Abstract

This paper reports on the free vibration solution of a thick plate by using three dimensional coupled thermoelastic theory. Many previously works reveal that the mechanical and thermal are coupled together, which mean that the deformation of the solid will produce temperature variation inside the solid. First, based on the three dimensional coupled thermoelastic theory, the governing equations of the thick rectangular plate for free vibration analysis are derived. Unlike the traditional first order or third order shear deformation theory with which the deformations along the thick direction are described by the deformations of the middle surface, a new form which use functions to describe the deformations along plate thick direction (the direction) is presented in this paper. Galerkin method and Laplace transform are applied to convert the governing equations into a series of first order ordinary differential equations as well as the boundary conditions to obtain the closed solution of the coupled thermoelastic rectangular plate. The Newton iterative method is applied to solve the eigenfunction. Finally, a thick plate with four edges simply supported has been investigated by using the proposed method. Eigensolutions and the damping effects of the plate with thermoelastic coupling are investigated by numerical example.

1. Introduction

Thermal variations may have great influence to mechanical characteristic of a structure. For example, the variation with respect to the temperature of clamped plates may introduce large thermal stresses in the solid since they cannot expand due to the boundary conditions. Many works introduce the thermal terms into the mechanical equations and find a lot of ways to solve them to reveal influence of the thermal effects on the structural mechanics of the solid.

Generally, there are two typical ways to describe the thermal effects to the solids: a) Thermal effects are regarded as thermal loads, which may introduce thermal stresses inside the solids, or the structure will get an initial deformation; b) The couple terms of the thermalelastic are taken into account for catching the influence between thermal variation and mechanical deformation. Hui-Shen Shen studied the postbuckling, nonlinear bending and nonlinear vibration of stiff thin films resting on an elastomeric substrate in thermal environments [1]. Thermal effects are introduced as thermal forces, and the material properties of the substrate are assumed to be temperature-dependent. Based on a higher order shear deformation plate theory, Hui-Shen Shen and Zhen-Xin Wang studied the nonlinear vibration of hybrid laminated plates containing piezoelectric layers resting on an elastic foundation in thermal environments [2]. Then, they solved the nonlinear equations by a two-step perturbation technique. Numerical results show that the temperature had little effect on the nonlinear to linear frequency ratios of the hybrid laminated plate. K. R. Jagtap et al. present the stochastic nonlinear free vibration response of elastically supported functionally graded materials plate resting on two parameters Pasternak foundation having Winkler cubic nonlinearity [3]. In their works, the material properties are assumed to be subjected to uniform and nonuniform temperature. V. Pradeep and N. Ganesan analyzed the thermal buckling and vibration behavior of multi-layer rectangular viscoelastic sandwich plates by using finite element method [4]. Numerical example of an all side clamped multi-layer viscoelastic sandwich plate illustrated the thermal buckling and critical buckling temperature phenomenon. The variation of natural frequency and loss factor with temperature was studied also. M. Amabili, S. Carra studied the nonlinear forced vibrations and postbuckling of isotropic rectangular plates by taking into account the geometric imperfections [5]. The von Kármán hypothesis was used in this paper to obtain the middle surface strains and the changes in the curvature and torsion, and the equations of motion of the plate was formulated by an energy approach. C.C. Hong introduced the first-order shear deformation theory into the generalized differential quadrature method, and deduced governing equations of magnetostrictive functionally graded material cylindrical shells for thermal vibration analysis [6]. In this paper, C. C. Hong employed the total strain energy principle to capture the varied effects of shear correction coefficient. P. Malekzadeh et al. investigated three-dimensional free vibration of functionally graded truncated conical shells subjected to thermal environment [7]. They assumed that the material properties of the functionally graded truncated conical shells were temperature dependent and graded in the radius direction, and temperature distribution inside the shell was considered as two-dimensional axisymmetric. S. J. Leea and J. N. Reddy studied the nonlinear response of laminated composite plates under uniform temperature field by using the third-order shear deformation theory, and von Kármán geometric nonlinear strain was included in the complete derivation of the governing equations also [8]. The solutions of the governing equations were obtained by using nonlinear finite element analysis. P. Ribeiro analyzed the geometrically nonlinear vibrations of linear elastic and isotropic plates under thermal effects, and the transitions from periodic to non-periodic motions were observed by numerical examples [9]. A. Allahverdizadeh et al. investigated thermal effects on the nonlinear vibration of thin circular functionally graded plates, and the von Kármán hypothesis was employed in this paper also [10]. V. Ungbhakorn, N. Wattanasakulpong derived governing equations of a functionally graded plates carrying distributed patch mass for free vibration analysis [11]. Thermal stress and the third order shear deformation theory were considered in this paper. P. Malekzadeh, S. A. Shahpari and H. R. Ziaee concentrated on the free vibration analysis of functionally graded annular plates in thermal environment by using 3D elasticity theory [12].

