Abstract

In this paper, the detailed study of the transversal vibrations of a damped axially moving string is considered. Two end pulleys of the string are taken to be fixed and the initial conditions are assumed to be of general displacement field and the general velocity field. The axial speed of the string is considered to be sinusoidal, time-dependent and small compared to wave-velocity. A two timescales perturbation method with a combination of Fourier-sine series which fits the boundary conditions is employed in order to formulate the valid and uniform asymptotic approximations of the exact solutions for the equation. It is found that there are infinitely many values of frequency parameter which cause the internal resonances in system. The fundamental resonant frequency, the non-resonant frequency and the detuning cases have been discussed and analyzed in detail. It has been found explicitly that the total mechanical energy of the infinite dimensional system decreases for two cases of the damping parameter, that is, for and for . By truncation method it has been shown that the mode-amplitude response for first few modes is stable. So, Galerkin’s truncation method may be possible for these two cases of the parameter . But for case the total mechanical energy of belt system is increasing exponentially. Therefore, it is evident that the Galerkin’s truncation method cannot be applied in order to obtain valid approximations on long timescales, that is, on timescales of .

1. Introduction

There are numerous applications in engineering such as elevators [1-5], aerial cables, crane and mining hoists, conveyor belts [6-9], oil pipelines [10, 11], magnetic and paper tapes and band-saw blades [12], are often known as axially moving systems. Since last few decades, there has been vast research activity on examining the stability of such systems, for instance, see [13-19]. Irregular speed of driven motor, non-uniform material properties and environmental disturbances can lead to severe vibrations, which are not desirable phenomena. Such severe vibrations can discomfort human beings and sometimes may create great damage to these mechanical structures. The main goal of applied mathematicians, engineers and physicists is to understand, analyze and mitigate these vibrations from the mechanical systems. In order to reduce unnecessary noise and vibrations in these mechanical systems, researchers have used different kinds of dampers at different positions of these systems, such as internal dampers [20], external dampers [21], wire rope [22, 23], elastomeric bearing [24] and Kelvin-Voigt damping [25] are extensively used in practical and industrial applications. Darmawijoyo and van Horssen [26] considered wave equation and studied the behaviour of spring-mass-dashpot system attached at one boundary by using perturbation method. In this paper it was shown that the boundary damping is an effective phenomenon to suppress amplitudes of oscillations. Sandilo and van Horssen [27] studied beam-like equation with non-classical boundary condition at one end and simply support on other end. In this paper though authors did not find any conclusion whether beam energy was increasing or decreasing, but authors found very interesting results. Gaiko and van Horssen [28] employed two timescales perturbation method and obtained the asymptotic approximations for (lateral) oscillations in axially moving string under the effect of boundary damping. Darmawijoyo and van Horssen [29] used two timescales perturbation method for finding the solution of weakly nonlinear wave equation with non-classical boundary conditions. Darmawijoyo et al. [30] studied weakly nonlinear string equation, where one end of string was kept fixed and to the other end a dashpot was attached. A two timescales perturbation method with combination of method of characteristics was employed and it was shown that for large damping parameter solutions tend to zero. Chen and Ferguson [31] studied the axially moving viscoelastic string under viscous damping and, constant and time-varying length. The linear and nonlinear models were discussed from numerical solutions point of view. Malookani et al. [32] studied an axially moving string where they considered spring-dashpot system at one end and other end was kept fixed. Asymptotic approximations of the exact solutions were obtained by using a two timescales perturbation method with method of characteristic coordinates. Malookani and van Horssen [33] examined the lateral vibrations of axially moving system and computed the amplitude-response of the system for all modes. The authors used method of two timescales together the Laplace transform method.

This paper aims to examine the applicability of Galerkin’s truncation method for the model describing the transversal vibrations of axially moving string under the influence of viscous damping, with time-varying velocity.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the governing equations of motion are established. In Section 3, the asymptotic approximations of the exact solution of the initial-boundary value problem are constructed by using a two timescales perturbation method. These solutions will be analyzed and a Galerkin’s truncation method will be applied in order to truncate few modes from the infinite dimensional system of ODE’s. The detuning and the non-resonant cases will also be discussed in detail. In Section 4, the results and the discussion are presented. Finally, in Section 5, some conclusions will be drawn and the remarks will be made.

