Abstract

The strength indicators of the soil layers provided in the engineering and geological report of the construction site where the building is being erected can be used to calculate the load-bearing capability of the large-diameter bored piles constructed. However, actual testing must be used to validate the calculated results. The article presents the results of determining the load-bearing capacity of large piles in the Republic of Karakalpakstan in accordance with international testing standards. Based on the results, the pile’s limit bearing capacity was determined using the Mazurkiewicz method. Then, based on the results obtained, national and international regulatory documents were compared. In addition, the advantages and limitations of determining the load-bearing capacity of piles based on theoretical and real experiments were presented.

Highlights

- Full-scale static load testing of large-diameter bored piles (Ø800 mm, L = 30 m) was conducted for the first time in Uzbekistan under ASTM D1143M-20 conditions.

- The Mazurkiewicz method showed that the ultimate bearing capacity of the tested pile reached 10,370 kN, safely exceeding the design load of 8,630 kN.

- The functional approximation method provided a higher and more accurate estimate of pile capacity (12,000 kN), demonstrating its effectiveness compared to classical interpretation methods.

1. Introduction

Skyscraper development is currently one of the top construction priorities in Uzbekistan. Alongside this, the construction of large industrial and hydraulic structures has also begun. In such projects, it is necessary to construct large-diameter bored piles beneath the foundations to enhance the seismic resistance of buildings and to transfer the structural loads to deeper, more competent soil layers.

The soil strength parameters presented in the engineering and geological report for a construction site can serve as the basis for estimating the load-bearing capacity of the piles to be installed. Nevertheless, full-scale field testing is required to validate the calculated results and ensure structural safety [1, 2].

In the construction of high-rise, industrial, and hydraulic structures, deep pile foundations embedded in clayey soils are widely used. Under heavy loads, the additional stress on the foundation base often equals or even exceeds the pre-consolidation pressure of the soil. As a result, rheological processes in the soil become more active, and a considerable portion of the total settlement is associated with creep effects [3].

Due to limited national experience in constructing and testing large piles, the design and verification of such foundations in Uzbekistan are often carried out with the participation of foreign experts—primarily from Turkey, Iran, Ukraine, and Russia. To estimate the load-bearing capacity of these large piles, the ASTM D1143M-20 standard is generally applied, reflecting the methodological requirements of Turkish and Iranian specialists [4].

However, the practical verification of the theoretically computed pile capacity is a costly and time-consuming process. “Geofundamentproekt” LLC is one of the few geotechnical organizations in Uzbekistan that has the technical capability to perform such testing. For example, under the directive of ENTER ENGINEERING PTE. LTD., the company verified the load-bearing capacity of a large bored pile designed for a thermal power plant in the Republic of Karakalpakstan. The tested pile had a designed capacity of 8630 kN.

Moreover, State Standard 5686-2020 [5], Construction Regulations 2.02.03-98 “Pile Foundations” [6], and Building Regulations and Rules 2.02.03-85 “Pile Foundations” [7] require that not less than 0.5 % of the total number of piles at a construction site be subjected to settlement (settlement) tests to confirm the design load capacity.

Over the past several decades, the behavior of large-diameter bored piles subjected to static compressive loading has been the focus of extensive investigation worldwide. Field and numerical studies have shown that both shaft resistance and base resistance depend on soil layering and stress history [8]. International design standards increasingly highlight the importance of integrating static field testing with numerical simulation to verify the bearing capacity of deep foundations [9].

Nevertheless, in Uzbekistan, the implementation of large-scale pile testing is still limited, largely due to high testing costs and insufficient specialized laboratory and field infrastructure. Therefore, adapting the procedures recommended by Eurocode 7 (EN 1997-1: 2019) and FHWA NHI-18-042 (2018) is critically important to align national geotechnical practice with international standards.

The novelty of this research lies in performing the first full-scale verification of large-diameter bored piles (Ø 800 mm, 30 m) in Uzbekistan under ASTM D1143M-20 conditions. This study bridges the gap between national and international standards and provides new regional data for Central Asian soils. The findings align with and further support the results reported by Li et al. (2022) [10], Kim and Park (2021) [11], and Xu and Liu (2023) [12] concerning the load-transfer and deformation behavior of bored piles.