Thermal effects were considered as thermal loads in the works mentioned above. Many previously work reveal that the mechanical and thermal are coupled together which mean that the deformation of the solid will produce temperature variation inside the solid. On the other hand, when the heat acts on the solid, deformation will occur. N. C. Das et al. solved the general problem of the one-dimensional simultaneous equations of thermoelasticity [13]. They transform the equations into the Laplace domain directly without changing the original structure of the equations. Agostino Antonio Cannarozzi and Francesco Ubertini presented a mixed variational method for linear coupled quasi-static thermoelastic analysis [14]. They take the statement in terms of displacement, temperature, and stress as the variational support, and a finite element model for the semidiscrete analysis is developed also. S. Brischetto and E. Carrera investigated the free vibration problem of one-layered and multi-layered plates by using coupled thermomechanical theory, and they compared the free frequency values of fully coupled problems and the values of the pure mechanical problems [15]. Maenghyo Cho and Jinho Oh presented a higher order zig-zag plate theory to refine the prediction of the mechanical, thermal, and electric behaviors fully coupled [16]. By imposing top and bottom surface thermal conditions as well as interface transverse heat flux continuity conditions, the layer-dependent temperature degrees of freedom were suppressed. They used some numerical examples to demonstrate the accuracy and efficiency of the higher order zig-zag theory. M. Sinha and R. K. Bera considered heat sources in an infinite rotating media, and deduced a vector-matrix differential equation in the Laplace transform domain for a one-dimensional problem by using the fundamental equations of the generalized thermoelasticity with one relaxation parameter [17]. Then, they solved the equations by eigenvalue approach presented in literature [13]. F. A. Fazzolari and E. Carrera developed a fully coupled thermoelastic formulation by combining refined hierarchical plate models and a trigonometric Ritz method, and the thermoelastic coupling effects on the free vibration were obtained by numerical analysis [18]. Mohmed N. Allam et al. applied generalized thermoelasticity to investigate the electromagneto thermoelastic interactions in an infinite perfectly conducting body with a spherical cavity by using Laplace transform [19]. In their works, the modulus of elasticity was considered varying with temperature. Masa. Tanaka et al. presented a boundary element method for analysis of the quasistatic problems in coupled thermoelasticity [20]. Francesco Marotti de Sciarra and Maria Salerno formulated a set of thermodynamic functions in thermoelasticity without energy dissipation by using a systematic procedure based on convex/concave functions and Legendre transforms [21]. Mina Moosapour et al. derived coupled governing equations of a cantilever beam resonator with consideration of thermoelastic damping effects [22]. They discussed about the frequency shift and sensitivity change due to thermo-elastic coupling by numerical examples. Based on Kirchhoff theory, J. N. Sharma and D. Grover derived closed form expressions for the transverse vibrations of a homogenous isotropic, thermoelastic thin plate with voids [23]. They obtained the exact solutions of the free vibrations of plates. Then, they discussed about the temperature variation, frequency shifts and thermoelastic damping in the plates. M. Zhong and Y. Zhang derived a fundamental solutions and boundary integral equations of the generalized thermoelasticity with non-small temperature variation [24]. P. H. Tehrani and M. R. Eslami presented a boundary element method for harmonic analysis of a finite two-dimensional structure in dynamic coupled thermoelasticity [25]. Then, they developed this method for transient coupled thermoelasticity problems in two-dimensional finite domain [26]. Roderick and V. N. Melnik investigated the properties of discrete approximations for numerical models with coupled thermoelasticity in the stress temperature formulation [27].

