Abstract

To address the difficulties in extracting fault features of rolling bearings and the low diagnostic accuracy, a fault diagnosis method for rolling bearings is proposed. This method integrates the Golden Sine Algorithm (GSA) with the Subtraction-Average-Based Optimizer (SABO) to form a Golden Sine Improved SABO Optimization Algorithm (GSABO). The GSABO algorithm is used for parameter optimization of Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) and Kernel Extreme Learning Machine (KELM) in the fault diagnosis process. Firstly, the chaotic mapping strategy is used to optimize the population initialization of the Subtractive Clustering-Based Adaptive Optimization (SCAO) algorithm, enhancing population diversity. Secondly, the Golden Sine Algorithm (GSA) is integrated to improve the displacement algorithm, enhancing global search capability and effectively avoiding getting trapped in local optima. Then, the GSABO-VMD (Golden Sine Algorithm-Based Optimized Variational Mode Decomposition) is employed to decompose the rolling bearing fault signals, and the envelope entropy minimum criterion is used to select the effective modal components. Finally, time-frequency domain indicators of the selected modal components are computed to form a feature matrix, which is then input into GSABO-KELM (Golden Sine Algorithm-Based Optimized Kernel Extreme Learning Machine) for fault classification and recognition. Experimental analysis shows that compared to the unmodified SABO algorithm, GSABO has significant advantages in terms of escaping local optima, convergence speed, and accuracy. When compared with other traditional algorithms, GSABO-VMD-KELM achieves recognition accuracies of 99.3333 % and 99.0476 % on bearing data from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) and Xi'an Jiao tong University (XJTU), respectively. This demonstrates the accuracy and superiority of the algorithm and provides valuable insights for engineering applications in rolling bearing fault diagnosis.

Highlights

- The SABO algorithm is improved by incorporating chaotic mapping strategies and the golden sine algorithm. Compared with other optimization algorithms, the proposed GSABO algorithm demonstrates superior performance in optimization accuracy, computational efficiency, and convergence capability

- By integrating the GSABO algorithm with VMD and KELM, this study provides enhanced accuracy and convergence for rolling bearing mechanical fault diagnosis, offering new possibilities for existing fault diagnosis technologies

- The GSABO algorithm is employed to achieve adaptive selection of VMD parameters, thereby reducing the complexity of the problem

1. Introduction

The health condition of rolling bearings is directly related to the safe and stable operation of equipment. Timely detection of faults in key rolling bearings is crucial for ensuring the reliability and safety of machinery [1-3]. Once a rolling bearing in mechanical equipment fails, it may lead to equipment downtime, production interruptions, or even safety accidents, which can have a severe impact on production and operations [4-6]. Therefore, it is especially important to diagnose and predict bearing faults in a timely manner. However, due to the complex working environment of mechanical equipment, bearings are susceptible to issues such as wear and fatigue [7], which increases the difficulty of fault diagnosis. Therefore, researching high-precision bearing fault diagnosis methods is of great significance for enhancing the safety and reliability of mechanical equipment.

The fault signals of rolling bearings exhibit non-stationary and nonlinear characteristics [8]. Therefore, signal decomposition algorithms are regarded as useful tools for extracting fault features [9]. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) [10] decomposes signals based on the time-scale characteristics of the data itself, without the need to preset any basis functions. Once proposed, this methodology has been extensively and successfully implemented in the domain of fault diagnosis. Nevertheless, the ultimate efficacy and the mode admixture have significantly constrained its applicability. To effectively resolve these challenges, a sequence of recursive decomposition methodologies has been systematically developed, such as Local Mean Decomposition (LMD) [11], and Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) [12], Improved Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (ICEEMDAN) [13]. Nevertheless, the recursive decomposition approach fails to fundamentally resolve the issue of mode mixing [14]. In addressing this particular concern, Konstantin et al. [15] proposed the Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) technique. Due to its superior filtering capabilities and rigorous theoretical foundation, VMD has gained widespread popularity and recognition among researchers since its introduction [16]. Meng [17] proposed an enhanced VMD method that precisely extracts fault features through adaptive adjustment of the penalty factor. Yang et al. [18] employed the simulated annealing (SA) algorithm to optimize VMD parameters, successfully achieving early fault detection. Wang et al. [19] introduced a particle swarm optimization-based VMD method for complex rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Although these optimization algorithms demonstrate satisfactory performance in parameter optimization, these algorithms frequently converge to local optima, potentially leading to overfitting or underfitting scenarios that may degrade overall performance.

Following the completion of feature extraction from rolling bearing fault signals, the extracted feature matrix requires identification and diagnosis. With the rapid development of science and technology, deep learning diagnostic models are increasingly applied in the fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Such as dynamic collaborative adversarial domain adaptation networks (DCADAN) [20], task-oriented Theil index-based meta-learning networks (TTIMN-GCS) [21], attention-guided hierarchical wavelet convolutional networks (AHWCN) [22]. Although these methods have all demonstrated excellent performance in the application of fault diagnosis for rolling bearings, they still face problems such as complex computation, long diagnosis time, lack of hyperparameter optimization strategies, and reliance on prior knowledge of fault features for parameter setting. Common fault recognition models include Backpropagation Neural Networks (BPNN) [23] and Extreme Learning Machines (ELM) [24], among others. The BP neural network fault identification model suffers from several limitations, including high learning costs and susceptibility to overfitting when handling noisy data [25]. Meanwhile, ELM faces challenges such as random initialization of input weights and potential overfitting issues [26]. In response to the issues, Huang et al. [27] proposed the KELM algorithm, which combines the kernel method with the framework of extreme learning machines. It can effectively handle nonlinear relationships and high-dimensional data, offering fast training speeds and strong generalization capabilities. However, the KELM algorithm also has some limitations, as its performance is significantly influenced by the regularization coefficient and the kernel function parameter. If and are not selected properly, they may negatively impact the model’s classification accuracy. Zhao et al. [28] employed the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to optimize the regularization coefficient and kernel function parameter of the KELM algorithm, thereby enhancing its effectiveness in gearbox fault diagnosis. Yang et al. [29] proposed a rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on variational mode decomposition optimized by an improved artificial fish swarm algorithm and multi-feature vector fusion with extreme learning machines. However, both particle swarm optimization and artificial fish swarm algorithms are prone to premature convergence and getting trapped in local optima, exhibiting poor robustness. The subtraction-average-based optimization algorithm is a novel optimization algorithm [30] with outstanding optimization performance. Lu Fan [31] verified that using the subtraction-average-based optimizer (SABO) to optimize the selection process of the mode number and penalty factor in variational mode decomposition (VMD) improved the classification accuracy of rolling bearing fault diagnosis. However, the SABO algorithm also has the issue of easily falling into local optima. In their study on rolling bearing fault diagnosis based on adaptive local iterative filtering (ALIF) and time-shifted multi-scale fluctuation dispersion entropy (TMFDE), Zhao Jiahao et al. [32] noted that the MFDE method achieved a maximum classification accuracy of 82 % and a minimum classification accuracy of 74 %, with a difference of 8 %. This indicates that falling into local optima significantly impacts the classification accuracy of rolling bearing fault diagnosis.

In summary, to further improve the classification accuracy of rolling bearing fault diagnosis, this paper proposes an improved subtraction-average-based optimizer algorithm, GSABO. The method combines GSABO with VMD and KELM, where the GSABO-KELM model classifies the feature matrix formed by calculating the envelope entropy of the IMF components screened after GSABO-VMD decomposition. Ultimately, this approach identifies the fault types of rolling bearings. The superiority of the proposed method is validated using datasets from Case Western Reserve University and Xi’an Jiaotong University.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) The SABO algorithm is improved by incorporating chaotic mapping strategies and the golden sine algorithm. Compared with other optimization algorithms, the proposed GSABO algorithm demonstrates superior performance in optimization accuracy, computational efficiency, and convergence capability.

(2) The GSABO algorithm is employed to achieve adaptive selection of VMD parameters, thereby reducing the complexity of the problem.

(3) By integrating the GSABO algorithm with VMD and KELM, this study provides enhanced accuracy and convergence for rolling bearing mechanical fault diagnosis, offering new possibilities for existing fault diagnosis technologies.