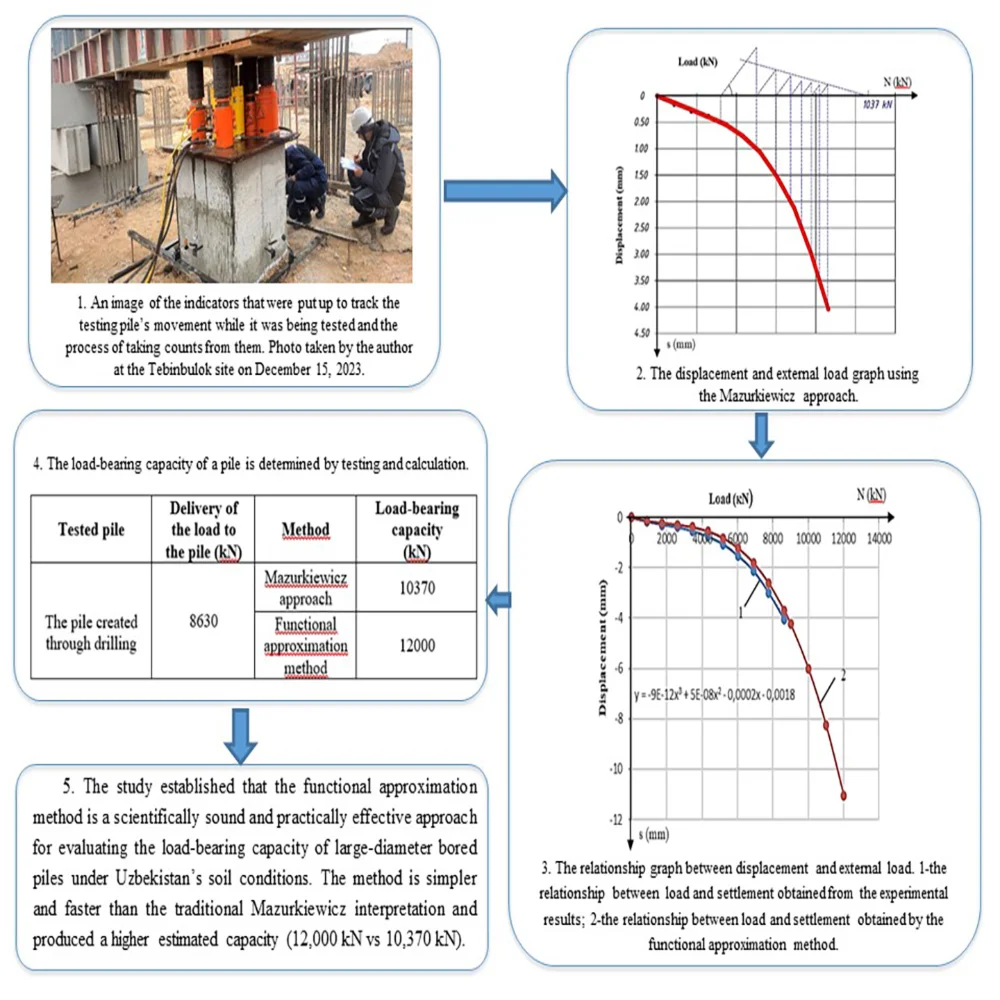

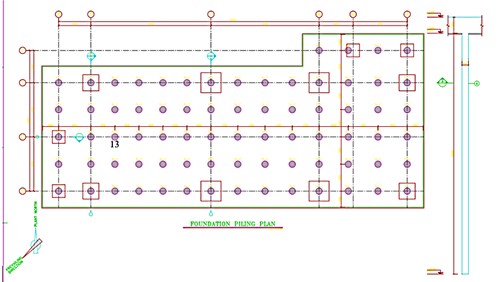

To determine the load-bearing capacity of the large-sized piles, five piles already installed at the construction site were selected. Each pile had a diameter of approximately Ø800 mm and a length of 30 m. Pile No. 13 was chosen as the test pile, while piles 8, 12, 14, and 18 served as anchor piles during the test (Fig. 1). After pile installation, a 1000×1000×1000 mm concrete cube was cast on top of the test pile to provide a stable platform for placing hydraulic jacks (Fig. 2). Twenty-eight days after concrete curing, the preparation for testing began to ensure that both the test pile and the concrete cube had achieved sufficient strength.