Coupled free vibration of thick rectangular plate based on three-dimensional thermoelastic theory is investigated in this paper. The governing equations of the thick rectangular plate for free vibration analysis are derived by directly using 3D thermoelastic theory. In most early works, the governing equations were derived by using first order or third order shear deformation theory. With the first order or third order shear deformation theory, the deformations along the thick direction can be described by the deformations of the middle surface. Unlike most early works, we present a new form which use functions to describe the deformations along plate thick direction (the z direction). Similar to other works, the Galerkin method is employed here to obtain the approximation expression of the vibration equations. Three dimensional thermoelastic equations are converted to partial differential equations which dominated by time and thick direction in the proposed work. Then, the Laplace transform is applied to time domain and the resulting equations in the transformed field are converted to first order ordinary differential equations in state space. The exact expression of the vibration equations can be obtained when the boundary conditions are all simple supported. After solving the first order ordinary differential equations, the eigenfunction is obtained by using boundary conditions. Newton iterative method is applied to solve the eigenfunction. Finally, the eigensolutions and the damping effects vary with thermal stress coefficient and thermal expansion coefficient are investigated.

2. Governing equations of three dimensional coupled thermoelasticity

2.1. Assumptions

a) The plate which is investigated is considered as a homogeneous isotropic solid.

b) In the absence of body forces and heat flux.

c) The plate only has small deformation.

With the assumptions mentioned above, the governing equations for the dynamic coupled thermoelasticity in the time domain can be written as follows [28]:

where , and are the components of stress tensor, strain tensor and displacement vector. and are the temperature change and reference temperature respectively. , , and are the density, stress–temperature modulus, thermal conductivity coefficient and specific heat respectively. and are the Lame’s constants.

The in coupling term in Eq. (4) and heat conduction equation is nonlinear. While in small temperature change situation, and considering that , thus will lead to:

Let us denote:

Then, substituting Eq. (5) and Eq. (6) into Eq. (4) will give:

The force boundary conditions and displacement boundary conditions are written as follows:

2.2. Derivation of partial differential equations of deformation along plate thick direction

Denote , and , then substitute Eq. (2) and Eq. (3) into Eq. (1), and rewrite Eq. (1) as follows:

Substituting Eq. (2) and Eq. (3) into Eq. (4) gives:

Instead of using the first order or third order shears deformation theory, we assume that the deformations along the plate thick direction can be described by a series undetermined functions. Based on this assumption, the solution of Eq. (10) and Eq. (11) are assumed to be expressed as follows:

Quite different from early works, , , and are the to be determined functions which are employed here to describe deformations along plate thick direction of , , and respectively. , , and are known independent basis functions from the complete sets and must satisfy all the prescribed boundary conditions in the - plane.

Substitute Eq. (12) into Eq. (10) and Eq. (11), and by using weighted residual Galerkin method the following equations will be given:

For convenience, we denote , , , , , , and .

The substitution of Eq. (12), Eq. (10) and Eq. (11) into Eq. (13) will lead to:

where , and .

Notice that , , and are only dominated by coordinates and the time . Thus, we can conduct the surface integral of , , and terms without concerning about , , and . For convenience, we denote:

Substitute each term in Eq. (15) into Eq. (14) gives:

Eq. (16) are a series second order ordinary differential equations of .

2.3. Expressions in Laplace domain

Denote:

Substitute Eq. (17) into Eq. (16), then transform the resulting equations into the Laplace domain in case of zero initial conditions will have:

where is the Laplace transformation of , and:

Let and . Then, define:

Rewriting Eq. (18) in the matrix form as expressed by Eq. (19) and Eq. (20) will lead to:

Despite the undetermined variable , it is can be seen that Eq. (21) is the ordinary second order differential equation which dominated by coordinates .

2.4. Solution of the coupled thermoelastic equation

We introduce the state vectorand the matrix as specified in the following:

Then, Eq. (21) can be converted to the state space form as follows:

It is obviously that the solution of Eq. (23) can be obtained by:

where is the coordinates where the middle surface lays on, and .

Considering two typical boundary conditions as follows:

a) The temperature of surroundings and the thick plate are the same, therefore:

This means that the thick plate is in a stable and uniform temperature field.

b) There is no thermal transfer or little thermal transfer between surroundings and the thick plate, there will be:

This means that the upper and lower surface of the thick plate is insulated.