2. Governing equations of motion

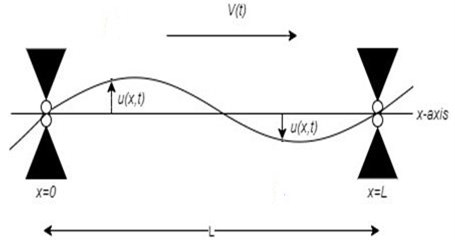

In this Section, we consider viscous damped axially translating string, moving with time-varying velocity as shown in Fig. 1. It is assumed that the displacement field is zero at end points of string, i.e., at and, where is the constant distance between the pair of pulleys. The mathematical formulation of a string with viscous damping is carried out by extended Hamilton’s principle [34]. The mathematical formulation of the model describing the vertical vibrations of string with viscous damping is given as under:

with the Dirichlet boundary conditions:

and the initial conditions:

where is the time, is the spatial coordinate, is the vertical displacement field, is the belt velocity, is the linear constant mass-density, is the constant tension, and is viscous damping coefficient. At 0, the displacement and velocity of the string are represented by the functions and, respectively. In order to convert the equation of motion with associated initial-boundary conditions in non-dimensional form, we use the following non-dimensional parameters:

where , is a wave speed. Substitution of Eq. (4) and all required derivatives of unknown function into initial-boundary value problem Eqs. (1)-(3) give the following dimensionless form of equations of motion (where asterisks have been neglected):

It is assumed that the quantity is small in comparison to , where. Thus, we can write, where is small dimensionless parameter with . In addition to this, it is also assumed that the axial speed is time-varying and small in comparison to wave-speed Thus, we can write , where and are constants with and ; this condition guarantees that the belt will always move in one direction. The velocity fluctuation frequency of belt is denoted by . The sinusoidal form of the belt velocity is of practical usage. In reality, however, due to belt imperfections, roll eccentricities, speed variations in driven motors, and non-uniform material properties can cause small variations in the belt velocity. This variation in the belt velocity exhibits interesting mathematical complexities and dynamical features.

Fig. 1The schematic model of a damped axially moving belt with two fixed-ends

3. Construction of asymptotic approximations

In this section, we shall construct the asymptotic approximations of the solutions of the initial-boundary value problem Eqs. (5)-(7). We assume that the string velocity is time-varying and is of the , as given below:

We also assume that the damping parameter is of the , as given by:

By plugging Eq. (8) and Eq. (9) into Eq. (5), we collect the terms up to , we get:

with the boundary conditions:

and the initial conditions:

In order to construct the asymptotic approximations of the solution of the initial-boundary value problem Eqs. (10)-(12), we expand in Fourier-sine series, given as under:

The orthogonality properties of the eigenfunctions are given by:

By making use of Eq. (13) with required time and space derivatives into Eq. (10), it follows:

By multiplying Eq. (16) with on both sides and then by integrating the so-obtained equation from 0 to 1, and by using Eq. (14) and Eq. (15), it yields:

Eq. (17) represents an infinite dimensional system of ODE’s, which is not easy to be solved exactly. In the subsequent Section, the application of a two timescales perturbation method will be carried out to obtain approximations of the solutions of Eq. (17) for different values of the parameter .

3.1. A two timescales perturbation method

In this section, we discuss the application of a two timescales perturbation method for constructing the approximations of the solutions of the infinite dimensional system of ODE’s given in Eq. (17). A straightforward expansion in will lead to unbounded terms which cause the non-uniformity in the solutions and this method is only applicable for . Therefore, to approximate the exact solutions valid on long timescales, that is a timescales of , it is reasonable to use a two timescales perturbation method. We introduce two timescales, (fast timescale) and (slow timescale). We assume that the solution of Eq. (17) in the form . The following transformations are required to express the time derivatives:

We plug Eq. (18) and Eq. (19) into Eq. (17), it follows:

An approximation of is sought in the following form (up to and neglecting higher order terms):

where , ,… are of . By substituting Eq. (21) into Eq. (20), and equating the coefficients of and , the - and the -problem for and are given.

