Abstract

Loess, characterized by its large pore structure and vertical joints, is prone to collapsible deformation upon moisture infiltration and significant settlement under load, threatening the stability of buildings and infrastructure. This study systematically investigates the effects of rubber particle size (10, 20, 40, and 100 mesh), content (0 %, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, and 20 % by volume), moisture content, and freeze-thaw cycles on the deformation properties of loess. This systematic investigation distinguishes itself by using waste tire rubber particles as the sole amendment to elucidate both the individual and coupled effects of these factors. Results demonstrate that incorporating rubber particles significantly reduces the compression coefficient of loess, with optimal compressibility achieved at a 5 % rubber particle content and 40 mesh particle size. The collapsibility coefficient is minimized at a 20 mesh particle size with the same 5 % content. Moisture content significantly influences deformation behavior, with both high and low levels increasing the compression and collapsibility coefficients. The study also reveals that rubber particle-loess mixtures exhibit superior freeze-thaw resistance, with smaller increases in deformation coefficients after multiple freeze-thaw cycles compared to remolded loess. The particle size and content of rubber particles are identified as the most important factors influencing the compressibility and collapsibility of loess. This research provides specific guidelines for optimizing rubber particle size and content, controlling moisture levels, and evaluating freeze-thaw impacts to enhance the engineering performance of loess. The findings offer a scientific basis for sustainable waste tire management and advance the application of rubber particles in geotechnical engineering.

Highlights

- Incorporating 5% waste tire rubber particles optimally reduces the compression coefficient of loess at 40 mesh size and minimizes the collapsibility coefficient at 20 mesh size.

- The rubber particle–loess mixture exhibits superior freeze–thaw resistance, with significantly smaller increases in deformation coefficients after multiple cycles compared to remolded loess.

- Moisture content critically influences deformation; both high and low levels increase compressibility and collapsibility coefficients, with minima observed at the optimal moisture content.

- Rubber particle size and content are identified as the most important factors governing the compressibility and collapsibility of the improved loess, respectively.

- This study provides a sustainable solution for loess stabilization using waste tires alone, offering practical guidelines for engineering in seasonal freeze–thaw regions.

1. Introduction

Loess is mainly distributed in the central and western regions of China, especially in the Loess Plateau region, and it is also widely distributed around the world [1]. Loess has large pores and vertical joints development, which make it easy to produce collapsible deformation after moisture infiltration [2], and large settlement deformation under load [3], which may cause diseases such as pavement collapse and slope instability, posing a threat to the stability of buildings and infrastructure [4].

Due to its unique geological properties, loess often faces many challenges in engineering applications, making the study of loess properties a focus of research [5, 6]. In cases where loess does not meet the needs of engineering, the properties of loess can be improved by compaction [7, 8] and the addition of lignin [9], bentonite and sodium polyacrylate [10], as well as waste tire rubber particles [11-13]. Waste tire rubber particles, with their high elasticity, low density, and environmentally friendly properties, coupled with the fact that the increasing number of waste tires resulting from China's economic development, have made the study of using waste tire rubber particles to improve the properties of loess a hot topic in recent years. Hu, et al. [14] conducted unconsolidated and undrained triaxial shear tests on rubber powder-loess using a dynamic triaxial test system to deeply explore its dynamic properties. The results show that with the increase of rubber powder content, both the dynamic shear modulus ratio and the damping ratio exhibit an increasing trend. Chai et al. [15] and Chen et al. [16] used rubber particles combined with Enzyme-Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation (EICP) technology to improve the dynamic properties of loess. The results show that the addition of appropriate rubber particles can effectively improve the pore structure of the soil, enhance the stability of the soil skeleton, and then improve the dynamic strength of the loess. Liu et al. [17] found through experiments that the addition of rubber particles significantly enhanced the unconfined compressive strength of loess. By means of compaction tests and numerical simulations, Kou et al. [18] studied the compaction properties of rubber particle-loess and showed that the addition of rubber particles can increase the California Bearing Ratio (CBR) strength of loess. As determined through triaxial consolidation undrained shear tests, Chai et al. [19] found that after adding a certain proportion of rubber powder to the backfilled loess for remolding, the cohesion decreased with the increase of rubber powder content, while the internal friction angle increased linearly with the increase of rubber powder content. Sun et al. [20] demonstrated that a composite mixture of rubber particles, lime, and fly ash can significantly reduce soil settlement and enhance the shear strength of loess. Li et al. [21] conducted one-dimensional finite compression tests and found that the compression performance of the loess mixed with rubber particles was between that of pure compacted loess and pure rubber particles. They also observed that with the increase of rubber content, the compression coefficient, elastic strain, and recovery strain were improved.

Although previous research has shown that rubber particles can effectively improve the dynamic and static properties of loess, the detailed effects of moisture content and freeze-thaw cycles on the deformation properties are not clear. Considering the distinct seasonal freeze-thaw cycles in northern China, it is essential for engineering design and soil stability evaluations to comprehend the impact of these cycles on soil mechanics and stability, because the freeze-thaw action leads to the rearrangement of soil particles and a change in the internal framework of the soil, which in turn affects its strength and overall stability. Moreover, the collapsible loess is significantly deformed when the moisture content increases, which requires special attention in practical engineering. Currently, most research focuses on mixing rubber particles with other materials to improve loess properties. However, this approach is challenging in revealing the direct effects of addition of rubber particles on the engineering properties of loess alone. Additionally, there is a lack of detailed research on the effects of the particle size and content of rubber particles on the deformation properties of loess. In contrast to most existing studies, this study focuses on loess in Inner Mongolia, considering the influence of rubber particle size (RPS), rubber particle content (RPC), moisture content (MC), and freeze-thaw action. It utilizes waste tire rubber particles as the sole improvement agent, eliminating the need for additional binders and simplifies practical application while maintaining effectiveness. This approach provides a clear understanding of their individual effects on deformation properties under freeze-thaw and moisture-varying conditions, which can significantly enrich the basic theory of rubber particle-loess improvement. This study distinguishes itself from previous work by systematically elucidating the individual and coupled effects of rubber particle size, content, moisture, and freeze-thaw cycles on the deformation properties of loess, using waste tires as the sole amendment. This approach provides novel, practical insights for sustainable ground improvement in seasonal freeze-thaw regions. The findings are expected to offer a practical and sustainable solution for loess stabilization, presenting significant value for international engineering communities dealing with seasonal freeze-thaw and collapsible soils, while also providing a scientific basis for the resource utilization of waste tires.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Material