We consider the first situation (See Eq. (25)) for example, after applying the Galerkin method to the boundary condition as expressed by Eq. (25), the following equations will give:

In the same way, we transform Eq. (27) into the Laplace domain and introduce the state vector and the matrix as specified in the following:

where and are the z coordinates of the bottom and top surface of the plate. The matrix can be departed as follows:

Arbitrary block in matrix can be specified as follows:

Then, substituting of Eq. (24) into Eq. (28) will lead to:

Rewrite Eq. (31) into the matrix form will give:

where:

In order to get the nontrivial solution of Eq. (32), it is obviously that:

As the derivation process listed above, Eq. (34) is an implicit complex equation. The complex eigenfunction and the corresponding variable can be expressed as follows:

where and are the real part and the imaginary part of the complex variable respectively, while and are the real part and the imaginary part of the complex eigenfunction.

Thus, the th eigenvalue of Eq. (34) will satisfy the following equations:

Define the th thermoelastic coupling damping ratio as follows:

By substituting the th eigenvalue obtained from the solution of Eq. (36) into Eq. (33), the corresponding eigenvector will be obtained either.

Then, substitute into Eq. (24), the th natural thermoelastic coupled vibration equation of the thick plate can be obtained by applying the inverse Laplace transform to the resulting equation as follows:

3. Numerical example

Considering a four edge simply supported square plate which boundary conditions in the plane can be expressed by:

Boundary condition on the top and bottom of the plate is:

With the restriction of the boundary condition in Eq. (39), the assumed deformation and temperature variation can be expressed by:

We take 5, 5 in this numerical example.

The parameters of the square plate are listed in Table 1.

Table 1Parameters of the plate in the numerical example.

Dimension of the plate | Density / kg/m3 | Lame’s constant / GPa | Lame’s constant / GPa |

0.5 m×0.5 m | 7800 | 70 | 105 |

/ m2/s | / N/m·K | Specific heat / J/kg·K | Reference temperature / K |

18.1e5 | 5.0e6 | 879 | 1000 |

Define the dimensionless eigenvalue and the dimensionless thickness of the plate as and respectively, where and are the height and the edge length of the plate respectively.

3.1. Natural frequencies of the thermoelastic coupled thick plate

Solution of the proposed method is obtained by using the theoretical framework in the previous sections. Several eigenvalues of the plate are listed in Table 2 and Table 3 as follows.

It is can be seen from Table 2 and Table 3 that values of the real part of the dimensionless eigenvalues are almost negligible when comparing with values of the imaginary part. Thus, the natural frequency of the thick plate is almost only dominated by imaginary part of the eigenvalue. It is well known that real part of the eigenvalues represents the damping effects of the vibration system. As it can be seen from Table 3 that all real parts of the eigenvalues are negative, this illustrates that the thermolelastic coupled plate can be regarded as a damping vibration system.

Table 2Imaginary part of the eigenvalue obtained by using proposed method

Dimensionless thickness | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ |

0.05 | 0.9549 | 2.3573 | 4.6207 | 3.7260 | 5.9379 | 8.0707 |

0.10 | 1.8630 | 4.4517 | 8.3410 | 6.8405 | 10.4750 | 13.7715 |

0.15 | 2.6902 | 6.1641 | 11.008 | 9.1810 | 13.5338 | 17.3061 |

0.20 | 3.4202 | 7.5066 | 12.8610 | 10.8759 | 15.5551 | 19.4933 |

Table 3Real part of the eigenvalue obtained by using proposed method

Dimensionless thickness | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ | ͞ |

0.05 | –0.0950e-9 | –0.6896e-9 | –2.5820e-9 | –1.6976e-9 | –4.1947e-9 | –7.5511e-9 |

0.10 | –1.6972e-9 | –9.0982e-9 | –29.194e-9 | –20.315e-9 | –43.920e-9 | –70.730e-9 |

0.15 | –7.5510e-9 | –35.158e-9 | –96.015e-9 | –70.730e-9 | –134.30e-9 | –195.95e-9 |

0.20 | –20.315e-9 | –81.893e-9 | –193.30e-9 | –149.72e-9 | –253.84e-9 | –339.92e-9 |

Table 4Comparison between dimensionless natural frequencies from different method

