Abstract

Fan blades operate in outdoor environments, where the detection of sound signals is susceptible to interference from background noise such as random loads, wind speed, rainwater, and other ambient noise. Therefore, this article proposes an acoustic detection method for wind turbine blade faults based on a dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm-optimized support vector machine. First, the signal is preprocessed using a Butterworth bandpass filter, and the full frequency band is divided into sub-bands using the octave band feature extraction method. Based on frequency domain analysis, the natural frequency offset of the blade is determined. Next, the dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm is applied to optimize support vector machine parameters, while moving average and bandpass filtering are used to smooth the noise power curve and extract impeller speed information. The experimental results show that the proposed method converges in fitness value after 22 iterations, with a detection time of only 6.8 seconds and small fluctuations in impeller speed amplitude. In terms of classification performance, the accuracy of detecting normal samples is 0.95, the recall rate is 0.96, and the F1 score is 0.95. The method demonstrates high prediction accuracy and stability for various types of fault samples and can be reliably applied to the acoustic detection of wind turbine blade faults.

1. Introduction

The fault detection of wind turbine blades is crucial to ensure the reliability and safety of wind power systems. The blade is the key component of wind turbines for harvesting wind energy, and its cost accounts for approximately 20 % of the entire machine. However, owing to its long-term operation in a harsh natural environment, it is subjected to a variety of complex forces, leading to various safety hazards that can easily arise, threatening the safety of the entire system. Therefore, timely and accurate detection of wind turbine blade faults is of great significance [1, 2]. Moreover, deploying these detection methods in actual wind farms also faces many challenges. Wind farms are usually widely distributed and located in complex and diverse geographical environments. The climate conditions, topography, and landforms in different regions vary greatly, posing significant difficulties for the installation, maintenance, and data transmission of detection equipment. At the same time, a large number of wind turbines are installed in wind farms, and real-time, comprehensive monitoring of all wind turbine blades requires substantial manpower, material resources, and financial resources, resulting in high inspection costs. In addition, the electromagnetic environment in actual wind farms is complex, with various interference signals that may compromise the accuracy and reliability of detection signals, increasing the risk of fault misjudgment and missed diagnosis. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a new wind turbine blade fault detection method.

Ciaburro et al. [3] study an axial fan blade ash-accumulation detection method based on acoustic emission recording and deep learning fault diagnosis. Two operational scenarios are considered: no failure and failure. In the fault-free state, the fan blades are completely clean, whereas in the fault state, the deposition of the material is artificially induced. Using a pre-trained network built on the ImageNet dataset (SqueezeNet), the obtained data are used to develop an algorithm based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Transfer learning is applied to spectrogram images extracted from fan acoustic emission records, and highly accurate results (accuracy = 0.95) are obtained under two operating conditions, confirming the effectiveness of the method. However, this method mainly focuses on the specific fault type of ash accumulation on axial flow fan blades, and its applicability for detecting other common faults such as cracking and icing is limited. Moreover, the performance of this method in actual complex background noise environments has not been fully validated, and it may face challenges in accuracy and stability in practical wind farm applications. Ding et al. [4] first summarize existing wind turbine blade detection methods and review the research progress and trends of wind turbine composite blade monitoring based on sound signals. Compared with other blade damage detection technologies, acoustic emission signal detection offers a critical time-advantage by identifying crack initiation and propagation at early stages, while also enabling damage source localization. Aerodynamic noise-based detection technology further enhances this capability, providing not only reliable blade damage monitoring but also practical benefits such as non-intrusive sensor deployment and real-time remote signal acquisition capability. Therefore, this study focuses on the review and analysis of wind turbine blade structural integrity detection and damage source localization technologies based on acoustic signals, as well as the automatic detection and classification of wind turbine blade failure mechanisms combined with machine learning algorithms. In addition to providing a reference for understanding wind turbine health detection methods based on acoustic emission signals and aerodynamic noise signals, this study also points out the development trends and prospects of blade damage detection technology. This has important reference value for the practical application of non-destructive, remote, and real-time monitoring of wind turbine blades. However, there is still room for improvement in signal feature extraction and classification algorithms based on sound signal detection technology. For early weak fault signals, the detection ability is limited, and they are easily affected by background noise interference, leading to misjudgments and missed detections. Moreover, in the presence of multiple types of faults, the detection and classification performance of this technology needs further research. Junxian et al. [5] propose an interpretable integrated selection framework for blade crack detection. First, the depth features extracted by AlexNet and interpretable auxiliary statistical features, combined with an attention weighting mechanism, are used to construct a multi-view-based network. Second, the second-order tensor of the time-frequency image of the acoustic signal is taken as the input of the network, the depth feature of each trained base network is used to determine the region of interest in the activation map using Grad-CAM, and the reliability of the network is calculated by combining the simulation results. Next, diversity selection LIME (DP-LIME) interpretable modules are constructed for embedded auxiliary features, and feature weight distributions are combined to visualize the decision logic in the underlying network. Finally, based on the comprehensive confidence index of each base network, the blade crack-detection results are selectively fused to make a decision. The explainable framework proposed in this study has high precision for blade crack detection, can effectively improve the reliability of the model, and is verified by the actual measurement data of the centrifugal fan. However, this framework has high computational complexity and requires significant hardware resources, which may face cost and efficiency challenges when applied on a large scale in actual wind farms. Moreover, this framework mainly focuses on blade crack detection, and its detection capability for other types of faults has not been fully validated, limiting its universality for comprehensive detection of multiple types of faults. Li et al. [6] propose a low-cost, AI-driven, acoustic-based wind turbine blade health monitoring system framework with higher detection accuracy and signal processing capability in complex sound environments. First, a microphone array is used to capture the blade sounds with rich spatial properties, and a fixed-direction beamforming algorithm is used to integrate the prior spatial information. To further enhance the signal processing and fault detection capabilities, a self-focused transformer model is adopted for feature extraction and fault diagnosis. A practical wind turbine blade health-monitoring system is designed and developed to verify the usability of the proposed framework. The experimental results verify the effectiveness and practicability of the proposed algorithm and provide an effective method for monitoring the health of wind turbine blades. However, the stability and reliability of the system framework in the long-term operation of actual wind farms need further verification. Moreover, the adaptability and generalization ability for wind turbine blades with different models and operating conditions need to be further studied. In addition, the efficiency and performance of the framework in handling large-scale data also need to be further optimized.