2. Fundamental theory

2.1. VMD

The key step of the VMD algorithm lies in constructing and solving the constrained variational model. The constrained variational model is defined as follows:

where, represents the set of IMF components obtained from the decomposed original signal; denotes the set of center frequencies corresponding to the IMF components; is the time derivative operator; is the original input signal; indicates the number of decomposition layers.

To obtain the optimal solution for Eq. (1), it is essential to introduce penalty factor and Lagrange multiplier , thereby transforming Eq. (1) into an unconstrained variational model as follows:

By employing the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM), the original minimization problem is transformed into a saddle-point problem involving the augmented Lagrangian function, thereby facilitating the determination of the optimal solution for Eq. (1). The update procedures for and are as follows:

2.2. SABO

This algorithm exhibits strong optimization capability and rapid convergence speed. The algorithmic procedure is as follows:

1) Algorithm initialization.

The initial positions of search agents in the search space are randomly initialized using the following equation:

where, represents its -th dimensional decision variable in the search space; represents the number of search agents; denotes the dimensionality of decision variables; is a random number within the interval [0, 1]; and represent the upper bound and lower bound, respectively, of the -th dimensional decision variable.

2) Mathematical model of SABO.

The concept of computing the arithmetic mean in SABO is entirely unique, as it is based on a special operator "" defined as the subtraction of search agent from search agent , as shown in Eq. (6):

where, is an -dimensional vector; and represent the objective function values of search agent and search agent .

In the SABO algorithm, the displacement of any search agent in the search space is computed as the arithmetic mean of the subtraction from each search agent . The position update scheme is as follows:

where is the total number of search agents, and is an -dimensional vector, each component is a random number sampled from a normal distribution over the interval [0, 1].

The particle position update formula is as follows:

where and are the objective function values of search agent and .

2.3. Golden sine-enhanced SABO optimization algorithm

Although the SABO optimization algorithm exhibits stronger optimization capabilities than traditional optimization algorithms, it still suffers from issues such as premature convergence and getting trapped in local optima. To avoid these problems, chaotic mapping and the golden sine method are integrated to enhance the global search ability and optimization accuracy of the SABO algorithm. The main improvement steps consist of the following three steps:

1) Chaotic mapping can enhance the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the algorithm, prevent the algorithm from converging to local optimal solutions, and it can increase the randomness and diversity of the algorithm, improving the global search accuracy and convergence speed. Among them, the Tent map [33] is simple and has better traversal uniformity and search speed. Therefore, the Tent map is used to optimize the initial positions of particles, with the formula as follows:

where, represents the number of mapping iterations; denotes the value of the particle position after the -th mapping; ; controls parameter :

The Lyapunov exponent measures the sensitivity of the system to initial conditions (the intensity of chaos), and its calculation formula is as follows:

The derivative of the Tent map is obtained as follows:

The absolute value of the derivative is always:.

Substituting the into the Lyapunov exponent formula yields:

So, when , the system exhibits maximum chaotic behavior, so is selected.

2)The Piecewise chaotic map is employed to generate random values for replacing in the original SABO algorithm. In Eq. (7) of the SABO algorithm, is a random value within the interval [0, 1]. By substituting with random values generated using the Piecewise chaotic map, the algorithm benefits from a more uniform distribution of randomness, thereby enhancing particle diversity during the computation of average differences. The formula for the Piecewise chaotic map is as follows:

where the range of and is [0, 1].

3) Integrate the Golden Sine Algorithm to assist particles in escaping local optima. The SABO algorithm does not utilize the global best value in each iteration but instead updates particle positions by computing the subtraction average of all particles’ positions. Consequently, if the initial particle positions are poorly distributed, the algorithm is highly prone to falling into local optima. To address this issue, the proposed improvement strategy is as follows: if the fitness value of a particle remains unchanged in the current iteration, the Golden Sine Algorithm (GSA) is employed to update the particle’s position [34]. This approach neither significantly increases the computational burden of fitness evaluations nor leverages the global optimization strength of the Golden Sine Algorithm to help SABO escape local optima. The position update formula of the Golden Sine Algorithm is shown in Eq. (15):

where, represents the spatial position of the -th individual in the -dimensional search space during the -th iteration; is the global best position at the -th iteration; is a random number within the range [0, 2]; is a random number within the range [0, ]; and are coefficients derived from the golden ratio. These coefficients effectively narrow the search space while guiding the current values toward the optimum, ensuring the algorithm’s convergence; Golden ratio coefficient , , . The initial values of and are set to and , respectively. Subsequently, and adapt dynamically based on changes in the objective value, leading to corresponding updates in coefficients and .

2.4. KELM

While retaining ELM's three-layer network structure (input layer, hidden layer, and output layer), KELM transforms complex, linearly inseparable datasets in low-dimensional space into inner product operations in high-dimensional space. This approach significantly improves the model’s stability and generalization capability.

For sets of fault samples , the number of hidden layer neurons in the ELM network is , and the activation function is , whose mathematical expression is:

where, denotes the connection weights between the input layer and hidden layer; represents the bias vector of the hidden layer neurons; is the hidden layer output matrix; is the output weight matrix between the hidden layer and output layer; is the target output matrix.

The formula for is:

where, is the identity matrix, and is the regularization coefficient.

Introduce the kernel function, expressed as:

where, is the kernel function.

The radial basis function (RBF), a commonly used kernel function, is selected as the kernel. The RBF kernel can be defined as:

where, is the nuclear parameter.

Therefore, can be rewritten as:

where represents the number of samples.