Dimensionless thickness | Solution method | ||||||

0.05 | Proposed method | 0.9549 | 2.3573 | 2.3573 | 3.7260 | 4.6207 | 5.9379 |

FE method | 0.9541 | 2.3554 | 2.3554 | 3.7166 | 4.6257 | 5.9023 | |

Classic method | 0.9618 | 2.4061 | 2.4061 | 3.8497 | 4.8121 | 6.2558 | |

0.10 | Proposed method | 1.8630 | 4.4517 | 4.4517 | 6.8405 | 8.3410 | 10.4750 |

FE method | 1.8615 | 4.4495 | 4.4495 | 6.8279 | 8.3436 | 10.4207 | |

Classic method | 1.9236 | 4.8121 | 4.8121 | 7.6994 | 9.6242 | 12.5116 | |

0.15 | Proposed method | 2.6902 | 6.1641 | 6.1641 | 9.1810 | 11.0077 | 13.5338 |

FE method | 2.6871 | 6.1588 | 6.1588 | 9.1464 | 11.0100 | 13.4548 | |

Classic method | 2.8854 | 7.2182 | 7.2182 | 11.5491 | 14.4363 | 18.7674 | |

0.20 | Proposed method | 3.4202 | 7.5066 | 7.5066 | 12.8610 | 10.8759 | 15.5551 |

FE method | 3.4171 | 7.4998 | 7.4998 | 12.8556 | 10.8299 | 15.4639 | |

Classic method | 3.8472 | 9.6244 | 9.6244 | 15.3988 | 19.2484 | 25.0232 |

FE models of the thick plates by using solid elements has been established. Each plate is built from uniform Lagrangian solid HEX8 element of dimension 0.2×0.2×0.2. Then, mode analysis is performed with MSC.Nastran, and dimensionless natural frequencies of each FE model are obtained. We also calculate the dimensionless natural frequencies of the thick plates based on the classic plate theory. The solution based on the proposed method, FE method and the classic plate theory are named as proposed model, FE model and classic model respectively, as shown in Table 4. The dimensionless natural frequency of the proposed method is defined as . It is obviously that with the increasing of the thickness, the error of the classic plate theory becomes large, while the dimensionless natural frequencies obtained by using the proposed method match well with those obtained by using the FE method in all cases. Generally, the deformation of the HEX8 element is described by using the linear shape function. As to the thick plate, in order to approximately describe the higher order shear deformation, the plate should be divided into several elements along the thickness direction. As the result, numerous elements are required to obtain accurate result when building the FE model of the thick plate. As to the numerical example ( 0.20, for example, the thick plate is divided into five layers along the thickness direction, and the thickness of each layer is 0.2.), there are 3125 equal sized Hex8 elements, the total degree of freedom of the FE model is 3125×3 = 9375. In the proposed method, the shear deformation of the transverse section can be described exactly by Eq. (24), which is determined by solving the first order ordinary differential equation shown in Eq. (23). Since the shear deformation is given by Eq. (24), the number of the final equations is only determined by the number of the basis functions. In common cases, there are only a few number of basis functions are needed when conducting the mode analysis. Thus, comparing with the FE method, the computational efficiency of the proposed method will be greatly improved.

