Abstract

The integration of 3D printing technology with geopolymer materials offers a sustainable alternative to conventional construction methods, significantly reducing CO2 emissions. However, challenges such as rapid setting, limited workability, and weak interlayer bonding limit their broader application. This review summarizes recent progress in 3D printed geopolymer composites, focusing on materials selection, rheological optimization, buildability, and mechanical performance enhancement. Strategies including the use of rheology modifiers, fiber reinforcements, nano-additives, and process optimization have shown promise in improving printability and structural performance. Remaining challenges, such as balancing setting time and printability and enhancing interlayer adhesion, are also discussed. Future research directions are proposed to further advance the development of high-performance, low-carbon geopolymer 3D printing materials for sustainable construction.

1. Introduction

3D printing is reshaping construction by automating the fabrication of complex forms with less labor, shorter schedules, and lower waste. Geopolymers, produced by alkali activation of aluminosilicate precursors (fly ash, slag, metakaolin), offer low carbon emissions, high early strength, and strong thermal/chemical resistance, making them a credible alternative to Portland cement. Their adoption in printing is constrained by rapid setting and narrow workability windows (typically 20 to 30 min), which demand tight control of rheology and formulation to secure smooth extrusion and buildability [1]. Reported remedies include inorganic retarders (e.g., barium chloride), activator optimization, and the use of superplasticizers and viscosity modifiers [2]. Aggregate content and particle packing govern fluidity and print stability, while design ranges for yield stress and viscosity guide mix tuning. Fiber reinforcement (steel, PVA) mitigates anisotropy and improves interlayer and overall mechanical performance. This review screens literature from 2015 to 2025 across major databases; over 100 records were identified and about 60 selected for depth and experimental relevance. Despite progress, key challenges persist: balancing setting and workability, weak interlayer adhesion, and shrinkage/cracking. Current efforts focus on multifunctional admixtures, fiber engineering, and real-time monitoring to advance sustainable, high-performance geopolymer printing.

2. Materials and 3D printing technology

2.1. Binder systems and mix design

The selection of materials for 3D printed geopolymer composites plays a decisive role in ensuring the printability, mechanical properties, and long-term durability of the structures [3]. Typically, these composites are produced by alkali-activating aluminosilicate precursors, supplemented with various aggregates, admixtures, and fibers to tailor the fresh and hardened behavior.

2.1.1. Precursor materials and activators

Geopolymer binders, produced by alkali-activating aluminosilicate precursors (fly ash, slag, metakaolin), are attractive for 3D printing due to lower environmental impact and high early strength. Rapid setting and limited thixotropy hinder continuous extrusion and interlayer bonding, but tuning activator concentration and adding retarders such as sodium gluconate can extend open time without sacrificing long-term strength; Gao et al. [4] reported delayed hydration/hardening, reduced yield stress, increased shear-thickening, a drop in 3-day strength, and largely unchanged or slightly improved 28-day strength. Shilar [5] surveyed binder systems and their influence on hardened properties, offering comparative guidance for selecting formulations (Table 1; Fig. 1).

Table 1Impact of various binders on the hardened properties of geopolymer [5]

Binders used | Molarity (M) | Particle size (μm) | Major chemical composition | Compressive strength (MPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Flexural strength (MPa) | Bulk density (kg/m3) |

Metakaolin | 8 | 10-50 | SiO2, Al2O3 | 40 | 4 | 8 | 1200 |

Fly Ash | 10 | 5-20 | SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3 | 35 | 3.5 | 7 | 1100 |

GGBS | 12 | 5-25 | SiO2, Al2O3, CaO | 45 | 4.5 | 9 | 1250 |

Rice Husk Ash | 6 | 5-40 | SiO2 | 30 | 3 | 6 | 1000 |

Silica Fume | 8 | 1-5 | SiO2 | 50 | 5 | 10 | 1300 |

Red Mud | 10 | 10-50 | Al2O3, Fe2O3, SiO2, CaO | 35 | 3.5 | 7 | 1200 |

Clay | 8 | 5-20 | Al2O3, SiO2, MgO, Fe2O3 | 30 | 3 | 6 | 1100 |

Fig. 1The impact of different binders on the compressive, tensile, and flexural strength properties [5]

![The impact of different binders on the compressive, tensile, and flexural strength properties [5]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img1.jpg)

2.1.2. Enhancing printability and rheological control

Printability, as defined by Nerella et al. [6], is the capacity to pump, extrude, and retain geometry after deposition. It is governed by rheology – especially yield stress, plastic viscosity, and structural build-up rate – which can be tuned via solid-to-liquid ratio, particle packing, and viscosity modifiers; for example, ~0.1 % hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) increased yield stress and shape retention while reducing slump flow. Short fibers (PVA, cellulose) act as micro-reinforcements that raise green strength and limit deformation during multilayer stacking. Robust printability requires coordinated control of reaction kinetics (Fig. 2) [7], mix design, environment, and advanced monitoring/prediction to achieve defect-free, high-performance geopolymer prints.