Fig. 1The location of the pile in the building plan under number 13, whose load-bearing capacity has been established. Photo taken by the author at the Tebinbulok site on November 1, 2023

Fig. 2A concrete cube for the test pile’s hydraulic jack placement. Photo taken by the author at the Tebinbulok site on November 13, 2023

2. Materials and methods

Preparatory work for the testing procedure. Foundation blocks were positioned on either side of the test pile to temporarily erect steel frames perpendicular to one another at the necessary height to employ anchor piles to transfer a load of 8630 kN to the test pile. Following the installation of the foundation blocks, a smaller 7 m long steel frame was placed on top of a 12 m long steel frame. The 25 pieces of Ø25 A500 class reinforcement bars, which are protruding from the 4 anchor piles around the test pile, were welded in advance to a thick-walled pipe with a diameter of Ø800 mm under two frames. A total of 18 steel plates, each measuring 6000×1500×50 mm, were positioned on a 12-meter-long steel frame to lessen the pulling stresses on the four anchor piles (Fig. 3).

Equipment and tools utilized during the testing procedure. During testing, 8630 kN of load is transferred using a total of 7 hydraulic jacks (1 of 5000 kN, 2 of 2000 kN, and 4 of 1000 kN). Two pump systems equipped with manometers rated at 100 MPa (accuracy ±1 MPa) and 60 MPa (accuracy ±0.6 MPa) are used to pressurize the hydraulic jacks. To distribute the load transmitted from the hydraulic jacks equally throughout the concrete cube’s surface, two steel plates totaling 50 mm in thickness were placed on the cube. To monitor pile settlement under the applied loads, dial indicators with a measuring range of 50 mm and an accuracy of 0.01 mm were installed on all four sides of the concrete block placed on top of the test pile. Additionally, dial indicators were installed on all four anchor piles to measure their upward displacement caused by the tensile forces of these four anchor piles.

The applied testing program followed the principles of the Static Pile Load Test Procedures proposed by the U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA NHI-18-042, 2018) [13] and was consistent with ASTM D1143M-20. Similar testing arrangements and loading sequences have been adopted in recent experimental works on deep foundations. The testing procedure complied with ASTM D1143M-20 (Standard Test Methods for Deep Foundation Elements Under Static Axial Compressive Load) and State Standard 5686-2020, “SOILS: Methods for Field Tests with Piles”.

Fig. 3A photo upon the completion of test preparation. Photo taken by the author at the Tebinbulok site on December 15, 2023

Fig. 4An image of the indicators that were put up to track the testing pile’s movement while it was being tested and the process of taking counts from them. Photo taken by the author at the Tebinbulok site on December 15, 2023

Application of load to the test pile. The loading of the drilling-constructed pile was done during the testing phase in accordance with the customer-approved program. According to ASTM and State Standards, the loads were transmitted at 10 % of 8630 kN. The deformation had to stabilize at less than 0.01 mm within an hour, or the loads at each stage had to be maintained steadily for 90 minutes and for 300 minutes during the final loading. The following Table 1 displays the loading duration.

The loading times and the magnitudes of the loads during the testing procedure are shown in Fig. 5.

Criteria for test completion. To complete the test, two primary factors are taken into account: the loads specified in the test program are transmitted step by step, and the load stage is carried out to 100 % if the settlement value does not exceed the values in the normative documents of the various countries listed in Table 2. However, the load transmission is halted and progressively decreased if the amount of settlement at a particular load stage is beyond the value limit specified in the normative standards.