3.2. Damping ratio of the thermoelastic coupled thick plate

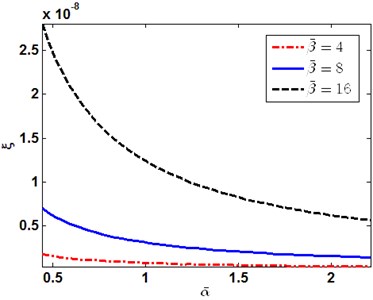

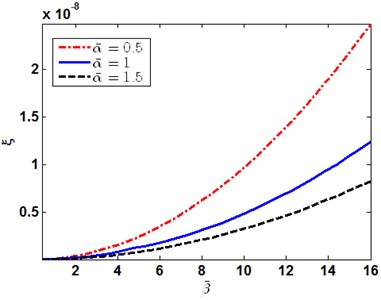

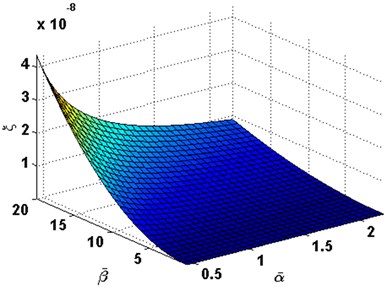

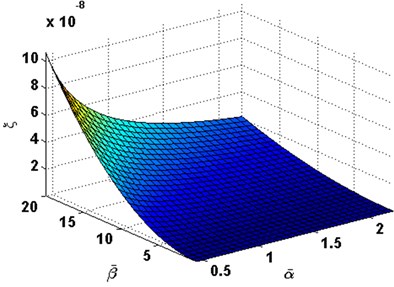

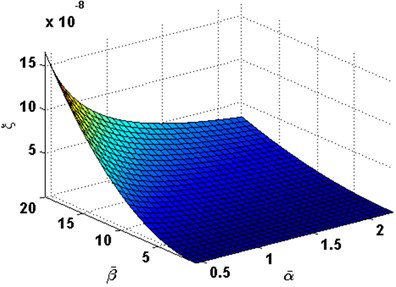

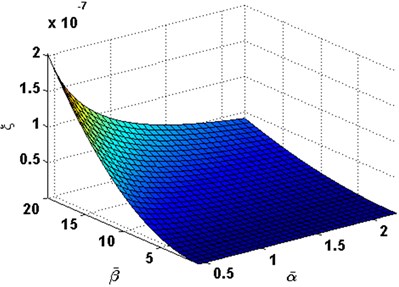

We defined , and respectively, define the dimensionless coordinates along direction as . The thermoelastic coupling damping ratio is defined as Eq. (38) (shown in Section 2.3). Fig. 1 and 2 show the first order of thermoelastic coupling damping ratio versus and . Fig. 3 to Fig. 6 illustrate the variation of the thermoelastic coupling damping ratio with and . It can be observed that with the increasing of , the thermoelastic coupling damping ratio increases too, on the contrary, with the increasing of , the thermoelastic coupling damping ratio decreases.

Fig. 1The first order of thermoelastic coupling damping ratio versus α-

Fig. 2The first order of thermoelastic coupling damping ratio versus β-

Fig. 3Damping ratio with the change of α- and β- in order (1, 1)

Fig. 4Damping ratio with the change of α- and β- in order (1, 2)

Fig. 5Damping ratio with the change of α- and β- in order (2, 2)

Fig. 6Damping ratio with the change of α- and β- in order (1, 3)

4. Conclusions

1) Vibration modes and damping effects of the thick plate have been investigated by using three dimensional thermoelastic coupled theory in this study. Galerkin method and Laplace transformation are applied to the thermoelastic coupled governing equations, as well as the boundary conditions. By using the proposed method, a series of first order ordinary differential equations governed by coordinate have been derived. Different from other works, deformation along the thick direction (the direction) is governed by the first order ordinary differential equations derived by the proposed method.

2) The shear deformation of the thick plate can be exact described by using Eq. (24). This means that the proposed method can be used to precisely solve the vibration problem of the thick plate with higher order shear deformations or complex transverse deformations.

3) By using the proposed method, closed solution of the thick plate with simply supported four edges has been deduced along with the natural frequencies and damping ratios. It can be concluded that the natural frequencies are dominated by the imaginary part of the eigenvalues. Although the real part of the eigenvalues is very small when compared with the imaginary part, all of the real part of the eigenvalues are negative, which means that the mechanical energy would be converted to thermal energy while vibration, when concerning of the thermoelastic coupling effects.

4) The proposed method is built upon three dimensional thermoelastic coupled theory only, it provide a new insight into the solution of the thick plate. The method can be expanded to deal with vibration solution of functional graded plate or other thick plate with multi-physical effects.

References

-

Shen Hui-Shen Nonlocal plate model for nonlinear analysis of thin films on elastic foundations in thermal environments. Composite Structures, Vol. 93, 2011, p. 1143-1152.

-

Shen Hui-Shen, Wang Zhen-Xin Nonlinear vibration of hybrid laminated plates resting on elastic foundations in thermal environments. Applied Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 36, 2012, p. 6275-6290.

-

Jagtap K. R., Lal Achchhe, Singh B. N. Stochastic nonlinear free vibration analysis of elastically supported functionally graded materials plate with system randomness in thermal environment. Composite Structures, Vol. 93, 2011, p. 3185-3199.

-

Pradeep V., Ganesan N. Thermal buckling and vibration behavior of multi-layer rectangular viscoelastic sandwich plates. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 310, 2008, p. 169-183.

-

Amabili M., Carra S. Thermal effects on geometrically nonlinear vibrations of rectangular plates with fixed edges. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 321, 2009, p. 936-954.

-

Hong C. C. Thermal vibration of magnetostrictive functionally graded material shells by considering the varied effects of shear correction coefficient. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 85, 2014, p. 20-29.

-

Malekzadeh P., Fiouz A. R., Sobhrouyan M. Three-dimensional free vibration of functionally graded truncated conical shells subjected to thermal environment. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping, Vol. 89, 2012, p. 210-221.

