Abstract

This study conducted detailed research and analysis on the setting time, compressive strength, bond strength, and bond splitting tensile strength of anti-washout cement with polyacrylamide (PAM) content. The results indicate that the initial and final setting times of the paste show a linear increasing trend with PAM addition. The early compressive strength exhibits a significant reduction, while the growth rate of compressive strength from 7 d to 28 d markedly accelerates after overcoming the hydration barrier. Compared to land-cast specimens, underwater-cast calcium sulfoaluminate cement and ordinary Portland cement show limited reductions in compressive strength and splitting tensile strength. However, due to the effects of adsorbed water films and alkali metal leaching, their bond splitting tensile strengths decrease by 40.30 % and 70.42 %, respectively. The chloride penetration depth and non-steady-state chloride migration coefficient (DRCM) are reduced by approximately 34 % and 42 %, which correlates with PAM-induced reductions in hydration porosity and structural connectivity of the specimens.

1. Introduction

Underwater non-dispersible cement-based materials have garnered extensive research in water-related engineering, coastal projects, and island/reef construction due to their exceptional anti-washout properties and workability [1]. Traditional anti-washout admixtures for underwater non-dispersible concrete primarily include cellulose derivatives, polysaccharides, and acrylate-based polymers [2, 3].

Current research on underwater non-dispersible concrete focuses on two aspects: anti-washout performance and rheological behavior [4-7]. For anti-washout testing, Hao et al. refined evaluation methods by combining the plunge test with pH measurement [4]. Song [8] improved standardized protocols using pH and turbidity analyses: 500 g of slurry was uniformly poured into an 800 ml water-filled beaker in ten batches, with post-washout turbidity and pH of the supernatant used to characterize anti-washout performance. This approach, combined with bleeding resistance, fluidity, and compressive strength tests, validated the applicability of Hi-FA materials in underwater environments. Papo et al. [9, 10] employed a coaxial cylinder viscometer (Rotovisko-Haake) to reveal that polycarboxylate ether polymers induce shear-thickening behavior in cement paste, attributed to electrostatic adsorption and steric hindrance effects. Hoffman [11] attributed shear thickening to the transition of particle arrangements from ordered to disordered states under high shear rates, where energy dissipation increases due to particle “jamming”. Hao et al. [7] further correlated polyacrylamide (PAM)-modified slurry’s plastic viscosity with anti-washout performance.

Some scholars have explored the mechanisms behind changes in anti-washout performance and rheological properties. Studies on anti-washout polymer physicochemical properties include Bessaies-Bey [12], who demonstrated that calcium ions promote entanglement and microgel formation in anionic PAM, with polymer chains bridging cement particles to enhance plastic viscosity and yield stress. Hou et al. [13-16] used molecular dynamics to show that incorporating calcium hydroxide nanoparticles into hydrogel networks increases crosslinking density, improving tensile strength and elastic modulus via PAM chain reinforcement. Yang [17] quantified polymer-cement water exchange through hydration peak shifts and moisture gradients, identifying a "two-stage desorption" mechanism driven by osmotic pressure.

While existing research emphasizes micro-mechanical properties, systematic studies on engineering performance – particularly the impacts of underwater casting on mechanical and durability properties – remain limited. Addressing this gap, this study first investigates the setting time and compressive strength of PAM-modified underwater non-dispersible concrete, interpreted through a micro-mesoscale model. Further comparative analyses evaluate compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and bond splitting tensile performance of OPC and CSA cement under underwater and land-cast conditions. Durability assessments focus on impermeability differences, providing critical insights for practical underwater applications.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