Fig. 2Reaction mechanism of the metakaolin-based geopolymer system [7]

![Reaction mechanism of the metakaolin-based geopolymer system [7]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img2.jpg)

2.1.3. Buildability and structural performance

Buildability is the ability to retain geometry and support subsequent layers; stability requires gravity-induced shear to stay below the early-age yield stress. DIC-guided tuning improves it via (i) reactive nano-additives (nano-SiO₂, NGPs) to boost thixotropy/static yield stress, (ii) mix design with HPMC+PCE and nanocellulose+MgO, and (iii) parameter control (larger nozzles, adequate rest time). Because buildability can conflict with interlayer bonding, co-optimize with multi-scale fibers to raise green strength and interfacial shear, while balancing rapid network formation with workable open time.

2.2. 3D Printing technology for geopolymers

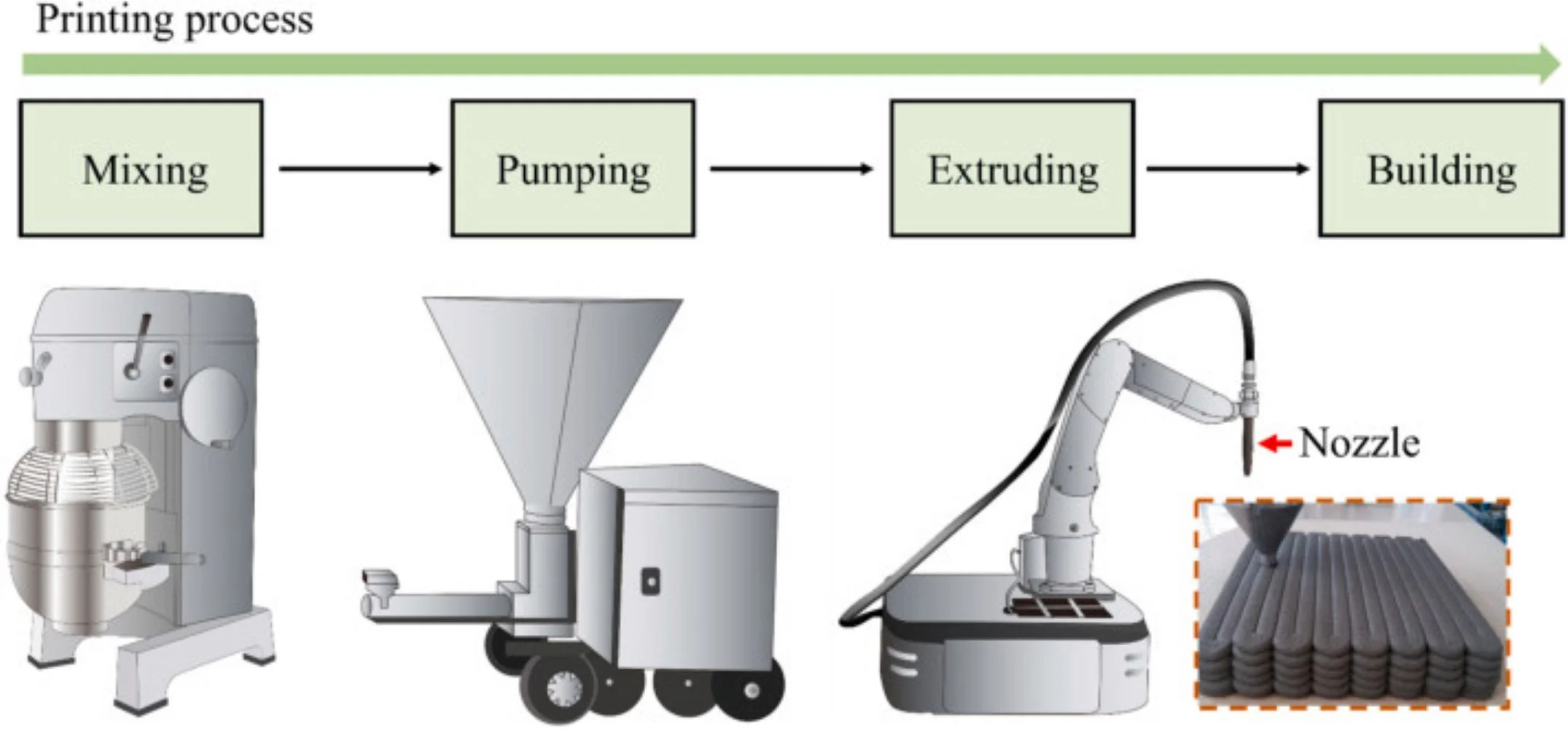

Fig. 3 illustrates the primary steps involved in the extrusion-based 3D printing of geopolymer, which include mixing, pumping, extrusion, and layer-by-layer construction [8]. Typically, the prepared mixture is conveyed to the extruder through the pumping mechanism, where it is deposited sequentially to form the intended geometry.

