Abstract

Drum-type machines have become widely used in many industries for processing various granular materials. An innovative direction for significantly increasing the energy efficiency of such equipment is the use of self-oscillating working processes. Self-excitation of auto-oscillations allows you to bring into pulsating flow and activate the passive part of the intra-chamber filling and significantly enhance the interaction of granular particles with each other and with the surrounding environment. The purpose of the study is to build a mathematical model of the conditions and factors of oscillatory instability of the flow of polydisperse granular filling in the chamber of a rotating drum. The research methodology includes analytical modeling of wave processes and experimental modeling of manifestations of instability of the filling flow. The inertial mode of flow of the active part of the filling in a shear flow state is analyzed, the behavior of which is described using averaged values. Based on the results obtained, an increase in instability with an increase in the dilatancy of the medium during deformation is established and the destabilizing effect of the damping action of the fine fraction on the interaction of particles of the coarse fraction is revealed. The main scientific novelty of this study is the identification of the regularities of the unsteady motion of the oscillatory system of a filled drum. The study confirms the possibility of generating, under certain conditions, self-excitation of auto-oscillations of the intra-chamber filling, which is a decisive factor in the predicted intensification of the technological process. The results obtained are valuable for researchers and engineers involved in the study and design of innovative energy-efficient working processes of drum machines.

Highlights

- The oscillatory instability of the rotating drum intra-chamber polygranular filling flow were studied.

- The increase in filling positive dilatancy is the main instability factor.

- The filling fine fraction damping effect on the coarse fraction particles interaction is an additional instability factor.

- The damping reduces the bifurcation values of dilatancy and rotation speed.

- Instability causes self-excitation of the filling auto-oscillations.

1. Introduction

The high energy intensity of drum-type machines for processing granular materials is due to the low intensity of the fill circulation in the chamber of the rotating drum, a significant part of which is passive, does not undergo deformation and does not participate in the processing process. The problem of reducing the energy intensity of the working processes of drum machines remains relevant [1]. A new direction for radically increasing the energy efficiency of drum machines is the use of a self-oscillating working process. Self-excitation of auto-oscillations activates the passive part of the fill and intensifies its interaction with the working bodies and the environment. The first video recording of the self-oscillating mode of flow of a polygranular fill of a rotating drum was carried out in [2]. The overall effectiveness of the pioneering application of the self-oscillating grinding process in a tumbling mill was considered in [3]. The influence on self-oscillating grinding of changes in the degree of filling of the chamber with the fill [4], changes in the content of the crushed material [5] and simultaneous synergistic changes in the degree of filling and material content [6] was further studied. Qualitative conditions for the stability of the motion of the oscillatory system of a drum machine were established in [7]. In [8], individual parameters of the manifestation of the mechanism of loss of stability of the flow of granular filling were analyzed. However, the conditions for the occurrence of self-oscillations of the filling remained unclear. Instead, the behavior of the granular filling of a rotating drum has a clearly pronounced unstable character [9]. Such instability is manifested in the occurrence of an avalanche-like collapse of the free surface and the redistribution of particles inside the medium with the formation of cluster-like structures that can be stationary and drift and oscillate. An attempt to analytically determine the stability conditions of fast planar shear granular flows was made in [10]. The factors of loss of stability of translational shear flows were studied: the effect of a decrease in the density of the medium on the instability of the flow [11], on instability with shear bands [12] and on the formation of unstable cluster structures [13], and the effect of an increase in the dilatancy of the medium on the destabilization of the flow [14], on the collapse of granular columns [15] and on the collapse during the collapse of columns [16]. The factors of loss of stability of the flow of the rotating drum filling were also studied: granular temperature [17], dilatancy [18], compaction and dispersion [19], an increase in the content and increased dispersion of the fine fraction [20, 21]. However, at present, no models have been created to determine the strict conditions of stability of the flow during self-excitation of a complex transient pulsating motion of the intra-chamber filling. This is due to the insurmountable difficulties of analytical and numerical modeling and the increased complexity of instrumental experimental research of the behavior of a polygranular filling chamber of a rotating drum.