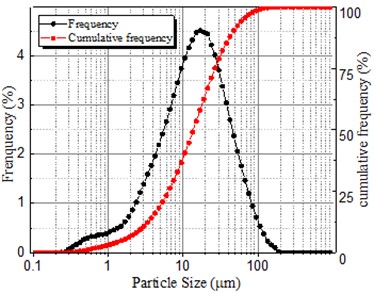

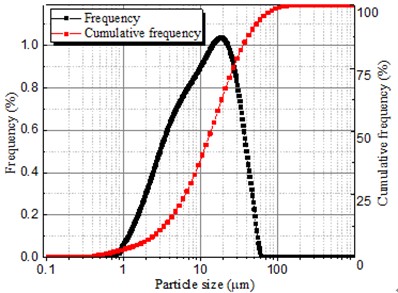

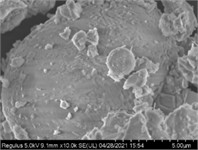

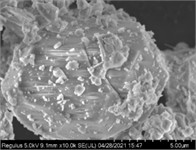

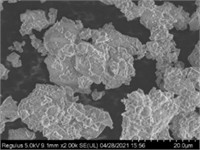

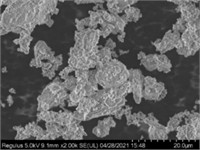

Ordinary Portland cement (OPC) and calcium sulfoaluminate cement (CSA) are used as the primary materials for underwater non-dispersible paste. The OPC (P.O.42.5R) and CSA comply with the Chinese standards Common Portland Cement (GB175-2020) and Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement (GB20472-2006), respectively. The chemical compositions of the cements, measured using a Panalytical Axios Fast X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, are listed in Table 1. Particle size distributions were analyzed via dry powder multi-point sampling with a Bettersize 2000 laser particle size analyzer (Fig. 1). For OPC, the frequency distribution diameters D10, D50, D90 were 2.987 μm, 14.50 μm, and 49.18 μm, respectively, with a specific surface area of 367.9 m2/kg. CSA exhibited D10, D50, D90 values of 2.75 μm, 11.10 μm, and 31.60 μm, respectively, and a specific surface area of 923.5 m2/kg. Cement particle morphologies at varying scales were observed using an FEI INSPECT F50 field-emission scanning electron microscope (Fig. 2).

Table 1Chemical composition of OPC and CSA cement (Unit: %)

Compositions | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | SO3 | MgO | K2O | Na2O | others |

OPC | 66.65 | 17.88 | 6.35 | 3.72 | 2.66 | 0.61 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 1.16 |

CSA | 46.73 | 8.14 | 28.17 | 2.48 | 12.01 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 0.000 | 1.43 |

The polyacrylamide (PAM) used has a molecular weight of 10 million Daltons, a density of 1.0±0.1 g/cm3, and appears as white to pale crystalline granules. A PCA®-Ⅰ polycarboxylate superplasticizer, produced by Jiangsu Sobute New Materials Co., Ltd., was employed. The anti-washout paste had a water-to-cement ratio of 0.5, with a superplasticizer dosage of 2.0 % by cement mass. For studies on setting time and compressive strength, PAM content ranged from 0.0 % to 1.4 %. During comparative analyses of OPC and CSA under underwater/land-cast conditions, the optimal PAM dosage was fixed at 0.6 % [7].

2.2. Setting time and compressive strength

The mixing process was carried out using a cement paste mixer. Prior to mixing, the mixing bowl and blades were wiped with a wet cloth. The mixing water was poured into the bowl, followed by the careful addition of cement within 5-10 seconds to minimize splashing. The bowl was then mounted into the mixer and raised to the mixing position. The mixer was started and operated at low speed for 120 seconds, followed by a 15-second pause during which any paste adhering to the blades or bowl wall was scraped into the center. Subsequently, high-speed mixing was conducted for another 120 seconds before stopping. The freshly cast specimens were cured in a controlled environment at 20 °C and 95 % relative humidity. For setting time measurements, parallel tests were performed and the average value was reported. For strength tests, triplicate parallel experiments were conducted, and the results were averaged. Data variability was indicated using error bars.