Fig. 3Typical printing process for extrusion-based 3D printed geopolymers [8]

![Typical printing process for extrusion-based 3D printed geopolymers [8]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img3.jpg)

Beyond extrusion, key technologies for geopolymer AM include: SLS, which laser sinters powders into strong parts across many materials but is costly and complex for construction; FDM, which melts and extrudes filaments at low cost with recyclability but lower resolution and surface finish; SLA, which photopolymerizes resins with high precision and quality, suited to detailed parts rather than large structures; and binder jetting, which selectively deposits a binder on a powder bed and is evolving for niche uses. Building on these, construction employs gantry, robotic-arm, and crane-type printers; Table 2 summarizes machine types, structures, pros/cons, and typical applications [9].

Table 2Comparison of main 3D printing technologies for geopolymers

Printer type | Structural features | Advantages | Disadvantages | Application scope |

Gantry-style 3D Printer | Cartesian XYZ gantry, stable frame | Stable structure, easy operation, widely used in factory prefabrication | Bulky and heavy (10-20 tons), limited span, slow printing speed, high energy consumption | Prefabricated components, large-scale industrial production |

Tower Crane-style Printer | Mobile and flexible, automatic lifting | Lightweight, low cost, fast assembly, suitable for high-rise and large structures | Requires precise control, complex system integration | Large-scale infrastructure, multi-story buildings |

D-Shape Printer | Powder bed with binder jetting | Can print complex shapes, low material cost | Low mechanical strength, unsuitable for load-bearing parts | Artistic decorations, small components |

FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling) | Melts and extrudes material filament | Simple equipment, suitable for small parts | Rough surface finish, nozzle clogging, slow speed | Small parts, prototypes |

Delta (Parallel-arm) Printer | Parallel-arm 3D motion system | Compact footprint, lightweight | Limited workspace, lower accuracy on complex curves | Desktop printing, small-scale models |

Inkjet Printing | Deposits droplets of binder or slurry | High detail, multi-material capability, low cost | Limited scale, low mechanical strength | Decorative elements, functional coatings |

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | Laser fuses powder layer by layer | High resolution, strong parts, no supports needed | High cost, complex system, limited for large-scale construction | Precision components, aerospace, biomedical |

3. Applications

3.1. Applications of 3D-printed geopolymer composites

Additive manufacturing enables complex, multifunctional geopolymer structures beyond casting. A representative advance is geopolymer/graphene oxide (GO) nanocomposites: Zhong et al. [10] demonstrated extrusion printing where GO tunes rheology for stable, continuous deposition. As Fig. 4 shows, GO nanosheets form a reinforcing network that enhances printability and, after sintering, imparts electrical conductivity for conductive/sensing components.

Scaling up this technology, Bong et al. [11] successfully fabricated a large, multi-layered staircase with complex geometry, demonstrating that optimized geopolymer mixtures can be employed for structural and architectural components in real-world construction. This example, shown in Fig. 5, highlights the potential of extrusion-based 3D printing to produce sizable, load-bearing elements with controlled layering and precision.

Fig. 4Illustration of the 3D-printing process and some 3D-printed structures. The colors of the printed samples turned from brownish to blackish when the GO loading increased [10]

![Illustration of the 3D-printing process and some 3D-printed structures. The colors of the printed samples turned from brownish to blackish when the GO loading increased [10]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img4.jpg)

Fig. 53D-printing of a staircase using the optimum 3D-printable geopolymer mixture (M5): a) 3D model of the staircase; b) during 3D-printing process; c) 3D printed staircase [11]

![3D-printing of a staircase using the optimum 3D-printable geopolymer mixture (M5): a) 3D model of the staircase; b) during 3D-printing process; c) 3D printed staircase [11]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img5.jpg)

a)

![3D-printing of a staircase using the optimum 3D-printable geopolymer mixture (M5): a) 3D model of the staircase; b) during 3D-printing process; c) 3D printed staircase [11]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img6.jpg)

b)

![3D-printing of a staircase using the optimum 3D-printable geopolymer mixture (M5): a) 3D model of the staircase; b) during 3D-printing process; c) 3D printed staircase [11]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img7.jpg)

c)

Material composition also plays a crucial role in printability and final properties. Xia et al. [12] studied geopolymer powders with different slag-to-fly ash ratios, revealing that mixtures with high fly ash content lacked sufficient reactivity at ambient temperatures, resulting in unsuccessful prints. The experimental results presented in Fig. 6 underscore the importance of tailoring raw materials to balance workability and mechanical strength for effective 3D printing.