The problem:

The problem:

The solution of Eq. (22) can easily be obtained, and is given by:

where and are still arbitrary functions of slow timescales and they can be determined from the -problem free from the secular terms. Since we have assumed that the functions and are bounded on timescales of so these unbounded/secular terms must be prevented to have valid and uniform approximations on long timescales. From Eq. (23), it turns out that the resonances only occur if, , or when is odd.

3.2. The fundamental resonance case

This section discusses the fundamental resonant frequency case, that is, the frequency of the moving string is equal to fundamental natural frequency of the string, that is . After putting into the -problem given in Eq. (23) and by avoiding the secular terms in ; the functions and have to satisfy the following solvability conditions:

where , and . The functions and are defined to be zero for non-positive indices. For sake of suitability, the bar from and is omitted. The coupled system Eq. (25) is an infinite dimensional system of ODE’s. It is evident from system Eq. (25) that there are infinitely many interfaces between the vibration modes. For in Eq. (25) is referred to [6].

3.2.1. Mathematical analysis of infinite dimensional system (25)

This subsection computes the energy of the axially moving system from coupled system given in Eq. (25) by using following transformations.

Let and , then Eq. (25) becomes:

where and the functions and are zero for non-positive indices By multiplying and with first and second equations in Eq. (26) respectively, we get:

By addition both equations in system Eq. (27), and by taking the sum from to , it yields:

By differentiating Eq. (28) with respect ,it yields:

and then by putting into Eq. (29) yields:

The solution of Eq. (30) is:

where and are constants and can be computed by applying the given initial conditions. Now by multiplying Eq. (5) with and after long but elementary calculations we get:

Integrate Eq. (32) first with respect to over the interval , and then with respect to over ] it yields:

Thus, the total mechanical energy of the string under viscous damping is given by:

The energy of the axially moving string can also be computed by using the energy function . Using Eq. (24) into Eq. (13) the approximated solution up to is given by:

Thus, approximate energy of belt system can be obtained by plugging Eq. (35) into Eq. (34) it becomes:

On further simplification, it yields:

This implies that:

As , and using Eq. (31), so Eq. (37) becomes:

The following cases arise for damping parameter

– Case I: For the energy of system decreases in the smaller domain of time and then remains constant.

– Case II: For the energy decays as time increases.

– Case III: For the energy increases without bound as time grows.

– Case IV: For 0, then the system exhibits the similar behaviour as shown in [6].

3.2.2. Galerkin’s truncation method

This subsection investigates the application of truncation method for the system Eq. (25). The truncation up to three modes is given below:

where:

This linear system has the eigenvalues , , all with multiplicity of and their associated eigenvectors are given as follows: respectively. Thus, the general solutions of a linear system Eq. (40) is given by:

where , ,…, are all constants and are to be determined via initial conditions: , , , it follows that:

Moreover, since and it follows that:

Thus, by using Eq. (24) and Eq. (45) finally we get:

Now the constants in Eq. (42) can easily be determined by utilizing Eq. (46). Thus for , and we find first three approximate modes as under:

Eq. (47) shows that first three modes are clearly damped out and amplitude of oscillations gets reduced. It is, however, difficult to calculate four and more than four eigenvalues and corresponding eigenvectors manually so we use computer software package Mapple16, to obtain the eigenvalues of coupled system up to modes and are given listed in Table 1. All of these eigenvalues are multiplicity of 2 and the real parts of eigenvalues have negative sign which shows that system is stable in nature. Further for system has same eigenvalues as given in [6].