2.5. Fault diagnosis process

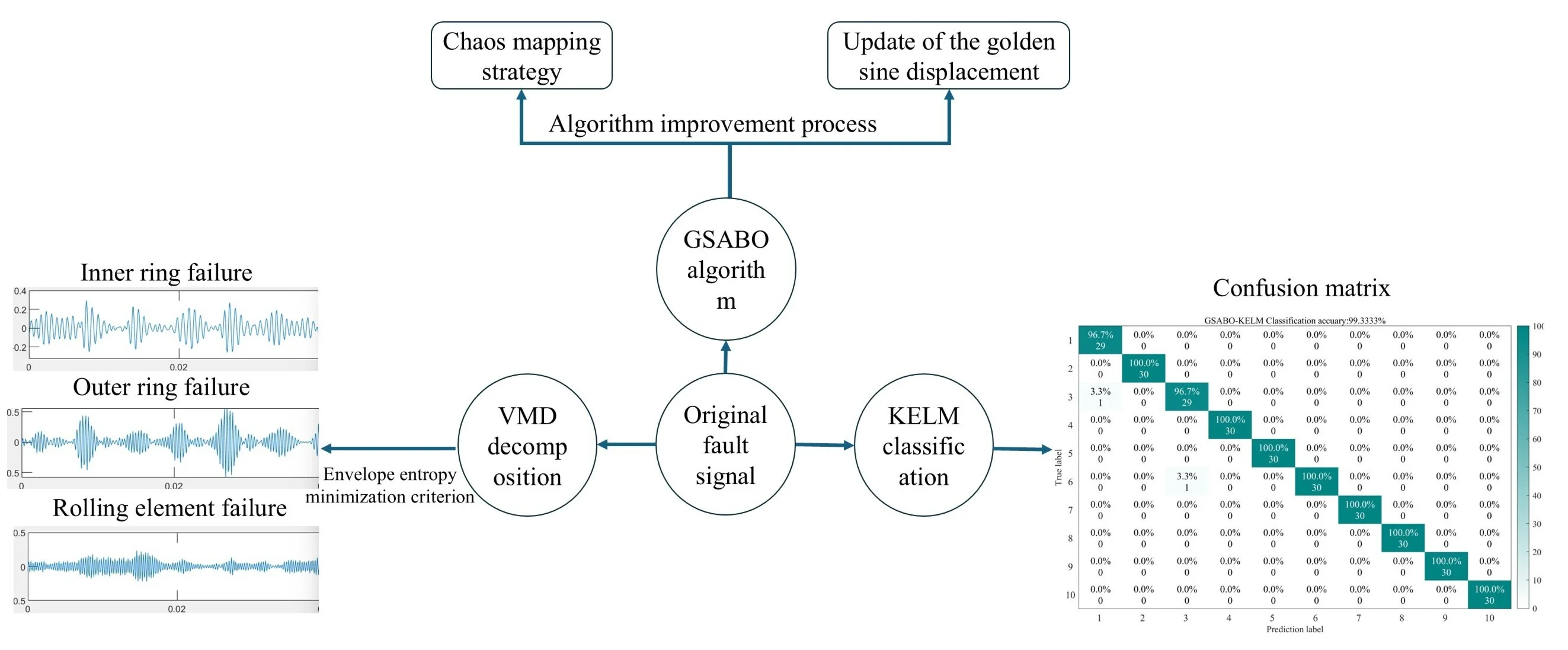

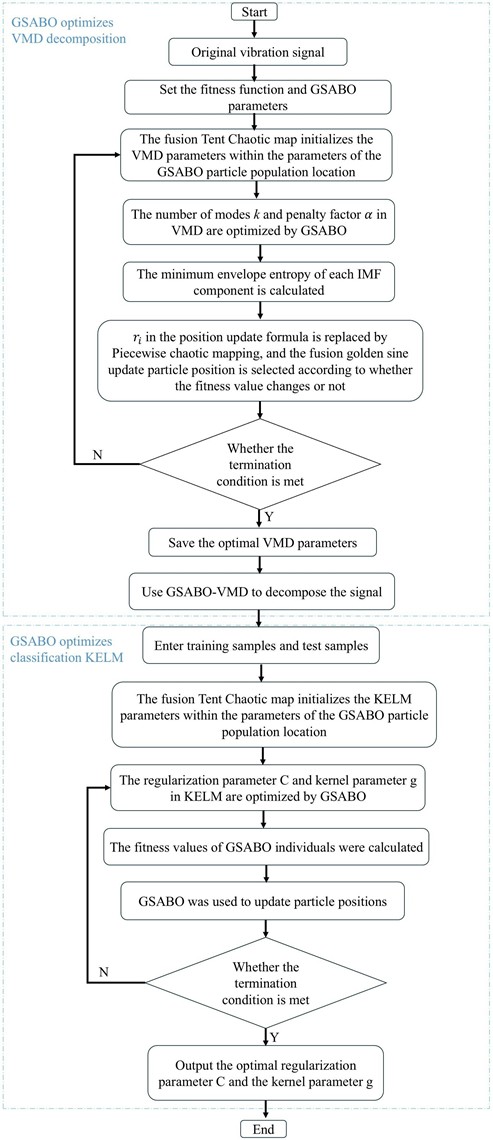

The overall flowchart for fault diagnosis is shown in Fig. 1. The specific steps for optimizing VMD and KELM using GSABO are as follows:

Step 1: Input the original vibration data and set the fitness function as well as the GSABO parameters.

Step 2: Initialize the population and positions of particles in the GSABO algorithm for VMD parameters using the Tent chaotic map.

Step 3: Decompose the signal using VMD and calculate the envelope entropy of each IMF component

Step 4: Replace in the position update formula with the Piecewise chaotic map and selectively fuse the golden sine strategy to update particle positions based on fitness value variations.

Step 5: Evaluate whether to update the current best solution. If the fitness value of the particle's current position is better than the historical best fitness value, update this position as the new position for the corresponding population particle and save this fitness value as the optimal fitness value

Step 6: Perform iterative cycles until the preset stopping criteria are met.

Step 7: Decompose the signal using the optimal parameters obtained from GSABO-optimized VMD.

Step 8: Divide the dataset into training samples and testing samples.

Step 9: Initialize the population and positions of GSABO particles within the KELM parameter range by incorporating the Tent chaotic mapping.

Step 10: Optimize the regularization coefficient and kernel parameter in KELM using GSABO, and calculate the fitness value of each GSABO individual

Step 11: Update particle positions using the GSABO algorithm.

Step 12: Determine whether the termination criteria are met. If satisfied, proceed to the next step; otherwise, return to Step 10.

Step 13: Obtain the optimal regularization parameter and kernel parameter.

Fig. 1Flowchart of the GSABO-VMD-KELM fault diagnosis method

3. Simulation experiment

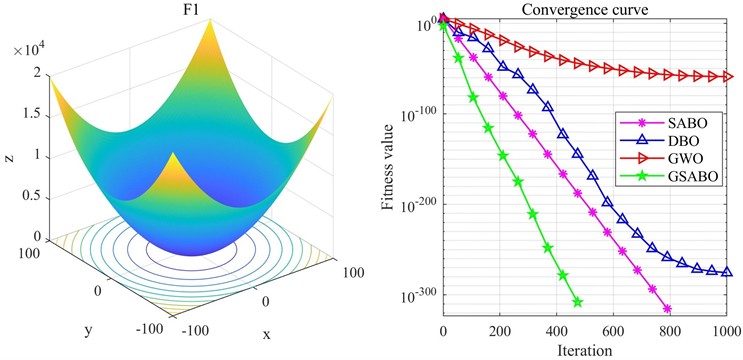

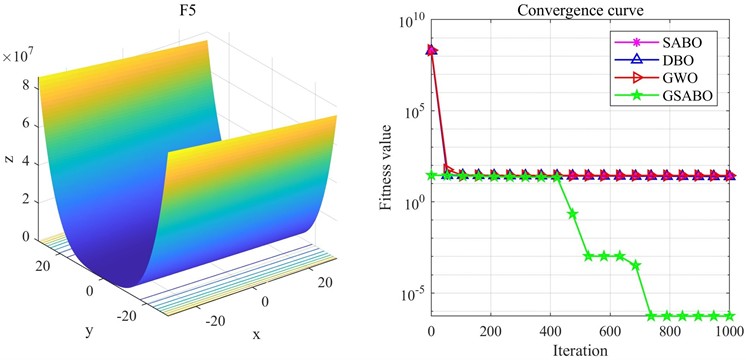

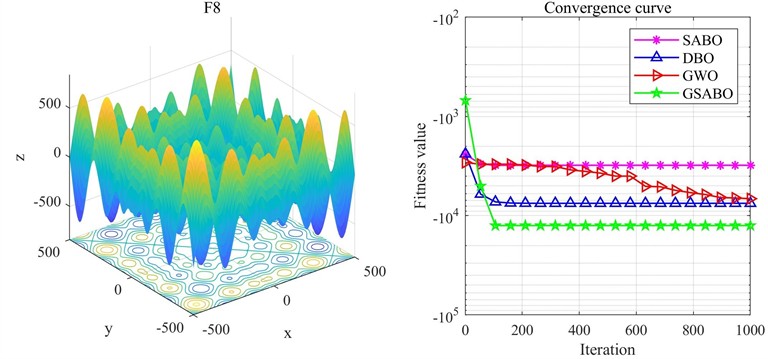

To demonstrate the advantages of the improved SABO optimization algorithm incorporating golden sine (GSABO) over SABO and other traditional optimization algorithms, the F1, F5, and F8 functions from the CEC2005 benchmark test set were selected for testing and comparison. The expressions of these functions are shown in Table 1, and the comparison results are illustrated in Fig. 2-4.

Table 1Basic function test information

Function | Dimensionality | Search range |

30 | [–100, 100] | |

30 | [–30, 30] | |

30 | [–500, 500] |

Fig. 2Comparison of optimization results on F1 function

Fig. 3Comparison of optimization results on F5 function

Fig. 4Comparison of optimization results on F8 function

From the comparative results, it can be observed that F5 and F8 are among the most challenging functions in the CEC2005 benchmark set for evaluating optimization algorithm performance. For F5, whose theoretical minimum is 0, the improved algorithm achieved an optimization value of 6.19×10-6, whereas the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO), and Subtraction-Average-Based Optimizer (SABO) all yielded values around 27. For F8, a multimodal function with multiple peaks, intelligent algorithms are highly prone to falling into local optima during optimization. Its theoretical minimum is –12569.5, and GSABO obtained a near-optimal value of –12569.4737, which is extremely close to the theoretical optimum. Combined with the results in Fig. 4, GSABO outperforms the other three algorithms and exhibits faster convergence speed. In summary, based on the test results of three functions, the improved GSABO demonstrates significant advantages in both convergence speed and final optimization accuracy compared to the other algorithms.