2.1.1. Basic physical properties of loess

In this experiment, loess specimens are collected from Hohhot in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The soil, at a depth of 3 to 5 meters, is brownish-yellow in color and relatively hard and uniform in quality. The natural moisture content of the loess is 7.25 %, and the plastic limit is 15.5 %. At a cone penetration depth of 10 mm, the liquid limit is 24.7 %, and the plasticity index is 9.2. The liquid limit and plastic limit were determined using a liquid-plastic limit combined tester (LP-1000, accuracy 0.1 mm). Detailed particle composition data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1Particle size composition of loess

Range of particle size (mm) | > 2 | 2-0.5 | 0.5-0.25 | 0.25-0.075 | < 0.075 |

Percentage content (%) | 6.5 | 7.6 | 9.8 | 12.6 | 63.5 |

2.1.2. Rubber particles

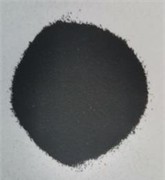

The rubber particles are made of finished rubber particles produced in Hebei Province, mainly in four particle sizes: 10 mesh, 20 mesh, 40 mesh, and 100 mesh, as shown in Fig. 1. This gradation sequence (coarse: 10-20 mesh; medium: 40 mesh; fine: 100 mesh) was chosen to cover the typical size range that previous geotechnical studies [14-16, 18, 19] have identified as most influential on the mechanical behaviour of rubber–soil mixtures. It allows a systematic investigation of the particle-size effect while keeping the experimental programme manageable. The grading curves of rubber particles of each particle size are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1Rubber particles of different particle size (Photos taken by Hai-jun Li in the Geotechnical Engineering Laboratory, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, in May 2024)

a) 10 mesh

b) 20 mesh

c) 40 mesh

d) 100 mesh

Fig. 2Grading curves of rubber particles

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Testing program

To systematically investigate the effects of rubber particle content and size on the deformation properties of loess, the rubber particles are mixed into the loess according to the volume ratio. Five different rubber particle contents (RPC = 0 %, 5 %, 10 %, 15 %, 20 %) are selected, labeled as A, B, C, D, and E, respectively. These contents are chosen based on previous studies that suggest optimal improvements in soil properties typically occur within this range [22, 23]. Additionally, four different particle sizes of rubber particles (10 mesh, 20 mesh, 40 mesh, and 100 mesh) are selected, labeled as 1, 2, 3, and 4. These sizes are selected to cover a broad range of particle sizes, as smaller and larger particles may have distinct effects on soil behavior [14, 24]. The test program is shown in Table 2.

The optimum and saturated moisture contents of rubber particle-loess are determined using the light compaction test. One third of the difference between the saturated content and optimum moisture content is calculated as the grade difference. Using the saturated moisture content as the reference, the grade difference is subtracted successively to obtain four different moisture content values, designated as proportionate moisture contents (PMC). These values are recorded in ascending order as the first, second, third, and fourth moisture contents, with the second being the optimum moisture content. This approach ensures a systematic evaluation of the soil’s behavior under varying moisture conditions, which is critical for understanding its deformation properties.

Table 2Test programme

Particle size (mesh) | Particle content (%) | ||||

0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | |

10 | A | B1 | C1 | D1 | E1 |

20 | B2 | C2 | D2 | E2 | |

40 | B3 | C3 | D3 | E3 | |

100 | B4 | C4 | D4 | E4 | |

2.2.2. Freeze-thaw cycle test

To evaluate the impact of freeze-thaw cycles on the deformation properties of rubber particle-loess, a freeze-thaw cycle test is conducted on specimens with proportionate moisture contents. The temperature range for the freeze-thaw process is set from –20 ℃ to 20 ℃, simulating the seasonal temperature variations in northern China. The number of freeze-thaw cycles (FT) is set to 0, 1, 3, 6, and 9 times, respectively. These values are chosen to represent different stages of freeze-thaw action, from no freeze-thaw to multiple cycles, which allows for a comprehensive assessment of the soil's behavior under varying degrees of freeze-thaw stress. Each freeze-thaw cycle lasts 12 hours, consisting of 6 hours for the freezing phase and 6 hours for the thawing phase, following the standard procedure for freeze-thaw testing.

Fig. 3Freeze-thaw test (Photos taken by Wen-qi Kou in the Geotechnical Engineering Laboratory, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, in June 2024)

a) Freeze-thaw specimen

b) Freeze-thaw temperature control

The freeze-thaw tests were conducted using a temperature and humidity chamber (Model: LRHS-225D-LJS, Linpin Instrument, Shanghai) with a temperature range of –70 °C to 150 °C, a humidity range of 20 % to 98 % RH, and a temperature fluctuation of ±0.5 °C, as shown in Fig. 3.

2.2.3. Deformation tests

To evaluate the deformation properties of rubber particle-loess, consolidation and collapsibility tests are conducted after freeze-thaw cycling. These tests were performed under controlled laboratory conditions: temperature is 20 °C ± 2 °C, relative humidity is 45 %±5 % and specimen is tested at natural moisture content after freeze-thaw tests. These tests are essential for understanding the compressibility and collapsibility of the soil under the following experimental conditions:

(1) Consolidation test.