Table 1The eigenvalues of truncated system Eq. (25)

No. of modes | The Eigenvalues of matrix (All multiplicity of 2) | Dimension of |

1 | 2 | |

2 | 4 | |

3 | 6 | |

4 | 8 | |

5 | 10 | |

6 | 12 | |

7 | 14 |

3.3. The detuning case:

This section presents the (in) stability of the damped axially moving string close to the resonances, i.e.,, where the constant is taken to be positive odd integer. Thus, we demonstrate the closeness of velocity fluctuation by using the relation:

where the parameter is a detuning parameter and is a small dimensionless parameter, that is, . Putting Eq. (48) into Eq. (23) gives for the for:

To avoid the unbounded terms in Eq. (49), the functions and have to satisfy the following solvability conditions:

where and the functions and are defined to be zero for . It can be observed that for and we get same system given in Eq. (25) and for in above coupled system we get same system as given in [33].

3.3.1. Mathematical analysis of infinite dimensional system Eq. (50)

In this subsection we analyze the coupled system of ODE’s for 1, and obtain the energy of the system to examine its behaviour for detuning case. For 1, Eq. (50) reduces as:

where and and 1, 2, 3…. For convenience, we drop the bar from and . By introducing and , where 1, 2, 3…, the system Eq. (51) becomes:

The functions and are zero for . By multiplying the functions and , respectively, the first and the second equations of Eq. (52), it yields:

By adding both sides of Eq. (53), and then by taking the sum from to , it becomes:

After differentiating Eq. (54) twice with respect to , we obtain:

where , thus the roots of auxiliary Eq. (55) are , .

Three cases arise:

Case I: When , that is, then where and are arbitrary constants. In this case, if the energy of system decays as time increases without bound and in this case the system is stable, whereas if then energy grows polynomially; so the energy of infinite dimensional system remains unbounded.

Case II: When that is, then:

and if the energy of system decays as time increases and system is stable. For the energy of infinite system of coupled ODE’s grow exponentially, that is sign for unstable system.

Case III: When that is,, then:

In this case, the energy remains to be bounded.

3.4. The non-resonant case

In this case we assume that the fluctuation frequency in not within an neighbourhood of the frequencies that cause the internal resonance, that is not within an neighbourhood of , then we may have following equation after eliminating the secular terms:

The solution of Eq. (56) is and where and are arbitrary constants. By inserting the solution of Eq. (56) into Eq. (35), we obtain:

Eq. (57) clearly shows that the system damps out due to the presence of damping in the system. The energy of damped string system for non-resonant case can also be approximated by putting Eq. (57) to Eq. (34) it yields:

It can easily be observed from Eq. (58) that energy of damped axially moving string seems stable for non-resonant case.