The aim of the work was to create a mathematical model of the conditions and factors of stability of flow in the chamber of a drum machine with a two-fraction filling. This will make it possible to predict the conditions of self-excitation of auto-oscillations of the filling and the effectiveness of the implementation of the self-oscillating process of processing granular materials when the parameters of the dynamic system vary. To achieve the goal, the following tasks were set: to identify the part of the filling where unstable flow modes arise; to perform analytical modeling of wave processes in the part of the filling with an unstable flow; to establish qualitative factors of unstable flow based on model analysis; to experimentally determine the quantitative influence of the state and structure of the two-fraction filling on the stability of flow.

2. Analytical research methodology

2.1. Filling flow modes

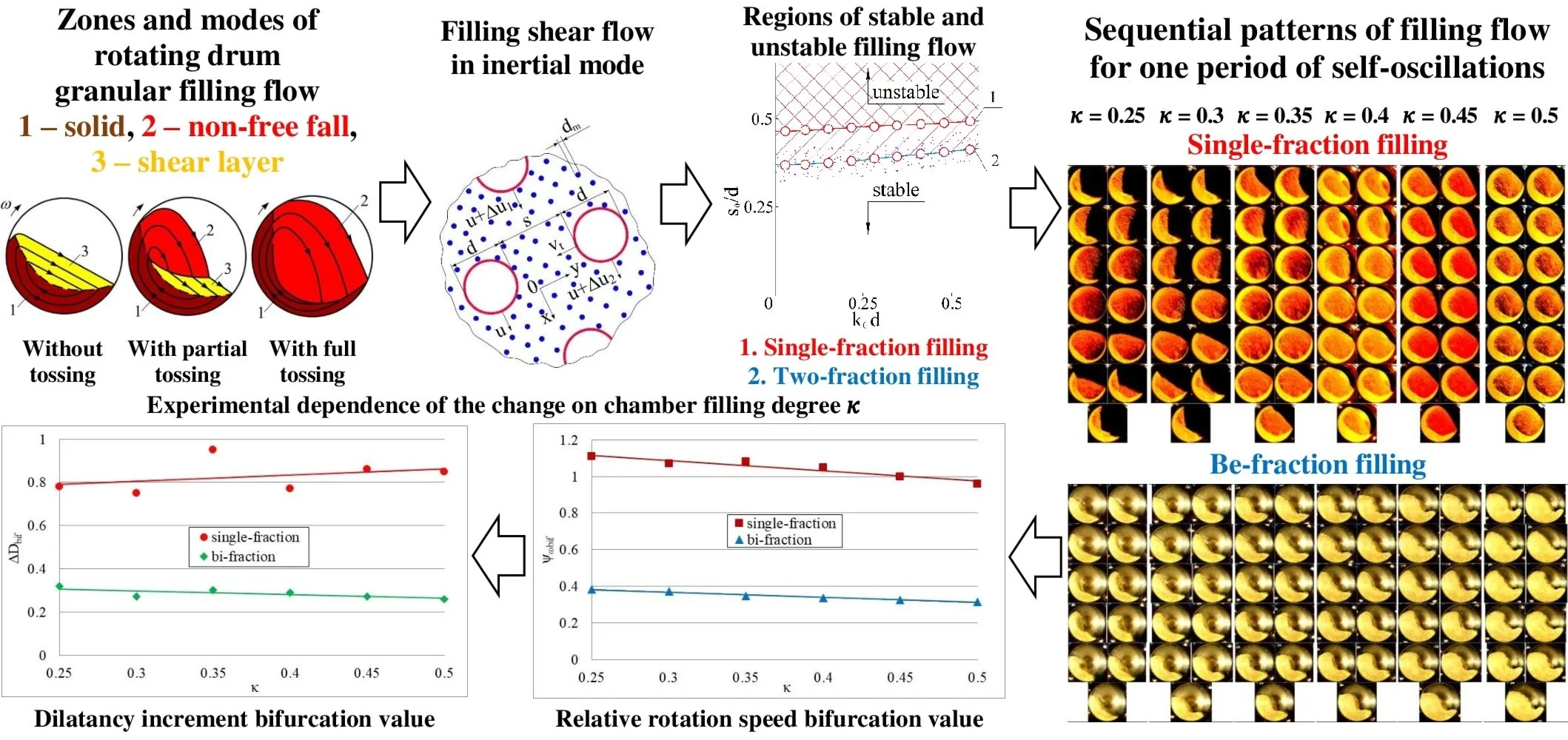

The granular filling of the drum, rotating with a moderate angular velocity around a horizontal axis, performs a circular flow in a three-phase mode (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1Scheme of zones and modes of flow of granular filling of a rotating drum in increasing ω: zones: 1 – solid, 2 – non-free fall, 3 – shear layer; modes of floq