4. Experimental analysis

4.1. Case 1

4.1.1. Data collection

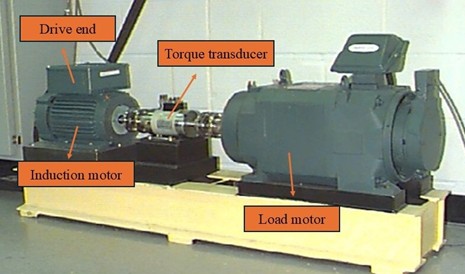

To validate the effectiveness of the GSABO algorithm in rolling bearing fault diagnosis, an empirical evaluation was conducted using the bearing dataset from CWRU. Fig. 5 shows the basic configuration of the test rig. The specifications of the bearing data are as follows: SKF bearings were used, the motor was running at a speed of 1797 r/min, and the load was set to zero horsepower, with a sampling frequency of 12 kHz. The dataset covers four different fault conditions: normal state, inner race fault, outer race fault, and ball fault, with corresponding fault diameters of 0.007 inches, 0.014 inches, and 0.021 inches, respectively.

There are 10 types of faults. For the convenience of the experiment, these faults are coded as follows: “1” represents the normal state, “2-4” represent inner ring faults with diameters of 0.007, 0.014, and 0.021 inches, “5-7” represent rolling element faults with diameters of 0.007, 0.014, and 0.021 inches, and “8-10” represent outer ring faults with diameters of 0.007, 0.014, and 0.021 inches. Each fault signal contains 2048 sampling points, and there are 120 fault samples collected for each type of fault, with 90 samples used for the training set and 30 samples used for the testing set.

Fig. 5Bearing data acquisition platform of Case Western Reserve University

4.1.2. Fault signal GSABO-VMD decomposition

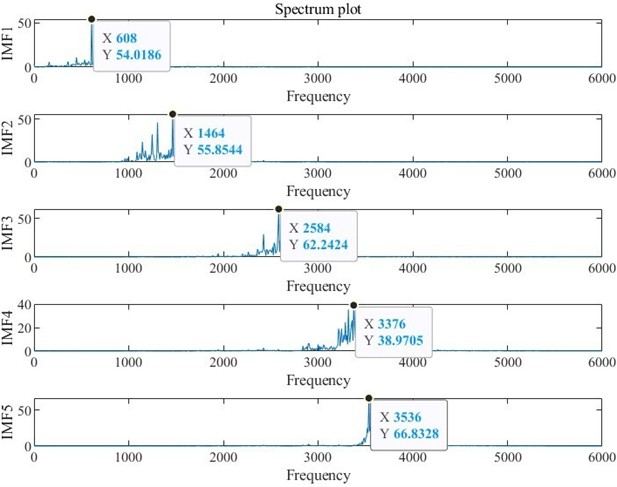

After acquiring the fault signal, the first step is to set the parameters for GSABO-VMD. The population size of GSABO is set to 15, and the maximum number of iterations is set to 20. The decomposition layer and the penalty factor are optimized within the ranges and , with the objective of minimizing the envelope entropy. Taking a fault signal with a fault size of 0.007 inches as an example, the optimization results obtained through GSABO are . The VMD decomposition results optimized by GSABO are shown in Fig. 6, while the decomposition results using the default parameter set [4, 2000] [35] are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6VMD frequency spectrum decomposition diagram after parameter optimization

According to the theoretical frequency calculation formula of the inner ring fault of rolling bearings, as shown in Eq. (22):

where, represents the diameter of the rolling element; represents the raceway pitch diameter; represents the contact angle of the bearing; represents the number of rolling elements; represents the frequency conversion.

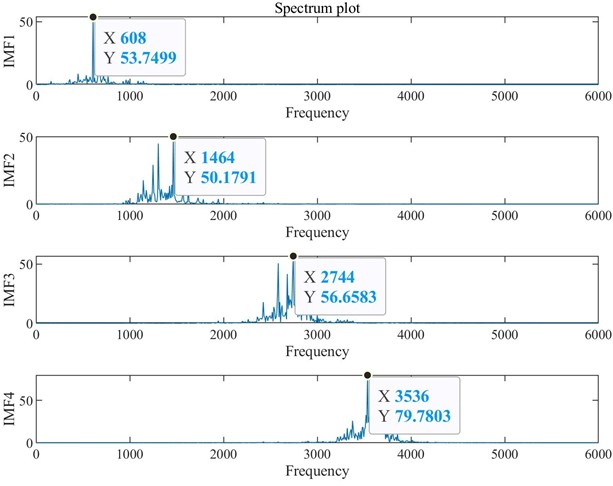

Fig. 7VMD frequency spectrum decomposition diagram with default parameters

The theoretical frequency of the inner ring fault of the 6205-2RS bearing can be calculated as 134.775 Hz, the fault frequency of the IMF4 component in Fig. 6 is 3376 Hz, which is very close to the 25 times fault frequency of the inner ring at 3369.375 Hz, while the fault frequency decomposed in Fig. 7 differs significantly from the fault frequency of the inner ring.

The optimized VMD decomposition includes inner ring failure frequency. As observed from the amplitude of the spectrogram, this component represents significant features of the original signal that were overlooked under default parameters. The results demonstrate that the optimized parameters can more effectively characterize the features of the original signal.

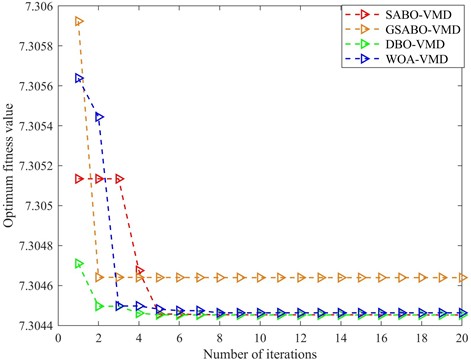

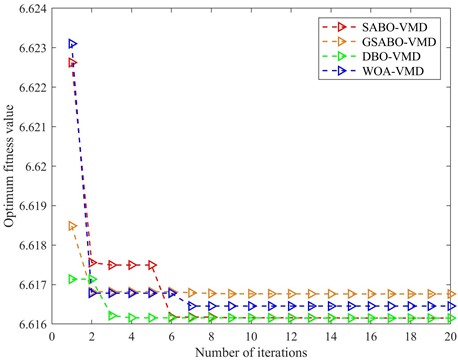

Fig. 8 shows the evolutionary curve comparison of the algorithms. GSABO achieves convergence at the 3rd generation, while the unimproved SABO converges at the 6th generation. DBO completes convergence at the 6th generation, and WOA reaches convergence at the 8th generation. Notably, GSABO demonstrates significantly better optimization performance than the other three algorithms, which clearly illustrates the superiority of the proposed optimization method.

4.1.3. Feature extraction from signal decomposition results

Prior to feature extraction from the IMF components obtained through GSABO-VMD decomposition, it should be noted that a smaller envelope entropy value indicates richer fault information, while a larger value suggests less fault information [36]. Given that each IMF component contains different characteristic quantities, we select the IMF component with the smallest envelope entropy for feature extraction. The calculated envelope entropy values for each IMF component are presented in Table 2.

Table 2Computed envelope entropy values

IMF1 | IMF2 | IMF3 | IMF4 | IMF5 |

7.3045 | 7.30464 | 7.30471 | 7.30445 | 7.30451 |

Among these five IMF components, IMF4 has the smallest envelope entropy value, so it is selected as the optimal IMF component. After completing the IMF component selection, we calculate time-frequency domain features including mean and variance of the optimal IMF components as characteristic indicators for feature extraction.

Fig. 8Performance comparison of convergence curves

Using the same methodology as presented in the provided examples, the parameter combinations for these 10 fault types and their corresponding optimal IMF components can be obtained. Detailed data are shown in Table 3.

