Abstract

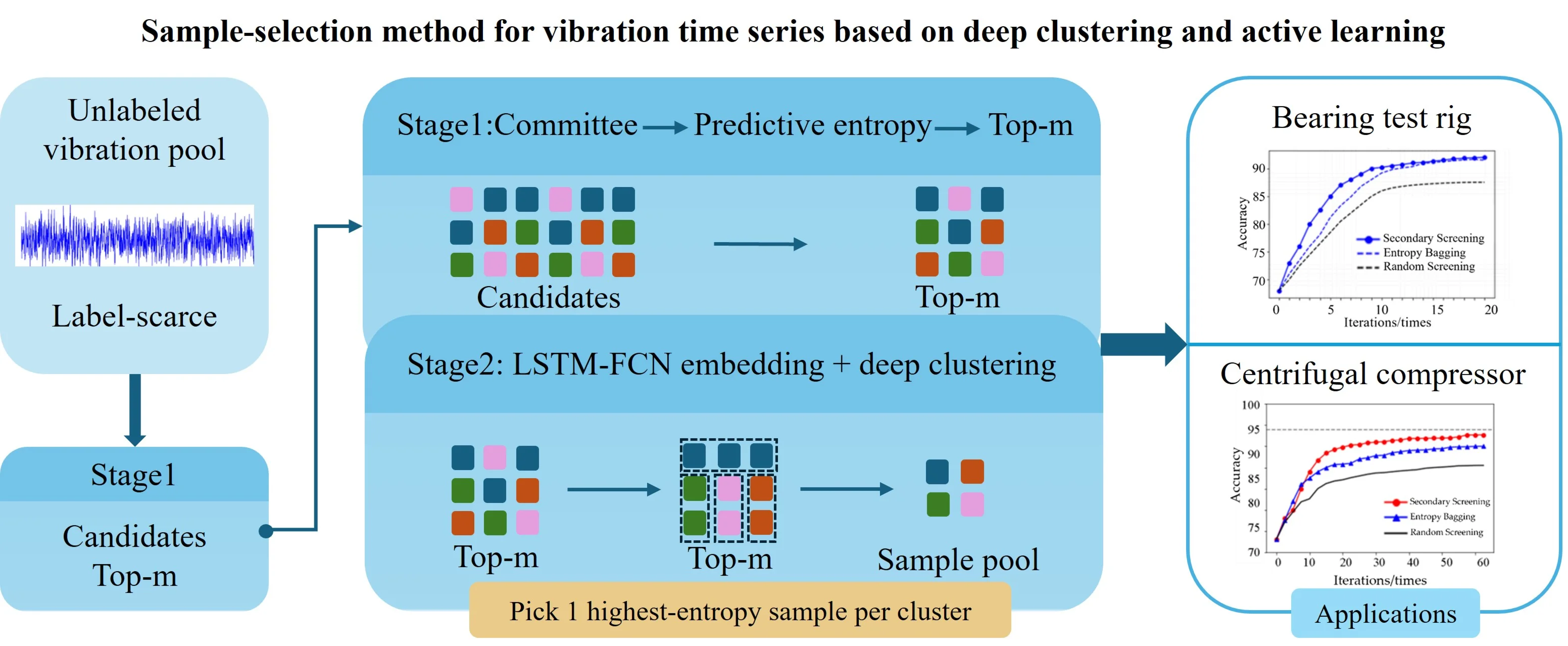

In response to the challenges posed by the substantial volume of monitoring data from rotating machinery, the considerable effort required for manual interpretation, and the scarcity of labeled fault samples, this study proposes a vibration-based anomaly-detection method that applies active learning to unlabeled vibration signals. The key novelty is a redundancy-aware batch active learning scheme, in which predictive-entropy from a committee is combined with a long short-term memory fully convolutional network (LSTM–FCN) deep-clustering module. One most representative sample is selected from each cluster to increase diversity and reduce labeling cost. The method comprises two stages: first, predictive entropy is computed for all unlabeled samples to rank uncertainty and perform an initial screening; second, a deep-clustering procedure mitigates redundancy among high-uncertainty candidates, after which the highest-entropy instance in each cluster is selected for expert labeling. Evaluations on vibration datasets from a rolling-bearing accelerated-life rig and a centrifugal-compressor rig show consistent improvements in accuracy and recognition stability over conventional clustering-based anomaly-detection methods, alleviating the dependence on scarce labeled anomalies in real-world rotating machinery monitoring.

Highlights

- A redundancy-aware batch active learning framework is proposed for vibration-based anomaly detection under severe label scarcity.

- Predictive entropy derived from a bagging committee ranks informative candidates, and LSTM–FCN embeddings enable deep clustering for diversity.

- One highest-entropy sample per cluster is queried to reduce redundancy while preserving boundary-informative samples.

- Experiments on bearing and centrifugal-compressor datasets achieve near fully supervised accuracy using only approximately 33% and 15% of labeled labels, respectively.

1. Introduction

Rotating machinery – including motors, pumps, fans, compressors, and spindle systems – constitutes a ubiquitous category of equipment in industrial facilities [1, 2]. The operational integrity of these assets hinges critically on shaft and bearing assemblies, the degradation of which can precipitate unplanned downtime and significant safety hazards [3, 4]. Consequently, vibration monitoring has established itself as a cornerstone of anomaly detection and condition monitoring, favored for its non-intrusive deployment and high sensitivity to incipient fault signatures [5, 6].

Despite advancements in data-driven methodologies, practical implementation in industrial settings is impeded by two intrinsic constraints [7]. First, equipment heterogeneity is substantial; variations in machine topology, operating modes, mounting foundations, and sensor configurations induce pronounced distribution shifts in features of vibration signals, thereby complicating robust generalization across diverse scenarios [8]. Second, high-quality labels are scarce in operational environments [9]. Anomalies are inherently rare and heterogeneous, while ground-truth annotation often necessitates expert interpretation, maintenance inspections, or disassembly – processes that are resource-intensive, costly, and frequently incompatible with strict production schedules [10]. These factors necessitate a label-efficient learning strategy capable of identifying high-value samples within a restricted annotation consumption, while simultaneously mitigating redundancy during batch selection [11].