The Support Vector Machine (SVM), as one of the most effective machine learning algorithms, has broad application prospects in the field of fault detection. However, in the detection of wind turbine blade faults, its performance largely depends on the selection of parameters. Existing research still has shortcomings in comprehensively considering algorithm complexity, detection efficiency, capability for detecting multiple fault types, adaptability to complex environments in actual wind farms, as well as cost-effectiveness. This study aims to propose an acoustic detection method for wind turbine blade faults based on a dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm-optimized support vector machine, to address the current research gap in this area. In SVM, the choice of kernel function has a significant impact on the performance of the model. For the acoustic detection of wind turbine blade faults, the radial basis function (RBF) kernel has good adaptability due to the complex acoustic signal characteristics and nonlinear relationships. The RBF kernel can map the input space to a high-dimensional feature space, effectively handling nonlinear classification problems, and has fewer parameters, reducing model complexity. Therefore, this study selects the RBF kernel as the kernel function of SVM. Introducing the dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm to optimize the parameters of SVM can further improve its performance in wind turbine blade fault detection. The dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm introduces dynamic Cauchy factors to dynamically adjust the search step size during the bee colony optimization process, improving the exploration capability of the bee colony algorithm and avoiding premature convergence to local optima. The optimization performance of this algorithm has been validated in various benchmark test functions and successfully applied to wind turbine blade fault detection, improving the fault recognition rate. Moreover, this method has strong universality and can be applied to the detection of various types of faults. It has better adaptability and stability in the complex environment of actual wind farms. In addition, by optimizing algorithms and models, it is expected to reduce computational costs and improve cost-effectiveness in practical applications. Therefore, we propose to use a dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm to optimize the acoustic detection of wind turbine blade faults using support vector machines, thereby further improving the accuracy and reliability of acoustic detection of wind turbine blade faults.

2. Feature extraction and frequency domain analysis of fan blade sound signal

2.1. Detection acoustic signal preprocessing

In the initial stage of the wind turbine blade fault acoustic detection system, it is necessary to preprocess the original acoustic signal acquired. The main purpose of this step is to remove noise and interference components from the signal, improve the signal quality, and lay a solid foundation for subsequent feature extraction and frequency-domain analysis. The blades operate in the field for a long time, subject to not only environmental factors such as wind, sand, rain, snow, extreme temperatures, and wind gusts, but also the mechanical forces from the wind turbine. As a result, the collected acoustic signal contains various complex and highly variable strong background noise components, including wind, thunder, rain, and variable pitch noise. When early-stage blade faults occur, the acoustic energy is weak and easily masked by strong background noise. Owing to the limitations of the experimental conditions, the background noise contained in the collected blade acoustic signal is primarily wind noise. Currently, the operational threshold of the wind turbine is generally when the average wind speed exceeds 3.5 m/s, and when the wind speed reaches 12 m/s, the sound pressure level of the wind noise can reach 100 dB. Compared to other background noises, the impact of wind noise is particularly pronounced. Therefore, wind noise must be filtered before extracting the acoustic fault characteristics of the blades.

The spectral energy of wind noise is predominantly concentrated below 200 Hz, whereas fault-induced acoustic signals (e.g., those generated by blade cracking) exhibit a broad frequency range extending to several kHz. Given the rapid attenuation of high-frequency components and the considerable distance between detection microphones and blades, the acquired high-frequency signal energy becomes significantly attenuated in practice, which reduces fault diagnosis reliability. To address this limitation, the present study employed a bandpass filter for preprocessing raw acoustic signals.