Table 3Optimal VMD parameters and corresponding IMF components

Condition | Fault Size | Label | Optimal IMF | |

Normal | 0.007 | 1 | (8, 1369) | IMF8 |

IRF | 0.007 | 2 | (5,482) | IMF4 |

IRF | 0.014 | 3 | (7, 3000) | IMF5 |

IRF | 0.021 | 4 | (3, 190) | IMF3 |

REF | 0.007 | 5 | (6, 583) | IMF3 |

REF | 0.014 | 6 | (4, 3000) | IMF3 |

REF | 0.021 | 7 | (8, 158) | IMF5 |

ORF | 0.007 | 8 | (6, 705) | IMF6 |

ORF | 0.014 | 9 | (8, 152) | IMF3 |

ORF | 0.021 | 10 | (4, 1274) | IMF4 |

4.1.4. Fault feature identification

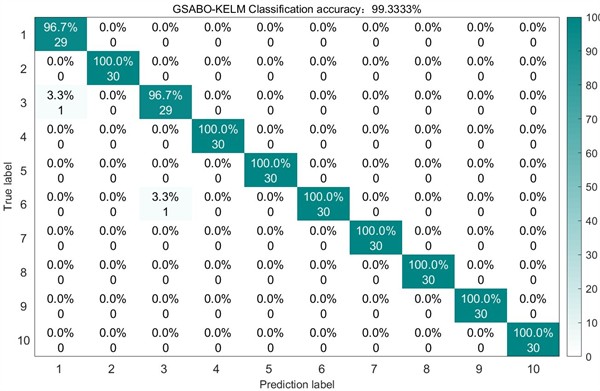

By computing time-frequency domain features of the screened IMF components as characteristic indicators, a fault feature vector matrix is constructed for fault type classification using GSABO-KELM. The samples are fed into KELM, with its kernel parameter and regularization coefficient optimized by GSABO. For the algorithm parameters, the population size is set to 20, the maximum iterations to 30, and the optimization ranges for and are set as [0, 1000] respectively. The optimization process uses classification accuracy as the fitness function. The best parameter set obtained through GSABO-KELM optimization yields an accuracy of 99.3333 %, while Fig. 9 shows the test set confusion matrix using GSABO-VMD decomposition.

Fig. 9Confusion matrix of GSABO on the test set

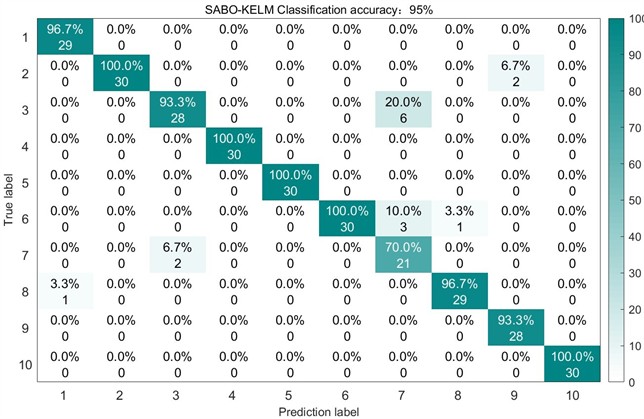

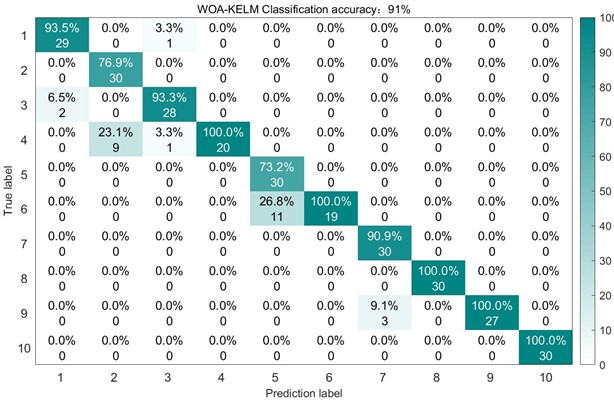

Fig. 10Confusion matrix of SABO on the test set

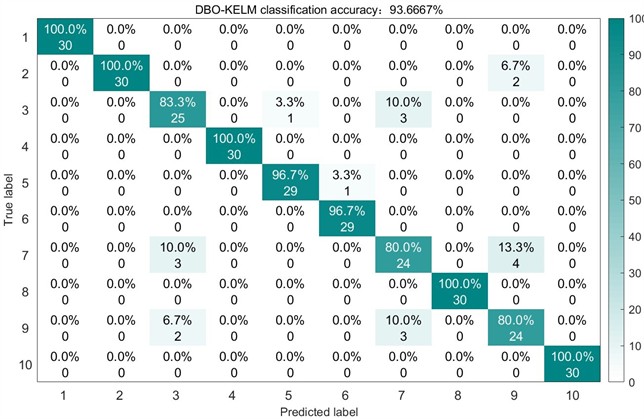

For comparative analysis, we employed the previously benchmarked unoptimized SABO, DBO, and WOA algorithms for VMD decomposition of the experimental dataset. Maintaining identical feature extraction and classification procedures, the test set recognition accuracies achieved were 95 %, 93.6667 %, and 91 % respectively. The corresponding test results and confusion matrices are presented in Fig. 10 through 12.

Following the procedure, the GSABO-VMD-KELM algorithm was compared with existing state-of-the-art methods, introduce accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score as evaluation metrics, the formula is as follows:

where, True Positive (TP): the model predicted a positive case and it was a positive case; False Positive (FP): the model predicted a positive case, but it was a negative case. True Negative (TN): the model predicted a negative case, and it was a negative case. False Negative (FN): the model predicted a negative case, but it was a positive case.

Fig. 11Confusion matrix of DBO on the test set

Fig. 12Confusion matrix of WOA on the test set

The preparation rates of different fault diagnosis models are shown in Table 4, the precision is presented in Table 5, recall rates are presented in Table 6 and the F1 scores are illustrated in Table 7.

In the comprehensive assessment, both GSABO-VMD-KELM and SABO-VMD-KELM exhibited outstanding performance across the four diagnostic metrics. Nevertheless, SABO-VMD-KELM displayed relatively lower accuracy and F1 score in diagnosing the seventh category of faults, indicating a minor limitation. Conversely, Method 1 effectively mitigated the issue of misdiagnosis, demonstrating robust diagnostic capabilities.

Table 4Performance comparison of different algorithms

Number | Algorithm Name | Classification accuracy |

1 | GSABO-VMD-KELM | 99.3333 % |

2 | SABO-VMD-KELM [37] | 95 % |

3 | DBO-VMD-KELM [38] | 93.6667 % |

4 | WOA-VMD-KELM [39] | 91 % |

5 | VMD-ELM [40] | 83.3333 % |

6 | VMD-KELM [41] | 89.6667 % |

7 | VMD-CNN [42] | 87.6667 % |

8 | DCADAN [20] | 90 % |

9 | TTIMN-GCS [21] | 92.3333 % |

10 | AHWCN [22] | 93 % |

Table 5Comparative analysis of (Precision %) across various methodologies

Algorithm Name | Fault labels | |||||||||

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

GSABO-VMD-KELM | 96.7 | 100 | 96.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

SABO-VMD-KELM [37] | 96.7 | 100 | 93.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 70.0 | 96.7 | 93.3 | 100 |

DBO-VMD-KELM [38] | 100 | 100 | 83.3 | 100 | 96.7 | 96.7 | 80 | 100 | 80 | 100 |

WOA-VMD-KELM [39] | 93.5 | 76.9 | 93.3 | 100 | 73.2 | 100 | 90.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

VMD-ELM [40] | 100 | 100 | 86.7 | 100 | 60 | 30 | 83.3 | 100 | 73.3 | 100 |

VMD-KELM [41] | 70 | 96.8 | 85.3 | 100 | 93.8 | 95.2 | 78.9 | 85.3 | 96.6 | 100 |

VMD-CNN [42] | 62.5 | 100 | 77.1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 86.2 | 88.2 | 87.5 | 100 |

DCADAN [20] | 100 | 100 | 86.7 | 100 | 96.7 | 53.3 | 96.7 | 100 | 66.7 | 100 |

TTIMN-GCS [21] | 100 | 100 | 86.7 | 100 | 100 | 80.0 | 90.0 | 100 | 66.7 | 100 |

AHWCN [22] | 82.4 | 93.8 | 83.3 | 100 | 93.8 | 93.1 | 92.0 | 96.7 | 100 | 100 |

Table 6Comparison of (recall%) among different methods.