Active learning (AL) [12] addresses these challenges by optimizing the selection of unlabeled data for annotation based on specific query strategies, thereby enhancing model performance with fewer labeled instances. In general, AL paradigms are categorized into membership query synthesis, stream-based selective sampling, and pool-based sampling [13, 14]. Membership query synthesis generates synthetic instances for annotation [15]; however, such queries frequently lack fidelity to realistic physical dynamics, limiting their applicability in industrial settings. Stream-based sampling evaluates incoming instances sequentially, a localized approach that precludes global comparison against the remaining unlabeled data, potentially resulting in suboptimal selection under fixed budgets. Conversely, pool-based sampling evaluates the entire unlabeled pool to select an informative subset [16]. This paradigm aligns optimally with practical industrial workflows where datasets are often aggregated prior to the annotation phase.

The method proposed in this study follows the pool-based active learning paradigm to select informative samples from the entire unlabeled pool. Specifically, an Entropy-based Query by Bagging (EQB) strategy is employed to estimate uncertainty for all unlabeled samples. While earlier research focused on feature selection and data mining for real-time fault diagnosis [17, 18], recent studies demonstrate the superior efficacy of deep learning architectures – specifically Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) – for anomaly detection in time-series sensor data [19]. To further enhance representativeness and diversity in batch querying, a two-stage redundancy-aware selection scheme is developed. In Stage 1, a high-uncertainty candidate set is obtained using EQB-based entropy ranking. Uniquely, Stage 2 diverges from traditional diversity strategies – which typically rely on simple geometric distances in raw feature space – by implementing deep clustering on temporal embeddings learned via an LSTM Fully Convolutional Network (LSTM-FCN). By clustering within this learned latent space, the proposed method captures the semantic temporal dependencies of vibration signals, ensuring that the selected batch maximizes fault pattern diversity rather than merely selecting statistical outliers. This design effectively reduces redundant queries while retaining informative samples situated near decision boundaries, offering a robust solution to the high-dimensional distribution shifts characteristic of industrial monitoring. Given that bearing and rotor failures account for the overwhelming majority of faults in rotating machinery, the proposed method is empirically evaluated on two vibration datasets: a rolling bearing accelerated life test and a centrifugal compressor test rig. The results demonstrate consistent improvements in detection accuracy and stability compared to entropy-based and random screening baselines, achieving these gains with substantially fewer labeled samples.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 delineates the theoretical foundations of the proposed sample screening strategy, including the EQB mechanism and the LSTM-FCN deep clustering architecture. Section 3 details the integrated redundancy-aware batch active learning framework and its two-stage screening workflow. Section 4 presents the experimental verification on rolling bearing and centrifugal compressor datasets, providing a comprehensive analysis of detection accuracy and label efficiency. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the conclusions and outlines directions for future research.

2. Active learning-based sample screening strategy for deep clustering

As rotating machinery is generally in normal operation with scarce labeled vibration monitoring data, the insufficient number of labeled samples becomes the primary factor limiting the performance of anomaly detection [20]. However, labeling by experts requires considerable time and labor costs [21]. The labeling of easily collapsible samples, which exhibit high entropy in their prediction results and a substantial volume of information, has been shown to enhance the performance of classification models. Consequently, to reduce the cost of manual labeling, the LSTM-FCN deep network is constructed as a learner, in conjunction with a deep clustering sample screening strategy based on active learning. This approach is founded on the premise that labeling easily aliased unlabeled samples can significantly enhance the model’s discriminative ability and detection accuracy.

2.1. Batch active learning

The crux of active learning algorithms lies in the selection of the active learning strategy, denoted by Q, with the more commonly employed active learning strategies comprising random sampling (RS), uncertainty sampling (US), and committee-based querying (QBC) [22]. Among these, the QBC strategy has been shown to consider the prediction results of multiple models and exhibits consistent performance [23,24]. The EQB [25] strategy is the most widely used QBC strategy. It is independent of learning algorithms, relying solely on classifier outputs. Consequently, it can be integrated with any learning algorithm.

The uncertainty of an unlabeled sample is quantified by the predictive entropy of the ensemble-averaged predictive distribution. Let denote the number of fault categories, and let denote the parameters of the committee models trained via bootstrap resampling. For each model, the class posterior is obtained from the logits by temperature-scaled softmax [26, 27]:

Averaging the posteriors across the committee yields the predictive distribution:

and the predictive entropy of is computed as:

where 10-12 is a small constant for numerical stability, and log denotes the natural logarithm (uncertainty measured in Nats). A larger indicates greater disagreement in the probability mass assigned by the committee and thus a more informative candidate for annotation. In contrast to vote entropy that relies on hard votes, Eq. (3) exploits soft probabilities and is therefore sensitive to calibration.

The committee is constructed by applying the bootstrap resampling technique to the current labeled set . Specifically, for each of the committee members, a class-stratified bootstrap subset of size is drawn with replacement (independent draws). Each member uses the same LSTM-FCN backbone but is trained from an independent random initialization on with the schedule described in Section 2.2; out-of-bag examples are used only to monitor early stopping and are never used for training. This procedure introduces the necessary diversity among the models (default 8), enabling a committee-based estimate of predictive uncertainty without additional annotation cost. Unlabeled samples are ranked by ; the integration with the deep clustering stage is described in Section 3. The computational complexity of the uncertainty calculation is O() for unlabeled samples and classes.

Traditional active learning can only select one unlabeled sample for labeling at a time and retrain the classification after each labeling. However, frequent model training is time-consuming. Batch mode active learning (BMAL) [28] addresses the inefficiency of conventional active learning sample selection by attempting to select multiple unlabeled samples simultaneously. The BMAL algorithm enhances the efficiency of active learning in the context of vast data. However, it still lacks a more effective approach to address the redundancy of information among batch samples [29]. There is currently no superior approach to address this issue. In particular, the efficacy of hard clustering in enhancing the sample representativeness is compromised by the background noise interfering with the monitoring data of mechanical equipment. Consequently, this study proposes a combination of the entropy bagging method to investigate the batch active learning algorithm, to reduce the redundancy of information among unlabeled samples of machinery and equipment monitoring data.