To achieve the flattest possible frequency response curve in the wind turbine blade’s passband, a Butterworth bandpass filter is selected in this study, and the blade’s square amplitude-frequency response function is as follows:

Among them:

where represents the filter order [7], denotes the 3 dB cutoff frequency, specifies the upper cutoff frequency, and indicates the lower cutoff frequency of the fan blade filter. Higher values of yield flatter passband characteristics and narrower transition bands, resulting in improved filtering performance at the cost of increased computational complexity.

Considering the computational efficiency and real-time processing requirements, the filter order is set to 30-50. To balance between excluding excessive noise (caused by an overly wide passband) and preserving useful signals (which might be filtered out with an excessively narrow passband), the lower cutoff frequency is selected as 50-200 Hz and the upper cutoff frequency as 10-15 kHz.

2.2. Feature extraction of fan blade sound signal

After preprocessing the acoustic signal, feature extraction is performed. This key step in wind turbine blade fault identification involves extracting signal characteristics that reflect blade operational status. Since wind turbines require minimum wind speeds to generate power, blade rotation inevitably occurs with higher wind speeds and consequently greater wind noise. The acquired acoustic signals additionally contain natural background noise and mechanical noise from yaw operations or cooling duct operation. Analysis of field-recorded signals reveals that blade-sweeping wind noise has the most significant impact on fault acoustic signals compared to other noise sources, being both persistent and high-intensity. Given that wind noise primarily occupies the low-frequency band while fault-induced acoustic signals demonstrate broad spectral distributions, this study utilizes a Butterworth bandpass filter for preprocessing. This method effectively suppresses low-frequency wind noise while retaining essential fault features, achieving preliminary audio denoising. Importantly, acoustic signal analysis typically focuses on macroscopic energy distribution patterns rather than precise frequency-point energy measurements.

The human audible frequency range can be systematically divided into sub-bands according to psychoacoustic principles, typically maintaining a constant ratio between upper and lower cutoff frequencies. Within each sub-band, the sound energy is considered uniformly distributed, allowing comprehensive analysis of spectral energy distribution across all frequency ranges [8]. Octave-based signal feature energy extraction involves two main processing stages:

1) The full frequency band of the fan blade is divided into several subbands.

Where , , and represent the upper cutoff, lower cutoff, and center frequencies of each sub-band, respectively. Their relationships are defined as:

When = 1, the division is termed an octave [9]; when = 1/3, it becomes a 1/3 octave. The parameter must be properly selected according to specific analysis requirements. For higher frequency resolution that necessitates narrower sub-bands, should be set to smaller values.

2) The acoustic energy within each fan blade frequency band is computed.

Let denote the energy of the -th frequency band and represent the spectral amplitude of the acoustic signal. The sub-band acoustic energy is calculated as:

This energy is then converted to sound pressure level using the following transformation:

where is the reference sound pressure (typically 2×10−5 Pa in atmospheric conditions) [10], and represents the sound pressure level for the corresponding fan blade frequency band.

2.3. Frequency domain analysis of fan blade signal

Based on the extracted features, frequency domain analysis is performed on the wind turbine blade's acoustic signal. This analysis reveals the signal’s spectral distribution characteristics and facilitates identification of frequency variations induced by blade faults. As a primary approach for vibration signal analysis, frequency domain analysis examines the blade signal’s frequency spectrum through Fourier transform to obtain its amplitude and phase spectra. The method extracts the signal’s frequency components, reflecting the vibration signal’s intrinsic frequency structure through each wind turbine component’s natural frequency. According to theoretical mechanics principles, the wind turbine blade constitutes a single-degree-of-freedom first-order elastic system, with its first-order natural frequency calculated as shown in Eq. (6):

where represents the wind turbine blade stiffness coefficient, which is determined by the material properties at a specific location [11]. denotes the mass at that location, and represents the constant of PI, the value is 3.14. This relationship demonstrates that when the local stiffness is high and the mass is low, the natural frequency increases; conversely, with lower stiffness and higher mass, the natural frequency decreases. Modal analysis of the wind turbine blades reveals that their vibration natural frequency ranges from 0.3 Hz to 1.2 Hz.

This study proposes a frequency-domain methodology for analyzing blade natural frequency migration, consisting of two components: (1) comparative analysis of natural frequencies among three blades within the same unit during identical operational periods, and (2) temporal comparison of natural frequency variations for individual blades across different operational periods within the same unit. The three-blade comparative analysis procedure is implemented as follows. First, the Fourier transform (FFT) method is employed to extract the first-order natural frequencies of the blades from the blade pendulum data during a specific period, denoted as . Second, the blade’s natural frequency factory value N corresponding to its serial number is obtained from the blade factory report. Finally, the relationship between and is compared to evaluate the blade’s natural frequency variation [12].

When ice accumulates on the blade, the blade mass increases. According to the first-order natural frequency formula , when the blade stiffness coefficient remains constant, . Conversely, when the blade stiffness coefficient decreases due to blade cracking, the first-order natural frequency formula shows that for constant blade mass, .