Algorithm Name | Fault labels | |||||||||

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

GSABO-VMD-KELM | 100 | 100 | 96.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

SABO-VMD-KELM [37] | 100 | 93.8 | 82.4 | 100 | 100 | 88.2 | 91.3 | 96.7 | 100 | 100 |

DBO-VMD-KELM [38] | 100 | 93.8 | 86.2 | 100 | 96.7 | 100 | 77.4 | 100 | 82.8 | 100 |

WOA-VMD-KELM [39] | 96.7 | 100 | 93.3 | 70.0 | 100 | 63.3 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 100 |

VMD-ELM [40] | 60.0 | 100 | 76.5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 89.2 | 66.7 | 85.5 | 100 |

VMD-KELM [41] | 93.3 | 100 | 96.7 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 | 50 | 96.7 | 93.3 | 100 |

VMD-CNN [42] | 100 | 100 | 90.0 | 100 | 96.7 | 36.7 | 83.3 | 100 | 70.0 | 100 |

DCADAN [20] | 71.4 | 100 | 81.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 87.9 | 93.8 | 83.3 | 100 |

TTIMN-GCS [21] | 88.2 | 100 | 83.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 79.4 | 96.8 | 77.0 | 100 |

AHWCN [22] | 93.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90.0 | 76.7 | 96.7 | 73.3 | 100 |

Table 7Comparison of (F1%) of different methods

Algorithm name | Fault labels | |||||||||

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

GSABO-KELM | 98.3 | 100 | 96.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

SABO-KELM [37] | 98.3 | 96.8 | 87.5 | 100 | 100 | 93.7 | 79.2 | 96.7 | 96.5 | 100 |

DBO-KELM [38] | 100 | 96.5 | 84.7 | 100 | 96.7 | 98.3 | 78.7 | 100 | 81.4 | 100 |

WOA-KELM [39] | 95.1 | 87.0 | 93.3 | 82.3 | 84.5 | 100 | 95.2 | 100 | 94.7 | 100 |

VMD-ELM [40] | 75.0 | 100 | 81.3 | 100 | 75.0 | 46.2 | 86.1 | 80.0 | 78.9 | 100 |

VMD-KELM [41] | 80.0 | 98.3 | 90.6 | 100 | 96.8 | 78.4 | 61.2 | 90.6 | 94.9 | 100 |

VMD-CNN [42] | 76.9 | 100 | 83.0 | 100 | 98.3 | 53.7 | 84.7 | 93.7 | 77.8 | 100 |

DCADAN [20] | 83.3 | 100 | 83.9 | 100 | 98.3 | 69.5 | 92.1 | 96.8 | 74.1 | 100 |

TTIMN-GCS [21] | 93.7 | 100 | 85.3 | 100 | 100 | 88.9 | 84.4 | 98.3 | 71.5 | 100 |

AHWCN [22] | 87.5 | 96.8 | 90.9 | 100 | 96.8 | 91.5 | 83.7 | 96.7 | 84.6 | 100 |

4.2. Case 2

4.2.1. Data Collection

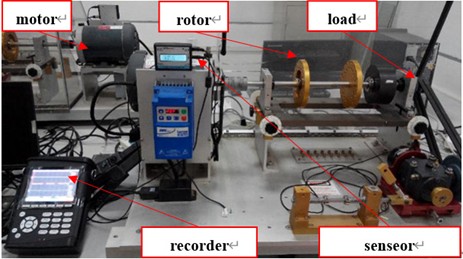

To revalidate the effectiveness of GSABO in rolling bearing diagnosis, verification tests were conducted using the XJTU-SY dataset [43]. The signal acquisition setup is illustrated on Fig. 13. Experiments were performed on a mechanical fault simulator (Spectra Quest Inc.) with seeded faults on NSK 6203 bearings (inner/outer races). Under a constant 1-horsepower load, vibration signals were meticulously collected at three rotational speeds (19.05 Hz, 29.05 Hz, 39.05 Hz) and three fault severity levels (mild, moderate, severe). The test rig comprised three core components: induction motor, rotor assembly, and loading system. A piezoelectric accelerometer (sensitivity: 50 mV/g) acquired motor bearing signals, with data recorded at 25.6 kHz sampling frequency using a CoCo80 data logger.

In this experiment, bearing data with a rotational frequency of 39.05 Hz was utilized, encompassing seven distinct fault conditions: normal operation, mild inner race fault, moderate inner race fault, severe inner race fault, mild outer race fault, moderate outer race fault, and severe outer race fault. Each fault signal contains 2048 sample points, with 120 samples collected per fault category (90 for training, 30 for testing).

Fig. 13XJTU-SY bearing fault diagnosis test rig

4.2.2. Fault signal decomposition

Taking the mild inner race fault as an example, the GSABO was configured with a population size of 15 and maximum iterations of 20 to optimize the decomposition level and penalty factor . Using minimum envelope entropy as the objective function, the optimization yielded . The optimization curve is shown on Fig. 14.

The GSABO achieved convergence in the 2nd generation, outperforming the baseline SABO (6th generation), DBO (4th generation), and WOA (7th generation). This experiment further demonstrates GSABO’s superior convergence characteristics.

The best parameter combinations and the best IMF components for each fault type are shown in Table 8.

Table 8Optimal VMD parameters and corresponding IMF components

Condition | Labels | Optimal IMF | |

Normal | 1 | (10, 517) | IMF6 |

Minor internal ring fault | 2 | (5, 164) | IMF 3 |

Moderate internal ring fault | 3 | (3, 463) | IMF 3 |

Major internal ring fault | 4 | (4, 582) | IMF 2 |

Minor external ring fault | 5 | (8, 630) | IMF 7 |

Moderate external ring fault | 6 | (7, 319) | IMF 7 |

Major external ring fault | 7 | (4, 734) | IMF 4 |

Fig. 14Performance comparison of convergence curves

4.2.3. Fault feature identification

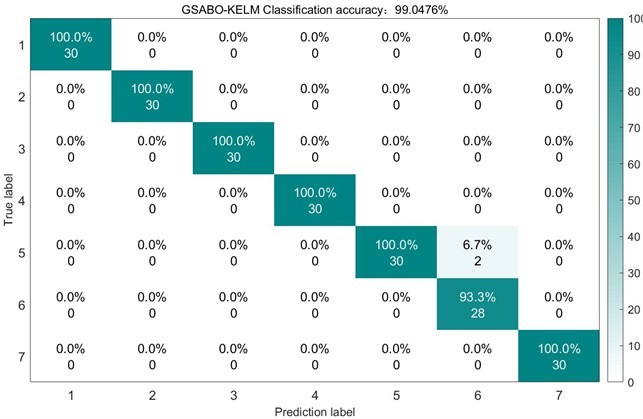

Consistent with the previous experiment, time-frequency domain features of the screened IMF components were computed as characteristic indicators to construct the fault feature vector matrix for GSABO-KELM classification. Using identical optimization parameters, the optimization process uses classification accuracy as the fitness function. The best parameter set obtained through GSABO-KELM optimization yields an accuracy of 99.0476 %, while Fig. 15 displays the test set confusion matrix obtained through GSABO-VMD decomposition.