Beyond these cases, the integration of nanoparticles and tailored geopolymer chemistries promises multifunctional composites with enhanced mechanical durability, thermal stability, and potential catalytic or adsorption functionalities. The combination of AM’s geometric freedom and geopolymer’s intrinsic material properties thus paves the way for innovative applications spanning construction, environmental remediation, energy storage, and smart sensing devices.

Fig. 6Powder-based 3D printed green cubes using geopolymer powders with different slag/fly ash ratios [12]

![Powder-based 3D printed green cubes using geopolymer powders with different slag/fly ash ratios [12]](https://static-01.extrica.com/articles/25087/25087-img8.jpg)

3.2. Challenges in 3D printing geopolymer materials

Despite progress, several obstacles limit adoption of 3D-printed geopolymers. Materials: high viscosity and long setting times complicate extrusion and demand tight control of temperature and flow; nanoparticles can destabilize rheology and reduce printability. Structure: layerwise fabrication causes anisotropy and weak interlayer interfaces, hindering overhangs; powder routes relax geometry limits but suffer low green strength, slower rates, and higher cost. Rough surfaces, dimensional drift, and post-processing needs persist, while elevated-temperature curing heightens shrinkage/cracking risk. Practicality: raw-material costs and safe handling of alkaline activators raise economic and safety burdens. Fully realizing the technology will require formulation optimization, better printing/curing strategies, and safer, energy-efficient, cost-effective processing.

4. Conclusions

Recent work has improved geopolymer printability and mechanics by using rheology-modifying admixtures, fiber reinforcement, and tuned process parameters (nozzle size, speed), boosting buildability, extrudability, and early-age strength for automated construction. Persistent hurdles include rapid setting that shortens open time, weak interlayer bonding and anisotropy that erode structural integrity, and the hard tradeoff between print-friendly rheology and long-term performance. Priorities ahead are low-carbon formulations, fiber/nano-reinforcement, and smart printing control to raise integrity and sustainability.

References

-

B. Panda, G. B. Singh, C. Unluer, and M. J. Tan, “Synthesis and characterization of one-part geopolymers for extrusion based 3D concrete printing,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 220, pp. 610–619, May 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.02.185

-

H. Zhang, F. Hu, Y. Duan, J. Liao, and J. Yang, “Mechanical properties and microstructure of highly flowable geopolymer composites with low-content polyvinyl alcohol fiber,” Buildings, Vol. 14, No. 2, p. 449, Feb. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020449

-

W. Chen et al., “Improving mechanical properties of 3D printable ‘one-part’ geopolymer concrete with steel fiber reinforcement,” Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 75, p. 107077, Sep. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107077

-

Y. Gao, T. Guo, Z. Li, Z. Zhou, and J. Zhang, “Mechanism of retarder on hydration process and mechanical properties of red mud-based geopolymer cementitious materials,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 356, p. 129306, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129306

-

F. A. Shilar, S. V. Ganachari, V. B. Patil, B. E. Bhojaraja, T. M. Yunus Khan, and N. Almakayeel, “A review of 3D printing of geopolymer composites for structural and functional applications,” Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 400, p. 132869, Oct. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132869

-

V. N. Nerella and V. Mechtcherine, “Studying the printability of fresh concrete for formwork-free concrete onsite 3D printing technology (CONPrint3D),” in 3D Concrete Printing Technology, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 333–347, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-815481-6.00016-6

-

L. Ricciotti, A. Apicella, V. Perrotta, and R. Aversa, “Geopolymer materials for bone tissue applications: recent advances and future perspectives,” Polymers, Vol. 15, No. 5, p. 1087, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15051087

-

V. C. Li et al., “On the emergence of 3D printable engineered, strain hardening cementitious composites (ECC/SHCC),” Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 132, p. 106038, Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106038

-

J. Archez, N. Texier-Mandoki, X. Bourbon, J. F. Caron, and S. Rossignol, “Shaping of geopolymer composites by 3D printing,” Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 34, p. 101894, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101894

-

J. Zhong, G.-X. Zhou, P.-G. He, Z.-H. Yang, and D.-C. Jia, “3D printing strong and conductive geo-polymer nanocomposite structures modified by graphene oxide,” Carbon, Vol. 117, pp. 421–426, Jun. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2017.02.102

-

S. H. Bong, M. Xia, B. Nematollahi, and C. Shi, “Ambient temperature cured ‘just-add-water’ geopolymer for 3D concrete printing applications,” Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 121, p. 104060, Aug. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104060

-

M. Xia, B. Nematollahi, and J. Sanjayan, “Printability, accuracy and strength of geopolymer made using powder-based 3D printing for construction applications,” Automation in Construction, Vol. 101, pp. 179–189, May 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.01.013

About this article

The research was supported by the Key R&D Project in Shaanxi Province (No. 2023-YBGY-495).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.