The compression coefficient () was determined using a single-lever triple consolidation instrument (model: WG-Ⅲ; accuracy: ±1% full-scale) by applying stepwise loading at pressures of 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 kPa, with each pressure level maintained for 24 hours until deformation stabilized (GB/T50123-2019 Clause 17.2). These pressure levels are selected to simulate typical stress conditions encountered in engineering applications and to evaluate the soil's behavior under increasing loads.

(2) Collapsibility test.

Collapsibility tests were conducted using the same WG-Ⅲ instrument with the single-line method (GB/T50123-2019 Clause 18.2). The procedure was as follows:

a) The specimen was incrementally loaded to 50, 100, 150, and 200 kPa to assess its response to increasing loads.

b) Saturation was then conducted at 200 kPa for 24 hours to measure the collapse deformation. The final pressure of 200 kPa was applied to simulate overburden pressures typical for soil depths within 10 m.

After the experiment, visual inspection confirmed that the rubber particles were evenly distributed in the loess and maintained good adhesion with the loess matrix. The representative photos of the specimens after consolidation and collapsibility tests are shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4Photographs of rubber particle-loess specimens after testing (Photos taken by Hai-jun Li in the Geotechnical Engineering Laboratory, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot, China, in July 2024)

a) After consolidation test (RPC = 5 %, RPS = 40 mesh)

b) After collapsibility test (RPC = 5 %, RPS = 20 mesh)

3. Results

3.1. The proportionate moisture contents

Rubber particles are mixed with loess according to the specified size and content, and the light compaction test is conducted according to the Geotechnical Test Methods Standard (GB/T50123-2019) to determine the moisture content of the mixed soil specimens. The hammer used in the test weighs 2.5 kg, with a drop height of 305 mm, a hammer bottom diameter of 51 mm, a compaction cylinder inner diameter of 102 mm, and a cylinder height of 116 mm. Compaction is carried out in three layers, with 25 blows per layer. The proportionate moisture contents data from the test is shown in Table 3. According to Table 3, the addition of rubber particles to loess results in varying optimal moisture contents depending on the proportionate moisture contents, which consequently differ from the engineering properties of local Memphis loess [25].

Table 3The proportionate moisture contents

Label | PMC (%) | |||

1 | 2 (Optimal) | 3 | 4 | |

A | 11.14 | 12.20 | 13.26 | 14.32 |

B1 | 9.37 | 11.05 | 12.73 | 14.41 |

B2 | 10.15 | 11.72 | 13.29 | 14.86 |

B3 | 11.36 | 12.79 | 14.22 | 15.65 |

B4 | 12.12 | 13.51 | 14.90 | 16.29 |

C1 | 9.73 | 11.53 | 13.33 | 15.13 |

C2 | 9.71 | 11.66 | 13.61 | 15.56 |

C3 | 9.72 | 11.96 | 14.20 | 16.44 |

C4 | 10.42 | 12.44 | 14.46 | 16.48 |

D1 | 8.44 | 10.74 | 13.04 | 15.34 |

D2 | 9.14 | 11.33 | 13.52 | 15.71 |

D3 | 8.93 | 11.51 | 14.09 | 16.67 |

D4 | 8.76 | 11.60 | 14.44 | 17.28 |

E1 | 8.63 | 11.01 | 13.39 | 15.77 |

E2 | 9.35 | 11.59 | 13.83 | 16.07 |

E3 | 8.88 | 11.63 | 14.38 | 17.13 |

E4 | 8.72 | 11.67 | 14.62 | 17.57 |

Note: Index 2 indicates optimal moisture content | ||||

Based on the proportionate moisture contents, specimens are prepared and tested under light compaction conditions. The density of specimens at the optimal moisture content is found to be higher than that at other moisture contents. As shown in Table 4, for a rubber particle content of 5 % and a particle size of 40 mesh (labeled as B3), the density of the rubber particle-loess is at its maximum at the optimal moisture content, indicating that this condition results in the most compact state.

Table 4Density of soil specimen (g/cm3)

A1 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

2.011 | 1.926 | 2.003 | 2.027 | 1.997 | 1.900 | 1.938 | 1.920 | 1.861 |

D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | |

1.947 | 1.928 | 1.879 | 1.836 | 1.851 | 1.859 | 1.789 | 1.773 |

3.2. Deformation properties

Due to the fact that loess is often in a relatively dry state in practice, its moisture content is lower than the optimal moisture content. For example, the natural moisture content of loess used in this study is 7.25 %, which is lower than its optimal moisture content of 12.2 %. Therefore, in analyzing the compressibility and collapsibility of rubber particle-loess with the variation of rubber particle content, particle size, and freeze-thaw cycles, the compressibility coefficient and collapsibility coefficient corresponding to PMC values in Column 1 in Table 3 are used.

3.2.1. Compressibility

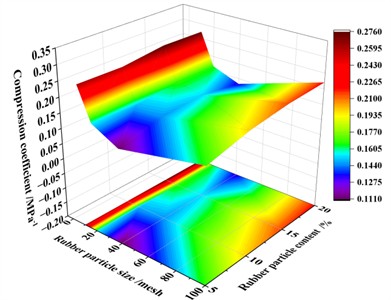

The densities presented in Table 4 represent the initial densities at the optimal moisture content for the rubber particle-loess. The specific gravity of the rubber particle-loess ranges from 2.72 to 2.56, with a difference of 0.01 from A1 to E4. Their compression coefficients under normal pressures of 100 kPa to 200 kPa are determined by consolidation tests. Fig. 5 illustrates the relationship between the compression coefficient and various influencing factors.

(1) The relationship between the compression coefficient and the rubber particle content.