Fig. 1Particle size distribution of OPC and CSA cement

a) OPC

b) CSA

Fig. 2Particle size distribution of OPC and CSA cement

a) OPC

b) OPC

c) CSA

d) CSA

Setting times of PAM-modified pastes were determined per the Chinese standard Test Methods for Water Requirement of Normal Consistency, Setting Time, and Soundness of Cements (GB/T 1346-2011). Initial setting time was defined as when the Vicat needle penetration depth fell below 25.0 mm, and final setting time as when no visible penetration occurred. Uniaxial compressive strength tests followed Test Method for Cement Mortar Strength (GB/T 17671-2021), using 50.0 mm cubic specimens cured for 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, and 28 d.

2.3. Splitting tensile and bond splitting tensile performance

Splitting tensile and bond splitting tensile strengths were evaluated according to Test Code for Underwater Non-Dispersible Concrete (DL/T 5117-2000). Splitting tensile tests used 70.7 mm cubic specimens loaded at 0.5 N/mm2. For bond tests, split specimens (70.7 mm×70.7 mm×35.35 mm) were surface-cleaned and recast under land (25 °C) or underwater conditions, then cured to specified ages.

2.4. Impermeability

Chloride resistance was assessed via the rapid chloride migration coefficient method (Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Ordinary Concrete, GB/T 50082-2009), using a CABR-RCMP multifunctional tester (China Academy of Building Research). Testing parameters included adjustable DC voltage (0-60 V), current (0-10 A), 0.1 mol/L AgNO3spray, 10 % NaCl catholyte, and 0.3 mol/L NaOH anolyte. Specimens were cured for 28d and tested over 24.0 h.

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Setting time and compressive strength

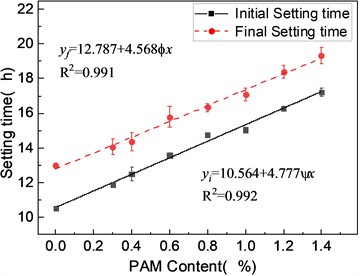

The setting time and compressive strength of cement paste with different PAM dosages were tested, and the results are shown in Fig. 3(a). The experimental data were fitted using a solid black line and a red dashed line, with correlation coefficients () of 0.993 and 0.991, respectively. Both the initial and final setting times exhibited a linear positive correlation with PAM content. This is attributed to the retarding effect of PAM molecules on early-stage hydration, which delays the solidification process of the paste. This inhibitory effect intensifies with increasing polymer content, leading to a continuous linear increase in setting times. The initial and final setting times increased at rates of 0.4777 and 0.4568, respectively, with increasing PAM content. While this phenomenon has been mentioned in [18], no reasonable explanation was provided. According to the nucleation mechanism of hydration established before (as shown in Fig. 4), as hydration progresses, the later-stage hydration rate of the accelerator gradually increases due to the overcoming of the hydration barrier, resulting in faster particle precipitation and coagulation. Consequently, the growth rate of the final setting time slightly decreases.

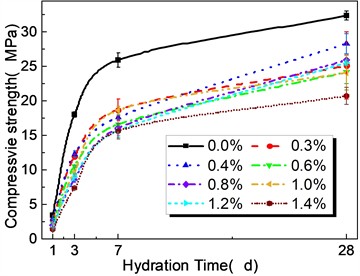

The 28-day compressive strength of pure cement paste was 33.2 MPa, whereas the addition of PAM led to a significant reduction, maintaining a range of 21-28 MPa (Fig. 1(b)). Due to PAM’s retardation effect on early hydration, the 1-day and 3-day compressive strengths showed a considerable gap compared to the reference sample. However, after the hydration barrier was overcome, the strength growth rate of the PAM-modified paste between 7 and 28 days exceeded that of the reference sample, gradually narrowing the compressive strength gap with prolonged curing. By the 28-day mark, the hydration degree of all PAM pastes became consistent. Nevertheless, due to their higher macro- and micro-porosity, as well as poor structural integrity and continuity, the compressive strength of the specimens remained at a relatively low level.

