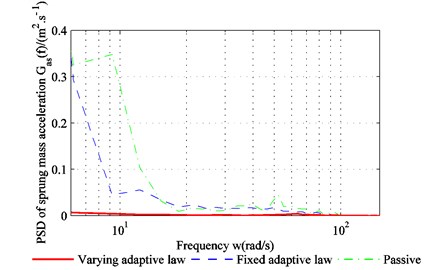

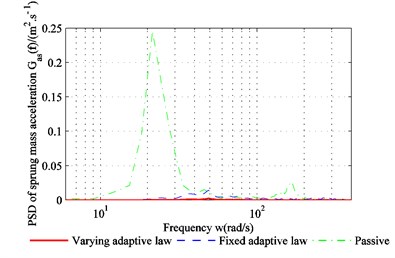

3.1. Frequency response

As shown in Fig. (4a), due to the output constraint of the actuator, the sprung-mass acceleration of the nonlinear suspension with a fixed-adaptive-law controller does not differ much from that of a passive suspension. However, it has a slightly smaller value than the sprung mass acceleration of the passive suspension. In other words, given the output constraint, the equilibrium state of the adaptive-control system is destroyed, and the controller performance degrades. However, the sprung-mass acceleration of the nonlinear suspension with a variable-adaptive-law controller is much smaller than the passive one, and the controller performance is very good thereby validating its efficiency. As can be seen from Fig. (4b), the dynamic stroke of the active suspension is increased at an excitation frequency greater than 25 rad/s, which ensures good controller performance. The effect on the dynamic load of the tire is small and becomes progressively smaller for lower frequencies.

Fig. 4Frequency response of: a) sprung mass acceleration; b) suspension space; c) dynamic load of the tire

a)

b)

c)

3.2. Time-domain analysis

The simulation is carried out for a bump road and C level road. The bump-road surface is generated according to the following function:

3.2.1. Comparison with a bump road

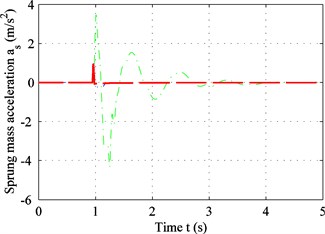

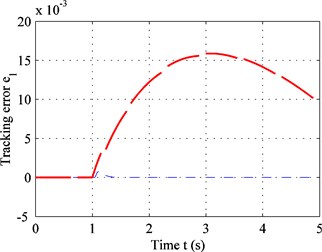

Fig. 5 shows the response of the suspension to a bump road. The bump road can be treated as a case of transient unbalanced excitation, which can reflect the performance of a controller with an asymmetrical output constraint. In Fig. (5a), the sprung-mass acceleration of the active suspension with a variable-adaptive-law controller drops to zero rapidly after a slight increase. It then remains stable. For the fixed-adaptive-law controller, it will continue to increase in the reverse direction, and then gradually decrease to zero. This shows the superiority of the variable-adaptive-law controller. To maintain the small sprung-mass acceleration for as long as possible, the output force with avariable-adaptive-law controller decreases to zero for longer periods. This results in a longer time to stabilize for tracking error and suspension travel – see Figs. (5b), (5c) and (5d). In Fig. (5e), the dynamic load of the tire increased significantly after a sudden impact, but these temporary changes do not affect vehicle safety.

Fig. 5Performance comparison with a bump road: a) sprung mass acceleration; b) tracking error; c) output force; d) suspension space; e) dynamic load of tire