4. Results and discussion

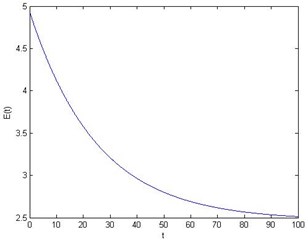

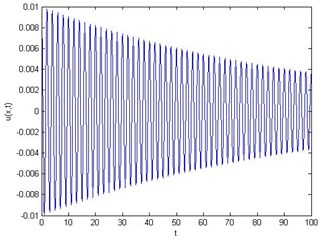

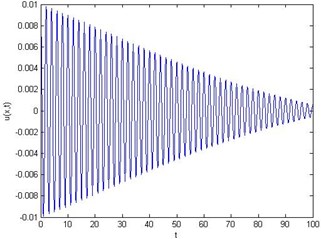

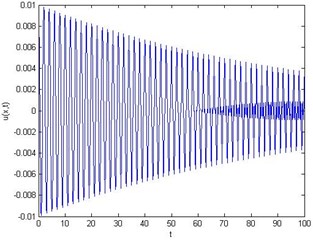

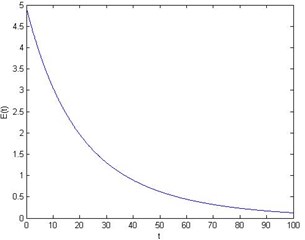

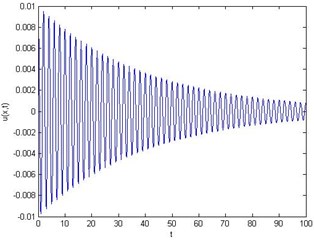

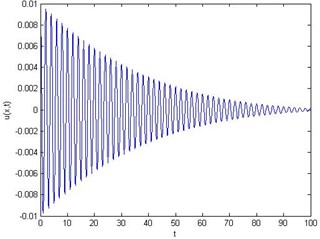

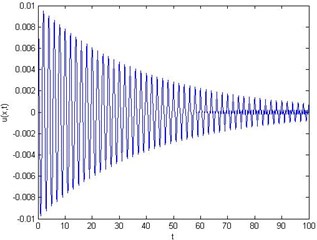

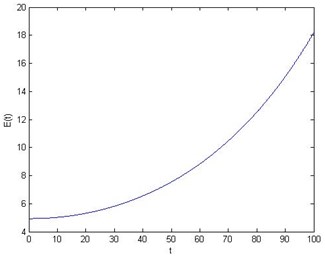

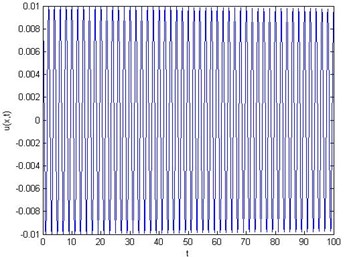

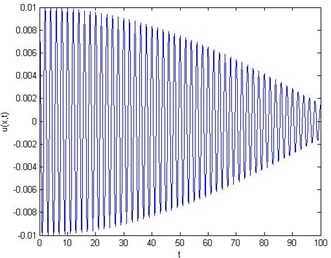

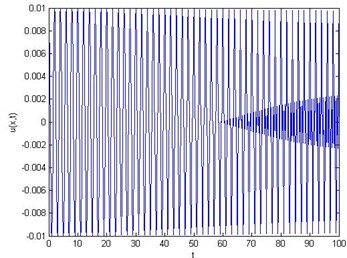

This section presents the results for the transverse vibrations of the damped axially moving string for the resonant, non-resonant cases. It is assumed that the string moves in one direction with time-dependent velocity , where and , , are positive constants. A two timescales perturbation method with conjunction of Fourier-sine series has been employed in search of infinite mode approximate solutions. It has been found that there are infinitely many values of which give rises to the resonances in system. This study, however, is restricted to the fundamental resonance case, that is, . The energy of system is obtained from infinite dimensional system of coupled ordinary differential equations. For 2, it has been observed that the energy of system decreases in the smaller domain of time and then remains constant. For 2 the energy of system has been damped out as the time progresses, while the energy grows without bound when 2. However, for the system exhibits the similar behavior as obtained in [6]. Fig. 2 depicts the energy and mode-amplitude response for the damping parameter 2. Fig. 2(a) represents the energy of the damped system, while Fig. 2(b), Fig. 2(c) and Fig. 2(d) represent, respectively, the first, the second and the third mode-amplitude responses. It can clearly be seen in these figures that both the mode-amplitude response and energy are damped out as time increases. This implies that the mode-response and energy response exhibits the similar behavior, so there does not seem a problem in mode-truncation. The energy and mode responses are obtained for 2 and is shown in Fig. 3. The energy response is shown in Fig. 3(a), while Fig. 3(b), Fig. 3(c) and Fig. 3(d) represent the first, the second and the third mode-amplitude responses, respectively. It can easily be observed in these figures that the energy and mode-amplitude responses have similar behavior, so mode-truncation for 2 may also be possible. Finally, Fig. 4(a) represents the energy for 2, and it grows exponentially. Fig. 4(b), Fig. 4(c) and Fig. 4(d) depict, respectively, the first, the second and the third mode-amplitude responses for 2. In these figures, it can easily be observed that both the energy and mode-amplitude responses have different behavior, so the mode-truncation for this case does not seem possible.

– Case I. 2.

Fig. 2For ε= 0.01, δ= 2 and x= 0.5: a) energy E vs time t, b) first mode, c) second mode, d) third mode

a)

b)

c)

d)

– Case II. 2.