a) Without tossing

b) With partial tossing

c) With full tossing

In the cross section of the drum chamber, three zones of flow of the granular medium can be conditionally distinguished. In the solid zone 1, the fill performs a quasi-solid flow together with the drum without relative movement of the particles. In the non-free fall zone 2, the particles are separated from the solid mass with subsequent fall with interaction between themselves. In the shear layer zone 3, a gravitational shear flow occurs near the free surface of the fill. At low , the mass fraction of the fill zone 1 prevails. With increasing , the fractions of zones 2 and 3 increase at the expense of zone 1. As approaches the critical value, the fraction of zone 2 reaches a maximum value, and the fraction of zone 3 tends to zero. At high , a flow regime in the form of a near-wall layer occurs, consisting only of zone 1.

In the zone of non-free fall 2, an inertial mode of behavior of the granular fill, which is in a state of shear flow, arises. This mode is realized at a low density of the medium and a large shear of velocities. Under such conditions, some gaps always appear between the particles of the fill. The interaction of the particles is carried out as a result of their continuous collision, and sliding plays an insignificant role. At the moment of collision, the particles change the direction of flow, describing zigzag trajectories.

2.2. Rheological filling model

The behavior of the granular filling of the drum in the inertial mode is further analyzed within the framework of the mechanics of continuous media, operating with quantities that are averaged over a large number of particles. The known results of experimental and theoretical studies of fast motions of granular media allowed us to make a simplifying assumption when formulating the problem under consideration that the volume fraction of solid spherical particles is practically constant, i.e. the filling can be considered weakly compressible. It was shown that in inertial granular shear flows the pressure and shear stress are proportional to the square of the shear velocity if the dynamic friction angle does not depend on it, in contrast to the dependence of a Newtonian fluid, where this relationship is linear.

Therefore, as a mathematical model of a dry incoherent weakly compressible granular drum filling, we can adopt the equation of an incompressible non-Newtonian fluid with a nonlinear relationship between the stress tensor and the flow shear rate. The flow has a moderate shear rate and the medium is described by functions of density, macroscopic velocity and thermal energy of particles. The original equations have the following form:

where const is the mass density, is the average (macroscopic) velocity, is the pressure, is the viscous stress tensor, is the bulk gravitational force, is the gravitational acceleration, is the time, is the coordinate, and are the directions of the coordinate.

3. Flow modeling

The considered granular filling of the drum chamber contains large particles of size and small particles of size (Fig. 2). Usually, the mass of large particles significantly exceeds the mass of small particles. It is assumed that the filling is not too dense and is under conditions that provide a large velocity shift, which corresponds to the inertial mode of flow. The energy of the chaotic motion of particles, which arises as a result of their collisions with each other, becomes quite significant and strongly affects the flow characteristics.

Fig. 2Schematic of the shear flow of filling in inertial mode

The behavior of the fill in the inertial mode is determined by the laws of conservation of mass, momentum, and granular thermal energy of chaotic particle motion, which can be written in tensor notation:

where is the granular temperature of the medium; is the granular thermal root-mean-square velocity of chaotic motion of particles; is the coefficient of granular thermal conductivity; is the coefficient of viscosity; is the reduction of energy of chaotic motion of large particles due to inelastic collisions; is the tensor of viscous stresses; , , is the indices.

The selected closing relations have the form [10]:

where is the average particle size (Fig. 2); is the mean free path of the particle; is the bulk density of the filling at maximum particle packing; is the velocity recovery coefficient during an inelastic impact; is the total duration between two collisions of particles; is the free path duration; is the contact duration; is the elastic wave velocity in the filling substance; is a dimensionless parameter; , , and are dimensionless coefficients of the order of unity.

The coefficients Eq. (3) are functions of the mean free path of the particles and their thermal velocity . Therefore, the desired functions in the original Eq. (2) will be , and .

4. Stability analysis

4.1. Initial equations

After using Cartesian coordinates , , and notation , Eq. (2) in components takes the form:

In the considered case of a shear granular flow, the dissipation of energy of the chaotic motion of the fill particles is compensated by the work of external forces driving the drum into rotation.