Fig. 5Graph of pile loading over time during testing

Fig. 6Graph based on the Mazurkiewicz method (Birand, 2001)

Table 1Loading program

20 hour short program | |||

Loading steps (%) | Load holding times (minutes) | Loading steps (%) | Load holding times (minutes) |

0 % | 0 | 80 % | 90 |

10 % | 90 | 90 % | 90 |

20 % | 90 | 100 % | 300 |

30 % | 90 | 80 % | 15 |

40 % | 90 | 60 % | 15 |

50 % | 90 | 40 % | 15 |

60 % | 90 | 20 % | 15 |

70 % | 90 | 0 % | 30 |

Table 2According to different national standards, the crane's load-carrying capability is determined by the permissible levels (criteria) of settlement (Birand, 2001)

Definition of criterion | Criteria |

Total displacement limitation | max 25 mm (Netherlands) |

Plastic displacement limitation | 6.30 mm (AASHO) |

Plastic displacement limitation | 8.40 mm (Magnel) |

Plastic displacement limitation | 12.70 mm (Boston) |

Total displacement limitation | max 40 mm (Uzbekistan) |

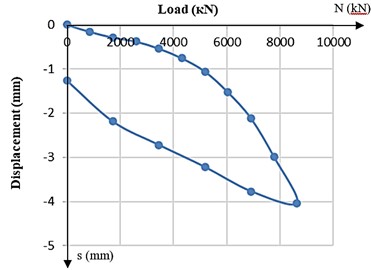

The Mazurkiewicz approach was used to examine the findings of the experiment that was performed to ascertain the pile’s load-carrying capacity. The Mazurkiewicz method is based on constructing the connection graph between the pile’s settlement and external load using a parabolic curve line extrapolation based on the results obtained after the settlement of the pile has stabilized during the testing process.

We use the Mazurkiewicz method to calculate the pile’s load-carrying capacity based on the test findings.

According to Mazurkievich’s technique, the points obtained from each loading step are plotted between the load and deformation axes to construct the initial load-deformation graph. Extrapolation is used to form a line connecting the points that have been placed. These points are used to draw an upward line parallel to the deformation axis, which intersects the load axis. A line is drawn at a 45-degree angle to the load axis from the point of intersection, and the points where the lines drawn parallel to the deformation axis intersect this line are then identified and marked. The highlighted points are used to draw a reference line, which is then extended to the load axis. The “load-bearing capability” of the pile is indicated by the value at the point where the load axis and the reference line cross (Figs. 6 and 8).

3. Results and discussion

The field test was conducted at the Tebinbulok base located in the Karauzor district of the Republic of Karakalpakstan as part of ongoing construction works. The main objective of the test was to determine the load-bearing capacity of a large-diameter bored pile constructed through drilling. The tested pile had a length of 30 m and a diameter of Ø800 mm.

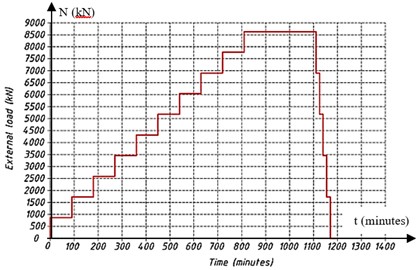

Based on the experimental results, a graph illustrating the relationship between the applied external load and the corresponding pile settlement under a maximum load of 8630 kN was developed (Fig. 7). During the testing process, the load was gradually increased in steps up to 100 % of the design value. Under the maximum load, the average reading from the dial indicators was 3.12 mm, while the residual settlement measured after complete unloading was 1.95 mm (Table 3).

According to the Mazurkiewicz interpretation method, the ultimate load-bearing capacity of the tested pile was determined to be 10370 kN, indicating that the large bored pile safely carried the design load without any signs of structural distress or instability.

The observed load-settlement behavior of the tested pile corresponds closely with findings reported in international literature. Li et al. (2022) demonstrated that the nonlinear increase in settlement beyond 70 % of the ultimate load indicates the progressive mobilization of skin friction, a trend that was also observed in this study. Similarly, Xu and Liu (2023) emphasized that cyclic or incremental loading accelerates soil creep and affects long-term settlement, confirming the necessity of applying stepwise stabilization during each loading stage.

The application of the Mazurkiewicz extrapolation method for defining the ultimate bearing capacity remains both practical and consistent with modern analytical trends. Yao and Zhang (2024) [14] recently proposed an AI-based enhancement of the Mazurkiewicz and Davisson criteria, further demonstrating their continued global relevance in pile load interpretation and design verification.