2.2. Deep clustering algorithm based on LSTM-FCN

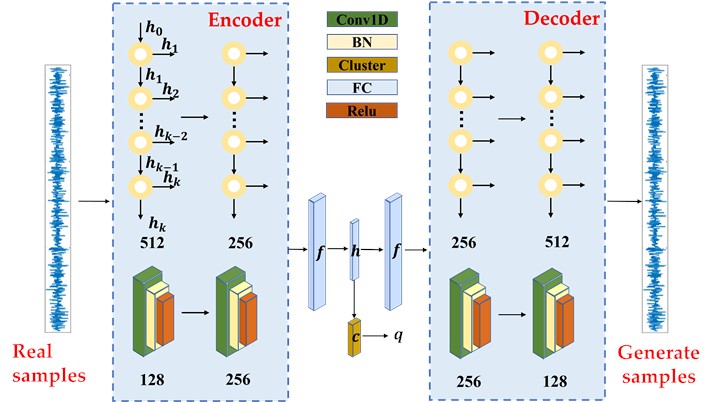

The development of active learning has resulted in the gradual integration of the BMAL algorithm with the clustering algorithm. Initially, clustering was performed on batch samples, and subsequently, a second screening was conducted between different clusters. This approach ensures that the obtained samples exhibit greater variation and are more representative [30]. Conventional clustering methodologies employed in the context of mechanical equipment monitoring signals are hindered by the presence of noise components, which impedes the attainment of precise clustering outcomes. Consequently, the extraction of time-domain data features, among other approaches, is typically used for clustering. To better adapt to the anomaly detection algorithm model and complete the automation of intelligent detection, the BMAL algorithm requires a clustering algorithm that uses the original monitoring signals and has good anti-jamming properties. This study proposes a deep clustering algorithm based on the LSTM-FCN, as shown in the network structure in Fig. 1. The deep-clustering module follows an LSTM-FCN architecture. It consists of two parallel branches. One is an FCN branch with three stacked 1-D convolutional blocks (128/256/128 filters). Each block is followed by batch normalization and ReLU. Global average pooling is applied at the end of the FCN branch. The other branch is a unidirectional LSTM with 128 hidden units. The two outputs are concatenated and projected to a -dimensional embedding used for clustering (default 10). Unless otherwise stated, optimization uses Adam (initial learning rate 10-3, weight decay 10-5), batch size 64, dropout 0.2 after the LSTM, early stopping with a patience of 10 epochs, and a maximum of 100 epochs.

Fig. 1LSTM-FCN clustering network structure.

The LSTM-FCN network is used to learn compact temporal embeddings from the vibration time series. It combines a 1-D convolutional branch to extract multi-scale local patterns with a unidirectional LSTM branch to capture long-range temporal dependencies. The outputs of the two branches are fused and then projected into a low-dimensional embedded feature of size 1×10, which is used for subsequent clustering and sample selection. Thereafter, the two components of the encoder are connected through the intermediate embedding layer. Finally, the embedded feature of each input sample is mapped to a label . The loss function of this clustering algorithm is defined as follows:

where is the reconstruction loss (L2 norm between the input and the reconstruction ); is the trade-off coefficient; and is the clustering loss defined as the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the soft assignment and the target distribution . The soft assignment is computed with a Student-t kernel (DEC-style) over the distances between the embedding and the cluster centers (degrees of freedom 1). The target distribution is obtained by sharpening (element-wise squaring followed by normalization) to emphasize confident assignments and mitigate class-imbalance. Cluster centers are initialized by -means on the embeddings and are subsequently updated jointly with the network parameters through gradient-based backpropagation. In the pre-training stage, is used to train the autoencoder and obtain a stable mapping from the data space to the embedding space. During fine-tuning, 0.1 is employed; the target distribution is refreshed periodically. Optimization uses Adam (as in Section 2.2). Training stops when the average change of between two consecutive updates of falls below a threshold .

3. Device anomaly detection via active learning of unlabeled samples

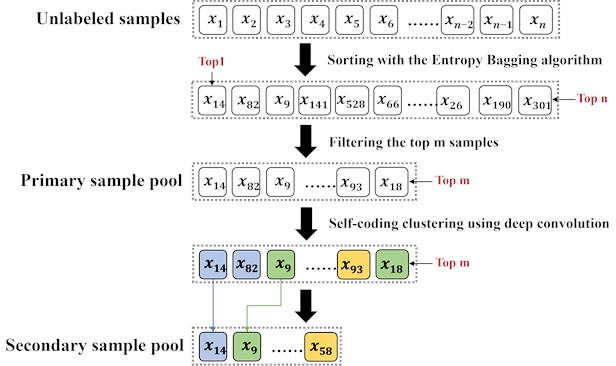

To avoid the limitations of the conventional batch active learning clustering method, particularly its vulnerability to a wild value and its insensitivity to features embedded in high-dimensional data, the batch active learning based on deep clustering (LSFM-FCN-BMAL) algorithm was developed. This algorithm was employed to enhance the diversity of high-dimensional device state data. The proposed method was initiated by employing the EQB algorithm, which undertakes first-level screening based on the entropy value of unlabeled samples. Subsequently, the algorithm clusters the screened batch samples and selects representative samples from each cluster to complete the second-level screening. The samples that emerge from this second-level screening process are both informative and representative, thus enabling effective mining of expert experience and performance enhancement of the detection model at a reduced labor cost. The specific steps of screening are as follows:

– The first filtration stage involves classifying all unlabeled samples according to the amount of information they contain. The initial stage employs the active learning algorithm to calculate the information content of all unlabeled samples. Subsequently, the unlabeled samples are arranged according to their information content, and the first samples with the most substantial information content are extracted and placed into the initial-level sample pool of active learning without being labeled first.