The comparative analysis method for evaluating natural frequency variations of the same blade across different operational periods involves the following steps. The blade oscillation arrays are defined as and , where represents earlier time data than . First, the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) method is applied to extract the first-order natural frequencies and from the oscillation data . Second, the relationship between and is analyzed to assess blade natural frequency changes. When corresponds to normal operation (pre-icing) and to post-icing conditions, the increased blade mass yields according to the first-order natural frequency formula . Conversely, when represents normal operation (pre-cracking) and post-cracking conditions, the reduced stiffness coefficient results in . For cross-unit comparison within the same wind field, natural frequencies are normalized to dimensionless frequency coefficients using Eq. (7):

where represents the dimensionless natural frequency coefficient of the blade [13], denotes the natural frequency extracted from real-time blade oscillation data, and corresponds to the nominal natural frequency value from the blade manufacturer's factory report for the specified blade designation.

3. Implementation of fan blade fault acoustic detection based on dynamic Cauchy swarm algorithm to optimize support vector machine

3.1. Dynamic Cauchy swarm algorithm is used to optimize parameters of support vector machine

Following acoustic signal processing and analysis, the dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm (DCABC) is employed to optimize support vector machine (SVM) parameters. As a powerful classification tool, SVM plays a crucial role in wind turbine blade fault detection, though its performance significantly depends on parameter selection. The DCABC algorithm identifies optimal SVM parameter combinations within the search space to enhance fault detection accuracy and efficiency. This algorithm simulates actual bee foraging behavior through three distinct roles: employed bees, onlooker bees, and scout bees. During initialization, the number of food sources equals the colony size, with each source’s location representing a potential solution. The algorithm first randomly generates an initial population, then conducts local searches around the top 50 % individuals with superior fitness values through competitive selection. Subsequently, onlooker bees employ a roulette wheel selection strategy to identify promising solutions for intensive neighborhood searches, generating the remaining population members. Finally, scout bees explore new regions when existing food sources are abandoned. The total number of food sources is denoted as . The initial positions randomly generated within the blade's solution space is expressed as:

where is the upper boundary of the fan-blade colony search range [14]; is the lower boundary of the search range of a bee colony on a fan blade; is a random number between 0 and 1.

According to Eq. (9), the employed bees randomly select food sources for crossover search, update the food source positions, and generate new candidate solutions. The fitness value of each new solution is evaluated using the greedy criterion to determine whether it replaces the current optimal solution for wind turbine blade fault detection:

where , , and ; are random numbers between [–1, 1].

The onlooker bee selects a food source for exploitation based on probability through roulette wheel selection [15], computes the corresponding fitness value from its neighborhood search using Eq. (10), and applies the greedy criterion to determine whether to accept the new solution as the optimal solution for wind turbine blade fault detection:

where is the fan blade moderation function value of :

where represents the objective function value of the -th solution for the fan blade [16]; is the reference absolute value.

If the nectar source remains unchanged after a predetermined number of limit searches, it is abandoned. The corresponding employed bee transitions to a scout bee and randomly generates a new nectar source according to Eq. (11) to replace the original solution for subsequent iterations.

Due to the stochastic nature of search step size determination, conventional onlooker bee neighborhood searches around selected food sources may fail to ensure sufficient global exploration during initial phases while potentially converging to local optima in later stages. To address this limitation, the proposed swarm optimization algorithm dynamically adjusts search ranges by: (1) expanding exploration scope during initial iterations, and (2) progressively intensifying search near identified promising solutions. Although linear adjustment of step size reduces randomness, it may induce premature convergence. This study introduces a dynamic factor to modify the wind turbine blade objective function as follows:

where denotes the minimum inertia weight of the fan blade [17]; is the maximum inertial weight of the fan blade; denotes the fitness value of the fan blade solution, and the position update formula for leader and follower bees is given by:

As shown in Eq. (14), during the initial phase when iteration count is small, the dynamic weighting factor remains large. This expanded dynamic factor widens the colony’s search range, enabling the algorithm to escape local optima while maintaining solution diversity and preventing oversight of global optima. In later search stages when increases, the reduced value enhances employed bees’ local search capability near promising solutions, thereby improving the algorithm’s dynamic search performance.

When the number of employed bees exploiting a given food source reaches the abandonment limit, these bees transition to scout bees and generate new solutions through random exploration. To enhance the algorithm's perturbation capability beyond this inherent randomness, this study incorporates the Cauchy distribution into the scout bees’ search mechanism. This modification strengthens the algorithm's ability to escape local optima. The Cauchy probability density function for the wind turbine blade optimization is defined as follows:

Eq. (15) demonstrates that when 1, follows the standard Cauchy distribution Cauchy(0,1). The corresponding function generated by this Cauchy random variable is , where represents a uniformly distributed random variable in the interval [0, 1] [18].