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

3.2.2. Comparison with the C-level road

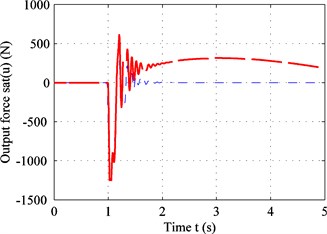

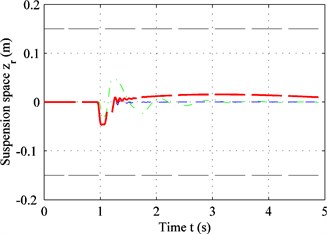

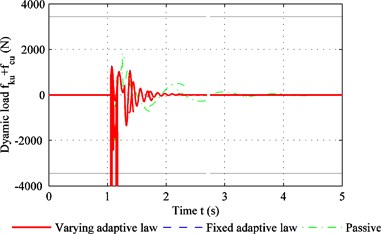

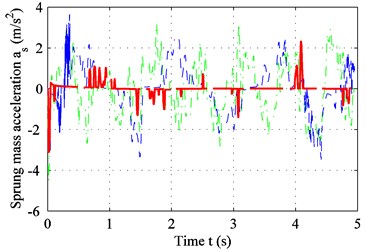

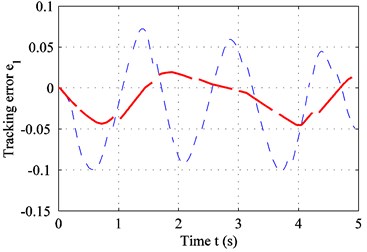

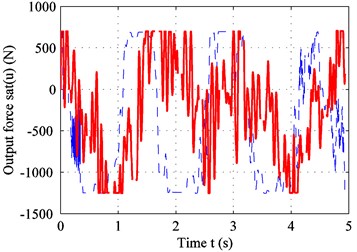

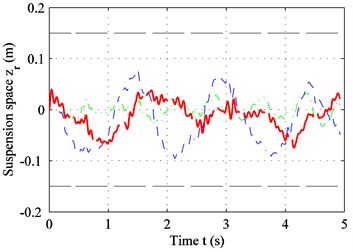

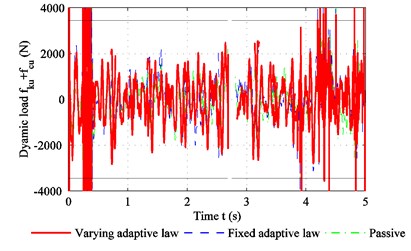

Fig. 6 shows the response of the suspension for a C-level road when the vehicle speed is 20 m/s. As shown in Fig. 6, for a random road, when the calculated active force is less than the actuator output constraint, the performance of the variable-adaptive-law controller is identical to the fixed adaptive-law controller, and the sprung mass acceleration is zero. When the driving force exceeds the actuator output constraint, the system balance is disturbed. Until this point, the variable-adaptive-law controller is superior to the fixed adaptive-law controller with a smaller sprung-mass acceleration (Fig. (6a)), smaller tracking error (Fig. (6b)), and smaller suspension travel (Fig. (6d)). However, it can be seen from Fig. (6e) that the controller cannot reduce the dynamic tire load when the output is constrained. In cases where the road excitation is very strong, even the controller with no output constraints imposed on the system approaches its limit. If the output control force is restricted at this moment, the control effect on dynamic tire load will also necessarily be reduced.

Fig. 6Performance comparison with the C-level road: a) sprung mass acceleration; b) tracking error; c) output force; d) suspension space; e) dynamic load of tire

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

Fig. 7 shows that, for the low-frequency range, the sprung-mass acceleration of the active suspension is smaller than the passive suspension. However, when the frequency is greater than 15 rad/s, the effectiveness of the fixed-adaptive-law controller decreases significantly because of the output constraint on the actuator. The sprung-mass acceleration with this controller is only slightly less than that for the passive suspension. However, the performance of the variable-adaptive-law controller is still acceptable.

The root-mean-square values of the sprung-mass acceleration for two kinds of road surfaces are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 7PSD (power spectral density) of sprung-mass acceleration in frequency domain

Table 3The root-mean-square value for sprung-mass acceleration

Road type | Bump road | C-grade road |

Passive (m/s2) | 1.4018 | 1.5897 |

Variable adaptive law (m/s2) | 0.2603 | 0.3163 |

Fixed adaptive law (m/s2) | 0.2739 | 1.4861 |

It can be seen from Table 3 that the reduction in the sprung-mass acceleration is best with the variable-adaptive-law controller. Compared to the passive suspension, the sprung-mass acceleration decreased by 81.43 %, 80.46 %, and 80.19 %, 6.52 %, respectively for both kinds of roads.