– The second-level screening applies the LSTM-FCN deep clustering algorithm to the first-level screening samples, grouping all candidates from the first-level sample pool into clusters. In this stage, a diversity-maximization strategy is adopted by setting the number of clusters equal to the query batch size (). This configuration ensures that exactly one representative is drawn from each cluster, thereby maximizing the structural diversity of the query batch and minimizing redundancy among candidates. Consequently, throughout all experiments, is fixed to (e.g., 5 for a batch size of 5). While the LSTM-FCN deep clustering algorithm effectively compresses the sample pool by grouping similar instances, simply selecting the cluster centroid for annotation is suboptimal, as it may ignore samples near the classification boundary. To address this, a ranking strategy is employed within each cluster. Samples are firstly ranked by the predictive-entropy score computed during the first-level screening, and then the single most informative sample (highest ) from each cluster is selected for the second-level sample pool. These selected samples are both informative and representative, and are subsequently submitted to domain experts for labeling to update the labeled set for the next iteration.

Fig. 2 illustrates the selection process of the secondary sample screening strategy. In the figure, given the observation that samples and belong to the same cluster, the second-level sample screening strategy dictates that one of these samples should be selected for inclusion in the second-level sample pool. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the selection process of the secondary sample screening strategy involves selecting sample with the highest information ranking in the same cluster, because of the limitation of sample representativeness. This is because sample has a higher information ranking than , as it is returned to the unlabeled sample pool. Conversely, sample is screened into the second-level sample pool as the sample with the highest information ranking in the other cluster. The sample with the highest information content in the cluster is filtered into the secondary sample pool.

Fig. 2Flowchart of secondary sample screening strategy

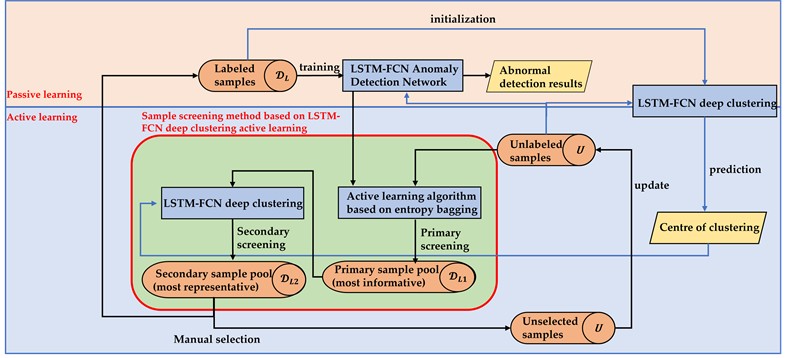

As demonstrated in the preceding analysis, the device anomaly detection method based on active learning of unlabeled vibration samples is primarily divided into two components: first, the semi-supervised learning component of sample training, and second, the active learning component of optimization, finding, labeling, and updating of unlabeled samples. The method’s flow is illustrated in Fig. 3. First, the LSTM-FCN deep clustering network is pre-trained using the labeled sample set , with the clustering loss weight set to . Subsequently, the bootstrap method is used to generate variant sub-training sets from the labeled sample set, which are then employed to train adaptive detection algorithms designed to handle labeling and signal noise. The anomaly detection models are constructed to constitute committee members, who then predict labels for all unlabeled samples, obtain labels for each sample, and calculate the entropy value of the samples accordingly. The unlabeled samples are then sorted, and the top samples with the largest entropy value are filtered to form a first-level sample pool. The samples in the first-level sample pool are then clustered using the pre-trained LSTM-FCN deep clustering algorithm, at which time the number of cluster centers is equal to the active learning batch size, and the weight of the clustering loss is set to 0.1. According to the clustering results, the samples with the largest entropy value are screened from each cluster into the second-level sample pool, and the samples in the second-level sample pool are subsequently marked by domain experts. After the labelling is completed, the newly labeled samples are added to the labeled sample set, and the updated is used to retrain the LSTM-FCN anomaly detection network. The above process is repeated until the performance of anomaly detection reaches the pre-set criteria.

Fig. 3Flowchart of the device anomaly detection method based on active learning of unlabeled samples

4. Verification analysis

In rotating machinery, shaft-system failures have been identified as major contributors to overall failures, with rotor and bearing anomalies being particularly prominent. These faults can propagate to system-level malfunctions of the equipment. Rotors and bearings are subjected to elevated loads and complex dynamic loading during operation, and common forms of failure include rotor imbalance, eccentricity, bearing wear, and inadequate lubrication. These failures frequently have a significant impact on the stability and reliability of the equipment. Therefore, to verify the feasibility and validity of the proposed method, data collection and method validation were performed on two test rigs. The first was the rolling bearing accelerated life rig of Xi’an Jiaotong University, and the second was a centrifugal compressor rig of Liaohe Engineering Co.

To provide a reproducible evaluation under realistic label-scarcity conditions, a pool-based active-learning protocol was adopted for both vibration datasets. Each dataset was split into training and test subsets. Within the training subset, only a small seed set was assumed to be labeled at the start, and all remaining training samples were treated as unlabeled. At each iteration, a fixed annotation budget of samples were selected from the unlabeled pool, and their labels were obtained from the dataset ground truth. These newly labeled samples were then added to the labeled set to update the model. For uncertainty estimation, an EQB strategy was used, where a committee of base classifiers was trained via bagging (each member trained on 75 % of the current labeled set) to produce a predictive-entropy score for each unlabeled candidate. The top- most uncertain candidates formed a first-stage pool. In the second stage, these high-uncertainty candidates were embedded by the LSTM-FCN encoder and clustered into groups, where the number of clusters was set equal to the query batch size () to enforce one selection per cluster. Within each cluster, candidates were ranked by the EQB entropy, and the single highest-entropy instance was selected for labeling, which mitigates redundancy while preserving boundary-informative samples. This query-label-retrain loop was repeated for a fixed number of iterations (20 iterations in this study), and the test-set performance was recorded after each iteration. Reported results were averaged over 10 repeated runs to reduce randomness introduced by seed selection and training stochasticity.