Fig. 3Setting time and compressive strength of slurry with different PAM content

a)

b)

3.2. Mechanical properties

Considering the practical engineering application quality of grouts, anti-washout Ordinary Portland Cement and Calcium Sulfoaluminate cement cement pastes with a water-to-cement ratio of 0.5, 2.0 % superplasticizer, and 0.6 % polyacrylamide (PAM) content were cast underwater and on land, respectively. A comprehensive evaluation of the anti-washout grout was conducted by comparatively analyzing hardened properties such as compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, bond splitting tensile performance at different curing ages.

Fig. 4Mechanism model diagram of materials with different PAM content [19, 20]

![Mechanism model diagram of materials with different PAM content [19, 20]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25184/25184-img9.jpg)

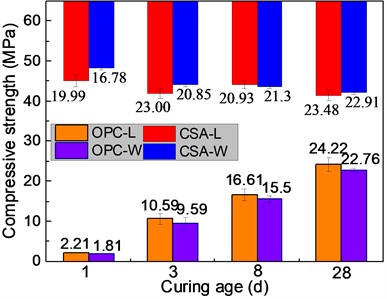

3.2.1. Compressive strength

The compressive strengths of underwater- and land-cast OPC and CSA cement specimens are shown in Fig. 5(a). Compared to land-cast samples, underwater-cast OPC cement exhibited reduced strength but maintained a low mass loss rate. The uniaxial compressive strengths of underwater-cast specimens at 1 d, 3 d, 8 d, and 28 d were 81.90 %, 90.56 %, 93.32 %, and 93.97 % of their land-cast counterparts, respectively. In contrast, due to its rapid early hydration, CSA cement achieved high underwater strength (16.78 MPa) at 1d, with underwater compressive strengths at 1 d, 3 d, 8 d, and 28 d being 83.94 %, 90.65 %, 99.18 %, and 97.57 % of land-cast specimens, respectively. Additionally, owing to more stable environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity), underwater-cast specimens demonstrated lower strength variability than land-cast ones.

Fig. 5Compressive strength and Split tensile strength of OPC and CSA casted underwater and on land

a)

b)

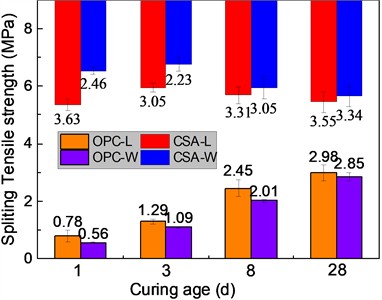

3.2.2. Splitting tensile strength

The splitting tensile strengths of underwater- and land-cast OPC and CSA cement specimens are presented in Fig. 5(b). Similar to compressive strength, underwater-cast OPC specimens showed reduced splitting tensile strength but with an overall minor strength loss. The underwater splitting tensile strengths at 1 d, 3 d, 8 d, and 28 d were 71.79 %, 84.50 %, 82.04 %, and 95.64 % of land-cast specimens, respectively. For CSA cement, these values were 67.77 %, 73.11 %, 92.39 %, and 94.08 %, respectively. Notably, the reduction in splitting tensile strength was more pronounced than that in compressive strength.