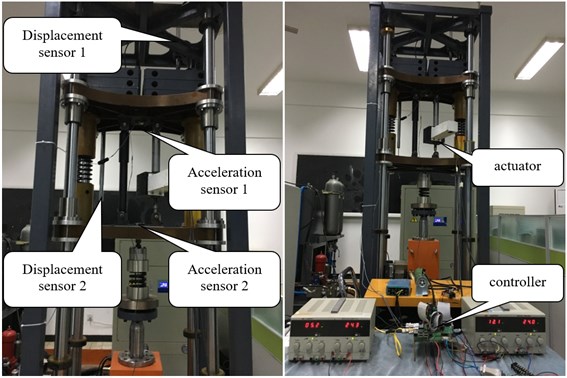

4. Experimental verification

The experiment detailed in this section was carried out to verify the effectiveness of the designed controller. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 8. The actuator used in the experiment consists of a rotating motor, a rack, and a pinion.

The base excitation is generated by the hydraulic cylinder. Positioned between the hydraulic cylinder and the unsprung mass is a spring that approximates a tire. The sprung mass and the unsprung mass are connected by a damper and an actuator. The controller considered in this study operates on an embedded system.

Four sensors are used in the test to convert the analog data pertaining to physical quantities into electrical signals. The displacement sensor 1 (TWZ, 500 mm) is fixed on the test equipment with its movable rod fixed on the upper desk. It collects data regarding the displacement of the sprung mass. The acceleration sensor 1 (CS-LAS-02, ±10 g) is fixed at the center of the upper desk and measures the acceleration of the sprung mass. The displacement sensor 2 (TWZ, 250 mm) is fixed to the upper desk with its movable rod attached to the bottom desk in order to measure the displacement between the sprung and unsprung masses. Acceleration sensor 2 (CS-LAS-02, ±10 g) is attached to the center of the bottom desk and measures acceleration of the unsprung mass. DC power supply is provided for all four sensors. A data acquisition module installed on an embedded controller is responsible for collecting the signals from the four sensors. The velocity values can be obtained by differentiating the measured displacements from the sensor, and these comprise the inputs to the control system. With the data so-obtained, the proposed algorithm can run on the embedded controller. The resulting data, which is the output of the control system, is used to control an actuator attached between the upper and lower desks.

During the experiment, the physical quantities are measured by the sensors and transferred to the controller. The controller generates a corresponding signal which is supplied to the actuator. The actuator generates the active force. Thus, the experiment simulates the real-life active control of the suspension system.

Fig. 8Experimental setup

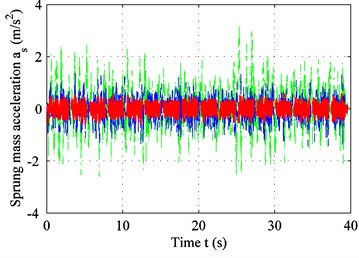

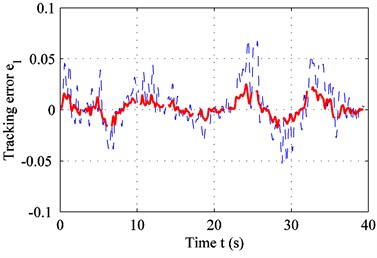

Fig. 9Experimental results for: a) sprung-mass acceleration; b) tracking error; c) PSD of sprung-mass acceleration

a)

b)

c)

Fig. 9 shows the experimental results for the C-level road. The parameters are the same as those in Table 1 and Table 2. From Fig. (9a) and (9c), it can be seen that the sprung-mass acceleration for the variable-adaptive-law controller is smaller, and the plots of the tracking error shown in Fig. (9b) confirm this. In practice, the actuator always fluctuates between the maximum limits, when it reaches the constraints because it can maintain only a constant value in a simulated state. This means that it cannot switch instantly, which explains the variation between the experiment and the results of the theoretical analysis. In addition, the time delay and inaccurate estimate of platform parameters affect the result. However, in general, the variable adaptive law controller is superior to the fixed adaptive law controller.