4.1. Rolling bearing full life dataset validation

The rolling bearing accelerated life test rig of Xi’an Jiaotong University comprises an alternating current motor, a motor speed controller, a rotating shaft, support bearings, a hydraulic loading system, and the test bearing [31]. The test bench provides adjustable working conditions, mainly the radial load and rotational speed. The hydraulic loading system applies the radial load to the bearing seat of the test bearing, while the rotational speed is set and regulated by the AC motor speed controller. The test bearing is an LDK UER204 rolling bearing, and its key parameters are listed in Table 1. The experimental settings and test information are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1Parameters of rolling bearings

Parameter name | Value |

Inner ring raceway diameter / mm | 29.30 |

Outer ring raceway diameter / mm | 39.80 |

Bearing medium diameter / mm | 34.55 |

Basic dynamic load rating / N | 12820 |

Ball diameter / mm | 7.92 |

Number of balls | 8 |

Contact angle / ° | 0 |

Ba1sic static load rating / N | 6650 |

Table 2Experimental selection of bearing related information

Parameter name | Value |

Sample size | 491 |

Basic rated life / h | 6.8-11.8 |

Actual life / h | 8.183 |

Failure location | Inner ring |

Rotational speed / rpm | 2250 |

Radial force / kN | 11 |

Sampling frequency / kHz | 25.6 |

Sampling time / s | 1.28 |

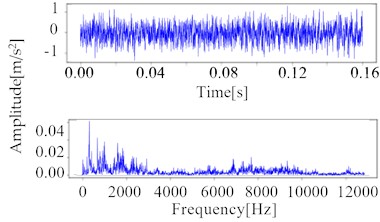

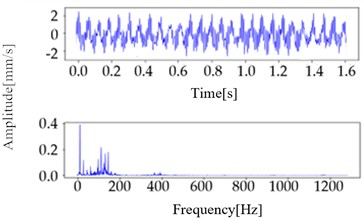

The vibration dataset under consideration contains a total of 491 samples, with each sample comprising 32,768 points. The time interval between each acquisition is 1 min, the sampling frequency is 25.6 kHz, and the length of each sample is 1.28 s. Fig. 4 shows the waveforms of the normal and abnormal samples in the time and frequency domains.

Fig. 4Time and frequency-domain waveforms

a) Normal sample after 10 min run

b) Normal sample after 100 min run

c) Abnormal sample 40 min before failure

For the active-learning evaluation, an instance-level pool was further constructed from the original acquisitions to obtain a sufficiently large candidate set under a controlled label-scarcity protocol. Specifically, an instance-level pool of 4,500 samples (4,000 normal and 500 abnormal) was constructed from the 491 acquisitions for active-learning evaluation, where “normal” instances were drawn from the early healthy stage and “abnormal” instances were drawn from the pre-failure stage. Of these, 70 % are used for training set and the remaining 30 % for testing , resulting in 2,800 normal samples and 350 abnormal samples in the training set , totaling 3,150 samples. Subsequently, a proportion of the abnormal samples is assigned labels to form the labeled sample set . Simply, there are 280 normal samples, 35 labeled abnormal samples , and the remaining samples are the unlabeled samples .

4.2. Analysis of rolling bearing dataset validation results

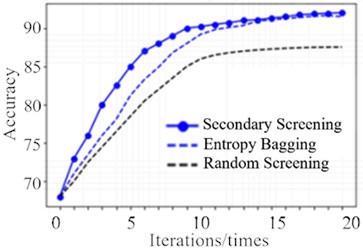

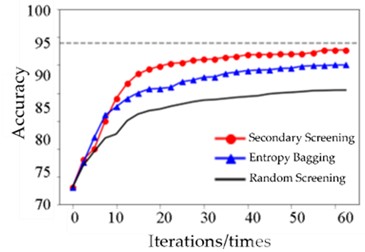

To verify the accuracy of the proposed algorithm, a secondary sample screening strategy based on LSTM-FCN deep clustering is compared with a random strategy and the state-of-the-art (SOTA) baseline, EQB. The algorithms under evaluation consists of a committee of seven adaptive noise-reduction anomaly-detection classifiers, each trained on 75 % of the samples from the training set. Here 7 is adopted as a trade-off between computational cost (which scales approximately as O()) and the ensemble diversity required for a stable predictive-entropy ranking on this dataset; larger showed diminishing returns under the same runtime/memory budget. The LSTM-FCN strategy is predicated on the assumption that the primary candidate pool is 20 and the secondary candidate pool is 5. In essence, five samples are selected for labeling in each generation, and the total number of iterations is 20. The average value is obtained by repeating the experiment 10 times. In the experimental stage, the manual expert labeling method involves querying the real labels of the samples. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5Comparison of performance improvement of sample screening methods

The accuracy of LSTM-FCN reaches 92.02 % after 20 iterations, while the accuracy obtained using all training samples to train the adaptive noise reduction classifier is 93 %. Random label selection achieves only 87.53 %, whereas the active learning algorithm attains comparable performance to the adaptive noise-reduction classifier using just 33 % of the training samples. This demonstrates the superiority of active learning in selecting samples. This finding underscores the efficacy of active learning in sample selection.

As presented in Table 3, Table 4, and Fig. 5, the EQB algorithm demonstrates enhanced accuracy compared to the original algorithm, despite employing an equivalent number of iterations, after the incorporation of the LSTM-FCN deep-clustering screening process. The LSTM-FCN algorithm differs from the original algorithm from the outset, showing a marked improvement in accuracy, with the largest increase of 4.39 % observed at the 5th iteration. The accuracy of the original EQB algorithm improves after incorporating the LSTM-FCN filtering process, likely owing to its ability to enhance balanced class sampling, ensuring that each class of samples is sampled as neutrally as possible in each selection of valuable samples. The efficacy of the algorithm becomes more evident as model evaluation is refined through iteration. As demonstrated in Tables 3-4, the model requires 7.8 % fewer training samples than the EQB algorithm to reach an accuracy of 85 %, thereby confirming the efficacy of the proposed methodology.