The fan blade search formula for scout bees is defined as:

The parameter optimization procedure for the support vector machine using the dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm (DCABC) is implemented through the following steps:

(1) Algorithm Initialization: Set the abandonment limit lim and maximum iterations . Since both the penalty parameter and kernel parameter require optimization, the solution dimension 2. Randomly generate initial solutions, encode and values into the SVM model, evaluate classification accuracy on wind turbine blade training samples to determine fitness values using DCABC, and record these initial solutions with their corresponding fitness values.

(2) Employed Bee Phase: Employ Eq. (14) for guided random search of new food sources. If a new solution's fitness surpasses the current solution's fitness, update the solution; otherwise, retain the current solution.

(3) Probability Calculation: Compute selection probabilities for all solutions using Eq. (10).

(4) Onlooker Bee Phase: Onlooker bees select solutions via roulette wheel selection based on probabilities, perform neighborhood searches using Eq. (14), and evaluate fitness. Update the global best solution if improved solutions are found.

(5) Scout Bee Phase: If a solution's fitness shows no improvement after lim iterations, the employed bee becomes a scout bee to discover new solutions via Eq. (16).

(6) Solution Recording: Store the current optimal solution after each iteration.

(7) Termination Check: If reaching maximum iterations or satisfying error thresholds, output the optimal solution; otherwise, repeat from Step (2).

3.2. Evaluation of impeller speed

Following the determination of optimal SVM parameters, the impeller speed is evaluated as a critical operational parameter for wind turbine performance assessment and blade condition monitoring. The speed calculation employs a smoothing algorithm comprising three stages: (1) selection of a frequency band containing pure blade acoustic signatures, followed by frequency-axis normalization of the summed noise to derive a one-dimensional noise power array; (2) application of moving average and bandpass filtering to smooth the noise power curve, where the moving average eliminates high-frequency fluctuations while preserving long-term trends; (3) implementation of the computational process as follows:

where denotes the moving average of the fan impeller, computed as the arithmetic mean of data subsets with length equal to 1/4 of the minimum rotation period along the time axis, represents the arithmetic mean length of the fan blade [19], corresponds to the bandpass-filtered smooth noise power spectrum of the fan impeller, and are the discrete Fourier transform and its inverse respectively, extracts the real component of the fan impeller input signal, and is a composite bandpass filter combining low-pass and high-pass filters:

where and represent the low-pass and high-pass filters for the fan impeller, respectively; denotes the length of the fan impeller's equal-duration signal; is the acoustic sampling frequency; and correspond to the maximum and minimum rotational speeds of the fan [20]. The speed-related frequency band was isolated through bandpass filtering, effectively suppressing non-speed components in the frequency domain to stabilize the noise power signal. The impeller speed was subsequently determined by calculating three times the reciprocal of the time interval between local minima in the processed signal:

where denotes the -th minimum time point and represents the -th impeller speed recorded on the fan’s time axis.

A local minimum is identified when a value satisfies the condition:

where, corresponds to the local minimum value of the impeller signal, and are the adjacent signal values preceding and following the minimum, respectively.

3.3. Implementation of fault acoustic detection

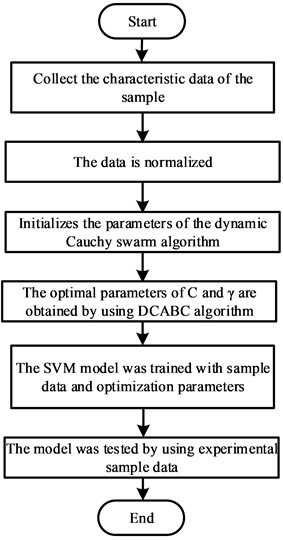

The impeller speed evaluation significantly enhances the reliability of acoustic fault detection. The wind turbine blade fault detection methodology comprises: (1) acoustic signal acquisition and feature extraction, (2) data normalization, (3) DCABC algorithm initialization, (4) optimization of SVM parameters ( and ) via DCABC, (5) SVM model training with optimized parameters, and (6) fault detection using experimental datasets. The complete workflow is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1Flow chart of fault acoustic detection.

This completes the acoustic fault detection system design for wind turbine blades, implementing a dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm-optimized support vector machine methodology.

4. Experimental results and analysis

4.1. Preparation for experiment

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed wind turbine blade fault acoustic detection method using dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm-optimized support vector machine, the designed approach is compared with methods reported in references [3]-[6].

Acoustic signals are acquired from ground-based measurements of wind turbine operation within the rotational speed range of 7-17 r/min. Below this range, power generation ceases, while speeds exceeding this range trigger protective blade stoppage. Each 10-second sample is designed to capture at least three blade-passing events (one complete rotation cycle). The tested wind turbines (model: UP1500-82) have a rated capacity of 1.5 MW. The acquisition system comprises a YG-201 microphone, MPS-140801 data acquisition card, and LabVIEW-equipped laptop computer.

The experiment collects 1,000 acoustic signal samples encompassing four distinct fault conditions (normal operation, leading-edge cracks, trailing-edge cracks, and surface cracks), with 250 samples per category. The dataset is partitioned into training (70 %, 700 samples) and testing (30 %, 300 samples) subsets. To ensure result reliability, 5-fold cross-validation is implemented on the training set-each iteration utilizes 4 subsets (560 samples) for model training and the remaining subset (140 samples) for validation, with this process repeated until all subsets served as the validation set once.