Fig. 5(a) shows a non-linear relationship between the compression coefficient and the rubber particle content. The relationship between the compression coefficient and the rubber particle content varies with different rubber particle sizes. For rubber particles of 10 mesh and 20 mesh sizes, the compression coefficient initially decreases and then subsequently increases as the rubber particle content increases, but the change is relatively small. Conversely, for rubber particles of 40 mesh size, the compression coefficient first increases and then decreases. For rubber particles of 100 mesh size, the compression coefficient consistently increases with the increase in rubber particle content. Notably, the rubber particle-loess exhibits its minimum compression coefficient when the rubber particle content is 5 %.

(2) The relationship between compression coefficient and rubber particle size.

Regardless of the rubber particle content, the compression coefficient initially decreases and then increases with the increase in rubber particle size (Fig. 5(a)). The compression coefficient reaches its maximum when the particle size is 10 mesh. It subsequently decreases with increasing particle size, reaches minimum at 40 mesh, followed by 20 mesh. For particles with a size larger than 20 mesh, the compression coefficient exhibits a rapid decay. Within the range of 20 to 40 mesh, the rate of decrease gradually slows down. For particles smaller than 40 mesh, the rate of increase is extremely slow.

The reason is that when the rubber particle size is 10 mesh or 100 mesh, it is difficult to fill the small voids, because the particle size is too large, or the particle size is too small to form an effective support. This results in the rubber particle-loess not achieving the ideal dense state, and thus the compression coefficient is relatively large.

(3) The relationship between the compression coefficient and the moisture content.

Fig. 5(b) illustrates the relationship between the compression coefficient and moisture content, showing that the compression coefficient of rubber particle-loess initially decreases and then subsequently increases with increasing moisture content, reaching its minimum value at the optimal moisture content. This trend is consistent with the compressibility characteristics of loess as reported in previous studies [26]. Compared to remodeled loess (the portion in the Fig. 5(b) where the rubber particle size is 0, i.e., no rubber particles added), the addition of rubber particles significantly reduces the compression coefficient, indicating that rubber particles can diminish the compressibility of loess.

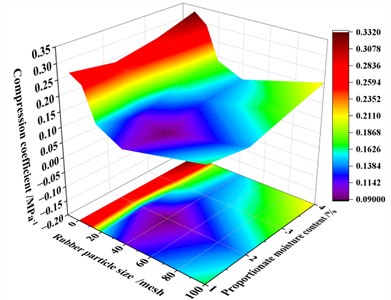

(4) The relationship between the compression coefficient and the number of freeze-thaw cycles.

Fig. 5(c) illustrates the relationship between the compression coefficient and the number of freeze-thaw cycles, showing that the compression coefficient of rubber particle-loess exhibits a gradual increase with the increasing number of freeze-thaw cycles. The initial freeze-thaw cycle exhibits a significant increase in the compression coefficient, while the rate of increase slows down after the third cycle. The compressibility behavior of rubber particle-loess is consistent with that of remolded loess. This phenomenon can be attributed to the alteration of the internal microstructure of the soil due to freeze-thaw action, which subsequently affects its compressibility. As the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases, the soil undergoes repeated volume expansion and contraction, which leads to structural degradation and an elevated compression coefficient.

Fig. 5The contour of the compression coefficient

a) Different rubber particle content and rubber particle size (FT = 0)

b) Different moisture content (FT = 0, RPC = 5 %)

c) Different number of freeze-thaw cycles (RPC = 5 %)

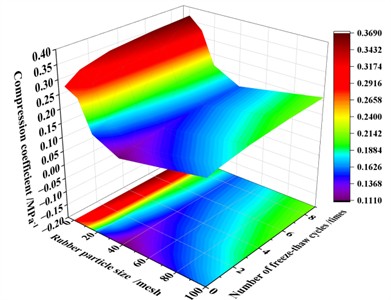

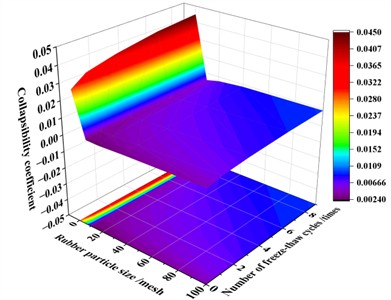

3.2.2. Collapsibility

As a critical mechanical parameter for assessing the collapsibility of loess, the collapsibility coefficient not only indicates the tendency and extent of loess collapse upon water exposure but also enhances the accuracy of predicting and evaluating loess collapsibility by correlating with influencing factors such as clay content, natural moisture content, and porosity. A thorough understanding of the factors and mechanisms governing the collapsibility coefficient can contribute to effectively evaluation and addressing of collapsible loess foundations, which is of significant importance for engineering projects in loess regions. In accordance with China’s Construction Code for Collapsible Loess Areas (GB 50025-2018), this study employed a standard pressure of 0.2 MPa to measure the collapsibility coefficient.

(1) The relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and the rubber particle content.

Fig. 6(a) illustrates the relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and the rubber particle content, showing that, regardless of the rubber particle size, the collapsibility coefficient initially increases and then decreases as rubber particle content rises. When the rubber particle content is below 10 %, the increase in the collapsibility coefficient is significant, and when it exceeds 10 %, the rate of increase decreases. The minimum collapsibility coefficient occurs at a rubber particle content of 5 %, while the maximum is observed at 15 %. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that at 5 % rubber particle content, the particles optimally distribute within the soil, effectively filling micro-pores and enhancing soil compactness, thereby significantly improving its resistance to collapsibility.

(2) The relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and the rubber particle size.

The relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and the rubber particle size varies with different rubber particle content (Fig. 6(a)). When the rubber content is 5 %, the collapsibility coefficient remains relatively constant regardless of particle size. At other rubber contents, it initially decreases and then increases as particle size increases. Consequently, the collapsibility coefficient reaches its maximum value at a particle size of 100 mesh, while it exhibits its minimum value at 20 mesh. Therefore, considering the impact on collapsibility of loess, an optimal rubber particle content of 20 % is recommended.

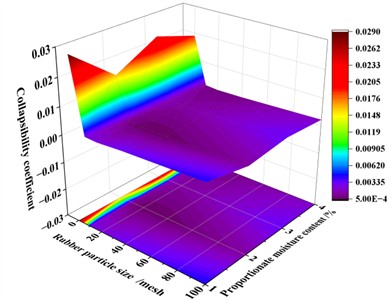

(3) The relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and the moisture content.

Fig. 6(b) illustrates the relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and moisture content, showing that the collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess exhibits a wavy pattern, and reaches its minimum at the optimal moisture content. This behavior contrasts with the negative correlation observed between the collapsibility coefficient and moisture content in untreated loess [27]. Additionally, Fig. 6(b) demonstrates that the collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess is significantly lower than that of remolded loess, which indicates that the addition of rubber particles effectively reduces the collapsibility of loess.

Fig. 6The contour of the collapsibility coefficient

a) Different rubber particle content and rubber particle size (FT = 0)

b) Different moisture content (FT = 0, RPC = 5 %)

c) Different number of freeze-thaw cycles (RPC = 5 %)

(4) The relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and the number of freeze-thaw cycles.

Fig. 6(c) illustrates the relationship between the collapsibility coefficient and the number of freeze-thaw cycles. The collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess increases overall as the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases. Notably, the collapsibility coefficient experiences a significant increase after the first freeze-thaw cycle, while the rate of increase diminishes after the third cycle. The collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess is significantly lower than that of remolded loess. The variation contour map of the collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess is relatively flat. Compared to remolded loess, the collapsibility coefficient decreases with increasing freeze-thaw cycles. Therefore, rubber particle-loess demonstrates superior resistance to the effects of freeze-thaw cycles.

4. Discussions

4.1. Deformation and compactness

The compression coefficient of soil is intrinsically linked to its degree of compactness. Within a defined pressure range, increased soil compaction leads to reduced porosity, thereby diminishing the compressibility of soil and consequently decreasing the compression coefficient. Rubber particles with different particle sizes and content can alter the pore structure of loess. Specifically, the optimal compaction of rubber particle-loess is achieved with a rubber particle content of 5 % and a particle size of 40 mesh. This results in the minimal pore volume and the smallest compression coefficient. Therefore, to enhance soil compactness and minimize compressibility, a rubber particle content of 5 % and a particle size of 40 mesh are considered optimal.

When the rubber particle content is fixed at 5 %, the collapsibility coefficient is significantly reduced for both 20 and 40 mesh sizes, with the 20 mesh blend exhibiting the lowest value. This occurs because at this optimal content, rubber particles effectively fill soil voids and stabilize the skeleton structure. Specifically, 20 mesh particles form a stable framework resisting water-induced collapse, while 40 mesh particles enhance compactness by filling finer pores. Both mechanisms mitigate structural breakdown under saturation, thereby maintaining low collapsibility regardless of particle size within this range. However, the smallest collapsibility coefficient is observed with 5 % rubber particle content and 20 mesh particle size, indicating superior collapsibility resistance under these conditions, despite not achieving the highest compaction. This suggests that the collapsibility of rubber particle-loess is influenced by factors beyond compaction, particularly the ability of water to disrupt the soil skeleton structure under external pressure [28]. Compared to 40 mesh rubber particles, 20 mesh particles form a more stable spatial skeleton structure and provide the optimal balance between pore-filling and skeleton-stabilizing effects, which helps mitigate collapse deformation.

Additionally, the superior deformability of rubber particles compared to soil particles enhances the elasticity of the rubber particle-loess system, leading to closer particle contact and occlusion, thus reducing the likelihood of compression and collapsible deformation under external loads.

4.2. Deformation and moisture content

Under optimal moisture content conditions (10.74-13.51 %, Table 3; where the specific optimal value depends on rubber particle content), the compaction effect of rubber particle-loess achieves its peak performance. The contact between soil particles becomes more intimate, and pore sizes are minimized, leading to reduced compressibility and collapsibility. Deviation from this optimal moisture content, whether higher or lower, results in decreased compactness and increased compressibility of the loess. Specifically, low moisture content leads to larger pores and a looser soil structure, facilitating water penetration and causing significant collapsible deformation. Conversely, high moisture content saturates the soil pores, reducing the likelihood of structural damage due to external water pressure [29], thereby decreasing collapsibility.

Moisture content also significantly influences the bonding between soil particles and the overall soil structure. At low moisture levels, soil particles are held together primarily by weak interparticle forces such as van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions, making the soil more susceptible to deformation under load. As moisture increases, water molecules form a thin film around the soil particles, enhancing particle bonding through capillary forces and stabilizing the soil structure. However, excessive moisture leads to water-filled pores, which can act as stress concentrators and reduce the soil's strength. The addition of rubber particles mitigates these effects by altering the pore structure and the likelihood of pore clogging, thereby improving the soil’s resistance to deformation.

4.3. Deformation and freeze-thaw cycles

When rubber particle-loess is subjected to freeze-thaw cycles, during which the water in the soil freezes and melts, this results in changes in soil volume and microstructure, ultimately leading to an increase in soil deformation [30]. The results show that after the addition of rubber particles, although the compressibility and collapsibility coefficients of the loess still increase with the number of freeze-thaw cycles, these properties of rubber particle-loess are weaker than those of remodeled loess. In particular, the increase in collapsibility coefficient is reduced with the increase of freeze-thaw cycles, which indicates that rubber particles can weaken the deformation of the loess under freeze-thaw conditions and enhance its freeze-thaw resistance. At the same time, the relationship between compression coefficient and collapsibility coefficient with the number of freeze-thaw cycles shows that the deformation of rubber particle-loess increases obviously in the first freeze-thaw cycle, and then the deformation increases slowly. Therefore, the structural damage of rubber particle-loess is serious during the first freeze-thaw cycle, and the structure tends to be stable with the increase of freeze-thaw cycles.