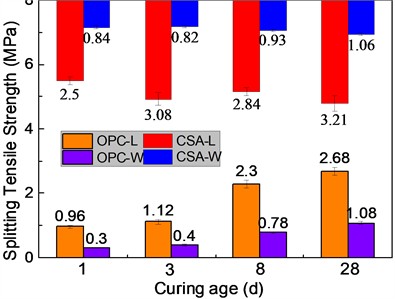

3.2.3. Splitting tensile performance

The bond splitting tensile performance of underwater- and land-cast Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) and Calcium Sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement specimens is illustrated in Figure 7. For OPC cement, the land-cast specimens exhibited a bond strength of 0.96 MPa at 1d. As hydration progressed, the bonding performance gradually improved, reaching 3.05 MPa at 28 d – comparable to the splitting tensile strength of pristine cement paste. In contrast, the underwater-cast specimens demonstrated bond splitting tensile strengths of only 21.88 %, 35.71 %, 33.91 %, and 40.30 % of their land-cast counterparts at 1 d, 3 d, 8 d, and 28 d, respectively. Notably, the growth rate of underwater bond strength significantly decelerated over time. CSA cement, benefiting from its rapid early hydration, achieved a land-cast bond strength of 2.5 MPa at 1 d – 70.42 % of its 28 d splitting tensile strength. However, underwater-cast specimens showed reduced performance, with bond strengths consistently measuring 26.0 %-29.0 % of land-cast values across all tested ages (1 d, 3 d, 8 d, and 28 d).

Fig. 6Bond strength of OPC and CSA cement casted underwater and on land

3.3. Impermeability strength

At a curing age of 28 days, the 1-day permeability test results of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) and Calcium Sulfoaluminate (CSA) cement are shown in Fig. 9, where (a), (b), (c), and (d) represent land-cast and underwater-cast specimens of OPC and CSA cement, respectively. The white coloration indicates the chromogenic reaction between nitrate solution and chloride ions, representing the actual penetration depth of chloride ions. The impermeability of the specimens was characterized by both penetration depth and the non-steady-state chloride migration coefficient, with results summarized in Table 2. The penetration depth was calculated using the bisection method, while the non-steady-state chloride migration coefficient was determined by the following formula:

where, refer to the non-steady-state chloride migration coefficient (×10-12 m2/s); refer to absolute value of the applied voltage (V); refer to average temperature of the anolyte at the beginning and end of the test (°C); refer to thickness of the specimen (mm); refer to average chloride ion penetration depth (mm); refer to test duration (h).

Fig. 7Chloride permeation test results of underwater non - dispersible slurry

a)

b)

c)

d)

Table 2Results of PAM permeation depth on the surface and underwater specimens and unsteady chloride migration coefficient

Samples | Condition | (mm) | (V) | (℃) | (mm) | ||

OPC | Land | 28.0 | 10 | 27.63 | 50.7 | 42.69 | 42.79 |

28.3 | 10 | 27.96 | 50.2 | 42.88 | |||

Underwater | 38.9 | 10 | 29.13 | 51.9 | 63.10 | 62.78 | |

37.8 | 10 | 29.37 | 53.1 | 62.45 | |||

CSA | Land | 37.9 | 10 | 27.63 | 51.3 | 60.41 | 60.11 |

38.2 | 10 | 27.96 | 50.2 | 59.81 | |||

Underwater | 50.2 | 10 | 29.37 | 51.6 | 83.03 | 83.40 | |

50.4 | 10 | 29.13 | 51.9 | 83.77 |

The data reveal that underwater-cast specimens exhibit greater chloride ion penetration depths compared to land-cast counterparts. For OPC, the penetration depth increased from 28.15 mm to 38.35 mm (36.23 % rise), while CSA showed an increase from 38.05 mm to 50.3 mm (32.19 % rise). Correspondingly, the non-steady-state chloride migration coefficients were significantly higher in underwater conditions: OPC increased from 4.279×10-12 m2/s to 6.278×10-12 m2/s (46.78 % rise), and CSA rose from 6.509×10-12 m2/s to 9.410×10-12 m2/s (38.75 % rise). The reduced chloride resistance of underwater-cast specimens is attributed to higher porosity and weakened structural connectivity caused by PAM, with OPC and CSA demonstrating comparable degradation rates. Notably, CSA cement inherently exhibits lower chloride penetration resistance than OPC. This phenomenon occurs because sulfate depletion in CSA systems triggers ettringite phase transformation into monosulfoaluminate, which reacts with chlorides to form Friedel’s salt – a process that intrinsically compromises chloride barrier performance.