Fig. 3For ε= 0.01, δ= 5 and x= 0.5: a) energy E vs time t, b) first mode, c) second mode, d) third mode

a)

b)

c)

d)

– Case III. 2.

Fig. 4For ε= 0.01, δ= 0.05 and x= 0.5: a) energy E vs time t, b) first mode, c) second mode, d) third mode

a)

b)

c)

d)

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have examined the applicability of truncation method for string-like model under the effect of viscous damping. Axial velocity of the string is assumed to be sinusoidal, time-varying and small compared to wave velocity. In order to obtain the formal approximations of the solutions of the initial-boundary value problem, a two timescales perturbation method along with Fourier-sine series is employed. It turns out that there are infinitely many values of parameter which give rise to the resonances in system. The fundamental resonant, detuning and non-resonant cases have been discussed. In resonant-case, the mode-amplitude response and energy of the damped system are computed. For 2 and 2, it has been shown that the mode-truncation may not be problematic for damped string-like model as was claimed in [6, 33]. However, for 2, the mode-truncation is not possible due to exponential growth of the energy of damped system and oscillatory behaviour of mode-amplitude responses.

In addition to this, the energy of system in the neighbourhood of fundamental resonance is discussed. It has been observed that the system remains stable for detuning parameter ±2 and damping parameter 0. In case of detuning parameter 2, the energy of system is shown to be bounded for damping parameter , while the system remains unstable for . However, the system remains stable due to trigonometric functions for detuning parameter . Furthermore, for non-resonant case, the system is shown to be stable.

References

-

Zhu W. D., Ni J., Huang J. Active control of translating media with arbitrarily varying length. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 123, Issue 3, 2001, p. 347-358.

-

Yani R. M., Darabi E. An analytical solution for vibration of elevator cables with small bending stiffness. International Journal of Mechanical, Aerospace, Industrial, Mechatronic and Manufacturing Engineering, Vol. 6, Issue 10, 2012, p. 2050-2054.

-

Zhu W. D., Chen Y. Theoretical and experimental investigation of elevator cable dynamics and control. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 128, Issue 1, 2005, p. 66-78.

-

Sandilo S. H., Van Horssen W. T. On a cascade of autoresonances in an elevator cable system. Nonlinear Dynamics, Vol. 80, Issue 3, 2015, p. 1613-1630.

-

Kaczmarczyk S., Ostachowicz W. Transient vibration phenomena in deep mine hoisting cables. Part I: Mathematical model. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 262, Issue 2, 2003, p. 219-244.

-

Suweken G., Van Horssen W. T. On the transversal vibrations of a conveyor belt with a low and time-varying velocity. Part I: the string-like case. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 264, Issue 1, 2003, p. 117-133.

-

Ponomareva S. V., Van Horssen W. T. On transversal vibrations of an axially moving string with a time-varying velocity. Non-linear Dynamics, Vol. 50, Issues 1-2, 2007, p. 315-323.

-

Ponomareva S. V., Van Horssen W. T. On the transversal vibrations of an axially moving continuum with a time-varying velocity: Transient from string to beam behavior. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 325, Issues 4-5, 2009, p. 959-973.

-

Pakdemirli M., Öz H. R. Infinite mode analysis and truncation to resonant modes of axially accelerated beam vibrations. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 311, Issues 3-5, 2008, p. 1052-1074.

-

Kuiper G. L., Metrikine A. V. On stability of a clamped-pinned pipe conveying fluid. Heron, Vol. 49, Issue 3, 2004, p. 211-232.

-

Öz H. R., Boyaci H. Transverse vibrations of tensioned pipes conveying fluid with time-dependent velocity. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 236, Issue 2, 2000, p. 259-276.

-

Ulsoy A. G., Mote C. D., Szymni R. Principal developments in band saw vibration and stability research. Holz als Roh- und Werkst, Vol. 36, Issue 7, 1978, p. 273-280.

-

Andrianov I. V., Awrejcewicz J. Dynamics of a string moving with time-varying speed. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 292, Issues 3-5, 2006, p. 935-940.