4.2. Linear equations

To remove the medium from the equilibrium state, one can add small perturbations to all functions characterizing the system. This means representing the desired functions in the form , , where stationary quantities are marked with the index 0, and small perturbations are marked with a dash. Such expressions can be substituted into Eq. (4) and leave only the first-order terms in terms of the amplitudes of the perturbations. In the case under consideration, the equilibrium functions are constant, except for the longitudinal velocity, and the velocity , where is the shear velocity. Then the system of equations for such amplitudes has the form:

Only the perturbations of density , velocity across the shear plane, and granular temperature propagating perpendicular to the shear plane of the flow , with amplitudes that do not depend on the coordinate y across the flow can be considered.

4.3. Dispersion equation

In the following, the consideration is limited to the case of perturbations with the wave vector , which defines plane waves with amplitude , wave number , and angular frequency .

Then the system of Eq. (5) reduces to a system containing the functions , and :

After replacing , , system Eq. (6) takes the form:

Perturbations in density, pressure, and transport coefficients can be expressed as functions of mean free path and granular temperature:

where , , .

By substituting Eq. (8) into system Eq. (7) and equating the corresponding determinant to zero, we can obtain a cubic equation for the complex frequency:

By introducing the value , we can transform Eq. (9) and obtain the dispersion equation:

where the coefficients of the equation are:

The real parts of the roots of Eq. (10) are decrements, and the imaginary parts of the roots are real frequencies with a minus sign.

4.4. Numerical solution of the dispersion equation

The solution of the dispersion equation has three roots, corresponding to three harmonics with time-varying density, velocity along the wave vector, and granular temperature. The problem of the stability of the flow of a granular fill is studied within the mechanics of continuous media. Therefore, the minimum wavelength of the considered disturbances must be much larger than the characteristic size, which can be taken as the sum of the diameter and the mean free path of large particles. was adopted, as well as the maximum wave number of perturbations , which does not violate the limits of applicability of the continuous medium model.

In the following, the stability of the shear flow with respect to small perturbations with wave numbers in the interval is considered. In the calculations, was adopted. The roots of the dispersion Eq. (9) were determined by the Cardano formulas for various parameters of the medium.

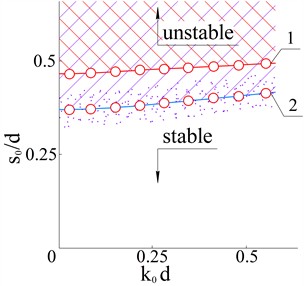

Calculations were performed for the case of single-grain filling only with large particles in the absence of small particles, when all bodies are considered absolutely rigid and the contact duration . A neutral curve (Fig. 3, line 1) was constructed, which separates the regions of stability and instability and corresponds to the zero value of the decrement . The part of the planes , which lies below the neutral curve, corresponds to positive values of and instability, and above the neutral curve – to negative values and, accordingly, stability. With an increase in the mean free path , the wave number , which characterizes the harmonic of the disturbance, which has neutral stability, increases slightly.

Fig. 3Scheme of regions of stable and unstable flow of filling in the planes k0d,s0/d: 1 – neutral curve for absolutely rigid large particles in the absence of small particles (single-fraction filling) (tc=0), 2 – neutral curve for deformable large particles in the presence of small particles (two-fraction filling) (tc=tf)

Fig. 3 also shows the neutral curve 2, which separates the regions of stability and instability for the case of polygranular filling in the presence of non-rigid small particles, when the large particles are considered deformed (). Compared to the case , this neutral curve 1 is shifted towards shorter mean free paths. An increase in the contact duration can cause the damping effect of the small particles on the collision of the large particles.

5. Experimental research methodology

Physical visualization of data was adopted as a method of experimental research, since the marginal edge effect of the flow of granular filling on the end wall of the chamber turned out to be insignificant. An experimental method of numerical modeling was applied based on visualization of the filling behavior in the chamber of a rotating drum. Visualization was carried out by fixing through a transparent end wall and subsequent processing of filling flow patterns in the cross-section of the chamber.

Measurements of linear dimensions and areas of geometric figures in the flow patterns were carried out using specialized computer programs. Graphical and statistical procedures for processing the obtained experimental results corresponded to the tasks set. The errors of the obtained measurement results were determined and estimated, the values of which depended on the rotation speed and the degree of filling of the chamber with filling during experimental research.