According to engineering standards [16], underwater-cast cementitious materials need only achieve 80.0 % compressive strength and 60.0 % splitting tensile strength of their land-cast equivalents for practical applications. The developed OPC and CSA formulations in this study surpassed these thresholds, attaining 93.97 %/97.57 % (compressive) and 95.64 %/94.84 % (splitting tensile) of land-cast performance at 28 days. However, splitting tensile strength was reduced to approximately one-third of land-cast values due to interfacial water film formation and OPC alkali leaching, accompanied by a 45.0 % increase in chloride migration coefficients. CSA cement's rapid early-strength development makes it particularly valuable for emergency underwater repairs. Conversely, OPC’s superior chloride resistance positions it as the preferred choice for durable underwater concrete structures requiring long-term serviceability.

4. Conclusions

Through the experimental research and analysis in this paper, the main conclusions are as follows:

1) The initial and final setting times of the paste show a linear increasing trend with the addition of PAM. Due to the shortened phase boundary reaction process in the middle and late stages, the final setting time exhibits a slower rate of increase compared to the initial setting time. Specifically, for every 0.2 % increase in PAM content, the initial and final setting times increase by 0.96 h and 0.91 h respectively. The early compressive strength of PAM paste is significantly lower compared to cement paste. With the breakthrough of hydration barrier, the growth rate of compressive strength from 7 d to 28 d is significantly improved. However, due to the increased macro and micro porosity of hardened specimens and reduced material structural compactness, the 28 d compressive strength still does not reach that of the reference sample.

2) For ordinary Portland cement and calcium sulfoaluminate cement, the 28 d compressive strengths of underwater-cast specimens are 93.97 % and 97.57 % of land-cast specimens respectively; the 28d splitting tensile strengths are 95.64 % and 94.08 %; and the 28d bond splitting tensile strengths are 40.30 % and 70.42 %. The reduction in bond splitting tensile strength is mainly related to the adsorbed water film on specimen surfaces and the leaching of alkali metals.

3) The increases in chloride penetration depth for underwater-cast specimens of ordinary Portland cement and calcium sulfoaluminate cement are 36.23 % and 32.19 % respectively, while the non-steady-state chloride migration coefficients increase by 46.78 % and 38.75 % respectively. This is because under the influence of PAM, the increased porosity degree and reduced connectivity of specimen structure weaken their impermeability performance. The consistent weakening amplitude indicates the same degree of influence from pore structure.

4) The underwater non-dispersible calcium sulfoaluminate cement, with its characteristics of rapid early strength development and high bond strength, is suitable for emergency rescue tasks in water-related projects. The underwater-cast specimens of ordinary Portland cement have better application prospects in underwater structure durability due to their better chloride impermeability.

Although this study provides a comprehensive investigation into the compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, bond splitting tensile strength, and impermeability of anti-washout cement-based materials, further research remains essential to support their practical implementation in construction applications. Critical areas for future work include evaluating long-term durability in marine environments, resistance to chloride ion ingress, and washout resistance under turbulent flow conditions.

References

-

H. Lu, X. Sun, and H. Ma, “Anti-washout concrete: an overview,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 344, p. 128151, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128151

-

T. Kawai, “Non-dispersible underwater concrete using polymers-the production, performance and potential of polymers in concrete,” Brighton polytechnic, pp. 24–27, 1988.

-

B. Han, L. Zhang, and J. Ou, “Chapter 22: non-dispersible underwater concrete,” in Smart and Multifunctional Concrete Toward Sustainable Infrastructures, 2017, pp. 369–377.