Fig. 15Confusion matrix of GSABO on the test set

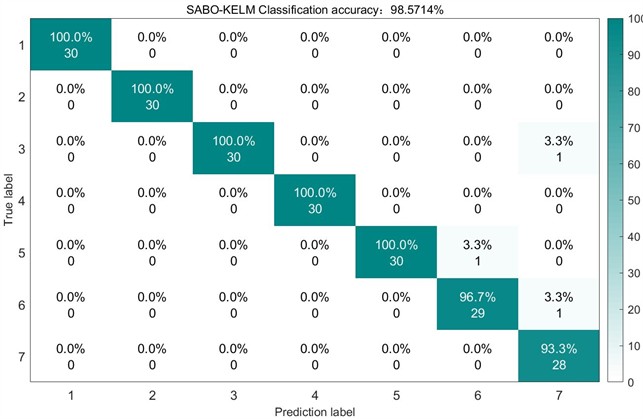

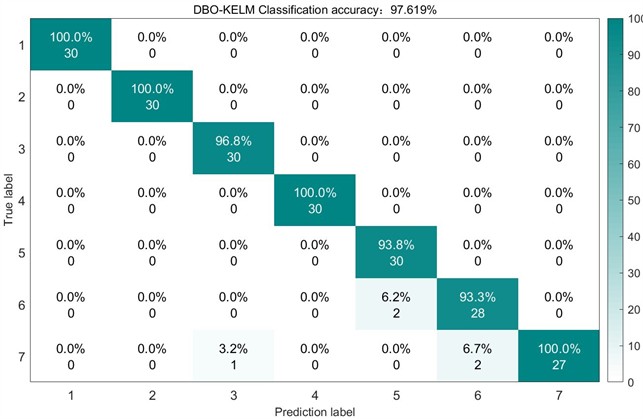

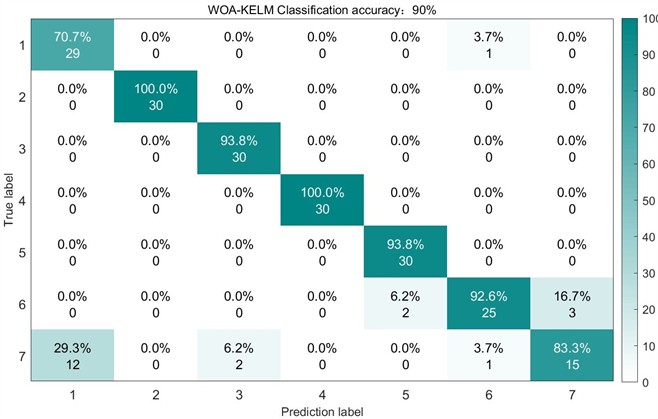

For control experiments, the unoptimized SABO, DBO, and WOA algorithms were employed for VMD decomposition of the sample data while maintaining identical feature extraction and classification procedures. The test set recognition accuracies achieved were 98.5417 % (SABO), 97.619 % (DBO), and 90 % (WOA) respectively. The corresponding test results and confusion matrices are presented in Figs. 16 through 18.

The confusion matrix analysis reveals that GSABO-VMD-KELM misclassified only two Label 6 fault samples as Label 1. Among the four optimization algorithms, GSABO-KELM achieved the fastest diagnostic speed at merely 6.31 seconds 2.35s faster than SABO-KELM (8.66s), 2.67s quicker than DBO-KELM (8.98s), and 4.11s swifter than WOA-KELM (10.42s). The improved SABO algorithm not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also reduces processing time, demonstrating its superior performance in rolling bearing fault diagnosis.

Fig. 16Confusion matrix of SABO on the test set

Fig. 17Confusion matrix of DBO on the test set

5. Conclusions

In this paper, an optimized VMD based on GSABO decomposition of rolling bearing vibration signals is proposed. The IMF component obtained by the decomposition is screened by the envelope entropy, and then the time-frequency domain is calculated as the feature vector for feature extraction.

Fig. 18Confusion matrix of WOA on the test set

Finally, the GSABO optimized nuclear extreme learning machine is input to identify and diagnose the fault types. Through the analysis of experimental data, the following conclusions can be drawn:

1) The GSABO algorithm is employed to optimize the VMD parameters and , eliminating the need for manual or heuristic selection and effectively addressing the challenge of VMD parameter configuration.

2) To enhance the efficiency of the optimization algorithm and address the issue of getting trapped in local optima, a chaotic map and golden sine strategy were integrated to improve the SABO algorithm. Through testing the CEC2005 benchmark functions and comparisons of evolutionary curves, the GSABO algorithm demonstrates certain advantages over the original SABO and other optimization algorithms.

3) The GSABO-optimized KELM is employed to classify the feature vectors extracted from GSABO-VMD decomposition. By comparing the recognition results with those of unimproved SABO, DBO, and WOA optimized KELM and VMD, the advancement of the proposed method is demonstrated. Further validation is conducted using rolling bearing vibration signals from CWRU and XJTU, the accuracy rates reached 99.3333 % and 99.0476 %, respectively, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed method in rolling bearing fault identification. This approach provides valuable insights for research in the field of rolling bearing fault diagnosis.

Although the proposed method demonstrates satisfactory performance in rolling bearing fault diagnosis, certain limitations need to be addressed. The present research is confined to vibration signal analysis, whereas industrial practice involves additional measurable parameters (e.g., temperature, current) that contain critical equipment, health information. Subsequent studies will focus on developing multi-sensor data fusion techniques to deliver more reliable and informative diagnostic solutions for maintenance engineers.

References

-

Q. Li et al., “Fault diagnosis of nuclear power plant sliding bearing-rotor systems using deep convolutional generative adversarial networks,” Nuclear Engineering and Technology, Vol. 56, No. 8, pp. 2958–2973, Aug. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2024.02.056

-

Z. Chen et al., “Research on bearing fault diagnosis based on improved genetic algorithm and BP neural network,” Scientific Reports, Vol. 14, No. 1, p. 15527, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66318-0

-

Z. Wang, D. Shi, Y. Xu, D. Zhen, F. Gu, and A. D. Ball, “Early rolling bearing fault diagnosis in induction motors based on on-rotor sensing vibrations,” Measurement, Vol. 222, p. 113614, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113614

-

Y. Li et al., “Interpretable intelligent fault diagnosis strategy for fixed-wing UAV elevator fault diagnosis based on improved cross entropy loss,” Measurement Science and Technology, Vol. 35, No. 7, p. 076110, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ad3666

-

S. Li, M. Zhao, Y. Wei, S. Ou, D. Chen, and L. Wu, “Adaptive residual spectral amplitude modulation: A new approach for bearing diagnosis under complex interference environments,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 220, p. 111682, Nov. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.111682

-

P. Gao, J. Wang, Z. Shi, W. Ming, and M. Chen, “Long-term temporal attention neural network with adaptive stage division for remaining useful life prediction of rolling bearings,” Reliability Engineering and System Safety, Vol. 251, p. 110218, Nov. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2024.110218

-

Z. Lai, C. Yang, S. Lan, L. Wang, W. Shen, and L. Zhu, “BearingFM: Towards a foundation model for bearing fault diagnosis by domain knowledge and contrastive learning,” International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 275, p. 109319, Sep. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2024.109319

-

B. Cai, L. Zhang, and G. Tang, “Encogram: An autonomous weak transient fault enhancement strategy and its application in bearing fault diagnosis,” Measurement, Vol. 206, p. 112333, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.112333

-

X. Li, Z. Ma, Kang, and X. Li, “Fault diagnosis for rolling bearing based on VMD-FRFT,” Measurement, Vol. 155, p. 107554, Apr. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2020.107554

-

Y. Lei, “Fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on empirical mode decomposition,” Smart Sensors, Measurement and Instrumentation, Vol. 26, pp. 259–292, Apr. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56126-4_10

-

L. Zuo, L. Zhang, Z.-H. Zhang, X.-L. Luo, and Y. Liu, “A spiking neural network-based approach to bearing fault diagnosis,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, Vol. 61, pp. 714–724, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2020.07.003

-

M. Agarwal, “Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition: An adaptive method for noise reduction,” IOSR Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering, Vol. 5, No. 5, pp. 60–65, Jan. 2013, https://doi.org/10.9790/2834-0556065

-

M. Xiao et al., “A new fault feature extraction method of rolling bearings based on the improved self-selection ICEEMDAN-permutation entropy,” ISA Transactions, Vol. 143, pp. 536–547, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2023.09.009

-

Z. Jin, D. He, and Z. Wei, “Intelligent fault diagnosis of train axle box bearing based on parameter optimization VMD and improved DBN,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 110, p. 104713, Apr. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.104713