As stated in Eurocode 7 (EN 1997-1:2019) [15] and FHWA NHI-18-042 (2018) [13], the permissible settlement for large bored piles in medium-dense soils typically ranges from 25 mm to 40 mm, consistent with the criteria specified in Uzbekistan’s State Standard 5686-2020. This consistency confirms the adequacy and reliability of the adopted testing methodology and demonstrates compliance with both national and international geotechnical design standards.

Table 3Test findings

No | External load (kN) | Displacement of the pile (mm) |

0 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

1 | 863.0 | 0.16 |

2 | 1726.0 | 0.29 |

3 | 2589.0 | 0.38 |

4 | 3452.0 | 0.54 |

5 | 4315.0 | 0.76 |

6 | 5178.0 | 1.06 |

7 | 6041.0 | 1.53 |

8 | 6904.0 | 2.12 |

9 | 7767.0 | 2.99 |

10 | 8630.0 | 4.04 |

12 | 6904.0 | 3.77 |

13 | 5178.0 | 3.22 |

14 | 3452.0 | 2.72 |

15 | 1726.0 | 2.19 |

16 | 0.00 | 1.26 |

Based on the conducted experiments, the functional approximation method was considered more convenient and practical than the Mazurkiewicz method for determining the load-bearing capacity of piles. Using this approach, the ultimate bearing capacity of the pile was evaluated from the obtained experimental data. The corresponding results are presented in Table 4 and illustrated in Fig. 8.

Fig. 7The relationship graph between displacement and external load

Fig. 8The displacement and external load graph using the Mazurkiewicz approach

Table 4Test findings

No | External load (KN) | Displacement of the pile (mm) | No | External load (KN) | Displacement of the pile (mm) |

0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8 | 6904.0 | 1.813 |

1 | 863.0 | 0.136 | 9 | 7767.0 | 2.621 |

2 | 1726.0 | 0.220 | 10 | 8630.0 | 3.687 |

3 | 2589.0 | 0.291 | 12 | 9000.0 | 4.232 |

4 | 3452.0 | 0.389 | 13 | 10000.0 | 6.002 |

5 | 4315.0 | 0.551 | 14 | 11000.0 | 8.252 |

6 | 5178.0 | 0.817 | 15 | 12000.0 | 11.042 |

7 | 6041.0 | 1.225 | 8 | 6904.0 | 1.813 |

Fig. 9The relationship graph between displacement and external load: 1 – the relationship between load and settlement obtained from the experimental results; 2 – the relationship between load and settlement obtained by the functional approximation method.

Table 5The load-bearing capacity of a pile is determined by testing and calculation

Tested pile | Delivery of the load to the pile (kN) | Method | Load-bearing capacity (kN) | Method | Load-bearing capacity (kN) |

The pile created through drilling | 8630 | Mazurkiewicz approach | 10370 | Functional approximation method | 12000 |

4. Discussion

The results obtained from the full-scale static load tests of large-diameter bored piles demonstrate that the pile–soil interaction behavior in Uzbekistan’s sandy and clayey soils closely follows global geotechnical trends. The observed nonlinear load-settlement response reflects the gradual mobilization of shaft friction followed by end-bearing resistance, which corresponds to the typical deformation mechanism reported in international studies.

A critical comparison between the Mazurkiewicz and functional approximation methods reveals essential differences in their interpretative capabilities. The Mazurkiewicz approach, while classical and widely accepted, tends to underestimate the ultimate capacity due to its reliance on limited stabilized data points. Conversely, the functional approximation method provides a continuous curve representation of the entire loading history, allowing more accurate extrapolation toward the failure load. As a result, the estimated ultimate bearing capacity increased from 10,370 kN to 12,000 kN, representing an improvement of approximately 16 %.

This enhancement indicates that the functional method captures the transition between elastic and plastic behavior more effectively and minimizes local errors associated with reading fluctuations or partial settlements. The method’s computational efficiency also enables rapid analysis and is therefore suitable for both field interpretation and digital integration with monitoring systems.