The experimental configuration comprises 16.0 GB RAM with PyCharm 2021.2.4 as the development environment. The computational procedure executes 8,000 operational steps with a sampling frequency range of 0-2,000 Hz.

The experimental setup configuration is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2Experimental environment diagram

The study analyzes acoustic detection data from six wind turbine blades (representative samples selected from the aforementioned 1,000-sample dataset). The original dataset comprises wind speed, wind direction, temperature, voltage, current, active power, and impeller rotational speed for model training. Representative sample data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1Experimental parameters

Name | Argument |

Wind speed | 5.2 m/s |

Wind direction | North by east 30 degrees |

Temperature | 25.0 degrees Celsius |

voltage | 220 volts |

Electric current | 10.0 amperes |

Active power | 2200 watts |

Impeller speed | 12 RPM |

4.2. Experimental results

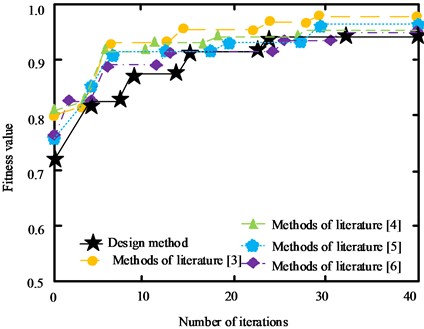

To validate the algorithm’s effectiveness, a comparative analysis of fitness values is conducted between the proposed method and existing approaches, with results illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 demonstrates that the proposed method achieves convergence at 22 iterations, compared to 30 iterations for conventional approaches. This accelerated convergence results from synergistic enhancements combining the dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm’s efficient search strategy with optimized SVM parameters, collectively improving both detection performance and computational efficiency. These advantages significantly enhance the method's practical value for wind turbine blade fault acoustic detection.

A comparative analysis of fault detection times between the proposed algorithm and existing methods is presented in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, for all fault types (normal, leading-edge cracking, trailing-edge cracking, and skin cracking), the detection time of the proposed method is generally shorter than that of the other methods. For instance, under normal conditions, the detection time of the proposed method is 6.8 seconds, whereas the method in [3] requires 11.9 seconds, and the method in [4] takes 11.5 seconds. This demonstrates that the proposed method has a significant advantage in detection efficiency. The improvement is attributed to the dynamic Cauchy swarm algorithm, which efficiently identifies the optimal support vector machine (SVM) parameters through its high-performance search strategy and dynamic adjustment capability. This optimization not only enhances the SVM’s classification accuracy but also reduces the model’s training and prediction time.

Fig. 3Comparison curves of fitness values of different methods

Table 2Comparison results of fault detection time for different methods/s

Type | Design method | Methods of literature [3] | Methods of literature [4] | Methods of literature [5] | Methods of literature [6] |

Normal | 6.8 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 10.6 | 10.7 |

Leading edge cracking | 2.4 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 7.6 |

Trailing edge cracking | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.7 |

Skin cracking | 0.3 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

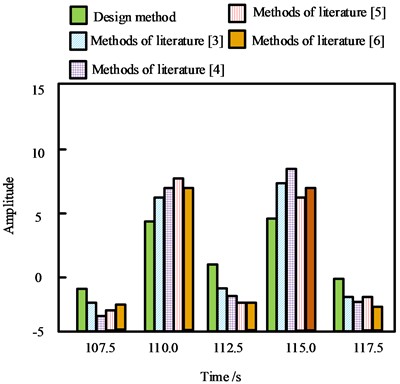

To further demonstrate the advantages of the proposed method, the impeller speed is analyzed, and the vibration amplitudes of different methods are compared. The results are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4Evaluation results of impeller speed with different methods

As evident from Fig. 4, the impeller speed amplitude of the conventional method exhibits significant fluctuations, failing to satisfy the requirements for acoustic detection of fan blade faults. In contrast, the proposed method demonstrates smoother impeller speed amplitude with reduced fluctuations. This improvement stems from the method's enhanced classification performance, robustness, and fault feature extraction capability for SVM, along with its ability to maintain stable impeller speed control. These advantages ensure greater stability and reliability in acoustic detection of fan blade faults.