As a material for single-fraction and large fraction of two-fraction filling, a non-cohesive granular material with spherical particles with an average size . Cement with an average particle size was used as the material of the fine fraction of the two-fraction filling. The volumetric degree of filling of the drum chamber with the filling was estimated as [3-6], where is the volume of the coarse fraction at rest, is the radius of the drum chamber, and is the length of the chamber. The volumetric degree of filling of the volume of the two-fraction filling with particles of the fine fraction was estimated as [3-6], where is the volume of the fine fraction at rest. The value of was 0.4, which approximately corresponded to the complete filling of the gaps between the spherical particles of the coarse fraction at rest with fine particles.

The relative rotation speed of the drum was estimated as [3-6].

The experimental conditions are given in Table 1.

Table 1Experimental conditions

Drum | Camera radius () | 106 mm | |

Camera length () | 100 mm | ||

Angular speed of rotation () | 0-12 rad/s | ||

Relative rotation () | 0-1.5 | ||

Grain filling of the drum chamber | Number of fractions | 1 and 2 | |

Degree of filling of the chamber with single and double fraction filling () | 0.25, 0.3, 0.35, 0.4, 0.45 and 0.5 | ||

Degree of filling of the volume of a two-fraction filling with particles of a fine fraction () | 0.4 | ||

Materials of filling | Average particle size of the coarse fraction () | 2.2 mm | |

Average particle size of the fine fraction () | (0.005-0.05)×10-3 mm | ||

Video recording of filling oscillations | Video capture frame rate | 24 FPS | |

Fill self-oscillation frequency | One faction | 1.85 Hz | |

Two factions | 2–2.18 Hz | ||

Bifurcation values of auto-oscillation parameters | Bifurcation value of relative drum rotation speed () | One faction | 0.96–1.11 |

Two factions | 0.32–0.38 | ||

Increment of the bifurcation value of the filling dilatancy () | One faction | 0.75–0.95 | |

Two factions | 0.26–0.32 | ||

The bifurcation value of the relative drum rotation speed [8] was experimentally determined, which corresponds to the minimum speed value at the beginning of self-excitation of auto-oscillations. The bifurcation value of the filling dilatancy at the beginning of self-excitation of auto-oscillations was estimated as [8], where is the minimum value of the area of the geometric figure of the filling in the flow pattern in the cross-section of the chamber during one period. The increase in the bifurcation value of the dilatancy [8] was calculated.

6. Experimental results

The loss of stability of the filling flow during the experiment was accompanied by self-excitation of auto-oscillations. The onset of self-excitation corresponded to the achievement of and . Sequential flow patterns were obtained for one period of pulsations (Table 2).

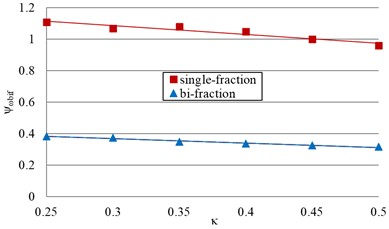

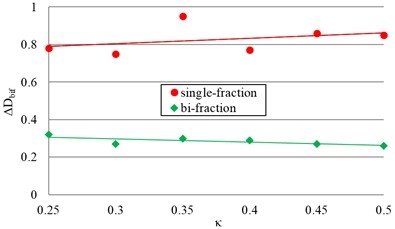

The graphs of the obtained results of experimental registration of the change in and from for single-fraction and double-fraction filling are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4Experimental dependence of the change on κ for single-fraction and be-fraction filling

a) Bifurcation value of the relative rotation speed

b) Increase in the bifurcation value of dilatancy

7. Discussion

The results of the visual analysis of the flow regimes of the granular filling of the rotating drum chamber showed the probability of the occurrence of instability of the flow in the zone of non-free fall (zone 2 Fig. 1), where the inertial mode of behavior of the filling occurs, which is in a state of shear flow (Fig. 2). This mode is characterized by a small density of the medium and a large shear velocity. The interaction of granular particles here is carried out as a result of continuous collision.