-

Leea S. J., Reddy J. N. Non-linear response of laminated composite plates under thermomechanical loading. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, Vol. 40, 2005, p. 971-985.

-

Ribeiro P. Thermally induced transitions to chaos in plate vibrations. Journal of Sound and Vibration Vol. 299, 2007, p. 314-330.

-

Allahverdizadeh A., Naei M. H., Bahrami M. Nikkhah Vibration amplitude and thermal effects on the nonlinear behavior of thin circular functionally graded plates. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Vol. 50, 2008, p. 445-454.

-

Ungbhakorn Variddhi, Wattanasakulpong Nuttawit Thermo-elastic vibration analysis of third-order shear deformable functionally graded plates with distributed patch mass under thermal environment. Applied Acoustics, Vol. 74, 2013, p. 1045-1059.

-

Malekzadeh P., Shahpari S. A., Ziaee H. R. Three-dimensional free vibration of thick functionally graded annular plates in thermal environment. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 329, 2010, p. 425-442.

-

Das N. C., Das S. N., Das B. Eigenvalue approach to thermoelasticity. Journal of Thermal Stresses, Vol. 6, Issue 1, 1983, p. 35-43.

-

Cannarozzi A. A., Ubertini F. A mixed variational method for linear coupled thermoelastic analysis. International Journal of Solids and Structures, Vol. 38, 2001, p. 717-739.

-

Brischetto S., Carrera E. Thermomechanical effect in vibration analysis of one-layered and two-layered plates. International Journal of Applied Mechanics, Vol. 3, Issue 1, 2011, p. 165-185.

-

Cho Maenghyo, Oh Jinho Higher order zig-zag theory for fully coupled thermo-electric–mechanical smart composite plates. International Journal of Solids and Structures, Vol. 41, Issues 5-6, 2004, p. 1331-1356.

-

Sinha M., Bera R. K. Eigenvalue approach to study the effect of rotation and relaxation time in generalized thermoelasticity. Computers and Mathematics with Applications, Vol. 46, 2003, p. 783-792.

-

Fazzolari Fiorenzo A., Carrera Erasmo Coupled thermoelastic effect in free vibration analysis of anisotropic multilayered plates and FGM plates by using a variable-kinematics Ritz formulation. European Journal of Mechanics A/Solids, Vol. 44, 2014, p. 157-174.

-

Allam M. N., Elsibai K. A., Abouelregal A. E. Magneto-thermoelasticity for an infinite body with a spherical cavity and variable material properties without energy dissipation. International Journal of Solids and Structures, Vol. 47, 2010, p. 2631-2638.

-

Tanaka M., Matsumoto T., Moradi M. Application of boundary element method to 3-D problems of coupled thermoelasticity. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, Vol. 16, 1995, p. 297-303.

-

Sciarra F. M., Salerno M. On thermodynamic functions in thermoelasticity without energy dissipation. European Journal of Mechanics A/Solids, Vol. 46, 2014, p. 84-95.

-

Moosapour M., Hajabasi M. A., Ehteshami H. Thermoelastic damping effect analysis in micro flexural resonator of atomic force microscopy. Applied Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 38, 2014, p. 2716-2733.

-

Sharma J. N., Grover D. Thermoelastic vibration analysis of Mems/Nems plate resonators with voids. Acta Mechanica, Vol. 223, 2012, p. 167-187.

-

Zhong M., Zhang Y. Fundamental solution and boundary integral equation of 3D coupled thermoelasticity with non-small temperature changes in Laplace transform domain. Applied Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 25, 2001, p. 347-353.

-

Tehrani P. H., Eslami M. R. Two-dimensional time-harmonic dynamic coupled thermoelasticity analysis by boundary element method formulation. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, Vol. 22, 1998, p. 245-250.

-

Tehrani P. H., Eslami M. R. BEM analysis of thermal and mechanical shock in a two-dimensional finite domain considering coupled thermoelasticity. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, Vol. 24, 2000, p. 249-257.

-

Roderick, Melnik V. N. Discrete models of coupled dynamic thermoelasticity for stress-temperature formulations. Applied Mathematics and Computation, Vol. 122, 2001, p. 107-132.

-

Nowacki W. Thermoelasticity, Second Edition. Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1986.

About this article

This paper was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11472132, No. 11602105), Fundamental Research Funds for Central University (No. NJ20160050), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20160782) and the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.