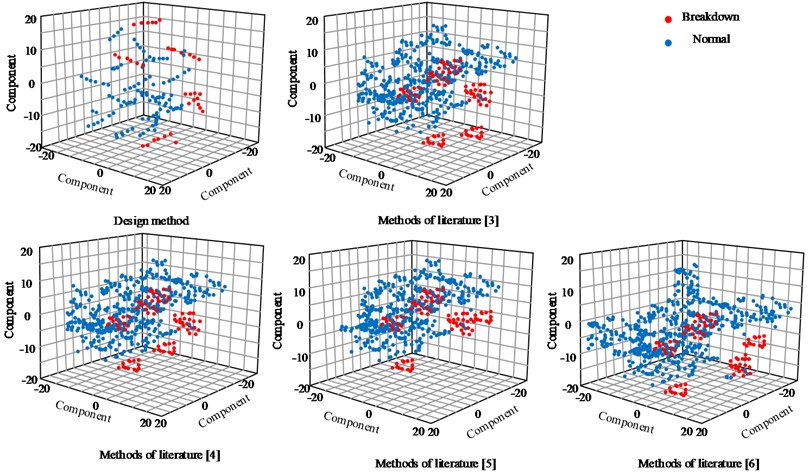

The acoustic detection results for fan blade faults obtained by the proposed and conventional methods are compared in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5Comparison of fault acoustic detection results of different methods.

Fig. 5 clearly illustrates distinct three-dimensional distribution patterns between fault and normal samples. The overlapping ranges between both sample types indicate similarities in blade operating conditions across different states, demonstrating that relying exclusively on environmental variables or operational parameters is insufficient for accurate ice detection on wind turbine blades. In the conventional method, the two sample types exhibit cross-distribution patterns with overlapping data groups, revealing significant coupling between normal and faulty samples. This suggests redundant characteristics in the original data that introduce noise into the sample set. In contrast, the proposed method forms well-separated clusters in the feature space, preserving raw data historicity while effectively suppressing noise interference from the original dataset. In summary, the SVM-optimized acoustic detection method incorporating the dynamic Cauchy bee colony algorithm demonstrates significant advantages, including enhanced SVM classification capability, improved optimization through the dynamic Cauchy algorithm, reduced noise effects, and higher recognition rates. These advantages indicate strong potential for wind turbine blade fault detection applications.

4.3. Classification performance evaluation

To thoroughly assess the classification performance of the proposed method, evaluation metrics including the confusion matrix, accuracy, recall rate, and F1-score are computed. The confusion matrix provides visual representation of the model's predictions for each category, whereas accuracy, recall, and F1 score quantitatively measure the model's performance from different aspects.

(1) Confusion matrix.

The confusion matrix of the proposed method on the test set is presented in Table 3. The results demonstrate accurate predictions for both normal samples and various fault types (leading-edge cracking, trailing-edge cracking, and skin cracking), with minimal misclassification cases observed.

Table 3Prediction results of the model for normal samples and various types of fault samples

Real category/predicted category | Normal | Leading edge cracking | Rear edge cracking | Skin cracking |

Normal | 210 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

Leading edge cracking | 8 | 195 | 7 | 5 |

Rear edge cracking | 2 | 6 | 205 | 7 |

Skin cracking | 1 | 4 | 5 | 210 |

(2) Accuracy, recall, and F1-score.

Based on the confusion matrix analysis, the accuracy, recall, and F1-score for each category are calculated, with the results presented in Table 4.

Table 4Accuracy, recall, and F1-score

Category | Accuracy | Accuracy | F1-score |

normal | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.95 |

Leading edge cracking | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

Rear edge cracking | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

Skin cracking | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

The data in Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the excellent classification performance of the proposed method. the confusion matrix reveals accurate predictions across all sample types with minimal false positives: 210 normal samples are correctly classified, with only 5, 3, and 2 misclassified as other faults; 195 leading-edge cracking samples are accurately identified, with a maximum of 8 misclassifications; while trailing-edge cracking and skin cracking samples achieve 205 and 210 correct predictions respectively, with similarly low misclassification rates. Quantitative metrics further confirm this performance, with normal samples achieving 0.95 accuracy, 0.96 recall, and 0.95 F1-score. Leading-edge cracking samples show 0.92 accuracy, 0.89 recall, and 0.91 F1-score, while trailing-edge cracking and skin cracking samples maintain high metric values between 0.93-0.96. These results indicate that the proposed method delivers outstanding classification performance, demonstrating both high accuracy and stability for normal and all fault sample types, confirming its reliability for practical classification tasks.

5. Conclusions

The acoustic detection of fan blade faults is enhanced through integration of a dynamic Cauchy swarm algorithm with support vector machine (SVM). Low-frequency wind noise is effectively eliminated by precise optimization of the filter’s order and cutoff frequencies (both lower and upper bounds), combined with sub-band acoustic energy computation. The algorithm’s performance is improved through dynamic parameters that automatically regulate the search step size: initially broadening the search range to avoid missing optimal solutions, then narrowing the search scope to enhance local search precision. Although the dynamic Cauchy swarm algorithm boosts SVM performance, its computational intensity and extended processing time present practical constraints for real-time diagnostics. To mitigate this, computational optimizations are implemented to accelerate processing while maintaining algorithmic effectiveness. Parallel research explores more efficient SVM parameter optimization techniques to improve fault identification rates. Furthermore, multisensor data fusion is employed to combine complementary measurements (including vibration, temperature, and pressure) for comprehensive fan blade condition monitoring, thereby increasing detection reliability and accuracy.