Table 3Accuracy of the algorithm before and after improvement for the same number of iterations

Iteration number | EQB-BMAL | LSTM-FCN-BMAL | Improvement |

5 | 78.13 % | 82.52 % | +4.39 % |

10 | 88.03 % | 90.17 % | +2.14 % |

15 | 90.9 % | 91.18 % | +0.88 % |

20 | 91.75 % | 92.02 % | +0.27 % |

Table 4Number of samples required to achieve target accuracy

Target accuracy | EQB-BMAL | LSTM-FCN-BMAL | Savings in sample size |

75 % | 223 | 212 | 11 |

76 % | 229 | 217 | 12 |

77 % | 237 | 223 | 14 |

78 % | 245 | 229 | 16 |

79 % | 251 | 235 | 16 |

80 % | 259 | 242 | 17 |

81 % | 266 | 248 | 18 |

82 % | 271 | 251 | 20 |

83 % | 272 | 254 | 18 |

84 % | 278 | 258 | 20 |

85 % | 282 | 260 | 22 |

86 % | 283 | 263 | 20 |

87 % | 285 | 267 | 18 |

To validate the robustness of the proposed two-stage selection strategy, the impact of the primary screening size and the query batch size on detection performance was investigated. First, regarding the primary pool size , values in the range of {10, 20, 30, 40} were evaluated. Results indicated that setting 10 limited the diversity of the candidate pool, causing the omission of some informative boundary samples. Conversely, increasing beyond 30 introduced excessive low-uncertainty samples into the clustering stage, which diluted the density of high-value candidates and slightly degraded the clustering purity without improving accuracy. Thus, 20 was adopted as the optimal threshold to balance candidate coverage and screening quality. Second, for the query batch size , sizes of {5, 10, 15} were tested. Smaller batches ( 5) allowed for more frequent model updates, enabling the classifier to correct its decision boundary promptly after observing a few key samples. Larger batches ( 10) reduced the retraining frequency but led to the selection of redundant information within a single batch, resulting in “diminishing returns” for annotation efforts. Therefore, 5 was selected to maximize the performance gain per labeled sample while maintaining a reasonable annotation workload.

4.3. Centrifugal compressor test bench dataset

The dataset under consideration was derived from a centrifugal compressor test bench belonging to China Liaohe Petroleum Engineering Co. The monitoring objects comprise a compressor, booster box, and motor, as well as the bearings that support these rotating bodies. The arrangement of test points on the test bench is presented in Table 5, with each point equipped with three directional sensors, positioned horizontally, vertically, and axially. These sensors can measure the vibration velocity signal in the specified directions.

Table 5Number of bench points and point names in centrifugal compressor test

Point number | Point name |

Point 1 | motor free-side bearing |

Point 2 | motor load-side bearing |

Point 3 | compressor motor-side bearing |

Point 4 | compressor non-motor side bearings |

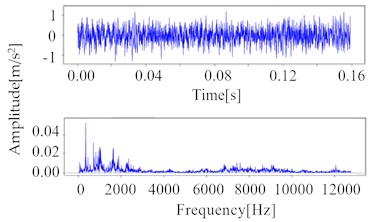

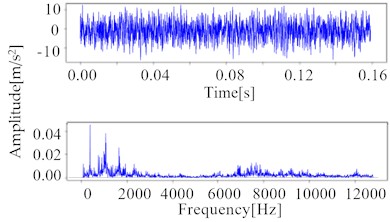

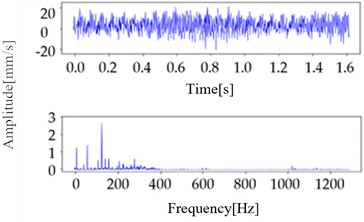

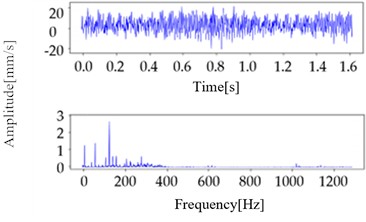

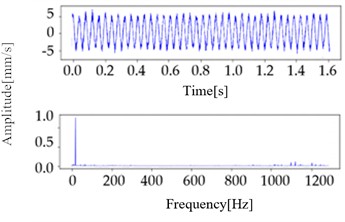

The sampling frequency was set to 2,560 Hz, the sampling time to 1.6 s, and each data set contained 4,096 sampling points. As summarized in Table 6, comprehensive data of the monitoring process are available for review. The types of data from the monitoring equipment include normal and abnormal data. Abnormal data are further classified into the following categories: unbalance, misalignment, and looseness. The time and frequency domain waveforms are illustrated in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6Time and frequency-domain waveforms

a) Normal sample

b) Misaligned sample

c) Unbalanced sample

d) Looseness sample

Given the modest number of sample points, amounting to 4,096, neither segmentation nor sliding window sampling operations are prerequisites in the data preprocessing stage. Each sample is defined as a one-dimensional vector . The dataset contains 23,560 normal samples and 5,420 abnormal samples, totaling 28,980 samples. Of these, 70 % are used for training set and the remaining 30 % for testing set , resulting in 16,492 normal samples and 3,794 abnormal samples in the training set , totaling 20,286 samples. Subsequently, a proportion of the abnormal samples is assigned labels to form the labelled sample set . Therefore, there are 1,650 normal samples, 379 labeled abnormal samples , and the remaining samples are the unlabeled samples .