-

Gaiko N. V., Van Horssen W. T. On the lateral vibrations of a vertically moving string with a harmonically varying length. International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Houston, 2015.

-

Van Horssen W. T., Ponomareva S. V. On the construction of the solution of an equation describing an axially moving string. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 287, Issues 1-2, 2005, p. 359-366.

-

Gaiko N. V., Van Horssen W. T. On transversal oscillations of a vertically translating string with small time-harmonic length variations. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 383, 2016, p. 339-348.

-

Akkaya T., Van Horssen W. T. On the Transverse vibrations of strings and beams on semi-infinite domains. Procedia IUTAM, Vol. 19, 2016, p. 266-273.

-

Sandilo S. H., Van Horssen W. T. On variable length induced vibrations of a vertical string. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 333, Issue 11, 2014, p. 2432-2449.

-

Malookani R. A., Sandilo S. H., Sheikh A. H. On (non) applicability of a mode-truncation of a damped traveling string. Mehran University Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, Vol. 38, Issue 2, 2019, p. 471-478.

-

Marynowski K., Kapitaniak T. Zener internal damping in modelling of axially moving viscoelastic beam with time-dependent tension. International Journal of Non- Linear Mechanics, Vol. 42, Issue 1, 2007, p. 118-131.

-

Krenk S. Vibrations of a taut cable with an external damper. Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 67, Issue 4, 2000, p. 772-776.

-

Vaiana N., Spizzuoco M., Serino G. Wire rope isolators for seismically base-isolated lightweight structures: experimental characterization and mathematical modelling. Engineering Structures, Vol. 140, 2017, p. 498-514.

-

Vaiana N., Marmo F., Sessa S., Rosati L. Modelling of the hysteretic behavior of wire rope isolators using novel rate-dependent model. Nonlinear Dynamics of Structures, Systems and Devices, Vol. 1, 2020, p. 309-317.

-

Vaiana N., Sessa S., Marmo F., Rosati L. An accurate and computationally efficient uniaxial phenomenological model for steel and fiber reinforced elastomeric bearing. Composite Structures, Vol. 211, Issue 1, 2019, p. 196-212.

-

Shahruz S. M. Stability of a nonlinear axially moving string with the Kelvin-Voigt damping. Journal of Vibrations and Acoustics, Vol. 131, Issue 1, 2009, p. 014501.

-

Darmawijoyo, Van Horssen W. T. On the weakly damped vibrations of a string attached to a spring mass dashpot system. Journal of Vibration and Control, Vol. 9, Issue 11, 2003, p. 1231-1248.

-

Sandilo S. H., Van Horssen W. T. On boundary damping for an axially moving tensioned beam. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 134, Issue 1, 2012, p. 0110051.

-

Gaiko N. V., Van Horssen W. T. On the transverse, low frequency vibrations of a traveling string with boundary damping. Journal of Vibration and Acoustics, Vol. 137, Issue 4, 2015, p. 9-11.

-

Darmawijoyo, Van Horssen W. T. On boundary damping for a weakly nonlinear wave equation. Non-linear Dynamics, Vol. 30, Issue 2, 2002, p. 179-191.

-

Darmawijoyo, Van Horssen W. T., Clément P. H. On a Rayleigh wave equation with boundary damping. Non-Linear Dynamics, Vol. 33, 2003, p. 399-429.

-

Chen E. W., Ferguson N. S. Analysis of energy dissipation in an elastic moving string with a viscous damper at one end. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 333, Issue 9, 2014, p. 2556-2570.

-

Malookani R. A., Dehraj S., Sandilo S. H. Asymptotic approximations of the solution for a traveling string under boundary damping. Journal of Applied and Computational Mechanics, Vol. 5, Issue 5, 2019, p. 918-925.

-

Malookani R. A., Van Horssen W. T. On resonances and the applicability of Galerkin’s truncation method for an axially moving string with time-varying velocity. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 344, 2015, p. 1-17.

-

Gaiko N. Transversal Waves and Vibrations in Axially Moving Continua. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Delft, Netherlands, 2015.