References

-

F. Liu, K. Wei, Y. Yin, and Y. Ma, “Experimental study on fault diagnosis of wind turbine blades based on acoustics,” in Mechanisms and Machine Science, pp. 110–120, Sep. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-70235-8_11

-

C. He, B. Liu, Z. Jiang, and W. Huang, “Acoustic pulse extraction of fan blades based on energy threshold optimization,” in 4th International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Science (EIECS), pp. 1–7, Sep. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/eiecs63941.2024.10800507

-

G. Ciaburro, S. Padmanabhan, Y. Maleh, and V. Puyana-Romero, “Fan fault diagnosis using acoustic emission and deep learning methods,” in Informatics, Vol. 10, No. 1, p. 24, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics10010024

-

S. Ding, C. Yang, and S. Zhang, “Acoustic-signal-based damage detection of wind turbine blades-a review,” Sensors, Vol. 23, No. 11, p. 4987, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/s23114987

-

J. Shen, T. Ma, and D. Song, “Crack damage detection of centrifugal fan blades based on interpretable ensemble selection framework,” (in Chinese), Journal of Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 60, No. 12, pp. 183–193, 2024.

-

Z. Li, Y. Zhao, Y. Zhang, X. Li, and L. Bu, “A novel transformer-enhanced and acoustic-based approach for wind turbine blade fault detection with integrated system implementation,” Journal of Engineering Design, Vol. 36, No. 5-6, pp. 642–671, Jun. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1080/09544828.2024.2332122

-

T. Ma, J. Shen, D. Song, and F. Xu, “A vibro-acoustic signals hybrid fusion model for blade crack detection,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 204, p. 110815, Dec. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.110815

-

J. Shen, D. Song, T. Ma, and F. Xu, “Blade crack detection based on domain adaptation and autoencoder of multidimensional vibro-acoustic feature fusion,” Structural Health Monitoring, Vol. 22, No. 5, pp. 3498–3513, Feb. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217221139134

-

Y. Zhang, M. Radzieński, S. Xue, Z. Wang, and W. Ostachowicz, “A method for detecting cracks on the trailing edge of wind turbine blades based on aeroacoustic noise analysis,” Structural Health Monitoring, Dec. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217241303452

-

S. Wei et al., “Prediction of wind turbine faults shutdown occurring time based on EMD-LSTM,” (in Chinese), Computer Simulation, Vol. 40, No. 12, pp. 113–118, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9348.2023.12.020

-

L. Tieghi, S. Becker, A. Corsini, G. Delibra, S. Schoder, and F. Czwielong, “Machine-learning clustering methods applied to detection of noise sources in low-speed axial fan,” Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, Vol. 145, No. 3, Mar. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4055417

-

J. Zhang, Y. Chen, N. Li, J. Zhai, Q. Han, and Z. Hou, “A weak fault identification method of micro-turbine blade based on sound pressure signal with LSTM networks,” Aerospace Science and Technology, Vol. 136, p. 108226, May 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2023.108226

-

A. N. V. Rao, T. N. Satish, V. P. S. Naidu, and S. Jana, “Machine learning augmented multi-sensor data fusion to detect aero engine fan rotor blade flutter,” International Journal of Turbo and Jet-Engines, Vol. 40, No. s1, pp. s485–s506, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1515/tjj-2022-0066

-

S. Zhang et al., “UAV based defect detection and fault diagnosis for static and rotating wind turbine blade: a review,” Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 1691–1729, Apr. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1080/10589759.2024.2395363

-

M.-L. Lee, Y.-H. Sun, Y.-C. Chi, Y.-A. Chen, Y.-L. Tsai, and Y.-C. Tseng, “Acoustic camera-based anomaly detection for wind turbines,” in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP), pp. 344–349, Jun. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1109/smartcomp61445.2024.00079

-

S. Sun, T. Wang, and F. Chu, “Review of structural health monitoring of wind turbine blades based on vibration and acoustic measurement,” (in Chinese), Journal of Mechanical Engineering, Vol. 60, No. 7, pp. 79–92, 2024.

-

Y. Zheng, Q. Gao, and H. Yang, “Non-synchronous blade vibration analysis of a transonic fan,” Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 178–190, Jan. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2022.04.011

-

S. Paudel, S. Niroula, S. Bhattarai, P. Sapkota, and S. Chitrakar, “Vibrational analysis on cooling fan with induced mechanical faults,” in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 1385, No. 1, p. 012011, Aug. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1385/1/012011

-

H. Li and Z. Wang, “Anomaly identification of wind turbine blades based on mel-spectrogram difference feature of aerodynamic noise,” Measurement, Vol. 240, p. 115428, Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115428

-

D. Song, J. Shen, T. Ma, and F. Xu, “Multi-objective acoustic sensor placement optimization for crack detection of compressor blade based on reinforcement learning,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, Vol. 197, p. 110350, Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.110350

About this article

The authors have not disclosed any funding.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

WangChun Yang: writing-original draft preparation. Shuanghui Chen: writing-review and editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.