Table 2Sequential patterns of flow of filling for one period of self-oscillations at video capture frequency 24 FPS

= 0.25 | = 0.3 | = 0.35 | = 0.4 | = 0.45 | = 0.5 |

Single-fraction filling | |||||

|              |              |              |              |              |

Be-fraction filling | |||||

|            |            |            |            |            |

The results of analytical modeling revealed that the flow of the fill in the non-free fall zone in the inertial regime is stable or unstable with respect to small perturbations. Such perturbations propagate perpendicular to the shear plane, depending on the mean free path of the particles or on the dilatancy of the fill. At a relatively small dilatancy, the flow of the fill is stable, since all perturbations decay over time in the entire wavelength range. At a dilatancy greater than the bifurcation value , such a flow is unstable in a certain interval of wave numbers Eq. (10). This indicates the dependence of on the contact time during the collisions of large particles, which are damped due to the influence of the fine fraction. The value of decreases with increasing contact time relative to the mean free path time. It was found that the damping effect of the fine fraction on the interaction of large particles increases the instability of the flow (Fig. 3). The loss of stability of the flow causes self-excitation of the fill oscillations in the form of pulsations in the cross section of the chamber (Fig. 4).

The influence of the fine fraction on the bifurcation value of the relative rotation speed (Fig. 5(a)) was experimentally evaluated. The value of decreases from 0.96-1.11 for a single-fraction filling to 0.316-0.382 for a two-fraction filling. This also indicates a decrease in under the influence of the fine fraction, since with a decrease in , the fraction of the non-free fall zone decreases (Fig. 1), and therefore the value of dilatancy.

The influence of the fine fraction on the increase in the bifurcation dilatancy value was experimentally evaluated (Fig. 5(b)). The value decreases from 0.75-0.95 for single-fraction filling to 0.26-0.32 for double-fraction filling. It was also found that the decrease in under the influence of the fine fraction, approximately 1.42 times, approaches in magnitude the decrease in the filling volume due to the decrease in the free path of particles (Fig. 3). In this case, the elementary filling volume with vertices in the centers of eight neighboring particles with a packing close to cubic was considered and some increase in the free path in the longitudinal direction to the flow, compared to the transverse, was taken into account. In addition, the magnitude of the decrease in under the influence of the fine fraction, by a factor of 2.92, is quite close to the magnitude of the decrease in , by a factor of 3.02. This indicates a decrease in due to the influence of the fine fraction, which is due to the manifestation of the established dynamic effect of increased damping during the interaction of solid coarse particles by collision under the influence of soft particles of the fine fraction.

In the future, it is advisable to find out the quantitative values of the parameters of the oscillatory system when an unsteady flow occurs. This will allow establishing numerical conditions for self-excitation of pulsations of the intra-chamber filling of the drum machine for the implementation of auto-oscillating processes for processing granular materials.

8. Conclusions

The article investigates the stability of the rotating drum vibration system with a polygranular intra-chamber filling. Unstable filling behavior occurs mainly in the non-free fall zone, where an inertial flow mode with a low density of the medium and a large velocity shift and particle interaction through continuous collisions takes place. Wave processes in the filling are formalized using the dispersion equation.

The main factor of flow instability is the increase in the dilatancy of the granular medium. The increase in positive dilatancy during deformation above the bifurcation value causes the loss of flow stability. An additional factor of flow instability is the damping effect of particles of the fine fraction on the impact interaction of particles of the coarse fraction. Experimental data showed a decrease due to damping by approximately 3 times in the bifurcation values of the dilatancy increase of the two-fraction filling and the drum rotation speed at a particle size ratio of the coarse and fine fraction of about 80.

The modeling results successfully demonstrated the principle qualitative possibility of implementing self-excitation of auto-oscillations of the granular filling of the rotating drum chamber. The obtained research results are valuable for developers of innovative self-oscillating technological processes for processing granular materials in drum-type machines. Further work will be focused on clarifying the quantitative values of the dynamic parameters of the oscillatory system when an unsteady filling flow occurs, which will allow predicting the numerical conditions for implementing self-excitation of auto-oscillations.

References

-

M. Góralczyk, P. Krot, R. Zimroz, and S. Ogonowski, “Increasing energy efficiency and productivity of the comminution process in tumbling mills by indirect measurements of internal dynamics-an overview,” Energies, Vol. 13, No. 24, p. 6735, Dec. 2020, https://doi.org/10.3390/en13246735

-

H.-U. Both, “Motions of Grinding Elements in a Ball Mill,” IWF (Göttingen), Jan. 1966.