Table 6Detailed information on monitoring data

Project | Detail |

Signal-to-noise ratio | Low |

Sampling frequency / kHz | 2.56 |

Motor rotation frequency / Hz | 15, 20, 25, 50 |

Failure type | Unbalance, misalignment, looseness |

4.4. Analysis of compressor dataset validation results

First, 152 misaligned anomaly samples with labels from the training set are used, along with an equal number of randomly selected normal samples, while the remaining samples are treated as unlabeled. The test set consists of 654 misaligned anomaly samples and 7,068 normal samples. For initialization, 50 normal and 50 anomalous samples are used to train the noise-containing data anomaly detection model in a supervised manner. The primary screening sample pool is set to 20, and the secondary screening sample pool is set to six. In this setup, six samples are labeled per iteration, resulting in a total of 30 iterations. The experimental phase involves querying the real labels of the samples rather than manual expert labeling. The number of anomaly detection models serving as committee members is eight. For the centrifugal-compressor dataset, 8 is used to accommodate the higher signal complexity and noise level, providing a slightly more diverse ensemble and more stable committee-averaged predictive distributions within the same experimental budget. Concurrently, active learning algorithms under various strategies are employed to ascertain the efficacy of the secondary sample screening strategy based on LSTM-FCN deep clustering. The comparison strategy includes random screening and the proposed screening strategy. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 7 and Table 7, which demonstrate that the accuracy of the secondary sample screening strategy is enhanced compared to both the random and entropy bagging strategies.

Fig. 7Comparison of the performance improvement of sample screening methods

After 30 iterations, the model achieves an anomaly detection accuracy of 93.05 % on the test set of 280 labeled samples. In comparison, the anomaly detection model based on all the training samples without the screening method achieves an accuracy of 94.73 % with 1,802 labeled samples. The anomaly detection algorithm based on the screening method achieves a comparable detection performance using 15.54 % of the labeling cost, demonstrating the superiority of the proposed method in terms of reducing labeling costs.

Table 7Accuracy of centrifugal compressor anomaly detection with different strategies for the same number of iterations

Iteration number | RS-BMAL | EQB-BMAL | LSTM-FCN-BMAL | Improvement |

5 | 77.51 % | 83 % | 84.18 % | +6.67 % |

10 | 82.91 % | 85 % | 90.44 % | +7.53 % |

15 | 84.12 % | 87 % | 91.67 % | +7.55 % |

20 | 84.68 % | 89 % | 92.50 % | +7.82 % |

25 | 85.05 % | 89 % | 92.73 % | +7.68 % |

30 | 85.66 % | 90 % | 93.05 % | +7.39 % |

To contextualize performance, the proposed framework is evaluated against a widely used state-of-the-art uncertainty-based active-learning baseline, EQB, under identical backbone, label budgets, and training schedule. As shown in Table 7 and Fig. 7, the redundancy-aware two-stage strategy attains higher final accuracy, smoother learning curves with lower variance, and faster convergence than EQB. For reference, a fully supervised LSTM-FCN trained on 100 % labeled data serves as an upper bound. The method reaches >93 % of this upper-bound accuracy while using ≈15 % of the labels, indicating strong label-efficiency for label-scarce industrial scenarios.

5. Conclusions

In rotating machinery, the large volume of vibration monitoring data from compressor equipment contrasts with the scarcity of labeled anomalies, posing a major challenge for reliable fault identification. To address this issue, this study proposes a sample-selection method for vibration time series based on deep clustering and active learning. The method combines entropy-based uncertainty and clustering-based representativeness to identify the most informative vibration segments for expert annotation, thereby reducing labeling cost and improving the efficiency of active learning.

The primary conclusions are as follows.

1) Two-stage vibration sample selection. We propose an active-learning screening strategy for vibration signals that first computes the predictive entropy of unlabeled samples to form a high-informativeness candidate pool and reduce misclassified entries in the first-level pool. To mitigate redundancy in these candidates, a deep clustering stage is introduced: an LSTM-FCN network embeds and clusters the vibration time series, and the most informative samples nearest the centroid of each cluster are selected for manual labeling. This design increases sample representativeness and diversity across operating conditions, improving the downstream anomaly-detection performance.

2) Vibration-dataset validation and effectiveness. Experiments on vibration datasets from a rolling-bearing accelerated-life rig and a centrifugal compressor rig demonstrate that the proposed method achieves higher accuracy and recognition stability than RS-BMAL, EQB-BMAL, and other conventional clustering-based screening strategies. In particular, the second-stage clustering selection produces significant improvements over random and entropy-bagging baselines. These results indicate that the proposed screening strategy effectively tackles the shortage of labeled vibration anomalies in industrial monitoring and enables more cost-efficient, reliable vibration-based condition monitoring of rotating machinery.

The future work will be extended in two directions: (i) Online stream-based active learning: batch-mode selection will be adapted to streaming by using a sliding-window extractor, drift/change-point detection to trigger model updates, and a budgeted querying policy; effectiveness will be verified on continuous runs by reporting latency per update, label budget per day, and time-to-detection. (ii) Multi-modal fusion: vibration will be fused with process variables (e.g., temperature, pressure) via late-fusion and feature-level fusion baselines, with robustness to missing sensors and ablations on fusion strategy. In addition, an adaptive choice of and based on internal validity indices and calibration will be explored, and a field pilot on the compressor line (30-day trial) is planned to quantify real-world gains in accuracy and label cost.

References

-

M. Tiboni, C. Remino, R. Bussola, and C. Amici, “A review on vibration-based condition monitoring of rotating machinery,” Applied Sciences, Vol. 12, No. 3, p. 972, Jan. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/app12030972

-

I. Misbah, C. K. M. Lee, and K. L. Keung, “Fault diagnosis in rotating machines based on transfer learning: Literature review,” Knowledge-Based Systems, Vol. 283, p. 111158, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111158

-

R. B. Randall, Vibration-Based Condition Monitoring: Industrial, Automotive and Aerospace Applications. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2021.

-

M. Hakim, A. A. B. Omran, A. N. Ahmed, M. Al-Waily, and A. Abdellatif, “A systematic review of rolling bearing fault diagnoses based on deep learning and transfer learning: Taxonomy, overview, application, open challenges, weaknesses and recommendations,” Ain Shams Engineering Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, p. 101945, Apr. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2022.101945

-

I. U. Hassan, K. Panduru, and J. Walsh, “An in-depth study of vibration sensors for condition monitoring,” Sensors, Vol. 24, No. 3, p. 740, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/s24030740

-

“Mechanical vibration-measurement and evaluation of machine vibration-Part 3: Industrial machinery with a nominal power above 15 kW and nominal speeds between 120 r/min and 15,000 r/min when measured in situ,” International Organization for Standardization, ISO 20816-3:2022, 2022.