The high elasticity of rubber particles is a key factor in mitigating the effects of freeze-thaw cycles. During freezing, water within the soil expands, leading to increased pore pressure and potential soil structure damage. The elastic nature of rubber particles allows them to absorb and redistribute this stress, reducing the likelihood of soil particle rearrangement and structural degradation. This is supported by the experimental results, which show that the addition of rubber particles significantly reduces the increase in compression coefficient compared to remolded loess, indicating enhanced resistance to freeze-thaw-induced deformation.

The hydrophobic nature of rubber particles plays a crucial role in reducing water retention within the soil matrix. By minimizing water absorption, rubber particles limit the formation of ice crystals during freezing, which are a primary cause of soil expansion and subsequent structural damage. The reduced water content around rubber particles also decreases the risk of pore clogging and the associated increase in collapsibility upon thawing. This is evident from the experimental data, which shows that rubber particle-loess exhibits lower collapsibility coefficients even after multiple freeze-thaw cycles.

Rubber particles act as a buffer against freeze-thaw expansion by providing a flexible medium that can accommodate volume changes without causing significant structural disruption. During the freezing phase, the rubber particles’ deformability allows them to expand slightly, absorbing the volumetric increase caused by ice formation. During thawing, the rubber particles return to their original shape, preventing permanent deformation. This buffering effect is particularly important in maintaining soil stability over multiple freeze-thaw cycles, as demonstrated by the relatively stable compression and collapsibility coefficients observed in the experiments.

Although this study primarily focuses on static deformation properties, the improved elasticity and structural stability imparted by rubber particles suggest potential benefits under dynamic loading conditions (e.g., reduced permanent deformation and enhanced energy absorption). Future studies should directly investigate dynamic parameters such as resilient modulus and damping ratio to further validate these implications.

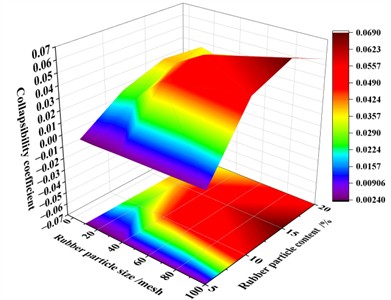

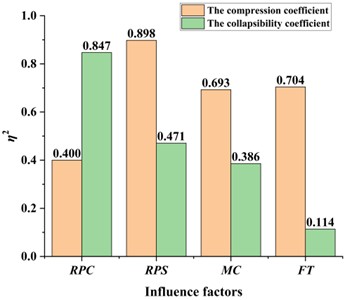

4.4. Importance analysis

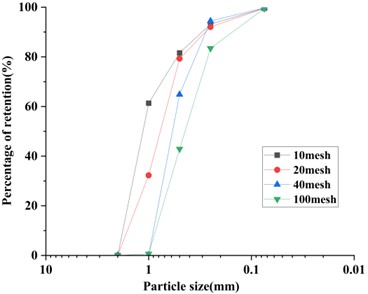

A multi-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to quantify the relative influence of rubber particle content, particle size, moisture content, and freeze-thaw cycles on the compression and collapsibility coefficients. This statistical method decomposes the total variance in the deformation coefficients into contributions attributable to individual factors, allowing for the calculation of their contribution rates (). The represents the proportion of total variance explained by each factor, providing an objective ranking of their influence. The ANOVA results are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7The contribution rates of various Influence factors

(1) The importance of rubber particle size.

The particle size of rubber particles significantly influences both the compression coefficient and the collapsibility coefficient. Fig. 7 shows that the change in particle size has a significant impact on the compression coefficient. The compression coefficient reaches its minimum value when the particle size is 40 mesh in tests, indicating that this size is particularly effective in improving the compressibility of loess. Conversely, the collapsibility coefficient is minimized at a particle size of 20 mesh, indicating that the particle can enhance the anti-collapsibility of loess more effectively. Therefore, the particle size of rubber particles is a key factor influenceing the compressibility and collapsibility of loess.

(2) The importance of rubber particle content.

Fig. 7 shows that the rubber particle content has the highest importance for the coefficient of collapsibility, indicating that it is the core factor influencing the collapsibility of loess. Reasonable control of the content can significantly reduce the collapsibility of loess. In contrast, the influence of rubber particle content on the compression coefficient is relatively small, but it still has a certain regulatory effect.

(3) The importance of moisture content.

The experimental results indicate that when the moisture content reaches its optimal value, the compressibility and collapsibility of loess are minimized. Conversely, deviations from the optimal moisture content, whether too high or too low, lead to increased values of both the compression coefficient and the collapsibility coefficient. Fig. 7 shows that the moisture content has a significant impact on both the compressibility coefficient and the collapsibility coefficient, which is consistent with the experimental results. It indicates that changes in moisture content directly influence the mechanical properties of loess, and controlling the moisture content is a crucial step in ensuring the effectiveness of the improvement.

(4) The importance of the number of freeze-thaw cycles.

The experimental results show that as the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases, the compression coefficient gradually rises, but its increase tends to stabilize after three freeze-thaw cycles. In contrast, the collapsibility coefficient remains at a low level even after multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Fig. 7 indicates that the number of freeze-thaw cycles has a significant effect on the compression coefficient but a relatively minor effect on the collapsibility coefficient, which is consistent with the experimental results.