-

H. Lu, Z. Tian, M. Zhang, X. Sun, and Y. Ma, “Study on testing methods for water resistance of underwater cement paste,” Materials and Structures, Vol. 54, No. 5, pp. 180–180, Aug. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-021-01772-0

-

Z. Su, C. Li, G. Jiang, J. Li, H. Lu, and F. Guo, “Rheology and thixotropy of cement pastes containing polyacrylamide,” Geofluids, Vol. 2022, pp. 1–10, Jul. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1029984

-

K. Baluch, S. Q. Baluch, H.-S. Yang, J.-G. Kim, J.-G. Kim, and S. Qaisrani, “Non-dispersive anti-washout grout design based on geotechnical experimentation for application in subsidence-prone underwater karstic formations,” Materials, Vol. 14, No. 7, p. 1587, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14071587

-

H. Lu, C. Li, G. Jiang, H. Fan, X. Zuo, and H. Liu, “Rheology properties of underwater cement paste with non-ionic polyacrylamide,” Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering, 2023.

-

B.-D. Song, B.-G. Park, Y. Choi, and T.-H. Kim, “Determining the engineering characteristics of the Hi-FA series of grout materials in an underwater condition,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 144, pp. 74–85, Jul. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.101

-

A. Papo and L. Piani, “Effect of various superplasticizers on the rheological properties of Portland cement pastes,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 34, No. 11, pp. 2097–2101, Nov. 2004, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.03.017

-

M. Cyr, C. Legrand, and M. Mouret, “Study of the shear thickening effect of superplasticizers on the rheological behaviour of cement pastes containing or not mineral additives,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 30, No. 9, pp. 1477–1483, Sep. 2000, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-8846(00)00330-6

-

R. L. Hoffman, “Explanations for the cause of shear thickening in concentrated colloidal suspensions,” Journal of Rheology, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 111–123, Jan. 1998, https://doi.org/10.1122/1.550884

-

H. Bessaies-Bey, R. Baumann, M. Schmitz, M. Radler, and N. Roussel, “Effect of polyacrylamide on rheology of fresh cement pastes,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 76, pp. 98–106, Oct. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.05.012

-

D. Marchon, S. Kawashima, H. Bessaies-Bey, S. Mantellato, and S. Ng, “Hydration and rheology control of concrete for digital fabrication: Potential admixtures and cement chemistry,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 112, pp. 96–110, Oct. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.05.014

-

Z.-J. Huang, T.-B. Xu, D. Z. Zhu, and S.-D. Zhang, “Simulation of open channel flows by an explicit incompressible mesh-free method,” Journal of Hydrodynamics, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 287–298, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42241-023-0020-4

-

A. Khoshkonesh, B. Nsom, F. Bahmanpouri, F. A. Dehrashid, and A. Adeli, “Numerical study of the dynamics and structure of a partial dam-break flow using the vof method,” Water Resources Management, Vol. 35, No. 5, pp. 1513–1528, Mar. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-021-02799-2

-

P. Zhang, S. Sun, and Y. Chen, “Coupled material point Lattice Boltzmann method for modeling fluid-structure interactions with large deformations,” Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, Vol. 385, pp. 114040–114040, 2021.

-

J. Yang, F. Wang, Z. Liu, Y. Liu, and S. Hu, “Early-state water migration characteristics of superabsorbent polymers in cement pastes,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 118, pp. 25–37, Apr. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.02.010

-

R. Krstulović and P. Dabić, “A conceptual model of the cement hydration process,” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 693–698, May 2000, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-8846(00)00231-3

-

H. Lu, B. Dai, C. Li, H. Wei, and J. Wang, “Flocculation mechanism and microscopic statics analysis of polyacrylamide gel in underwater cement slurry,” Gels, Vol. 11, No. 2, p. 99, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11020099

-

C. Zhang et al., “A new clay-cement composite grouting material for tunnelling in underwater karst area,” Journal of Central South University, Vol. 26, No. 7, pp. 1863–1873, Aug. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-019-4140-5

About this article

This research work was financially supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFC3015903), 2023 Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Open Bidding for Selecting the Best Candidates (No. Rq424001), the Fundamental Research Funds for Basic Research of Public Welfare Scientific Research Institutes (No. Y424009).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.