-

K. Deineka and Y. Naumenko, “Revealing the effect of decreased energy intensity of grinding in a tumbling mill during self-excitation of auto-oscillations of the intrachamber fill,” Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 6–15, Feb. 2019, https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2019.155461

-

K. Deineka and Y. Naumenko, “Establishing the effect of a decrease in power intensity of self-oscillating grinding in a tumbling mill with a reduction in an intrachamber fill,” Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, Vol. 6, No. 7 (102), pp. 43–52, Nov. 2019, https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2019.183291

-

K. Deineka and Y. Naumenko, “Establishing the effect of decreased power intensity of self-oscillatory grinding in a tumbling mill when the crushed material content in the intra-chamber fill is reduced,” Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (106), pp. 39–48, Aug. 2020, https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2020.209050

-

K. Deineka and Y. Naumenko, “Establishing the effect of a simultaneous reduction in the filling load inside a chamber and in the content of the crushed material on the energy intensity of self-oscillatory grinding in a tumbling mill,” Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, Vol. 1, No. 1 (109), pp. 77–87, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2021.224948

-

K. Y. Deineka and Y. V. Naumenko, “The tumbling mill rotation stability,” Scientific Bulletin of National Mining University, Vol. 1, pp. 60–68, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.29202/nvngu/2018-1/10

-

K. Deineka and Y. Naumenko, “Revealing the mechanism of stability loss of a two-fraction granular flow in a rotating drum,” Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (118), pp. 34–46, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2022.263097

-

G. Seiden and P. J. Thomas, “Complexity, segregation, and pattern formation in rotating-drum flows,” Reviews of Modern Physics, Vol. 83, No. 4, pp. 1323–1365, Nov. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.83.1323

-

Y. A. Berezin, K. Hutter, and L. A. Spodareva, “On stability of rapid granular shear flows,” Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 229–240, Aug. 1997, https://doi.org/10.1007/s001610050068

-

M. Alam, P. Shukla, and S. Luding, “Universality of shear-banding instability and crystallization in sheared granular fluid,” Journal of Fluid Mechanics, Vol. 615, pp. 293–321, Nov. 2008, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022112008003832

-

P. Shukla, L. Biswas, and V. K. Gupta, “Shear-banding instability in arbitrarily inelastic granular shear flows,” Physical Review E, Vol. 100, No. 3, p. 03290, Sep. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.100.032903

-

W. D. Fullmer, G. Liu, X. Yin, and C. M. Hrenya, “Clustering instabilities in sedimenting fluid-solid systems: critical assessment of kinetic-theory-based predictions using direct numerical simulation data,” Journal of Fluid Mechanics, Vol. 823, pp. 433–469, Jul. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2017.295

-

C. Varsakelis and M. V. Papalexandris, “Stability of wall bounded, shear flows of dense granular materials: the role of the Couette gap, the wall velocity and the initial concentration,” Journal of Fluid Mechanics, Vol. 791, pp. 384–413, Mar. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2016.65

-

C. Wang, Y. Wang, C. Peng, and X. Meng, “Dilatancy and compaction effects on the submerged granular column collapse,” Physics of Fluids, Vol. 29, No. 10, Oct. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4986502

-

H. Liang, S. He, Z. Chen, and W. Liu, “Modified two-phase dilatancy SPH model for saturated sand column collapse simulations,” Engineering Geology, Vol. 260, p. 105219, Oct. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105219

-

R. Li, H. Yang, G. Zheng, and Q. C. Sun, “Granular avalanches in slumping regime in a 2D rotating drum,” Powder Technology, Vol. 326, pp. 322–326, Feb. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2017.12.032

-

E. Marteau and J. E. Andrade, “A model for decoding the life cycle of granular avalanches in a rotating drum,” Acta Geotechnica, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 549–555, Dec. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-017-0609-2

-

Q. Chen et al., “Compaction and dilatancy of irregular particles avalanche flow in rotating drum operated in slumping regime,” Powder Technology, Vol. 364, pp. 1039–1048, Mar. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2019.09.047

-

X. Huang, S. Bec, and J. Colombani, “Ambivalent role of fine particles on the stability of a humid granular pile in a rotating drum,” Powder Technology, Vol. 279, pp. 254–261, Jul. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2015.04.007

-

C.-C. Liao, S.-F. Ou, S.-L. Chen, and Y.-R. Chen, “Influences of fine powder on dynamic properties and density segregation in a rotating drum,” Advanced Powder Technology, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 1702–1707, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2020.02.006

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.