In summary, the particle size and content of rubber particles are the most important factors affecting the compressibility coefficient and collapsibility coefficient of loess. Specifically, particle size has a more significant impact on compressibility, while content has a more critical impact on collapsibility. Additionally, moisture content significantly influences the compressibility and collapsibility of loess and is an important factor in ensuring the improvement effect. The number of freeze-thaw cycles has a certain impact on compressibility but a relatively minor effect on collapsibility. The addition of rubber particles significantly enhances the freeze-thaw resistance of improved loess. Therefore, in the improvement of loess properties, priority should be given to the rational selection of rubber particle size and control of content, while also paying attention to controlling the moisture content of loess and evaluating the potential impact of freeze-thaw cycles on the improvement effect.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, the deformation properties of loess in Inner Mongolia mixed with waste tire rubber particles of different particle sizes and contents are studied. The research results indicate that:

1) The addition of rubber particles significantly decreases the compression coefficient and collapsibility coefficient of loess, indicating a notable improvement in compressibility and collapsibility of loess. Experimental results demonstrate that at an optimal rubber particle content of 5 % and a particle size of 40 mesh, the compression coefficient reaches its minimum, achieving the best compactness. However, when the particle size is adjusted to 20 mesh at the same 5 % content, the collapsibility coefficient is minimized, suggesting that the lowest collapsibility does not necessarily occur in the most compact state.

2) For identical rubber particle content and size, the compressibility and collapsibility of rubber particle-loess are minimized at optimal moisture content. Both higher and lower moisture content increase these coefficients, highlighting the significant influence of moisture content on deformation behavior.

3) The compression coefficient and collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess under freeze-thaw cycles are smaller than those of remolded loess. The addition of rubber particles diminishes the deformation of loess during freeze-thaw cycles. With the increase of freeze-thaw cycles, the compression coefficient and collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess gradually increase. Notably, the increase in the compression coefficient of rubber particle loess with the number of freeze-thaw cycles is basically equivalent to that of remolded loess. Specifically, the first freeze-thaw cycle has a significant effect on compressibility, while the influence diminishes after the third cycle. After three freeze-thaw cycles, the increase in the collapsibility coefficient of rubber particle-loess is less significant compared to remolded loess. The addition of rubber particles enhances the freeze-thaw resistance of loess.

4) The particle size and content of rubber particles are the most important factors affecting the compressibility and collapsibility of loess. Moisture content and the number of freeze-thaw cycles also significantly influence these properties. Therefore, optimizing rubber particle size and content, controlling moisture content, and evaluating the impact of freeze-thaw cycles are crucial for enhancing the engineering performance of loess.

5) This study provides practical insights for engineering applications in loess regions by demonstrating how waste tire rubber particles can be effectively utilized to enhance the deformation properties of loess. The findings offer guidance for optimizing rubber particle size and content, controlling moisture levels, and improving soil stability under freeze-thaw conditions, which are critical for infrastructure development such as road construction, slope stabilization, and foundation engineering in cold regions. This research not only supports sustainable waste management practices but also advances the application of rubber particles in geotechnical engineering.

Future research could further examine the dynamic deformation behavior under traffic or seismic loads, including resilient modulus and damping ratio, and explore the long-term performance and durability of rubber particle-loess mixtures under arid climates, high-moisture environments, and extreme temperature variations. Additionally, investigating the potential of combining rubber particles with other soil improvement materials could enhance the sustainability and performance of infrastructure in loess regions.

References

-

F. Wang, D. Liu, F. Cheng, Y. Huo, Z. Bai, and S. Xu, “Immersion test and collapsibility evaluation of deep loess site,” (in Chinese), Hydro-Science and Engineering, Vol. 5, pp. 131–138, 2023.

-

J. Liu, T. Wei, H. Hui, and Y. Jiang, “Analysis of soaking deformation characteristics of large-thickness discontinuous collapsible loess,” (in Chinese), Journal of Geomechanics, Vol. 30, pp. 921–932, 2024.

-

M. Zhou, “Research on the key technology of uneven settlement control of collapsible loess subgrade under complex conditions,” (in Chinese), Construction and Design for Project, Vol. 21, pp. 48–50, 2023.

-

Y. Wen, “Research on uneven settlement control measure of collapsible loess subgrade under complex condition,” (in Chinese), Engineering Technology Research, Vol. 9, No. 19, pp. 147–149, 2024, https://doi.org/10.19537/j.cnki.2096-2789.2024.19.048

-

L. Li, J. Wang, Q. Gu, D. Zhang, and S. Jiao, “The influence of moisture-rich interlayers in palesol strata on the collapsibility of loess terrain,” (in Chinese), Journal of Northwest University (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 72–83, 2024, https://doi.org/10.16152/j.cnki.xdxbzr.2024-01-009

-

Z. Zhang and X. Yang, “Measurement method of collapse coefficient and initial pressure of collapsible loess in helinger new area,” (in Chinese), Journal of Inner Mongolia University of Technology (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 42, No. 6, pp. 555–560, 2023.

-

L. Liu, “Research on the application of deep dynamic compaction technology inside the hole in the treatment of collapsible loess,” (in Chinese), Value Engineering, Vol. 43, No. 32, pp. 47–49, 2024.

-

X. Hou, Y. Wang, and C. Hu, “Study on moisture migration pattern and permeability of collapsible loess foundation under dynamic compaction,” (in Chinese), Journal of Taiyuan University of Technology, pp. 1–15, 2024.

-

W. Liu, J. Lian, and J. Zhao, “Collapsibility test on the loess inhibited by lignin,” (in Chinese), China Earthquake Engineering Journal, Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 557–565, 2024, https://doi.org/10.20000/j.1000-0844.20220717003

-

M. Wang and Z. Wang, “Experimental study on improving collapsible loess with a mixture of bentonite and sodium polyacrylate,” (in Chinese), Aging and Application of Synthetic Materials, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 79–82, 2023, https://doi.org/10.16584/j.cnki.issn1671-5381.2023.04.026

-

J. Bai, Y. Zhang, and S. Wu, “Review study of physical and mechanical characteristics on mixed soil with scrap tire rubber particles,” Jordan Journal of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 171–179, 2020.