-

S. Yao, Q. Kang, M. Zhou, M. J. Rawa, and A. Abusorrah, “A survey of transfer learning for machinery diagnostics and prognostics,” Artificial Intelligence Review, Vol. 56, No. 4, pp. 2871–2922, Aug. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-022-10230-4

-

G. Wu, T. Yan, G. Yang, H. Chai, and C. Cao, “A review on rolling bearing fault signal detection methods based on different sensors,” Sensors, Vol. 22, No. 21, p. 8330, Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/s22218330

-

D. Cacciarelli and M. Kulahci, “Active learning for data streams: a survey,” Machine Learning, Vol. 113, No. 1, pp. 185–239, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-023-06454-2

-

J. Lu, W. Wu, X. Huang, Q. Yin, K. Yang, and S. Li, “A modified active learning intelligent fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings with unbalanced samples,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, Vol. 60, p. 102397, Apr. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2024.102397

-

J. T. Ash, C. Zhang, A. Krishnamurthy, J. Langford, and A. Agarwal, “Deep batch active learning by diverse, uncertain gradient lower bounds,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. (ICLR), 2020.

-

T. Martín-Noguerol, P. López-Úbeda, F. Paulano-Godino, and A. Luna, “Manual data labeling, radiology, and artificial intelligence: It is a dirty job, but someone has to do it,” Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Vol. 116, p. 110280, Feb. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2024.110280

-

T. Lei, C. Gong, G. Chen, M. Ou, K. Yang, and J. Li, “A novel unsupervised framework for time series data anomaly detection via spectrum decomposition,” Knowledge-Based Systems, Vol. 280, p. 111002, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111002

-

F. Lachekhab, M. Benzaoui, S. A. Tadjer, A. Bensmaine, and H. Hamma, “LSTM-autoencoder deep learning model for anomaly detection in electric motor,” Energies, Vol. 17, No. 10, p. 2340, May 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/en17102340

-

R. Takezoe et al., “Deep active learning for computer vision: past and future,” APSIPA Transactions on Signal and Information Processing, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 1–38, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1561/116.00000057

-

Y. Liu et al., “Deep anomaly detection for time-series data in industrial IoT: a communication-efficient on-device federated learning approach,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, Vol. 8, No. 8, pp. 6348–6358, Apr. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/jiot.2020.3011726

-

M. Demetgul, K. Yildiz, S. Taskin, I. N. Tansel, and O. Yazicioglu, “Fault diagnosis on material handling system using feature selection and data mining techniques,” Measurement, Vol. 55, pp. 15–24, Sep. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2014.04.037

-

V. G. Böcekçi and K. Yıldız, “Investigation of data mining processing stage effect on performance in interferometric measurement system,” Acta Physica Polonica A, Vol. 131, No. 1, pp. 46–47, Jan. 2017, https://doi.org/10.12693/aphyspola.131.46

-

Z. Ma and H. Guo, “Fault diagnosis of rolling bearing under complex working conditions based on time-frequency joint feature extraction-deep learning,” Journal of Vibroengineering, Vol. 26, No. 7, pp. 1635–1652, Nov. 2024, https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2024.24238

-

J. Wang, S. Yang, Y. Liu, and G. Wen, “Deep subdomain transfer learning with spatial attention convlstm network for fault diagnosis of wheelset bearing in high-speed trains,” Machines, Vol. 11, No. 2, p. 304, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/machines11020304

-

T. Pimentel, M. Monteiro, A. Veloso, and N. Ziviani, “Deep active learning for anomaly detection,” in International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Jul. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/ijcnn48605.2020.9206769

-

J. Lim et al., “Active learning through discussion: ICAP framework for education in health professions,” BMC Medical Education, Vol. 19, No. 1, p. 477, Dec. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1901-7

-

H. Xu, L. Li, and P. Guo, “Semi-supervised active learning algorithm for SVMs based on QBC and tri-training,” Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, Vol. 12, No. 9, pp. 8809–8822, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-020-02665-w

-

P. Ren et al., “A survey of deep active learning,” ACM Computing Surveys, Vol. 54, No. 9, pp. 1–40, Dec. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1145/3472291

-

D. Tuia, F. Ratle, F. Pacifici, M. F. Kanevski, and W. J. Emery, “Active learning methods for remote sensing image classification,” IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, Vol. 47, No. 7, pp. 2218–2232, Jul. 2009, https://doi.org/10.1109/tgrs.2008.2010404

-

M. Minderer et al., “Revisiting the calibration of modern neural networks,” in 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2022.

-

M. Kull, M. Perello-Nieto, M. Kängsepp, T. S. Filho, H. Song, and P. Flach, “Beyond temperature scaling: Obtaining well-calibrated multiclass probabilities with Dirichlet calibration,” in 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Jan. 2019.

-

T. N. C. Cardoso, R. M. Silva, S. Canuto, M. M. Moro, and M. A. Gonçalves, “Ranked batch-mode active learning,” Information Sciences, Vol. 379, pp. 313–337, Feb. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2016.10.037

-

A. Kirsch, J. van Amersfoort, and Y. Gal, “BatchBALD: efficient and diverse batch acquisition for deep Bayesian active learning,” in 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Jan. 2019.

-

S. Patra and L. Bruzzone, “A cluster-assumption based batch mode active learning technique,” Pattern Recognition Letters, Vol. 33, No. 9, pp. 1042–1048, Jul. 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2012.01.015

-

B. Wang, Y. Lei, N. Li, and N. Li, “A hybrid prognostics approach for estimating remaining useful life of rolling element bearings,” IEEE Transactions on Reliability, Vol. 69, No. 1, pp. 401–412, Mar. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1109/tr.2018.2882682

About this article

This work was supported by Oil & Gas Major Project of China, grant number 2025ZD1401600.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Gang Li: methodology, validation, data curation. Xiange Hou: methodology, software, writing-original draft preparation. Qing Zhang: methodology, validation, writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.