5. Conclusions

A variable-adaptive-law control algorithm was studied for application to problems like multi-objective control, actuator output constraints, and suboptimal adaptive-law choices. With an ideal actuator, the conventional adaptive control algorithm works well. However, when the output constraints of the actuator are taken into consideration, the conventional adaptive-control algorithm no longer performs satisfactorily. This problem is solved in the proposed controller by adjusting the adaptive law. From the experiment result, we can conclude that:

1) Control over the system can be maintained under all conditions. With a variable-adaptive-law controller, the output constraints can be met. This is critical in actual engineering applications.

2) Better riding comfort can be achieved with the variable-adaptive-law controller compared with a fixed adaptive-law controller when output constraints are met. Smaller sprung-mass accelerations and tracking errors are observed in both the simulation and experiment, confirming the outstanding performance of this controller.

3) The controller can be modified according to specific requirements. It has been proved that the controller is stable with changes like variations in the adaptive law. This means that any adaptive controller has the potential to be a better one in some extreme environment like output saturation. This is a significant improvement in the active control of suspension systems.

References

-

Majdoub K. E., Ghani D., Giri F., Chaoui F. Z. Adaptive semi-active suspension of quarter-vehicle with magnetorheological damper. Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, Vol. 137, 2015, p. 021010.

-

Rath J. J., Vekuvolu K. C., Defoort M. Active control of nonlinear suspension system using modified adaptive supertwisting controller. Discrete Dynamic in Nature and Society, 2015, p. 408623.

-

Zhao M., Zhang J., Yao J., Peng Z. Effects of nano diamond on magnetorheological fluid properties. NANO, Vol. 12, Issue 10, 2017, p. 1750119.

-

Yeh F. K., Chen Y. Y. Semi-active bicycle suspension fork using adaptive sliding mode control. Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 19, Issue 6, 2012, p. 834-846.

-

Khiavi A. M., Mirzaei M., Hajimohammadi S. A new optimal control law for the semi-active suspension system considering the nonlinear magneto-rheological damper model. Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 20, Issue 14, 2014, p. 2221-2233.

-

Yao J.-L., Shi W.-K., Zheng J.-Q., Zhou H.-P. Development of a sliding mode controller for semi-active vehicle suspensions. Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 19, Issue 8, 2012, p. 1152-1160.

-

Ha S. H., Seong M. S., Choi S. B. Design and vibration control of military vehicle suspension system using magnetorheological damper and disc spring. Smart Materials and Structures, Vol. 22, 2013, p. 065006.

-

Shin Y. J., You W. H., Hur H. M., Park J. H. H∞ control of railway vehicle suspension with MR damper using scaled roller rig. Smart Materials and Structures, Vol. 23, 2014, p. 095023.

-

Yıldız A. S., Sivrioglu S., Zergeroglu E., Cetin S. Nonlinear adaptive control of semi-active MR damper suspension with uncertainties in model parameters. Nonlinear Dynamics, Vol. 79, 2015, p. 2753-2766.

-

Chen H., Long C., Yuan C. C., Jiang H. B. Non-linear modelling and control of semi active suspensions with variable damping. International Journal of Vehicle Mechanics and Mobility, Vol. 51, Issue 10, 2013, p. 1568-1587.

-

Zhao F., Dong M., Qin Y., Gu L., Guan J. Adaptive neural networks control for camera stabilization with active suspension system. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 7, Issue 8, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1177/1687814015599926.

-

Li P., Lam J., Cheung K. C. Control of vehicle suspension using an adaptive inerter. Journal of Automobile Engineering, Vol. 229, Issue 14, 2015, p. 1934-1943.