-

J.-G. Bai, W.-Q. Kou, and H.-J. Li, “Numerical simulation of the deformation behavior of a composite foundation consisting of rubber particle loess-CFG under dynamic loading,” Journal of Vibroengineering, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 1237–1248, Aug. 2024, https://doi.org/10.21595/jve.2024.24110

-

Y. Song and L. Yang, “Mechanical properties of loess and filling materials of high-speed railway vibration isolation trench in loess area,” Science of Advanced Materials, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 760–771, Apr. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1166/sam.2022.4260

-

Z. Hu, Z. Liu, and Z. Zhang, “Test on influence of rubber powder on dynamic mechanic properties of manipulated loess,” (in Chinese), Journal of Chang’an University (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 462–67, 2013, https://doi.org/10.19721/j.cnki.1671-8879.2013.04.011

-

S. Chai, X. Li, Y. Li, J. Liu, D. Quan, and Z. Fan, “Experimental study on dynamic properties of loess improved by rubber particles and EICP technology,” (in Chinese), Advanced Engineering Science, Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 134–146, 2024, https://doi.org/10.15961/j.jsuese.202300961

-

Y. Chen, S. Chai, D. Cai, W. Wang, X. Li, and J. Liu, “Experimental study on shear mechanical properties of improved loess based on rubber particle incorporation and EICP technology,” Frontiers in Earth Science, Vol. 11, pp. 1–13, Sep. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1270102

-

Z. Liu, X. Du, D. Liu, J. Jia, C. Liu, and J. Bai, “Experimental study on unconfined compressive strength of loess mixed with rubber particles,” (in Chinese), Construction Engineering Technology and Design, No. 2, p. 443, 2020.

-

W.-Q. Kou, J.-G. Bai, H.-J. Li, and Q.-H. Liu, “Study on compaction characteristics and discrete element simulation for rubber particle-loess mixed soil,” Insight – Civil Engineering, Vol. 7, No. 1, p. 618, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.18282/ice.v7i1.618

-

S. Chai et al., “Experimental study on the influence of adding rubber powder on strength characteristics of remoulded loess,” in 8th International Conference on Hydraulic and Civil Engineering: Deep Space Intelligent Development and Utilization Forum (ICHCE), Vol. 19, pp. 154–158, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/ichce57331.2022.10042670

-

Y. Sun and F. Zhao, “Improvement of collapsible loess by rubber particulate lime-soil,” Journal of Hebei Institute of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 83–87, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1008-4185.2003.02.015

-

Z. Li and H. Zhang, “Compression properties of granulated rubber-loess mixtures as a fill materials,” Frontiers of Green Building, Materials and Civil Engineering, Vol. 71-78, pp. 673–676, 2011, https://doi.org/10.4028 /www.scientific.net/amm.71-78.673

-

F. Wang, “Experimental study on improvement of collapsible loess foundation with fly ash + lime + waste tire rubber particles,” (in Chinese), Aging and Application of Synthetic Materials, Vol. 51, No. 4, pp. 86–89, 2022, https://doi.org/10.16584/j.cnki.issn1671-5381.2022.04.046

-

“A method of reinforcing loess with rubber particles combined with EICP,” (in Chinese), CN118745728A, China National Intellectual Property Administration, China, Oct. 2024.

-

Z. Wang, X. Gan, and D. Wu, “Experimental study on shear strength and dynamic deformation characteristics of saturated rubber-sand,” (in Chinese), Engineering Technology Research, Vol. 9, pp. 109–111, 2024, https://doi.org/10.19537/j.cnki2096-2789.2024.08.035

-

A. Assadollahi, B. Harris, and J. Crocker, “Effects of shredded rubber tires as a fill material on the engineering properties of local Memphis loess,” Geo-Chicago 2016, Vol. 271, pp. 738–745, Aug. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784480144.073

-

W. Yao, “Experimental analysis of compression characteristics of collapsible loess,” (in Chinese), Traffic World, Vol. 15, pp. 98–100, 2024, https://doi.org/10.16248/j.cnki.11-3723/u.2024.15.035

-

S. Zhao, R. Zhu, and Q. Zhao, “Analysis of the effect of void ratio and water content on loess collapsibility,” (in Chinese), Yunnan Water Power, Vol. 12, pp. 333–337, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-3951.2023.12.072

-

X. Li, Y. Wang, L. Ma, X. Peng, and Y. Wang, “Study on the collapsibility of loess in revolutionary sites in Yanan area,” (in Chinese), Gansu Science and Technology, Vol. 40, No. 8, pp. 43–48, 2024.

-

H. Huang, R. Liu, X. Liu, and M. Liu, “Research progress on collapsible characteristics of loess and its modification methods,” (in Chinese), Journal of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 1–16, 2024, https://doi.org/10.19815/j.jace.2023.08056

-

Y. Li, G. Yang, and W. Ye, “Deterioration law and microscopic mechanism of hydraulic characteristics of undisturbed loess in Ili under freeze-thaw action,” (in Chinese), Journal of Engineering Geology, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 1261–1268, 2023, https://doi.org/10.13544/j.cnki.jeg.2022-0730

About this article

The authors would like to thank Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Natural Science Foundation (2023LHMS05048) for this study.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Hai-jun Li is mainly responsible for investigation, data curation, visualization and writing-original draft preparation. Jian-guang Bai is mainly responsible for conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition and project administration. Wen-qi Kou is mainly responsible for methodology, validation, writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.