The applied 20-hour loading schedule, recommended by ASTM D1143M-20, proved to be efficient for field implementation. Unlike traditional national standards requiring multi-day stabilization, this accelerated program reduces testing time by nearly 70 % without compromising reliability. This aspect is particularly beneficial for large-scale infrastructure projects, where time and cost optimization are critical.

In comparison with global research [10-12], the results confirm that the functional approximation method can serve as a viable analytical framework for the evaluation of large bored piles. The method’s adaptability to diverse soil conditions suggests its potential inclusion in updated versions of Uzbekistan’s geotechnical testing standards.

However, the present investigation was limited to one pile geometry (Ø800 mm, 30 m) and a specific soil profile. Further research should involve multiple test sites and numerical modeling to generalize the applicability of the method across different geological contexts.

5. Conclusions

The study established that the functional approximation method is a scientifically sound and practically effective approach for evaluating the load-bearing capacity of large-diameter bored piles under Uzbekistan’s soil conditions. The method is simpler and faster than the traditional Mazurkiewicz interpretation and produced a higher estimated capacity (12.000 kN vs 10.370 kN).

The testing conducted under ASTM D1143M-20 confirmed that the 20-hour program ensures reliable results while saving time and resources.

This research represents the first full-scale experimental verification of large bored piles in Uzbekistan and provides a methodological foundation for harmonizing national standards with international practices.

References

-

A. Z. Khasanov, Z. A. Khasanov, and B. Kurbanov, “Seismic isolation in sandy soils of Uzbekistan,” Menshin, Vol. 112, pp. 62–69, 2021.

-

A. Z. Khasanov, Z. A. Khasanov, and B. I. Kurbanov, “Calculation and design of vertical reinforcing elements (Vae) in soils,” European Journal of Research Development and Sustainability, Vol. 2, No. 5, pp. 39–42, 2021.

-

I. T. Mirsayapov and R. F. Sharafutdinov, “Prediction of pile foundation settlements considering rheological soil properties,” in Modern Methods of Design, Underground Construction and Reconstruction of Foundations and Structures (Conference proceedings), 2024.

-

“Standard test methods for deep foundation elements under static axial compressive load,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, ASTM D1143/D1143M-20, Jul. 2025.

-

“Soils: Methods for Field Tests with Piles,” (in Russian), Uzstandard Agency, Tashkent, State Standard 5686-2020, 2020.

-

“Construction Regulations 2.02.03-98. Pile Foundations,” (in Russian), Gosstroy of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, 1998.

-

“Building Regulations and Rules 2.02.03-85. Pile Foundations,” (in Russian), Gosstroy of USSR, Moscow, 1985.

-

K. Imai, K. Hayano, and H. Yamauchi, “Fundamental study on the acceleration of the neutralization of alkaline construction sludge using a CO2 incubator,” Soils and Foundations, Vol. 60, No. 4, pp. 800–810, Aug. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2020.05.008

-

B. H. Fellenius, “Updated design approach for pile load test interpretation,” Canadian Geotechnical Journal, Vol. 58, No. 7, pp. 1023–1036, 2021.

-

Y. Chen, W. Chen, H. Hao, and Y. Xia, “Damage evaluation of a welded beam-column joint with surface imperfections subjected to impact loads,” Engineering Structures, Vol. 261, p. 114276, Jun. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.114276

-

D. Kim and S. Park, “Static compression of bored piles in soft clay: experimental study,” Acta Geotechnica, Vol. 16, pp. 289–302, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-020-01018-4

-

H. Xu and Z. Liu, “Dynamic analysis of pile-soil interaction under cyclic load,” Geotechnical Engineering Journal, Vol. 54, No. 3, pp. 211–225, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeen.22.00241

-

“Static Pile Load Test Procedures,” Federal Highway Administration, Washington, DC, FHWA NHI-18-042, 2018.

-

Yao K. and Zhang Q., “AI-based interpretation of Mazurkiewicz and Davisson criteria,” Computers and Geotechnics, Vol. 169, p. 106255, 2024.

-

“EN 1997-1: Eurocode 7 – Geotechnical Design. Part 1: General Rules,” European Committee for Standardization, CEN, Brussels, 2019.

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.