-

K. Dragomiretskiy and D. Zosso, “Variational mode decomposition,” IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, Vol. 62, No. 3, pp. 531–544, Feb. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1109/tsp.2013.2288675

-

H. Li et al., “Composite fault diagnosis for rolling bearing based on parameter-optimized VMD,” Measurement, Vol. 201, p. 111637, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111637

-

Z. Meng, X. Wang, J. Liu, and F. Fan, “An adaptive spectrum segmentation-based optimized VMD method and its application in rolling bearing fault diagnosis,” Measurement Science and Technology, Vol. 33, No. 12, p. 125107, Dec. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ac8c63

-

K. Yang, G. Wang, Y. Dong, Q. Zhang, and L. Sang, “Early chatter identification based on an optimized variational mode decomposition,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 115, pp. 238–254, Jan. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2018.05.052

-

X.-B. Wang, Z.-X. Yang, and X.-A. Yan, “Novel particle swarm optimization-based variational mode decomposition method for the fault diagnosis of complex rotating machinery,” IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 68–79, Feb. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1109/tmech.2017.2787686

-

X. Wang, H. Jiang, M. Mu, and Y. Dong, “A dynamic collaborative adversarial domain adaptation network for unsupervised rotating machinery fault diagnosis,” Reliability Engineering and System Safety, Vol. 255, p. 110662, Mar. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2024.110662

-

M. Mu, H. Jiang, X. Wang, and Y. Dong, “A task-oriented Theil index-based meta-learning network with gradient calibration strategy for rotating machinery fault diagnosis with limited samples,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, Vol. 62, p. 102870, Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2024.102870

-

T. Zeng, H. Jiang, Y. Liu, and Y. Bai, “AHWCN: An interpretable attention-guided hierarchical wavelet convolutional network for rotating machinery intelligent fault diagnosis,” Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 272, p. 126815, May 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126815

-

M. Amar, I. Gondal, and C. Wilson, “Vibration spectrum imaging: a novel bearing fault classification approach,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, Vol. 62, No. 1, pp. 494–502, Jan. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2014.2327555

-

G. An et al., “Ultra short-term wind power forecasting based on sparrow search algorithm optimization deep extreme learning machine,” Sustainability, Vol. 13, No. 18, p. 10453, Sep. 2021, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810453

-

Y. Jin, H. Wu, J. Zheng, J. Zhang, and Z. Liu, “Power transformer fault diagnosis based on improved BP neural network,” Electronics, Vol. 12, No. 16, p. 3526, Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12163526

-

Q. D. Liu, Y. S. Luo, and J. H. Zhang, “Study on identification method of large wind turbine blade surface crack based on WPT-SVD-KELM,” (in Chinese), Journal of Solar Energy, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp. 155–161, Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.19912/j.0254-0096.tynxb.2021-1258

-

G. B. Huang, H. M. Zhou, X. J. Ding, and R. Zhang, “Extreme learning machine for regression and multiclass classification,” IEEE Transactions on Systems Man and Cybernetics Part B, Vol. 42, No. 2, Apr. 2012, https://doi.org/10/1109/tsmcb.2011.2168604

-

X. H. Zhao, Q. Tan, S. Hu, W. B. Yang, K. X. Xun, and Z. J. Zhang, “Gearbox fault diagnosis based on the LMD cloud model and PSO-KELM,” (in Chinese), Journal of Mechanical Transmission, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 157–163, 2023, https://doi.org/10.16578/j.issn.1004.2539.2023.02.021

-

S. Yang, H. D. Wang, Y. C. Cui, C. Li, and Y. C. Tang, “Bearing fault diagnosis based on parameter optimized VMD with improved ASFA and ELM,” (in Chinese), Modular Machine Tool and Automatic Manufacturing Technique, No. 4, pp. 67–70, Apr. 2023, https://doi.org/10.13462/j.cnki.mmtamt.2023.04.016

-

F. Lu, “A rolling bearing fault diagnosis model based on SABO optimized VMD-WTD-SVM,” (in Chinese), Manufacturing Technology and Machine Tool, No. 7, pp. 32–39, 2024, https://doi.org/10.19287/j.mtmt.1005-2402.2024.07.005

-

J. H. Zhao, N. Luo, and Y. H. Liang, “Research on fault diagnosis of rolling bearing based on ALIF and TMFDE,” (in Chinese), Manufacturing Technology and Machine Tool, No. 7, pp. 9–15, 2024, https://doi.org/10.19287/j.mtmt.1005-2402.2023.07.001

-

P. Trojovský and M. Dehghani, “Subtraction-average-based optimizer: a new swarm-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems,” Biomimetics, Vol. 8, No. 2, p. 149, Apr. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8020149

-

Z. Q. Liu, L. He, L. Yuan, and H. Zhang, “Path planning of mobile robot based on TGWO algorithm,” (in Chinese), Journal of Xi’an Jiao tong University, Vol. 56, No. 10, Oct. 2022, https://doi.org/10.7652/xjtuxb202210005

-

C. H. Liu and Q. He, “Golden sine chimp optimization algorithm integrating multiple strategies,” (in Chinese), Acta Automatica Sinica, Vol. 49, No. 11, Nov. 2023, https://doi.org/10.16383/j.aas.c210313

-

T. Zhang, Y. Q. Chen, Z. Y. Liao, and Y. Chen, “A VMD-MRE bearing fault diagnosis method for northern goshawk parameter optimization,” (in Chinese), mechanical Science and Technology for Aerospace Engineering, 2023, https://doi.org/10.13433/j.cnki.1003-8728.20230226

-

G. J. Tang and X. L. Wang, “Parameter optimized variational mode decomposition method with application to incipient fault diagnosis of rolling bearing,” (in Chinese), Journal of Xi’an Jiao tong University, Vol. 49, No. 5, pp. 73–81, May 2015, https://doi.org/10.7662/xjtuxb201505012

-

Y. He and H. Cui, “Application of SABO-VMD-KELM in fault diagnosis of wind turbines,” Mechanical Engineering Science, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 23–28, May 2024, https://doi.org/10.33142/mes.v5i2.12719

-

Z. Li, X. Li, Z. Huang, B. Lu, S. Li, and D. Xu, “Photovoltaic power generation forecasting using VMD-KELM based on DBO,” in 2024 6th International Conference on Electronics and Communication, Network and Computer Technology (ECNCT), pp. 68–72, Jul. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/ecnct63103.2024.10704395

-

L. S. An, D. S. Sha, and Q. Zhang, “Research on intelligent fault diagnosis of wind turbine based on WOA-KELM algorithm,” (in Chinese), Thermal Power Generation, Vol. 52, No. 12, pp. 131–139, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.19666/j.rlfd.202303091

-

B. An, H. K. Pan, Y. X. Zhang, and X. P. Zhao, “Application of variational mode decomposition in fault diagnosis of automaton,” (in Chinese), China Measurement and Test, Vol. 43, No. 7, pp. 112–116, Jul. 2017, https://doi.org/10.11857/j.issn.1674-5124.2017.07.022

-

G. M. Xie, R. L. Huang, and H. Q. Ding, “Fault diagnosis of transmission lines based on VMD sample entropy and KELM,” (in Chinese), Journal of Electronic Measurement and Instrumentation, Vol. 33, No. 5, pp. 91–95, May 2019, https://doi.org/10.13382/j.jemi.b1801879

-

D. B. Ali, M. E. Mir, H. Reza, and B. E. Mir, “A hybrid fine-tuned VMD and CNN scheme for untrained compound fault diagnosis of rotating machinery with unequal-severity faults,” Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 167, p. 11409, Apr. 2021.

-

S. Liu, J. Chen, S. He, Z. Shi, and Z. Zhou, “Subspace network with shared representation learning for intelligent fault diagnosis of machine under speed transient conditions with few samples,” ISA Transactions, Vol. 128, pp. 531–544, Sep. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2021.10.025

About this article

This work was supported by The Science and Technology Project of Hebei Education Department. (Grant No. CXZX2025039).

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Qing Li: investigation, methodology. Chao Wu: writing-original draft. Qing Lv: supervision. Jin Wang: writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.