-

Zilletti M. Feedback control unit with an inerter proof-mass electrodynamic actuator. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 369, 2016, p. 16-28.

-

Su X., Yang X., Shi P., Wu L. Fuzzy control of nonlinear electromagnetic suspension systems. Mechatronics, Vol. 24, 2014, p. 328-335.

-

Deshpande V. S., Mohan B., Shendge P. D., Phadke S. B. Disturbance observer based sliding mode control of active suspension systems. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 333, 2014, p. 2281-2296.

-

Lin J., Lian R.-J. Design of a grey-prediction self-organizing fuzzy controller for active suspension systems. Applied Soft Computing, Vol. 13, 2013, p. 4162-4173.

-

Montazeri Gh M., Kavianipour O. Investigation of the active electromagnetic suspension system considering hybrid control strategy. Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, Vol. 228, Issue 10, 2014, p. 1658-1669.

-

Sande T. P. J. V. D., Gysen B. L. J., Besselink I. J. M., Paulides J. J. H., Lomonova E. A., Nijmeijer H. Robust control of an electromagnetic active suspension system: simulations and measurement. Mechatronics, Vol. 23, 2013, p. 204-212.

-

Formentin S., Karimi A. A Data-driven approach to mixed-sensitivity control with application to an active suspension system. Industrial Informatics, Vol. 9, Issue 4, 2013, p. 2293-2300.

-

Xiao Z. L., Jing X. Frequency-Domain analysis and design of linear feedback of nonlinear systems and applications in vehicle suspensions. Mechatronics, Vol. 21, Issue 1, 2016, p. 506-517.

-

Brezas P., Smith M. C. Linear quadratic optimal and risk-sensitive control for vehicle active suspensions. Control Systems Technology, Vol. 22, Issue 2, 2014, p. 543-555.

-

Sun W., Pan H., Gao H. Multi-objective control for uncertain nonlinear active suspension systems. Mechatronics, Vol. 24, 2014, p. 318-327.

-

Huang Y., Na J., Wu X., Liu X., Guo Y. Adaptive control of nonlinear uncertain active suspension systems with prescribed performance. ISA Transactions, Vol. 54, 2015, p. 145-155.

-

Zuo L., Zhang P.-S. Energy harvesting, ride comfort, and road handling of regenerative vehicle suspensions. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 135, 2013, p. 011002.

-

Türkay S., Akçay H. Multi objective control of a full car model using linear matrix inequalities and fixed order optimisation. International Journal of Vehicle Mechanics and Mobility, Vol. 52, Issue 3, 2014, p. 429-448.

-

Li P., Lam J., Cheung K. C. Multi-objective control for active vehicle suspension with wheelbase preview. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 333, 2014, p. 5269-5282.

-

Gu Z., Fei S., Zhao Y., Tian E. Robust control of automotive active seat-suspension system subject to actuator saturation. Journal of Dynamic Systems, Measurement, and Control, Vol. 136, 2014, p. 041022.

-

Pan H., Sun W., Gao H., Jing X. Disturbance observer-based adaptive tracking control with actuator saturation and its application. Automation Science and Engineering, Vol. 13, Issue 2, 2016, p. 868-875.

-

Moradi M., Fekih A. Adaptive PID-sliding-mode fault-tolerant control approach for vehicle suspension systems subject to actuator faults. Vehicular Technology, Vol. 63, Issue 3, 2014, p. 1041-1054.

-

Yao J., Zhang J., Zhao M., Peng H. Analysis of dynamic stability of nonlinear suspension concerning slowly varying sprung mass. Shock and Vibration, Vol. 2017, 2017, p. 5341929.

-

Sun Y., Qiang H., Mei X., Teng Y. Modified repetitive learning control with unidirectional control input for uncertain nonlinear systems. Neural Computing and Applications, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-017-2983-y.

-

Li H., Liu H., Hilton C., Hand S. Non-fragile H control for half-vehicle active suspension systems with actuator uncertainties. Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 19, Issue 4, 2012, p. 560-575.

About this article

This project did not receive any specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.